This much we know: The day that Marine Lieutenant Ilario Pantano killed the two men was like any other day in Iraq. It was a year ago, though no one could initially recall the date. The afternoon was drawing to a close. Soon, it would be dark. Already, 85 Americans had been killed that month, which would become the second deadliest of the war. To Pantano’s restless mind, all this had one meaning. “All of the conditions,” he thought, “are right for an ambush.”

Pantano is, in most every way, an unlikely Marine. He was a Manhattan preppy—his mother is a literary agent—who graduated from Horace Mann and New York University. He’d charged into Goldman Sachs, rising quickly, and then into a film company, the Shooting Gallery. If he set his sights on conquest, it seemed to be in the business world, as many ambitious New Yorkers did. And yet, it turned out that what he truly dreamed of was to be a warrior—a real one.

Now, a few weeks after arriving in Iraq, Pantano’s platoon had been dispatched to a dusty house along a dirt road near Mahmudiya, in the Sunni triangle. It was an ordinary house—one story, concrete. According to intelligence, it had been taken over by “Ali Baba,” as Pantano’s young Marines called the insurgents.

The intelligence seemed good, suspiciously good to Pantano. “My senses,” he’d write later, “were fully alert.”

At the scene, Pantano divided his platoon of 40 Marines. He sent a dozen to raid the house. The remainder dispersed, guarding his flanks. As Marines approached the target, a white sedan backed out and drove away. Pantano radioed that he’d take down the car. Pantano, 32, had with him a Navy medic, George Gobles, 21, whom everyone called Doc, and his new radio operator, Sergeant Daniel Coburn, 27.

Pantano yelled for the car to stop. When it didn’t, two warning shots were fired. The occupants, a man in his thirties or forties and another about 18, both wearing “man dresses,” as the Marines called them, finally stopped and raised their hands. They were unarmed.

Pantano received word from the Marines who’d taken the house. They’d found a modest cache of arms and also some significant items, including stakes used to aim mortars.

Pantano, who earlier had the Iraqis put in plastic handcuffs, now had Doc Gobles cut the cuffs off, which he did with his trauma shears. Then Gobles marched the two prisoners to their vehicle, placed one in the open door of the front seat, the other in the open door of the rear seat. Pantano motioned to the prisoners to search the car. He ordered Gobles to post security at the front of the car; Sergeant Coburn at the rear. Both men turned their backs on Pantano and the Iraqis.

A short time later, the shots started. Gobles and Coburn spun around. Pantano, ten feet from the Iraqis, emptied his M-16’s magazine, reloaded, emptied another. Later, Coburn recalled wondering “when the lieutenant was going to stop, because it was obvious that they were dead.” Photos, souvenirs taken by a Marine, would show one Iraqi nearly embracing the backseat of the car. The other lolled on his side, his head on the floorboard.

Coburn seemed distraught. He grabbed Gobles. “What the hell just happened?”

“Don’t worry,” Gobles said to settle him. “The blood is not on your hands.”

The first time I meet Ilario Pantano is at the Harrison, the restaurant he’s chosen in Tribeca. It’s dark and getting crowded, though floor-to-ceiling windows make it appear almost airy. It’s the kind of place a young trader might have liked after a day at Goldman Sachs. Pantano is six one, with a handsome face, angled like a cat’s, and a soldier’s telltale crew cut.

“How the fuck is this my life?” he says to me. It’s the question I have, too. Out of Horace Mann, Pantano had shocked his classmates by enlisting in the Marines. He’d gone off to the first Gulf War, though he hardly got to fire a shot. Then he returned to NYU and the acceptable prep-school trajectory, with jobs in investment banking, then media, before, prompted by 9/11, he rejoined.

Now he is facing the death penalty. Nearly a year after the killings, the military charged Pantano with two counts of premeditated murder. He is the only Marine who has served in Iraq to be charged with a capital crime.

The waitress arrives. “I desperately need a Tanqueray-and-tonic, please, like if it were on sale,” says Pantano, who, I know, isn’t much of a drinker. “Are you having a two-for-one sale? I’ll take three.”

Pantano says that he initially thought, okay, the military would do some fact-finding on the shootings. They’d talk to Doc Gobles and Sergeant Coburn, who has emerged as his principal accuser. They could interview anyone they wanted. No one had actually seen how the killings started but Pantano—the others had their backs turned. “And then,” Pantano says, “the neutron bomb was dropped, and I saw it’s … like, ‘You’re a fucking rogue animal, and we’re going to stomp you out,’ ” he says. “I was crushed.”

Before the incident, Pantano had been considered an “exceptionally qualified” Marine. “In the combat zone, there was no one better,” one captain said. Many who knew him in New York thought him “noble.” No one, and I talked to dozens, could believe him a murderer.

Pantano glances out the window. He doesn’t intend to go into details of the “incident,” as he calls it. “War is an ugly business,” he tells me. He offers another platitude: “The worst is that the energy expended on this is all energy that should be for CARE packages.”

