What a bittersweet little sojourn down memory lane it was, reaching into one of those nasty free boxes from which the Village Voice is dispensed these days to pick up a copy of the paper’s 50th-anniversary issue. A big, fat thing it was, too, the big five-oh, sporting a reproduction of a Voice cover from each year of its existence, 1955 on to now. There were reprints of old stories, rekindlings of famous, long-vanished bylines. Up front was Mailer’s, of course, the founding editor lambasting the paper’s nonexistent copy department for so many “obvious mis-spellings,” meaning alterations in his essay “The Hip and the Square,” and saying that he had no choice, given “the fairly sharp words—certain things said which can hardly be unsaid,” but to resign his column.

Other hallowed names were invoked: Jane Jacobs, who stopped Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, thereby making Soho safe for Prada, and Jack Newfield, who sent crooked judges and landlords to jail, ten at a time. Noted too were Jonas Mekas, Andrew Sarris (how much us budding Queens auteur theorists owed him!), the beatnik John Wilcock, Howard Smith, jill johnston (only lowercase for her), Lucian Truscott IV, Alexander Cockburn, Ellen Willis, and dozens more, with pictures by Fred McDarrah and cartoons by Feiffer, one more dance to the newsprint fungibility of it all.

The Voice: How to explain what it meant, in 1961, to plunk down a dime onto the counter of Union newsstand on 188th Street and thumb through those mucky little pages—pages that opened a Cocteau-like portal to a whole other world. Here was the ticket from Mom’s pot roast, from civil service and the neat six-foot square of lawn in front of the corner house on 53rd Avenue. Simply to be seen with the Voice set you apart: You were one of those people—hair too long, mouth too smart, not likely to go to the prom. Growing up in Flushing, the dream felt good.

Later on, as a freshman at the University of Wisconsin, I had a subscription. The guys in the hall, all aggie majors and barely closeted Jew-haters (I assumed), looked at the picture of LeRoi Jones on the cover and asked, “What’s this, a commie paper?” No, I tried to explain to these sons of McCarthy, it wasn’t a commie paper, it had a lot of stuff in it: politics, jazz, stuff about movies. I tried to tell them I read the paper because I was from New York and to me the Voice embodied the legitimate, indigenous clarion of what mattered. Really, I read it because I was homesick and the Voice was my lifeline; it kept me sane, and warm, in the middle of goddamn Wisconsin, where the temperature hadn’t broken zero in weeks.

My dorm mates looked over the paper again. There were some naked hippies in there, I think, maybe a Newfield piece about some judge who took money. “This is a commie paper,” they said again. “Yeah, right, it’s a commie paper, you farmers,” I said, slamming the dorm-room door. The Voice: It was an attitude, back then.

This, and the fact that I would wind up writing for the paper during the seventies and eighties, made the 50th-anniversary issue a perfect nostalgia storm: Like, wow, look at that picture of Dustin Hoffman, I forgot he lived right next to that townhouse on 11th Street the Weather Underground bombers blew up. What a long, strange proverbial trip.

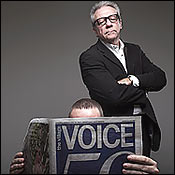

That was my frame of mind as I slipped past security at the current Voice office at 36 Cooper Square. I wanted to be there because it figured to be a special day, one that could only be conjured by the lords of irony that often hover over the Village Voice. On this day, the same one that the 50th-anniversary issue hit the streets, the Voice management thought it would be an excellent idea to have the paper’s new owner come by for the very first time. And there he was, blown in from the Barry Goldwater–whelped precincts of Phoenix, Arizona, no less, one Mr. Michael Lacey, a tallish 57-year-old with spiky gray hair, watery pale-blue eyes, and spreading shanty-Irish honker.

In the 50th, there is a piece by Jarrett Murphy tracking the checkered history of Voice ownership. They are all in there, from Dan Wolf and Ed Fancher, who along with Mailer spent $10,000 to open the paper in a second-floor office at 22 Greenwich Avenue. Wolf sold it to Kennedy pal Carter Burden, who sold it to Clay Felker, the founder of New York Magazine. Felker (one afternoon a disgruntled playwright who got a bad review burst into the office and screamed, “Clay Felker! Your days are numbered,” prompting the entire staff to stand up and cheer) lost the place to Rupert Murdoch, the penultimate bigger fish who knew not to mess with a moneymaker no matter what anti-Republican swill it published. After that came Leonard Stern, the pet-food magnate, who paid an unthinkable $55 million in 1985. By 2000, Stern sold out to a consortium of faceless bankers and lawyers for $170 million. Now there was Lacey, almost certainly the only Voice owner to get his kicks from revving his mustard yellow Mustang Cobra past 100 while cruising the Navajo Reservation.

