With Amy Larocca

Bonnie Fuller knows how to make an exit. She’s made six of them in her twenty-year career as an editor-in-chief, and not all of them have worked out so well, but this one went off with the diversionary panache of the casino heist in Ocean’s Eleven.

Things were going brilliantly at Us Weekly: Newsstand sales were defying gravity. Her boss, Wenner Media general manager Kent Brownridge, told the Post on May 30, “It means Bonnie is a very rich girl,” since “the $1 million contract” the paper noted she signed earlier this year had a big circulation bonus clause. On June 17, Fuller congratulated the staff on their success with a champagne toast.

“She plotted it out so beautifully,” marvels Us senior editor Catherine Hong, who had just had a frosty meeting with Fuller after giving her notice. “She made it sound like it was going to inconvenience her,” she says. “And she was leaving the next day. Nobody knew. It was very convincing.” To everyone: Her staff thought she had a signed contract just as much as Brownridge and Jann Wenner thought they’d made a deal to keep her there. Nobody knew that she’d spent “twelve to fifteen hours” in clandestine meetings with tabloid king David Pecker (“I could say it was someplace where nobody would recognize us,” he says) over the previous couple of weeks, working out the terms of her defection to American Media.

On Thursday, June 26, much of the staff of Us Weekly wasn’t even in the office, since they’d closed a double issue the previous Monday—a Fuller classic, fuchsia, purple, and yellow girlie newsstand-candy featuring three exclamation points and a digitally conjoined photo of Reese Witherspoon and Kate Hudson glowing pink over the headline HOT MAMAS! WHY HOLLYWOOD’S SEXY YOUNG SCREEN QUEENS WANT BABIES NOW. Her executive editor, Janice Min, was away in Tuscany, and—as Cindy Adams had dutifully noted in her column earlier in the week—Fuller would be off to Hawaii Friday morning with her family to celebrate her twentieth wedding anniversary. Even the Us publicist, whom she’d pestered to keep her in the press, was on vacation.

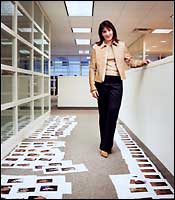

Not a caption got printed in Us Weekly without passing through Fuller’s uncompromising filter, which meant that staff people were waiting with 30 pages of proofs for her to go over before her vacation while their boss went off to meet with Wenner in his corner office. She never returned. The staff waited. At around four o’clock, the phones lit up—friends asking, “Is Bonnie really going to The Star?”—and tech support came and carted away Fuller’s assistant’s computer, since she didn’t use her own. A bit after five, jacketless and smiling, Wenner gathered the staff in the glass conference room and announced she’d left, wishing her “godspeed.” He didn’t know what had hit him.

The staff retired to the gloomy bar at the Warwick Hotel to wonder what was going to happen next. “When Jann came and talked to us and said, ‘Bonnie’s about to get on a plane to Hawaii,’ it was like the last scene in a movie,” Hong says admiringly. “You could just picture her sitting in first class, sipping a cocktail.”

People have been wondering what movie Bonnie Fuller sees herself starring in ever since she was imported from Canada to be editor of the teen magazine YM in 1989. In some ways, she’s the Joel Schumacher of editing: a single-minded producer of superefficient blockbusters, instinctively mass-market. She’s dumbed down every magazine she’s ever worked for—Us to the point of its being little more than a slickly packaged, guilty-pleasure-inducing collection of paparazzi photos—by stripping away anything that the reader wasn’t going to be instantly interested in.

“She’s not editing for anyone else in New York, she’s not editing so other editors can cluck over her artistry,” says Mark Golin, creative director of Time Inc. Interactive, who worked for her at Cosmopolitan.

But Fuller’s serial successes have changed editors’ worlds nonetheless, putting pressure on them to think about what the reader wants to know more than what they might want the reader to know. “Bonnie is like no-fat editing,” says Golin. “Not low-fat, not 15 percent, but no-fat. She doesn’t put a thing in the magazine that she doesn’t think will work … She tortures every caption.”