Pantano pauses for a long moment. He’s wrangling a lot of emotion—he’s nauseous with it, he’ll tell me later. He can’t contain it.

“You’re trying to tell a warrior in combat that these guys are not sufficiently threatening?” he asks eventually. “The only way you can paint [this] picture [is] to say that we weren’t in combat, that we weren’t in the fight.”

There is a slightly belligerent edge in his tone—he was there, I wasn’t. Pantano says he acted in self-defense. Still, I wonder about reloading. Was that, too, self-defense?

He looks away for a moment. “The moral of the story is,” he says, “to a reporter from New York Magazine who’s never been in combat, or anyone who’s never been in combat, it seems excessive.” Pantano doesn’t say this meanly, or even pointedly. He seems almost sad—a breathless, inward sadness. This is his burden now.

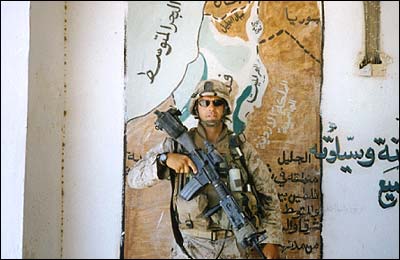

Pantano in a school east of Fallujah, 2004. (Photo Credit: Courtesy of Ilario Pantano)

It is a long way from the Harrison to an unpaved road outside Baghdad. Sitting in the restaurant, Pantano tries, for a second, to bridge the gap. “The threat is from everywhere and all the time,” he offers. He motions out the window, indicates across the street, as if to say, as close as the apartment with the flower box on the sill.

Dinner comes and goes. Pantano thinks about Coburn sometimes. He’d enlisted out of high school, he knows. Like Pantano, he was one of the few married guys in the platoon. As an infantry sergeant, he was marginal—“subpar” was the standard phrase. Pantano viewed him as in need of constant supervision, but not a bad person, not a bad Marine. Even now, Pantano supposes he got caught in “a dance that he may not have thought out all of the steps to.”

Then, momentarily, he entertains another thought. “Maybe I just don’t want to believe that somebody who is alive based on decisions I made, and not just on that date but others, many of them, would willfully subject me and my family to this,” he says. “I don’t think, I can’t believe—’cause that would be evil …”

It’s been four hours. “It gets to the point I don’t want to know, I can’t do it, I can’t,” he says. “So I have to take time away, I have to.”Tomorrow’s plan is to visit the new loft of his best friend from Horace Mann. Together, they’ll watch Battlestar Galactica—“the greatest show ever,” Pantano says—just as they did in high school.

Even as a child, Pantano stood out. Everyone noticed it. He grew up in Hell’s Kitchen—“the projects,” as one affluent friend put it—and attended Horace Mann on half-scholarship. “And paying half was a big sacrifice,” says his father, a gentle-mannered Italian immigrant who works as a freelance tourist guide.

At school, “I’d have this unbelievable, almost palatial retreat,” says Pantano, referring to the school’s eighteen verdant acres, its Gothic architecture. “And I’d come home in the afternoon and I’d get into fights with kids [with] knives, hammers.”

No wonder that as a child, Pantano dreamed about rescuers. He wanted to be Lancelot, knight of the Round Table. “He thought it was such an important job,” his aunt recalls. Then he wanted to be a samurai, practicing for hours with a sword. “There was something that was so powerful to me about being a protector of others,” Pantano says. It was a way, as he put it, “to order the chaos.”

Even at school, that unusual desire seemed to inform who he was. To hear classmates talk, it was as if a ship deposited a square, chivalrous Midwesterner in their midst. “He was that good guy who always did the right thing,” says a high-school friend. He was fun, transcended cliques, “didn’t lie,” says another friend, and also seemed instinctually patriotic. Did any other New York preppy hang an American flag on his bedroom wall?

He didn’t touch marijuana, telling a friend, “It’s illegal.” He dated one of the school’s prettiest girls—they snuck into clubs and danced all night. “He made me feel like Guinevere,” says Haley Fox, who now owns Alice’s Tea Cup on the Upper West Side.

In 1989, as his classmates packed for college, Pantano chose a different course. He’d never seemed particularly aggressive, not a fighter—he was in the drama club. Still, he’d long been obsessed with things military, read all about Vietnam, wore camouflage pants across the Riverdale campus, and once the Intrepid pulled into town, the gray old aircraft carrier became a virtual clubhouse. Now, on graduating from the elite high school, he enlisted in the Marines. “I would venture to say no one has ever enlisted in the Marines in the history of Horace Mann,” says a classmate.

Perhaps it was appealing to prove himself in a way none of his affluent classmates dared. The warrior was about discipline and deed; it was about “striving valiantly,” as his hero Teddy Roosevelt said, not inheriting it. His choice baffled friends. “The Marines—really, that was out there, crazy,” says his best friend from high school, Alexander Roy, who runs Europe by Car, a rental company. His father thought the same. To the Italian immigrant, the choice felt like a sad bit of class predetermination. Pantano’s father had few illusions about himself. “I am a moon,” he says. “My son is a sun. I wanted him to be a person of importance, what I never did.” The only way Pantano’s father could make sense of the decision was as a reaction to his parents’ recent separation. “A little punishment,” he says.