Actually, Lacey, who described himself as “this year’s Visigoth, the new asshole in charge,” his longtime partner, Jim Larkin, and their New Times Media corporation weren’t exactly taking over completely. They were merging with Village Voice Media, which includes the Voice and five other “alternative” newspapers, most notably the L.A. Weekly. New Times was getting 62 percent of what was being called the “business combination,” leaving VVM with the other 38 percent. Subject to Justice Department approval (more on this below), the merger will create a seventeen-entity mini-empire reputedly valued at $400 million. Together, the NT-VVM papers will reach as many as 4 million readers, dispensing “alt” staples like club listings, movie reviews, and reams of smudgy sex ads, along with local and a smattering of national reporting.

This was a long way away from 22 Greenwich Avenue and a dime at Union newsstand. Still, as Village Voice management changes go, Lacey’s visit to the paper’s offices at 36 Cooper Square was far from classic. Nothing iconic happened as with the 1974 Felker takeover, when star writer Ron Rosenbaum ripped up his (meager) paycheck in the New York editor’s face, saying there was “no amount of money” that could make him work for “the piece of shit” the Voice was certain to become. Rosenbaum then stormed out, a dramatic gesture, topped only by Felker’s puzzled reaction: “Who was that?”

Later, in the great rebellion of 1977–78 that greeted the Murdoch regime, the Voice staff commandeered the office in support of editor Marianne Partridge. Partridge had been hired only two years before by the previously despised Felker, but in Voice Land, dread of the future usurper always exceeds the virulent hatreds directed at the current one. Murdoch’s choice for editor, David Schneiderman, was barred from the newsroom, forced to cool his muted jets for six months in an office on Fifth Avenue.

The great takeover of 2005 inspired no rampart-mounting. No one at the Voice seemed to know much about the impending merger, and when the announcement did come, staffers had to read about it in the New York Times and the Washington Post, the Voice’s once lively “Press Clips” column apparently not deemed worthy of a scoop. Few were even aware Lacey was in the building.

This was too bad, since Michael Lacey, Jim Larkin, and their New Times papers offer much potential fodder for traditionalist Voice fear and loathing. First off, there was the old Clear Channel saw, how the New Times–VVM merger would further inhibit the already highly constrained alt-media world, all but stamping out the woolly idiosyncrasy prized by what back in the Stone Age used to be called “the underground press.” This owed to the troubling “cookie- cutter” nature of the New Times model, the fact that NT publications in such disparate locales as Broward County and Dallas tended to bear a strong resemblance to each other. Critics charge this is all part of NT’s lean, mean anti-local bias orchestrated in no small part by its national-advertising arm, the Ruxton Media Group. Politically, the NT approach also raised hackles. Lacey detractor Bruce Brugmann, editor of the independent San Francisco Bay Guardian, summed up NT’s stance to the current political landscape as “frat-boy libertarian, leering neoconism. They don’t endorse political candidates. To them it is one big, cynical joke.”

Beyond this, despite a consensus that New Times often published excellent local investigative stories, there was the sense that Lacey and Larkin’s papers were vicious corporate sharks. “These guys don’t want to compete, they want to annihilate you, put you out of business,” Brugmann said. This recklessness sometimes spilled over into the copy itself, such as in the recent Arthur Teele Jr. tragedy in Miami. The Miami New Times ran a story saying that Teele, a city commissioner indicted on corruption charges, had had numerous meetings with male prostitutes. The piece, called “Tales of Teele: Sleaze Stories,” was based primarily on specious, unproven police reports. Many considered the story unnecessarily scurrilous, especially after Teele committed suicide the day it appeared.

Lacey acknowledges the Teele story as a disaster. “You can’t publish unsubstantiated police reports. We were irresponsible.” A month later, the Miami New Times editor of eighteen years, Jim Mullin, resigned.