And every caption writer. Fuller is legendarily difficult to please, and so obsessed with the product that she churns through staff, regularly burning out editors with dismissive treatment and punishing late nights. But she gets bang for her buck: She’s posted hefty circulation gains at every magazine she’s touched, including Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, and Glamour, minting money in turn for Gruner + Jahr, Hearst, and Condé Nast. Until last week, the only surprise turn in her juggernaut of a career was the falling-out with Si Newhouse that led to her ouster from Glamour. Rumors were flying that she’d been jockeying for the editor-in-chief’s job at Harper’s Bazaar; staffers reported seeing her working on a mockup of the fashion book around the Glamour office—a charge she has dismissed as “urban myth”—and she had withheld signing a new contract that had been on her desk for months. But she didn’t get that job—it went to Glenda Bailey—and she was quickly pushed out of the one she had, the contract taken off the table by a miffed Newhouse.

When she was hired for the Us job, it was not only a save for Wenner, who had lost Terry McDonnell to Sports Illustrated after several months of struggling to establish a niche for the newly launched weekly, but a comeback for Fuller. In the eight months without her name on a masthead, she had been cooking up a shelter magazine start-up for Meredith Corporation and writing a personal how-to book called From Geek to Oh My Goddess: How to Get the Big Career and the Big Love Life and the Big Family—Even If You Have a Big Loser Complex Inside.

Indeed, even after all of her success—starting with the editorship of Flare, a Canadian fashion magazine, at 26—people she’s worked with can’t resist observing that she’s never lost her loser complex inside. She’s probably referred to as the “geeky girl from high school” more than any other woman in publishing.

Maybe that’s the “Rosebud” explaining her enormous drive. There’s a crude, force-of-nature quality to Fuller’s personal style that leads everyone who works for her to try to figure out what causes it, if only to determine how best to stay out of her path. “We’d do amateur psychologizing about her,” says a former staffer. “I think she’s absolutely clueless about how she affects people.”

Or, scarier, maybe she’s not clueless. “She would fuck with you,” says an editor. “She would fuck with people if they gave off fear. She respected people who were brave and seemed resilient.”

“If you’re a perfectionist, you’ll love working with her,” says Jane Hess, one of Fuller’s oldest friends from Toronto. “But if you want to do the basic job and go home at five-thirty, you won’t. She likes people like herself. She’s not interested in people without ambition.”

Punishing hours were routine at all the books that have had Fuller at the top of the masthead, but her tenure at Us will long be remembered as an editorial forced march of unprecedented pain, with regular all-nighters the first six months, and even after that, work till 3 a.m. several days a week. There were no windows in the newsroom; editors would sometimes stumble out to discover it was dawn. “She was there to do a job,” says a sympathetic staffer, “and everybody else needed to be on the same page: Get onboard or get out. There were always people crying and losing it in the bathroom.” A former Us editor says bitterly, “She just upturns every life in her way in pursuit of her goal.”

But even employees who bailed out express awe at her ability to execute her vision and produce consistent commercial successes. “Her memory is just on point,” says one. “She doesn’t miss a thing.” Says an employee who didn’t leave: “She’s one of the smartest, hardest-working people I’ve ever met. She knows what she wants. It’s hard to keep up with her.” And for the young, largely inexperienced staff, there was an esprit in going up against People, in doing something new, in changing the industry.

Part of the brief against Fuller is her cavalier treatment of the people who work for her. One editor told of the time—it was July 3 last year—when everyone was trying to get away for the holiday and Fuller went out for a pedicure, leaving instructions that no one could leave till she returned—which she finally did two hours later. And the office was structured around her idiosyncrasies. “Bonnie doesn’t use the computer,” says a woman who worked with her. “She looks only at hard copy. And you couldn’t send her e-mails directly.”

To her employees, Fuller could be shockingly, woundingly blunt. “She just can’t help herself sometimes,” says one who was on the wrong side of a Fuller tirade. “She doesn’t have that mental check. She just says whatever she thinks when she thinks it.”

But much of the problem had to do with unbridled perfectionism. She’d tear up things that had been approved and have editors work on different stories for the same slot because she hadn’t made up her mind. None of these are federal crimes—remember Tina at The New Yorker?—but they were demoralizing.

At one point, an efficiency expert was brought in to attempt to diagnose the difficulties. Little came of it, however. “Bonnie couldn’t believe that it was her fault,” says an employee.

Fuller’s trust in her own judgment is absolute. “Bonnie’s not into brainstorming,” says an editor. “Her method is to take the first idea that comes into her head and run with it.”