“No, Daddy,” Pantano told his father. “I want to be a Marine.” He explained, “The Marine Corps was the closest I could get to a knight.”

Pantano seemed immediately at ease in the company of aspiring warriors. “Traveling the world, shooting guns,” said his Marine buddy Jeff Dejessie. “We’re men; that’s what we’re meant to do.” Pantano brought to the Marines his overachieving ways. “If we had a run and had to score 280 to pick up rank, 99 percent of the people would just do enough,” says Dejessie. “Ilario would be sprinting like a maniac to get 300.” Pantano went to sniper school, one of the Marine Corps’ toughest.

During the first Gulf War, Pantano was part of an anti-tank platoon. He still remembers that the call to combat, when it finally came, made his bottom lip tremble so that he could hardly breathe. The ground war lasted just four days, and the Marines were greeted as liberators. “It was a safe war,” Pantano says. Still, he felt bullets whiz past his head and discovered that with fear came a pure, almost athletic thrill. “The feeling that somebody’s trying to kill you, but they’re not succeeding, but not for lack of trying,” he says, “there’s something about the complete sensory, the focus—it’s exhilarating.” His father says, “The greatest experience of his life was fighting a war.”

After his tour, Sergeant Pantano—impressively, he earned the rank in under four years—returned to New York, where he bartended at the Outback on 93rd Street while zipping through NYU. He often ran into former classmates, budding professionals, already perhaps a little doughy around the middle. They seemed awestruck. Said one, “He looked like he’d grown seven inches and was made of sculpted brass.” Life out of the Marines could seem paler. Pantano’s Marine buddies talked about it all the time. “You get back to mundane life, job, wife, girlfriend,” says Dejessie. “You miss that primal thing.”

Still, he had other priorities now. He was 22 when he left the Marines. “As a mature adult,” he says, “I had expectations that I had to live up to. And you can’t go backward. I needed to be moving forward, experiencing new things.”

Soon, he landed a job at Goldman Sachs, where he excelled. “He’s one of the most diligent people I’ve ever known,” says Chris Henwood, a trader who worked with him. Within a couple of years, he was an electricity trader, trading next-day delivery. “For a father, it’s a dream for a son to be in an environment like this,” says Pantano’s father. “Where he can make a future for himself.”

Yet, says Pantano, “I didn’t love the work.” You didn’t have to harbor rescue fantasies to appreciate the dismal state of the human project on a trading desk. Dumb grunts might be clueless in the world where fortunes are made; still, they dedicated themselves to a purpose beyond the next payday. “I thought Goldman would emulate the Marines’ sense of camaraderie,” says Pantano. “But you know, it’s a business.” No wonder Pantano always seemed to keep a Marine buddy close at hand, even if he didn’t always fit in. “When we all got out, I floundered around for a couple of years, working dead-end jobs, drinking, really doing nothing with myself,” remembers Dejessie. “Here’s Ilario, he had a lot of money and [was] just surrounded by all these powerful, beautiful people, and I’m driving into the city in my little car and I’m looking like a bum, unshaven, hair all messed up.”

One day, Dejessie took Pantano aside. “I really don’t fit in here. Why do you even bother with me?” he asked.

Pantano told Dejessie, “These people are my friends, they mean something to me, but they’d probably try and take my job in a minute. I trust you with my life.”

Pantano left Goldman at age 27. Soon, he landed a job as an executive vice-president of the Shooting Gallery, which had been started by some Horace Mann alums. A year later, he left to start his own business, Filter Media, which did strategic consulting on emerging technologies. Cablevision and Sony became clients. “He feels he can accomplish anything he sets his mind to,” says Vladimir Edelman, who’d left the Shooting Gallery with Pantano to start Filter.

“You’re not going,” she said. “You can’t go.”

He replied, “I love you and I want you to come with me,” he said. “but this is what I’ve got to do.”

On September 11, 2001, Ilario Pantano was on his way to a meeting, walking along Fifth Avenue near 28th Street. He had curly hair to his collar. He looked, as his fiancée, Jill Chapman, would put it, like “an edgy, hunky, downtown guy.” Soon after he saw the towers collapse, as if he were a sleeper cell remotely activated, he hurried to a barbershop. When he showed up at the apartment he shared with Jill, his head was shaved Marine style.

“I thought he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder,” she says.

The tragedy at the Trade Center changed everything. “For him, September 11 was too much,” his father says. Little about his life seemed to make sense anymore. On September 16, Jill learned she was pregnant.

A few days after that, Pantano told a friend, Damon D’Amore, now a producer for Mark Burnett, “Never again.” D’Amore, who keeps a photo of Pantano on his mantel, noticed the new tattoo on his forearm. USMC, it said, and under that, SCOUT SNIPER.