But you rarely find Mike Lacey on the defensive. Born in Binghamton, New York, son of a construction worker, attendee of Essex County Catholic schools in Newark, which makes him by far the bluest-collared owner in Voice history, Lacey likes to mix it up. Verbally, physically, emotionally, it is all good to him. In response to Bruce Brugmann’s attacks, Lacey published a many-thousand-word rejoinder in his Oakland-based East Bay Express titled “Brugmann’s Brain Vomit.” Warming up by comparing Brugmann to “a needy ferret blogging,” Lacey called his fellow editor “a bull-goose loony” and wondered why he was even wasting his precious time “engaging a homeless paranoid in conversation about the contents of his shopping cart.” For good measure, Lacey fingered one of Brugmann’s backers as the late Donald Werby, who in 1989 was “indicted on 22 counts of having sex with underage prostitutes and paying for it with cocaine,” the same Donald Werby who was “a friend and patron of Anton LaVey,” who “underwrote LaVey’s efforts in the Church of Satan (no, really).”

It was this spirit of healthy confrontation that left Lacey frustrated at not being able to set the record straight with the legendarily chippy Voice staff. As it was, all Lacey got to do was ride up in the elevator, discuss a few generalities with some Voice higher-ups behind closed doors in the office of current editor Don Forst, and “check out the urinals.” Later on, Forst, the grizzled former daily-paper guy who resides incongruously atop the Voice masthead, took Lacey on a small tour. They walked past Cooper Square to the true key juncture of the neighborhood, the Starbucks on Astor Place. “Forst said this was where it was at,” Lacey related, “because that’s where NYU kids go, our supposed target audience.”

It was all pretty tame, Lacey said in his gravel-pit baritone. “I didn’t get anything stuck between my shoulder blades. Someone could have at least told me to fuck off. What a disappointment.” But there was nothing to be done about it. “John Ashcroft said no,” Lacey said—i.e., the terms of a media merger of this size forbid a new owner from “engaging in major business practices,” which includes addressing the staff or even touring the building until after a 60-to-90-day review period.

This didn’t stop Lacey from explicating what he would have told the Voice staff should they have brought up any number of topics, like, say, that New Times papers are conservative. “Look,” Lacey said, “just because I don’t have eight reporters kneecapping George Bush doesn’t make me conservative. One is enough; the other seven can be looking for dirt on local politicians. The idea is not to let politicians get away with shit. Our papers have butt-violated every goddamn politician who ever came down the pike! The ones who deserved it. As a journalist, if you don’t get up in the morning and say ‘fuck you’ to someone, why even do it?

“Look, a lot of people think I’m a prick. But at least I’m a prick you can understand. I don’t sneak up on you. You can see me coming from a long way away. Like the Russian winter.”

It was quite a performance, aided by the fact we had just downed three bottles of Italian wine, at $120 per. But what about the Village Voice? Not to denigrate the fine towns where New Times operates its freebie papers, but this was New York City and we were talking about the Village Voice. The Village Fucking Voice—not just one more property for Mike Lacey and Jim Larkin to insert into their strip-mall portfolio like a Kansas City Pitch, or a St. Louis Riverfront Times, or a Denver Westword.

“I’m sick of that crap,” Lacey said with a snarl. “Like we’re from Phoenix or some Wild West dung heap and we’re hayseeds. Like we don’t know what’s up … of course I know we’re talking about the Village Fucking Voice!

“Listen,” Lacey said, narrowing his eyes, “we started the Phoenix New Times back in 1970 at Arizona State University because the campus police said we couldn’t lower the flag to half-mast after Kent State. We didn’t want to burn down the ROTC building, we just wanted to lower the flag because it was the right thing to do. Somehow, we thought we needed to start a newspaper to get the nuances of that point across. And to have a little fun. Throw a little spirit of Mad Magazine into the debate.

“It wasn’t easy. I was ready to sell blood to keep the thing going. We’re successful because we’re smart, we outwork everyone. Our papers have broken stories. We had the thing about sexual abuse of female cadets at the Air Force Academy. We had the story about mishandling nuclear waste in San Francisco. Not the San Francisco Chronicle, not the Los Angeles Times. Us. We’ve won more than 700 awards. But I never stopped thinking about the Village Voice. I know what it was. I know what it is now.