But many of the ideas that come into her head are uncannily in sync with a broad base of women’s-magazine readers—especially those who buy at supermarkets. “Bonnie is a fan,” says another editor. “She is her reader—that’s why she understands her reader. These are questions that she genuinely has.” When focus-grouping potential covers with a gaggle of staff—mostly women in the Us demographic, 25 to 39—she would repeatedly bark: “No thinking! No thinking! It’s got to be visceral! Visceral!”

For much of her tenure at Us, Fuller’s climbing numbers kept Wenner at arm’s length. But as the months wore on and their steady rise hit some turbulence, Wenner, a legendary micromanager in his own right, stepped in, even getting involved in story selection—the tyrant became the tyrannized. “I’ve been in her office when he called her,” says an ex-staffer. “She goes from talking to me to acting like me being talked to by her.”

She liked to complain about her own bosses to her staff. “She would often say, ‘Why are they doing this to me?’ ” after the money people complained about the vast costs associated with missing production deadlines, says an ex-staffer. Many speculate that Wenner’s growing interference played a large role in Fuller’s impulse to look for a way out. Others who’ve worked with Wenner say Wenner’s hard-line contract tactics are so disagreeable as to push just about anyone to consider her options. “We don’t want her to work here if she doesn’t want to work here,” says Wenner Media’s Brownridge, who adds that a lawsuit over her contract is unlikely.

“I think Bonnie is a real piece of work,” he continues. “It was fun to work with her. She’s very competitive and likes to win, which makes her good at newsstand. Some editors don’t want to know those numbers. They moan and act like that’s too philistine for them. She’s the first to call to ask what the numbers are. And the other thing that makes her tick is money. Bonnie is about money.”

Whatever makes her tick, it’s clear Wenner and Fuller understand each other. “She is cut from the same cloth as Jann,” says a former staffer. “He didn’t care if she was costing tens of thousands of dollars in late fees, as long as newsstand was up.” And among many who’ve worked for Wenner, there was glee that, with Fuller’s departure, he’d gotten a taste of his own medicine.

Fuller’s edges soften significantly when she’s not at work—or when one of her four children is around the office. “I’ve seen her with her husband and her kids, and she’s totally different,” says an almost envious staffer. “I’ve seen her daughter come into the office, and she dotes on her. I saw her give her husband a smile once that was so warm. These glimpses of a human being peek through, but they’re really, really rare.”

Home is a big, comfortably appointed stucco house in Hastings-on-Hudson. But family life hasn’t all been idyllic. Ten years ago, when Fuller’s older daughter was 2, the toddler underwent surgery for a benign brain tumor. Then, three weeks after Fuller started work at Us, her 5-year-old daughter was diagnosed with leukemia and began chemotherapy. Her mother fell seriously ill and began treatment as well. But the medical traumas didn’t put a dent in Fuller’s killer work schedule. She had no choice, she explained last fall. “I’m the breadwinner. I’ve got to support the family. I had not been working full-time for eight months before I came here, and it was important for me to have insurance.”

Michael Fuller is an affable, good-looking stay-at-home dad, as well-versed in the social intricacies of the Hastings seventh grade as his wife is in the marriage plans of Jennifer Lopez. He’s there in the morning to take the kids to school and his wife to the train, backing the car as close to the door as possible so his wife won’t get her camel-colored Manolos spotted by the rain. He’s been known to appear on closing night with dinner for his wife, and for Valentine’s Day last year, he quizzed the beauty department about her favorite products and delivered a basket of them, since she was working late.

In her Us office was a framed construction-paper heart that says HAPPY VALENTINE’S DAY. I LOVE YOU EVEN THOUGH I MITE NOT SEE YOU.

“She is much more like a man,” says Jane Hess. “You know how men can compartmentalize? She does that. The children’s sickness is a compartment for her, and she doesn’t open it at work.”

When she gave birth to her first child, she timed her contractions during a meeting at Flare, gave birth that night, and was calling the office at the start of the next business day. There were page proofs in the hospital bed after each of her children was born. And as for maternity leave, she packed up the baby and the nanny every morning and installed them in her office so she could breastfeed at work. When she takes a ski trip, she calls in from the slopes. At Glamour, she had pages FedEx’d to each stop of the Italian bicycle tour she took one summer.

In David Pecker, Fuller might have met her match. Pecker, too, has a reputation—he’s cultivated one, in fact—for not caring how he affects people. A blustery man with a bushy mustache and an outer-borough accent, he’s always been a bull in the Manhattan media’s china shop.