Over the next months, Pantano seemed unhappy. “I was scared I was going to lose him,” says Jill, by now his wife. Jill, a rebellious teen, had been a model—Robert Mapplethorpe shot her for Italian Vogue—who once liked to date punk-rockers. By the time she met Pantano, she was a merchandiser pushing 30, a contentedly self-centered Upper East Sider who wanted to raise a family, an upwardly mobile one, she’d hoped.

Pantano’s consulting business, though, no longer held his attention. Lately, he’d been thinking about the Marines. He was 30. He’d have to get an age waiver, and now a waiver for a dependent.

“You’re not going,” Jill pleaded. “You can’t go.”

Pantano sometimes explained his desire to serve in terms of his kid-to-be. “It’s about Daddy doing the right thing,” he said. “I don’t want someone else to fight my fight.”

Jill was pretty sure she’d never met anyone in the military. “If you’d told me I would end up married to a Marine, I would’ve said, ‘You’re on crack,’” she says. He sat her down. “If you want to be with me,” he said, “this is what I’ve got to do.” He wanted to rejoin, which meant uprooting her, cutting her income, leaving her for months at a time. “If you can’t understand that, sorry,” he said. “I love you, and I want you to come with me … I have to do this.”

“Warrior” might once have seemed a piece of teenage identity theater. It now felt like who he most wanted to be. “I always missed the Marines, always loved it,” he confessed. “September 11 gave me another chance.”

“I was not complete,” he told his wife.

“I fucking hate you, you son of a bitch,” Jill said when he told her, and then added, “You owe me.”

By nature, pantano was probably more intense than most Marines. Or, perhaps, he was just more than most—more intelligent, more articulate, more driven, more magnetic. If in New York he could seem the out-of-towner, in Iraq he played as very New York. “Flamboyant, passionate,” said one officer. Even in Iraq, he read the Sunday New York Times, which his mother mailed him. Given access to a TV in Iraq, Pantano switched on a fashion channel, offering running commentary. “It was almost like we were dealing with a celebrity,” said one Marine.

Pantano had trained to reenter the Marines at Crunch with 6 A.M. spin classes. During his officer’s-training course that led to, as Pantano put it, a Ph.D. in killology, he seemed an old man—at 31 he was the second oldest. But Pantano excelled. He was particularly good at making snap decisions on less-than-total information—and was voted the class leader. At one point, officers discussed what motivated Marines. Pantano was sure he knew. “Love,” he said, to everyone’s embarrassment. “The thing that gets you through the fight is the love of your brothers.”

Commissioned a second lieutenant, Pantano was assigned to command the third platoon of Easy Company, Second Battalion, Second Marines, one of the weaker platoons. Many of his 40 Marines were young, just months out of high school. To Pantano, they were “the most beautiful boys that you could imagine. You feel like you can be their father.”

“Warrior,” Pantano called them, or “War Hero,” and pushed them. “Force of will”—that’s what makes Marines, Pantano believes. He had them do push-ups while wearing gas masks to restrict their oxygen and simultaneously reciting phrases in Arabic. He’d purchased an Arabic CD and a copy of the Koran from Barnes & Noble—since their mission was to win hearts and minds. When they went to Iraq, in March 2004, a year after the fall of Baghdad, they expected to be like beat cops, forceful if trouble started but otherwise useful members of a community. Pantano familiarized them with the “wave tactic”—it meant waving to the population.

At the same time, most Marines noticed that in any threatening situation, Pantano had an extra setting. It wasn’t just that he was “passionate, thorough, dedicated,” as one officer explained, it was that he had these qualities “to a degree that’s almost unattainable by most people.” And his intensity rarely shut down. Said the officer who worked with Pantano: “If there was the most minute opportunity for danger, he would take every measure possible to eliminate that threat. He goes to the furthest extent to do the job right, and that’s something that I couldn’t say for anybody else.”

Pantano attempted to impart his outlook to his boys. “If you don’t pay attention,” he told them, then “somebody comes over that wall, [and] he’s going to kill you and me, and every fucking person in here, and the next time your mother sees you, you’re going to be laid out in a fucking pile of bodies with your fucking clothes stripped.”

Before they shipped out of Camp Lejeune, their home base in North Carolina, Pantano threw the platoon a party in the barracks lounge. Pantano bought beer, though some probably weren’t old enough to drink. Later, he’d promise their parents to bring them home safe. He’d also show them the HBO movie about September 11, to motivate them. “My duty, as is the duty of these other Marines,” he’d explain to the BBC, “is quite frankly to export violence to the four corners of the globe to make sure that this doesn’t happen again.” But that night, the order of business was camaraderie. Before they broke up, Pantano danced. He’d always been a wild, free dancer. He put 50 Cent on—“Fi-ty Cent!” his young Marines shouted. “The L.T. rolls to Fi-ty Cent!”—and made a corporal dance with him. His platoon appreciated his style. “We totally respect this guy,” said Lance Corporal Chris Johnson. “I think all of us do.”