“I’ve got my own focus group in this town: 20-year-olds, 30-year-olds. They say, the Village Voice, no one reads that. I can’t walk around town hearing nobody reads my paper. It wrecks my day. That’s got to change. We’re here to play, and anyone who likes to play like we play can play along.”

Thanks for the phrase go to Cynthia Cotts, who used to write the Voice “Press Clips” column (she reported on New Times’ failed 2000 attempt to buy the Voice, calling it a “hostile takeover”). “The Village Voice,” she said. “It is the wound that never heals.”

This I take to mean that once you are a Voice Person—no matter how many years go by or the number of jobs you do—you will always be a Voice Person. Even those without holes in their jeans, like Ken Auletta, who once wrote the Voice’s city-politics column, “Running Scared,” back in the early seventies, agree.

“Yeah,” Ken said. “It’s like the blood on Lady Macbeth’s hands.”

It repeats. Like: A couple of years ago I was feeling extra crazy, so a friend gave me a shrink’s name. I called, and this deep Donald Sutherland voice came on the line. Yes, he said, he had time, I should come by his office on Tuesday afternoon. “Eighty University Place,” he said, sonorously. Sensing hesitation on my part, the shrink asked, “Do you have a problem with that?” No, I said. It was fine. The mere fact that I’d spent four years in the building working for the Village Voice wouldn’t interfere with my therapy, would it? Yet when I arrived for the session to find the shrink’s office on the fifth floor in the back, I had to demur. “Don’t think this is going to work for me,” I told the puzzled analyst.

“Fifth floor in the back, it was just too dense,” I told David Schneiderman when I went to see him a couple of weeks ago. Schneiderman laughed. After all, Schneiderman, whose brother Stuart is a leading American authority on the French psychiatrist Jacques Lacan, was well familiar with the fifth-floor rear of 80 University Place, circa 1979. That was where the editor-in-chief’s office was, the same glassed-in sector where I was hired by Marianne Partridge and, some years later, fired by David Schneiderman. (That should take care of any disclosure issues.)

Not that either of us was holding a grudge. The firing was passed over as a regretful misunderstanding, a product of youth. Schneiderman was a good sport about the whole thing. He could afford to be, since he’d gone from staff-mandated exile, to editor, to publisher (under Stern), to CEO, and now stood to make a rumored half a million dollars for brokering the merger with New Times. He didn’t even flinch when I told him I knew from the moment he walked in the door he was bad news, because if there was anything a 1978 Voice Person understood, it was, don’t hire anyone from the New York Times. Certainly not some deputy from the the op-ed page—and never, ever, make him the editor-in-chief.

That’s because back then a Voice Person didn’t dream of working up to some swell job on the “Metro” section. The New York Times was the enemy. You knew it could send out its mirthless Maginot Line of Princetonians and it wouldn’t matter. If you traveled light and right, you could still beat them to the spot. They could be had. Putting a Timesman, from Johns Hopkins, in charge of the Voice struck me as a sick Murdochian joke, a total capitulation.

Does the Voice’s new owner understand what he’s just bought? “I’m sick of that crap,” he says. “Like we’re from Phoenix or some Wild West dung heap and we’re hayseeds.”

But what did it matter now? Twenty-seven years later, Schneiderman was still there, still the boss. All those wild people, all those famous bylines, and he’d outlived almost every one of them. He was the dominant personality in the entire history of the institution.

He didn’t look all that different, apart from the gray hair. He was still that same lantern-jawed, hingey-looking neo-Dickens–Sephardim in a Brooks Brothers shirt. His status had changed, though. At 36 Cooper Square, he rode upstairs in what most people at the place referred to as “David’s private elevator.” Now the CEO of Village Voice Media, he’d become something of a ghost around the office. Longtime Voice people, including those he used to edit, said they saw him maybe once or twice a year.

“I don’t even know why you came over here,” Schneiderman said, smiling. “Because you’re going to write the same story everyone does, how the Village Voice isn’t what it used to be anymore. But those people say they don’t read the paper, so how would they know?”He could keep using that line to his uptown friends, but it wasn’t going to work with me. Because I read the Voice—every week, if only because there was stuff in there worth reading: my homey Hoberman’s movie reviews, the great Ridgeway, Wayne Barrett, and Tom Robbins, still kicking municipal butt. Still, it was so, the paper wasn’t what it used to be. But why was that?

