After the election, New Yorkers may have joked about emigrating to Canada. But an unlikely group has been looking into Germany.

Article 116 of the 1949 German Constitution established a “right of return” for Jews who fled between 1933 and 1945, and their descendants. In 2002, the consulate in Manhattan processed only twenty Article 116 applications for citizenship. This year, “we had that many in one month,” says Friedo Sielemann, the consulate’s director of legal affairs. (Hardly a numeric groundswell, it’s true, but just think of the percentage increase.)

Requests started going up right before the election—ten in August, twelve in September, nineteen in October. Then, “on the day after the election, we had an unusual number of calls,” says press attaché Werner Schmidt. Much to his surprise: “Germany is usually a place you want to get away from.”

Consular officials are far too diplomatic to suggest a causal relationship between the uptick and Bush’s victory. “One could maybe go so far as to say they had the interest for many years and now they felt more of an urgency,” says Angela Terfloth, who assists applicants (the process normally takes around six months).

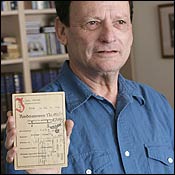

But some of the applicants are less guarded. “There are ways in which one can describe the U.S. as a fascist country,” says Michael Ochs, a retired editor whose family left Germany in 1939, when he was 2. He’s gathered up the necessary documents—including his old German passport, stamped with a large, red J—though he has no intention of moving back right away. He views it more as a precaution: “It’s very Jewish to want to know where the exit is.”

For retired history professor John Beer, who came here in 1937 at age 9, the decision to apply was motivated by his new religion, Quakerism. “My faith requires I forgive those who request it,” he says. “By accepting the German people’s offer for repatriation, I help them heal the hurt.”

Younger applicants tend to see a German passport more as a ticket to an EU identity. Rebecca, 26, a writer whose grandmother left Germany in the late thirties, has vague plans about living in Europe. “I don’t think it’d be Germany,” she quickly adds. But she may hold off on applying. The thought of telling her grandmother about her plans terrifies her (as evidenced by her request not to use her last name). “Most things I do in my life, she doesn’t need to know about. But this requires her birth certificate. I’m going to have to wait for her to die to apply.”