Iraq would prove a challenging climate for Marine idealism—and not merely because the temperature reached 138 degrees. Pantano had a wave at the ready, candy in his pocket. He played soccer with Iraqi kids. There was no better salesman than Pantano—“People buy what he’s selling,” says a former business partner. Especially when he believes in the product. And when it came to American glory, Pantano was good to go. “If we can bring some comfort, some democracy, some opportunity,” he told a BBC crew in an unbroadcast interview in Iraq. “Maybe they won’t hate us so much.”

The Marine commander in Iraq, Major General James Mattis, echoed those sentiments, telling his troops that willing Iraqis would find “no better friend” than Marines. Of course, insurgent Iraqis could expect, as Mattis put it, “no worse enemy.”

It didn’t take long for Marines with any sense to concentrate on the enemy part. On March 31, 2004, news arrived about the four American contractors killed in Fallujah. Their mutilated bodies were dragged and then jubilantly hung from a bridge. The next day, Pantano’s platoon helped officially take control of the Sunni triangle.

Pantano playing with son Sandro in the backyard of their new home in North Carolina. (Photo Credit: Katy Grannan)

“I was an idealist until I started seeing our guys in bags,” says Pantano.

Ali Baba ambushed them constantly, fired mortars at their camps, and buried bombs by roads. Pantano’s platoon found a bomb at a girls’ elementary school, set to detonate at its opening ceremony. To add to the danger, you never knew which Iraqis to trust. “A lot of the people we ended up handing candy out to were, a couple of weeks later, shooting at us,” says Staff Sergeant Jason Glew, Pantano’s second-in-command.

One day, Pantano’s platoon visited Iraqis in the midst of building a mosque near Fallujah. The bricks had been paid for by American taxpayers. Still, a jeering kid flipped the finger at the departing Marines. “I’ll be seeing you, sweetheart,” a frustrated Pantano muttered to himself and patted his M-16.

On April 11, 2004, Easter Sunday, most of the platoon responded to the ambush of an Army convoy, their first time to pull the trigger. Fire came from two directions over a six-mile stretch of road. Pantano was horrified to see ambulances shot up by the enemy, dripping blood. Marines are trained to charge an ambush. “The only thing that will defeat aggression is more aggression,” Pantano says. “You can’t negotiate with someone trying to kill you. You have to kill them first.” It turned into a six-hour battle, with running firefights through the streets of Latifiyah.

Later, Pantano would tell New York friends, “Iraq makes Apocalypse Now look like day camp.”

When Pantano’s platoon had arrived in Iraq the previous month, Sergeant Coburn had been in charge of one of its three squads. “Coburn was a nice guy,” said Staff Sergeant Glew, the senior sergeant. Coburn had been a Marine for close to nine years, but leading men in war probably wasn’t what best suited his talents. “He seemed kind of weak,” said a squad member, who recalled Coburn being nonplussed at incoming mortars.

To Coburn, the problem was mainly a style issue. He didn’t like to yell. “In the infantry, you get looked down upon if you’re not a yeller,” says Coburn. Among officers, though, Coburn’s problem was also one of judgment. His performance was widely considered marginal—a company captain said it; other lieutenants in the company knew it. Sergeant Glew used the word “incompetent.” And Pantano hovered nearby, micromanaging.

“He’d always ask me,” says Coburn, referring to Pantano, “ ‘Hey, how you doing? You okay? Any problems?’ ”

Leave me alone! thought Coburn.

Listening to Pantano and Coburn, it could seem as if they were fighting in different wars. Coburn’s war, like his personality, was milder. “We’re over there to get them on our side, not to show our muscle and smack them around,” he says even today. “That was our mission: Go over there, shake hands, give candy to the kids, try to help out the Iraqi people.”

Coburn didn’t really get Pantano and his 9/11 fervor. “One of those thespian-type people,” Coburn says. To Coburn, it almost seemed that the enemy materialized only when Pantano was around, as if perhaps his zeal attracted them.

Coburn wasn’t entirely wrong. On patrol, Pantano would sometimes fire in the air to draw the enemy out, then fight his way back. “Often you’re walking a beat, getting hit, responding,” Pantano says. “In essence, [you have] to be the walking ambush … You almost ask to be attacked.”

Not Coburn. Coburn wasn’t in a firefight in Iraq. He doubted he’d killed anybody. He thought he fired his weapon once. “We were taking fire, and I just tried to aim at … tried to find a target to shoot at,” he says. “I just started shooting.”

One day on patrol, Coburn’s squad stopped for a break. There’d been enemy activity in the area. His guys were taking off their helmets within sight of unsearched buildings. “Men follow men into combat because they believe that they can keep them alive,” Pantano believes, and kind of flipped out. “Pantano is going to do it right,” explains one officer. “He has no sympathy for someone who’s not up there. He doesn’t take it easy on anybody.”

Pantano called the squad in. Why hadn’t Coburn posted security? Coburn told him the buildings had been checked yesterday. “You’re fucking fired,” Pantano recalls telling Coburn. “We’re parked in the middle of a kill box,” he told the squad. “It’s a miracle that we’re not all in a bag right now.”