We kicked around the usual rationales: the end of the left (Schneiderman said it was “a dead movement”), the demise of bohemia, changes in the youth culture, and the decision, in 1996, to go free, that is, give the paper away, as all “alt” papers are. Told that many writers felt that the impact of their work had been diminished when the paper went free, Schneiderman scoffed, adding that there was no choice. “We were below 130,000 circulation, down from a top of 160,000. Now the circulation is 250,000 … wouldn’t you rather be read by twice as many people?” Well, yeah, but I wondered where Schneiderman got this quarter-of-a-million number from.

“Returns,” he said. “We’ve got only 1 percent returns. That’s where the number comes from.”

“You must be kidding. Are you counting those hundreds of papers that are thrown away because some dog pissed on them?” How could he claim 250,000 individual readers when most picked up the paper to see what time a movie began, threw it away, and got another one for the next movie?

“No one does that.”

“I do.”

“You’re not typical.”

No, Schneiderman said, it wasn’t going free that hurt the paper. It saved the paper. Kept it going, making money. The true challenge was, as everyone knew, the Web. “Craigslist is the biggest single crisis the Village Voice has faced in its whole 50 years,” he said with out-of-character vehemence. Schneiderman really had it in for “Craig,” whom he said had cost the Voice more than a few million dollars in real-estate classifieds alone.

“That guy,” Schneiderman said, “he puts himself on a pedestal, says what he’s doing is for the people, but that’s a lie. He’s only in it for himself, like everyone else.”

It was right then, looking around Schneiderman’s office, with its displays of the Village Voice Media holdings—covers of the Minneapolis-St. Paul City Pages, the L.A. Weekly, Orange County’s O.C. Weekly, the Seattle Weekly, and the Nashville Scene—that it occurred to me how far we really were from the glassed-in office on 80 University Place. I was speaking to a fundamentally different person than the one who fired me 25 years before. Our particular visions of the Village Voice could no longer be the same. My paper was a chimera of longing and never-quite-requited obsession, an object to be held in the hand, sweaty ink on fingertips. Meanwhile, Schneiderman’s view, although indescribably deeper owing to his nigh three decades inside the beast through who-knew-how-much thick and thin, had a more abstract air. He was talking of the paper as a piece, albeit a big one, on an infinitely larger playing field.

Schneiderman grinned at this notion and said, even if he “woke up every morning thinking about how to protect the Village Voice,” quite frankly, exactly what went into the paper had ceased to be his major concern long ago.

He said, “If Leonard Stern hadn’t come here and made me a publisher, I think I would have been gone after five years. That’s pretty much the burnout period for an editor at a place like this. Leonard helped make me into a numbers guy. Of course I’m still a word guy, but there’s a longer shelf life to a numbers guy. That’s been the real fun for me, flying around, looking after our papers, handling the business side.”

Schneiderman didn’t worry about the Voice edit because, he said, he had trust in his editor, Don Forst. Indeed, the bantam, septuagenarian former head of New York Newsday has been Voice editor for nearly a decade, longer than anyone has ever held the job. Asked why he got the position, Forst, nothing if not blunt, said, “I’m a very good manager. I can handle a tough room. But really, I don’t know. I needed a job.”

It was clear from the start that Don Forst’s paper was to be a wholly different animal. One of the first acts in the Forst era was the firing of Jules Feiffer, universally regarded as the paper’s most visible and beloved symbol. “It wasn’t just that they canned Jules,” says one Voicer who, like almost everyone else, preferred to remain nameless. “It was well known that they thought he was making too much money, if you can call $75,000 too much for Jules Feiffer. They’d been after Karen Durbin, the last editor, to get rid of him. But what really blew people’s minds was when Forst said there wasn’t going to be any shit about it, none of that letters-from-the-outraged-staff stuff that has always gone on at the Voice. The staff tried to buy an ad to complain, but the ad department said they wouldn’t run it. That’s when we knew we’d entered a period of malign neglect at the Village Voice.”