The union with Fuller almost didn’t happen. “I was having lunch with a very senior exec in the media business. I was saying, ‘I’m here in New York, moving Star back to the city,’ ” says Pecker, the former head of Hachette Filipacchi. “And I need to hire 30 people. I need somebody with the success of Bonnie at Us Weekly because everybody’s taking my readers. He said, ‘Why not talk to Bonnie Fuller?’ I said, ‘I read in Keith Kelly she had a contract.’ He said, ‘Do you believe everything you read? I could be wrong, but I don’t think the contract has been finalized. You should contact her directly.’”

So he did. Pecker had known Fuller from when he’d approached her, post-Glamour, to work on the test issue of Style 24/7, his planned fashion magazine. She turned him down, saying she wanted a permanent gig. (Style 24/7 hit the stands shortly after 9/11 and soon failed.) This time, “everything happened very, very quickly,” he says.

He was already looking for an editor for The Star—there were plans to move the offices up from Boca Raton to 1 Park Avenue. Steve Coz, the editorial director of the tabloids, had been very publicly interviewing people for that job, though he’d also been dismissing the idea that, despite efforts to compete with Us and InTouch, The Star would go glossy. “Everybody talked about a glossy magazine, but I really didn’t intend to do it,” says Pecker. “Any changes you make with a magazine with 1.1 million newsstand, it’s like turning around the Intrepid in the Hudson.”

But with a copy of Us, Fuller changed his mind: “She explained the new departments, the Fashion Police, the colors. It’s a quick read; you don’t have the 1,000-word stories. We talked about the changes since 9/11, the changes in meanness.”

Fuller made her name—and moved the newsstand needle—by pushing magazines down in the direction of tabloids. Now that she’s crossed the divide, she’s already pushing in the other direction, up toward legitimate journalism. “One of the issues that she did mention was paying for sources,” says Pecker. “She asked me if I would be willing to change those policies. I said yes. Tabs have always done it that way. But if you have a way of gathering that information without paying sources, if you have a way to do that, I’m fine with that. I think it’s something that’s very important to attracting reporters to the company right now.”

Pecker had already lowered the price they were willing to pay a source for a story on the reasoning that, with the tab market cornered, why should they pay $10,000 when they could pay $2,000?

But the lowered fees have dried up the flow of gossip to some degree, even as paparazzi photos get more expensive, thanks to all of the competition from more “legitimate” magazines—like Us.

Pecker is, according to a source at American Media, already in the micromanaging habit of moving articles around from tab to tab, often from the Enquirer to The Globe and The Star, which are more lightly staffed.

Making The Star into a magazine is one thing. Solving the problems at the other tabloids—The Globe, the Enquirer, the Weekly World News—is another. And that job may be about to get more difficult. Steve Coz, as respected a journalist as a National Enquirer editor can be, has taken two weeks off, and rumor in the company is that he may not return to report to Fuller. “As far as we know, he’s staying on,” says the company spokesperson. “She’s executive VP–editorial director for the whole company, Coz is executive VP–editorial director for the tabloids.” But people aren’t sure what’s going to happen next there: The tabs are in decline; when Evercore bought American Media for $837 million, they were already losing circulation and they’ve continued to lose. American may have a monopoly on the tabloids, having bought The Sun and The Globe. But the market for traditional tabloid fare is spreading thinner as more and more outlets are willing to cover it.

Fuller returns from Hawaii on July 7 and, says a company spokesperson, will begin her search for a new Star editor then. By remote control from Hawaii, she’s poached her assistant from Us, and made offers, according to word around the office, for the photo director and his No. 2. A play is also said to be in the works for “Hot Stuff” columnist Michael Lewittes. Janice Min, Fuller’s executive editor and to some degree her good cop, is said to be a lock for editor-in-chief of Us. Kent Brownridge throws down the gauntlet. “I would watch what happens to Us,” he says, “and watch what happens to The Star.”

One editor who worked with Fuller at Condé Nast neatly dissects her contradictions: “What she’s good at getting is women’s instantaneous superficial responses to things. What she gets caught up in knots about is where she fits in in life. She lives in this constant state of dissatisfaction, which is not a bad characteristic to have, but in her case, it means she moves jobs a lot.”

Newsstand flattens out, routine sets in. Corporate bosses start to micromanage. Time to go. Not that anyone forgets her. “We all have drinks sometimes,” says a former staffer. “We all consider ourselves survivors of Bonnie.”