Pantano and Sergeant Glew talked it over. “We could have very easily told the company commander he was incompetent as a sergeant and requested a reduction in rank,” says Glew. “We gave him the benefit of the doubt because he still gave his all, he still had good intentions.” So Coburn was reassigned. He might not be a warrior, an emasculating fact in this tribe; still, he was smart. He’d be the radio operator, tagging along with the medic and Pantano.

Coburn would later say that he was transferred to radio operator to help out with a platoon problem. “I went to the radio ’cause … I knew what I was doing on the radio,” Coburn says. “If I got fired … it didn’t sound like it to me.” But every Marine knows that radio operator is a job two or three pay grades below sergeant.

Toward 3 P.M. on April 15, 2004, a call summoned Pantano’s platoon to a modest house down a dirt road near Mahmudiya, which, according to intelligence reports, had been taken over by Ali Baba.

Dan Coburn with his sons, Nathan and Jason, in their backyard near Camp Lejeune. (Photo Credit: Katy Grannan)

The platoon responded in two seven-ton trucks and two Humvees. When a white sedan drove away, Pantano stopped it. With him were Doc Gobles and his new radio operator, Sergeant Coburn.

Over the next year, these three would write at least seven confidential accounts of the next few minutes, copies of which have been obtained by New York Magazine. All agree that Gobles initially searched the car.

It must have been near 6 P.M. when Pantano received a report on the contents of the house: mortar-aiming stakes, three AK-47s, ten AK magazines, assault vests, a flare gun, a box with Iraqi money, and wires that could perhaps be used in making bombs.

“Everybody has a few weapons,” said Coburn. Pantano didn’t see it that way. “It was clear that the two men were complicit in anti-coalition-force activities,” he wrote. At that point, Pantano ordered the men to be put in plastic handcuffs.

Pantano shifted into a more vigilant mode. To Coburn, this was a sign of trouble. “Lieutenant Pantano got mad,” Coburn wrote. He “started butt-stroking the car, breaking windows and lights, then walked around the car slashing all of the tires.” Coburn became convinced the two Iraqis, who claimed to be visiting relatives, would be released for lack of evidence.

Pantano denies saying anything to this effect, but in Coburn’s notion, this angered Pantano. “He had it in his mind that these were the people that were killing us,” says Coburn. Coburn paints a picture of a Pantano who “seemed a little pissed off,” who “seemed like he wanted to teach them a lesson.”

For Coburn, fresh from his own lesson at Pantano’s hands, this was hardly an unusual state for the lieutenant. In Coburn’s second statement, he recalls an example that he found revealing. “Pantano always told us that if we were to shoot the enemy Iraqi, we should do it to the point that it would send a message to everyone else,” wrote Coburn.

Pantano was certainly keyed up—from the start, he wrote, “my senses were fully alert”—but in his account, his actions were thought-out, methodical. Disabling an insurgent’s car, for instance, had become standard procedure for him.

Pantano told Gobles to cut off the cuffs. Other Marines used Iraqis to search their cars, though not usually after they’d been handcuffed. “My aim was to have them pull apart the seats so that [I] could verify if anything was hidden in them,” wrote Pantano.

To Coburn, this seemed suspicious. “[Doc] had already done a full search,” he wrote. To Pantano, the search had only been “cursory.” Gobles led the two Iraqis to the driver’s-side doors, and then Pantano directed Coburn and Gobles to post security, facing away from the vehicle. “As soon as I turned my back Lieutenant Pantano opened [fire] with approximately 45 rounds,” wrote Coburn. “Me and Doc Gobles were both shocked about what just happened.”

The two Iraqis were the first people Pantano had killed up close—probably the first that he could be certain he killed. Prosecutors would later interpret it as an execution. That’s why Pantano had the cuffs cut off and the soldiers face away. To Coburn, the storm of bullets reinforced that idea.

Pantano had thought about the incident often, which seemed, in his telling, an elaborately rational process. In Pantano’s account, the Iraqis were conferring while searching. Pantano told them to be quiet in Arabic—Gobles heard him do it. They didn’t. Their backs were to Pantano. “After another time of telling them to be quiet, they quickly pivoted their bodies toward each other,” he wrote. “They did this simultaneously, while still speaking in muffled Arabic. I thought they were attacking me.”

“Maybe I just don’t want to believe that someone who is alive based on decisions I made,” says Pantano, “would willfully subject me and my family to this.”

Pantano said that the two Iraqis kept moving after he started to fire, perhaps reacting to impact, which was one reason he continued to shoot, even in their backs.

There was another reason for all the firepower, which he says he decided while shooting. “I believed that by firing the number of rounds that I did, I was sending a message.” In case anyone missed the point, Pantano scrawled something on a piece of cardboard, which he wedged against the windshield. NO BETTER FRIEND, NO WORST ENEMY, it said. He meant the Marines. It was General Mattis’s motto.