Once, for better or worse, the Voice was a “writer’s paper,” but the I word was soon banished from most Voice copy. “I am simply not interested in people’s individual psychodramas,” Don Forst said. Story length was restricted, with few features running longer than 2,500 words. “Our younger demographic doesn’t like to read long stories,” said the 73-year-old Forst. One day, Forst dropped a copy of The Old Man and the Sea on the desk of the late Julie Lobbia. “Your sentences are too long,” he said. Most destructive, according to most, has been the redesign of the arts pages, allegedly at the behest of the ad department. In the old days, a lead Voice critic could address the week’s fare in a free-ranging essay of about 1,400 words. Now it was decreed that they produce three separate “elements” on the page, each dealing with a separate film, play, or piece of music. The “big” piece runs 800 words.

“It is depressing,” says one critic. “I thought if I stayed serious, I’d create a body of work that might win me a Pulitzer. At least I had the hope. Now what can I show, these little postage stamps?”

Meanwhile, management, always legendarily cheap (Schneiderman once declared that no Voice reporter was allowed to use 411; the policy was dropped after people started calling 1-718-555-1212, which was more expensive), kept downsizing. Gary Giddins, only the best jazz critic in the country, was pushed out after three decades. Sylvia Plachy, who along with James Hamilton had given the Voice a very distinctive photographic look, was laid off, apparently to save her $20,000 stipend. Her son, the actor Adrien Brody, an office regular back in his toddling days, often making copies of his face by pressing his nose to the glass of the Xerox machine, came to help her move.

“He had this baseball hat jammed down over his head, demanding to know who fired his mother,” one observer recounts.

Hearing some of this, Michael Lacey frowns. He’d been ranting about how even though he’d come from a union household, and his brother, who helped build the World Trade Center, was the president of a midwestern boilermakers local, which was no “pussy union,” he had no use for organized labor. This didn’t mean he expected any trouble from the Voice union. What he hoped would happen, Lacey said with confounding plutocrat noblesse oblige, was that the Voice employees would realize a union wasn’t necessary, “because we take good care of our people.”

Word of bad morale at the Voice, however, brought Lacey up short. Although no slouch with the downsize scythe himself (mass-firing tales are legend in the New Times canon), Lacey shook his head at stories of layoffs. “You don’t get rid of good people just to save money. They’re too hard to find. You don’t discourage them. You want a lively newsroom, some action. Sturm. Drang. That place seemed dead.”

He couldn’t seem to get over David Schneiderman, his new partner, referring to himself as “a numbers guy.” He liked Schneiderman and had learned not to underestimate him. But “a numbers guy? … Sounds like death. I can’t even balance my checkbook.“It’s so sick the way most of the business runs. The top editors don’t edit. Never touch a piece of copy. What do they do all day, think beautiful thoughts? The way we do it, the editors have to write too. They should never forget how hard it is, the fucking agony of it. I make myself write and report. It kills me, but I do it.”

Then, loud enough for the other diners to turn around, Lacey declared, “God help me, I’m in a business of weenies!”

The next day, I was talking on the phone to Robert Christgau, the Voice’s archetypically thorny “Dean of Rock Critics.” He asked me what I thought of Michael Lacey. I said he’d probably turn out to be a nightmare, but so far I kind of liked him.

“What do you like about him?” Bob demanded.

“I don’t know … he’s got this bonkers sincerity about him. Who knows what he’ll do, but I got the feeling he genuinely wants to make the paper better.”

Christgau snorted. “I doubt if his conception of how to make the paper better conforms to mine.”

Then he hung up. Conversations with Bob Christgau have a habit of being truncated without warning. Often voluminous on the page, verbally he retains a compelling gift of concision. After Nelson Rockefeller reputedly died after sex with the young Megan Marshack, Bob said, “If I knew it would kill him, I would have blown him myself.” When John Lennon was shot, he bemoaned, “Why is it always Robert Kennedy and John Lennon, not Richard Nixon and Paul McCartney?” Personally, I’ve always treasured Christgau’s assessment of my work. During the era of the Reggie Jackson Yankees, I wrote a not particularly friendly piece about the team. Christgau, a Yanks fan, came over to my desk.

“Read your piece,” he said. “Really sucked.” Then he stomped away. I never even got a chance to thank him for his input.

Christgau’s comment about Mike Lacey seemed likewise to the point, a perfect Voice Person reply. To wit: Sure, Lacey and his crew could take over, as Leonard Stern, Clay Felker, and Murdoch had done before. They could fire everyone, turn the paper into a desert flatter than Camelback Road. They might temporarily own the paper’s little red boxes, its famous name. But they would never control its soul, never truly silence the legitimate keepers of the VV logos.

Coming from Christgau, now 63, more than half his life spent at the paper, it was a defiance you had to respect. This was especially so, since of all the supposed Village Voice “dinosaurs,” those masthead survivors who never seem to go away, nobody comes in for as much sniping as Bob. Typical is the commentary of Russ Smith, the snarkish “Mugger” of the New York Press, the most recent bottom-feeder paper whose entire existence is bound up in the fact that it is not the Voice. Smith said the merger would certainly mean “sayonara to Robert Christgau, who could then be reached at either an upstate retirement community or the publicity department of a record company.”

No doubt much of the ire directed at Christgau stems from his long-running “Consumer Guide” feature, in which he hands out letter grades to discs each month, a practice that caused Lou Reed to once refer to Xgau as “an asshole” on a live record. The subtext: School of Rock might have been a hit, but “rock as school” will never be, and what’s a 63-year-old guy who has never burned a CD got to say about pop music in this day and age anyway?

The answer is quite a lot, if you care to listen. Present from the moment rock became “serious,” Christgau, like other all-inclusive Voice critics J. Hoberman and Michael Feingold, knows everything from the beginning to now and continues to put it to the page, albeit a tad densely. Indeed, writers like Christgau—and this probably goes for Nat Hentoff, too, still batting away on his Selectric 3 and too busy to have me come by because “with the Constitution so endangered, it needs my total attention all the time”—could have existed only at the Village Voice. This was the realm of the non-J-school, self-invented, pop-cultural autodidact, a place where the high tone met the vulgar and an Everyman could hawk his expertise. It is no coincidence that many of the older Voice writers come from working-class, outer-borough backgrounds (Christgau’s father was a fireman, Richard Goldstein’s worked at the post office), people who threw in their lot with the egalitarian vision of the paper where they could write what they wanted. What’s the term limit on that, even in a journo-world desperate to “get younger”? No doubt Christgau will go to his grave positive that the Voice, the true Voice, exists only as “a left-wing, intellectual, writer’s paper,” and believe me, he is not likely to go quietly.

“It might sound strange, but people my age are much more suited to working at the Voice the way the paper is these days,” says Jarrett Murphy, a 29-year-old front-of-the- book reporter. “We came into this business knowing it was a potentially dying industry. I would have loved to have worked at the Voice when it was great. You just have to look at the 50th, see all those covers, and it gives you a chill. But you have to be realistic, deal with what is.”

It made you wonder if it might have been better to have taken the paper out and shot it, like a used-up racehorse, before, say, the humiliation of going free.

“Don’t think I would have liked that,” said Richard Goldstein, who worked at the paper for 38 years in an unparalleled career that comprised more or less inventing rock-and-roll criticism and establishing an aboveground media outlet for the gay community. This is not to mention uncounted hours of engaging in all intra-paper turf squabbles (the front-of-the-book “white boy” news writers have always battled the art-culture people in the back). Now 61, Goldstein, raised in a Bronx housing project, is one more perfect Voice Person who started reading the paper early, sussing out that a trip on the Woodlawn-Jerome line to MacDougal Street could make even him a bissel cool. Present for every regime change in the history of the paper, Goldstein will not be around for the New Times era. He was fired in the summer of 2004, after an increasingly fractious relationship with Forst.

Goldstein contends that Forst has waged a long-running gay-baiting campaign against him. “He said things to me I hadn’t heard since the playground in the Bronx. He just kept doing it. It was sick.” In 1999, in accordance with Voice policy on verbal abuse, Goldstein wrote a letter of complaint. It was after that, he says, that Forst retaliated by “taking away my job.” Goldstein was cut out of meaningful decisions at the paper. “I hired and edited Mark Schoofs, who won a Pulitzer Prize; I wrote ‘Press Clips’ when they needed someone. It wasn’t like I was slipping. Then one day Forst comes in and tells me I won’t be writing for the paper and I should just think of myself as a ‘cobbler.’ I don’t want to be maudlin, but the Voice was such a big part of my life for so long, to have it disappear was incredible.” Eventually, Goldstein wrote a letter to David Schneiderman, telling his side of the story.