Staff Sergeant Glew came running up to learn what happened. Glew later said Pantano told him that “he was instructing the locals to search the vehicle, and he said they lunged towards him.” Glew said that Pantano “just looked at me and said, ‘So I shot them. I’m not playing around with that.’”

“Roger that, sir,” said Glew. “Where are we going next?”

Coburn remembers that Marines walked off toward the target house. They joked about Pantano’s kill. “People are always happy when you kill someone,” says Coburn.

No one seemed to think much about the killings after that. Pantano led them on patrol—one time, Pantano barely escaped from a rooftop where he was pinned down by a sniper—and into the battle for Fallujah, where their excruciating training paid off. They ran out of Fallujah carrying 50 pounds of gear, gunshots at their backs. “We fucking ran forever,” remembered Lance Corporal Johnson.

Seven weeks later, Coburn mentioned the incident to a lance corporal who used to be in the company. Coburn’s captain later wondered why he hadn’t brought the matter to him. Maybe Coburn was concerned about the effect on the platoon, as he once said. Maybe, as he also said, “they”—the superior officers—“are all basically rooting for him”—Pantano—“so they would have squashed it right then and there.”

Over the next eight months, investigators hoped to exhume the bodies of the two Iraqis, who by now had names: Hamaady Kareem and Tahah Ahmead Hanjil. They were buried in a cemetery in Latifiyah, which proved too dangerous to reach. And so the investigation focused on testimony—increasingly, it seemed, on that of Doc Gobles, who’d make four written statements.

Pantano’s situation seems to inflict a special discomfort on the medic. He calls Pantano “a great leader and a great American.” Still, he feels uneasy. “There’re going to be things that are going be a little peculiar toward him,” he says.

For Gobles, the chief “peculiar thing” appears to be that he had searched the car twice before Pantano instructed the Iraqis to search it. His first was “hasty.” Still, it yielded, Gobles says, cans of wires and screws, “insurgent tools of the trade.” For Gobles’s second search, he removed the front and back seats, center console, and dashboard, none of which were bolted down, which alarmed Gobles.

Later, when Gobles posted security, his back to the vehicle, he watched “out of the corner of my eye.” He’d say he saw the guy in the front seat “rotate his head and upper body in the direction of” Pantano, consistent with Pantano’s account. Gobles concluded that he was trying to flee.

Clearly, investigators pushed Gobles, interviewing him four times in one month. Finally, they got Doc Gobles to say this: “I know for a fact that if I were in Lieutenant Pantano’s shoes under the same circumstances, I would not have fired at the Iraqis. I believe this was an unjustified shooting.”

Over the phone, though, he seems uncomfortable with that statement. “Well, maybe he”—Pantano—“could have butt-stroked them with his rifle or tried to tackle them or something,” Gobles explains from his barracks at Camp Lejeune. “But in that situation, it’s the man’s decision that is there at the time,” he adds. “Whether or not something could have been done differently, who’s to say that?”

In late June, Pantano was relieved of his platoon command and reassigned to an operations center. Pantano recalls his first day at his new post was Father’s Day 2004. On the radio, he heard that a squad from his platoon was getting hit. Lance Corporal Johnson, the one who said how everyone respected Pantano, was in a Humvee. A bullet pierced the side; shrapnel got him in the arm, the platoon’s first serious casualty. (He’d lose the arm. “Just cut the darn shit off and be on my way,” he’d tell the doctors.)

Pantano followed on the radio as events unfolded. “It was my worst moment in the whole war,” Pantano said later, “knowing that they were in trouble and that I was not there. I had sworn to take care of them, and there was nothing I could do. I felt like I had betrayed my men.”

Sergeant Daniel L. Coburn lives with his wife, Rae Anne, in Jacksonville, North Carolina, home to Camp Lejeune. Near the Marine base, the second largest in the country, Jacksonville seems to be either a giant going-out-of-business sale (pawnshops advertise WE BUY DRESS BLUES) or a low-end men’s club (tattoo parlors, gun stores, barbershops, and strip bars, one of which proclaims, WE SUPPORT OUR TROOPS, OPEN AT NOON).

The Coburns live a fifteen-minute drive from the base, down a shady cul-de-sac. The evening I arrive, unannounced, Rae Anne’s babysitting charges are just leaving. The front door is open. One of the kids ushers me in. Coburn has, like everyone else, been ordered not to talk to the press. Pantano’s lawyer, though, has labeled him “a disgruntled employee,” as if this whole thing is small-minded office politics. It irks Coburn, and it irks Rae Anne, who knows her husband to be a sweet man. “Do we look disgruntled?” she asks impishly. She smiles. She holds their newest child, a 5-month-old son born just six days before the platoon returned from Iraq last October. Coburn is in his work uniform, camouflage pants, boots, green T-shirt with sergeant’s stripes on it.

In the living room, there’s an old comfortable blue couch, pale worn carpet. The TV is on. American Idol will be up soon. They’ve been looking forward to it all week.