“I trusted him. In my mind he still represented the Voice I knew. Then I got a call from the publisher, Judy Miszner, and she’s telling me, ‘So you’ve decided to resign.’ I said, ‘What?’ Their attitude was, if I couldn’t get along with Forst, I had to go. I couldn’t believe it. This, at the Village Voice! Then they started giving me a hard time about my severance. I’m there 38 years, and they’re trying to stiff me.”

“Richard broke the chain of command,” says one Voice writer. “That was the unforgivable thing.”

Finally, Goldstein filed a federal suit charging the Voice with, among other things, sexual harassment and age discrimination. “Even after all that, I didn’t want to hurt the paper,” he says.

Should you care to, you can go to TheSmokingGun.com, the Website started by Bill Bastone, former Voice writer, to read the court documents in the case of Richard Goldstein, plaintiff, v. Village Voice Media, defendant. In it, Goldstein accuses Forst of calling him “an ass-licker,” “a slut boy,” “a pussy boy,” and saying he walked “like a ballerina.” After years of hearing about dreary Voice p.c., the case makes surreal but grim reading.

Asked if the Village Voice was “the biggest basket case” of his acquisitions, Mike Lacey bugged his eyes like, “Duh,” and said, “Without a doubt.” But this only raised the stakes, Lacey said, because the Voice, and New York, was “such a big deal.”

“This is it: unique, special, fucking exciting,” Lacey said, walking through a driving rain on Ninth Avenue in the Thirties. He was spritzing, free-associating about what he might do with the Village Voice.

“I like the arts coverage. But we’ve got to work on the front of the book. We can’t have stories cribbed from the Net. We have to get out of the office. Robbins seems good. He’s a reporter. But I can’t believe they don’t have a front-of-the-book columnist, someone to give a sense of the fabric of what the streets are like. Come back, Jimmy Breslin!”

He was steaming now, talking louder, stomping across the avenue toward Manganaro’s Hero Boy. “We could cover the courts. Have a reporter down there. We don’t have to be Time Out.”Did he feel he had a particular responsibility to the Voice staff, especially those writers long identified with the paper? “Of course, you want people who love the place, but this is a business that is based on performance. It isn’t a legacy.”

No doubt this was going to be hard, Lacey said. He too was having some difficulty buying into David Schneiderman’s circulation numbers. “Have to see about that,” Lacey said, regretting that he wouldn’t be able to move to New York to keep an eye on things. “No, I got this 16-year-old. He drove the car through the garage wall back in Phoenix. He requires surveillance.”

Then Lacey said he had to rush. He was flying out in the morning to L.A., where he’d scheduled a meeting at the L.A. Weekly. It promised to be tense, especially after New Times’ sometimes vicious, ultimately losing competition with the Voice-owned Weekly. There’d be hard feelings, fences to mend, necks to snap back into joint. It was all a giant juggling act, Lacey said. With seventeen papers, you couldn’t play favorites.

Meanwhile, the Voice threw a little party at Bowery Bar to celebrate the 50th-anniversary issue. The turnout was good, especially considering the announcement of the merger and how few whose work had been chronicled in the issue were invited or able to show up. (Newfield, Joel Oppenheimer, Joe Flaherty, Mary Nichols, Geoff Stokes, and Paul Cowan, among others, had a good excuse: They were dead. Many others just hated the paper.) A cake decorated with the famous Voice logo was served, and David Schneiderman, after laughingly introducing himself as “that mystery man,” made a speech. Someone quoted Alexander Cockburn’s famous line from a previous Voice takeover, how the change made him “dizzy with the prospect of a whole galaxy of new asses to kiss.” Then, with the dinner crowd arriving, the party was over. The Voice people walked out onto the Bowery. If you looked to the right you could see CBGB, where the drag queen Jayne County once knocked cold Handsome Dick Manitoba of the Dictators with a mike stand. James Wolcott wrote a really cool story about it for the Voice. Soon, they might close CBGB because Hilly Kristal won’t pay higher rent. But that was the way it went. It was a new world out there, with new times to go with it.