This is their dream house. They moved in a few months ago. It needs work, but they’re happy to do it. It’s a house to grow in, room enough for their three kids, plus the one more they’d like to have, if everything goes okay. They’re nervous. Coburn, who’s from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, has been in for nearly ten years. They make do on his sergeant’s salary, not quite $30,000 a year, including allowances, plus Rae Anne’s babysitting. They hope Coburn’s pay increases as he moves up in rank. If he moves up in rank.

Coburn has a pretty clear idea of himself. He’d like to transfer out of the infantry. He prefers to work on his own—“something that will complement my personality better,” he says. He wants the kind of job where, as he put it, “nobody’s going, ‘I want this done now.’ ” Coburn prefers a job where, as he explained, “I’m doing something because I want to do it. I don’t like to be told to do something when I’m already doing something.”

Standing in Coburn’s way are two negative evaluations of him initially written by Pantano. One covers a period before the incident. Another, the more severe, was written after. “In the unforgiving classroom of combat operations he was extended myriad opportunities to learn and to grow,” says that second evaluation. “Instead of developing, the opposite occurred and now he is solely responsible for managing the radio.”

Coburn sits straight as a chair. “It’s a career-ender,” he says. Coburn is trying to get the bad paper—both of the evaluations—removed from his file, which is possible, particularly if the judgment of the officer doing the evaluation or the circumstances surrounding it are in question. “They’re saying things about me that aren’t true,” Coburn says. “They all think that I’m the guy with a grudge on my shoulder,” says Coburn. “I got fired so I’m blaming him for something that didn’t happen. Whatever.”

He might have to hire a lawyer. He’d rather not. They’ve been saving for new windows. The lawyer money, he says, “that’s my windows.” Coburn’s 3-year-old climbs onto his lap. She wants something to eat. He shoos her sergeant-style, mock-gruff, which she ignores, continuing her singsongy complaint.

Lieutenant Ilario Pantano lives an hour south of Camp Lejeune, in Wilmington, North Carolina, a beachy suburb that Forbes called one of America’s best places to live and work. Pantano and his wife also live in their “dream house,” as Jill calls it. They moved in a few weeks ago. Pantano earns $50,018.40 a year, one of the odd details listed on the sheet charging him with murder. That won’t buy much New York real estate. But values are better in North Carolina, and they’ve been able to add some touches, like marble countertops in the kitchen, and also blast-proofing on all the windows.

Jill says it makes the place gloomier, but Pantano insisted. With all that’s going on—a Website out of Pakistan threatened his life—Pantano has gone on high alert. He installed triple redundant alarms with movement sensors, and he stocks an aggressive-looking weapon in most rooms. In their bedroom closet, there’s an M-4 rifle near a bag from the Chanel store. It makes Pantano feel better. “Like I’m doing something,” he says. “Like I’m in the fight.”

Jill is still a New Yorker, and still thinks about Manhattan. “We had a cushy life there,” she says. When she talks to her New York friends, they let her know they wouldn’t be able to handle her new life.

“What choice do I have?” she tells them.

We head to the backyard. Pantano hunts up cigars, those his father sent him in Iraq. Outside, the air is chilly. Beyond a row of azaleas is a wood-slat fence and then trees as far as you can see. It’s isolated here, almost lonely, the way the suburbs always are. It makes me think of something Pantano said about the killings. “It’s kind of weird—I did feel like I was alone,” he’d said.

Killing seems a hyperrational process now, all those pages written on the events of a minute or two. And yet, as Pantano once told me, “When you’re really in the shit, your brain is mush and some inner primal part of you kicks in.”

In a way, none of it matters. We sit in the dark, so still that Pantano’s motion detectors don’t kick in. The lights stay off. Jill smokes Marlboro Lights; she’s started again.

“You’re still here,” Pantano tells her.

“Well, I still love you,” she says, as if it might be involuntary. “I think actually our relationship is a lot stronger now.”

Some people close to Pantano say that all he wants is to return to the fight. Occasionally, Pantano even imagines a call from General Mattis himself: “Warrior, this is a fucking horrendous mistake and you’re good to go.” Pantano knows he will have to wait for his court-martial to see Mattis, who is on his witness list.

Even if he beats the charges, Pantano’s military career is finished. “Regardless of whether this thing goes away tomorrow,” he says, “the rest of my life has changed irrevocably.” The project now is to get through this, the humiliation, the betrayal, the threat. “I understand who this man is that’s done these things,” Pantano told me. “I understand how the world works. I’m certainly not naïve. Now there’s a machine working to get a conviction regardless of what the realities are.”

As a boy in a two-bedroom apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, he’d longed to be Lancelot. Now, he says, “I’m just trying to fucking shut these things down,” he says, though sometimes, he adds, “I can hardly fucking concentrate, I can hardly fucking see.”

A few stars are out, though the woods behind the property are impenetrable. Suddenly, Pantano gets up, walks toward the fence. “He heard a noise,” Jill says. And so Second Lieutenant Pantano, his battalion’s best, moves to the perimeter, stares into the dark woods, scouting for the enemy.