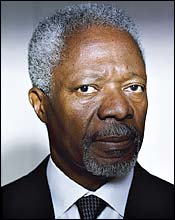

Kofi Annan is sitting in his private dining room on the 38th floor of the United Nations Building, sipping a glass of red wine at lunch. He sounds hurt and angry as he talks about the “lynch mob” out to “destroy” him. It’s Monday, March 28, the day before the scheduled release of the second of three reports from the Volcker commission, the panel investigating Annan and his son, Kojo, for their role in the U.N. oil-for-food debacle. The pressure the 67-year-old U.N. secretary-general has been under since the scandal broke has been so withering—Annan has been blistered by conservative pundits, and Republican congressmen have called for his resignation—that he’s discussed quitting with close friends and his wife, Nane. “I’ve thought about it,” he says. “Resignation is the easy path. Nane and I could have a wonderful life, travel, sit on the farm I dream about.” A weary smile plays on his face. “No one is indispensable.”

The secretary-general had spent much of his weekend at his official residence, a sprawling brick mansion on Sutton Place, working and bracing for a difficult week ahead. Annan had been given a partial advance summary of the Volcker commission’s findings, which amounted to a slap on the wrist but found no evidence that Annan steered a lucrative oil-for-food contract to a company that employed Kojo. Still, the preliminary report criticized Annan for lax oversight, and word was that the final version would excoriate Kojo for significant improprieties. Annan called French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac to discuss the situation in Lebanon. He spoke with the family of Rafik Hariri, the former Lebanese prime minister who was assassinated in February. He and Nane, who have significantly cut back on their once-busy social life, had a quiet dinner with Ted Sorensen, the former JFK speechwriter, and his wife, Gillian, a former U.N. staffer. On Sunday, Annan huddled with his lawyer, Gregory Craig, and his chief of staff, Mark Malloch Brown, to draft a response to be included with the Volcker report. Although the Annans attend church occasionally (he’s Anglican, she’s Lutheran), this Sunday—Easter Sunday—was not a day when they wanted to say their prayers in public. Instead, they went for a walk in Central Park and watched The King and I.

Kojo had called Annan during the weekend. Annan had learned in November that his son had misled him about his unsavory financial dealings. “He has apologized,” Annan says. “He is extremely embarrassed.” Yet their discussions continue to be a tug-of-war: “I’ve talked to him about coming clean with everything he knows, no surprises,” Annan says. But Kojo, who has refused to meet with investigators since October or to turn over additional documents, held firm.

In the U.N. dining room, on a day when thick clouds obscure the normally sparkling view of the city, Annan sounds baffled as he tries to grasp the magnitude of his son’s deceit. “I have no theories. You know, it’s incredible when you see these little children. You carry them in your arms and lead them along the way. And over time, they develop their own personalities and become their own person.” He stops, then adds quietly, “Of course, he maintains he did nothing wrong.” Even now? I ask. “Yes, now.” It’s hard to fathom just how far Kofi Annan has fallen. Elected U.N. secretary-general in December 1996, he instantly became the rarest of things: an international diplomatic rock star. Fawning profiles invariably noted his noble African ancestry, soft-spoken charisma, and sterling reputation for honesty (even criticism that Annan had acted too slowly to stop the Rwandan genocide in his previous position as head of U.N. Peacekeeping didn’t tarnish his star). The Clinton administration crusaded for Annan’s ascendancy, citing his deft diplomatic skills and moral authority, and world leaders from diverse nations saw him as their champion. In his first term, he made fighting AIDS a global priority, promoted a measure to allow the international community to step in when countries can’t protect their own people, and even got Senator Jesse Helms to release nearly $1 billion to pay the backlog of American U.N. dues. Annan and Nane (the niece of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who saved thousands of Hungarian Jews during the Holocaust) became the toast of Washington and New York, socializing with Brooke Astor, Oscar de La Renta, and Tom Brokaw. “They’re an extraordinary couple,” observes author Kati Marton, a close friend. “I don’t think people were falling over themselves to wine and dine Mr. and Mrs. Boutros Boutros-Ghali.”

Annan was unanimously reelected in 2001 to a second five-year term, and his career peaked when he won the Nobel Peace Prize that December for his efforts to bring new life to the beleaguered U.N. Footage of the award ceremony in Oslo shows a beaming Kojo at his father’s side. “Kofi had the quiet charisma and the respect of most of the world, and the Nobel Prize was the high point,” recalls Richard Holbrooke, the former American ambassador to the U.N. (and Marton’s husband), who attended the event. “The night before the ceremony, he looked out from a balcony at a crowd holding candles in the street below. It was an extraordinary moment.”

It was one of Annan’s last good moments to date. The U.S. decision to invade Iraq without U.N. consent created the biggest rift between the U.N. and the U.S. in decades, and left Annan, a fierce war opponent, politically hobbled. In August 2003, 22 of Annan’s colleagues, including the U.N. special representative Sergio Vieira de Mello, one of Annan’s closest friends, were killed in the bombing of U.N. headquarters in Baghdad. The oil-for-food scandal has not only raised questions about Annan’s integrity and competence as a manager, but also embarrassed him—and caused him tremendous pain—as a father. Aides have been accused of unethical behavior, U.N. peacekeepers in the Congo have been charged with sexually abusing minors, and a Swiss investigation was launched recently into whether bribes were paid to renovate a United Nations building in Geneva. In March, the Bush administration nominated John Bolton, a fire-breathing conservative and one of the U.N.’s most outspoken critics, as the U.S. ambassador to the U.N.—a straight jab at Annan and the international body.

Five separate congressional committees are currently holding hearings on the oil-for-food program and other U.N. mismanagement issues, and Capitol Hill Republicans are screaming for Annan’s resignation. “He’s headed up a scandal-ridden and broken organization,” says right-wing California congressman Dana Rohrabacher, the chair of one investigation. “The U.N.’s ability to do its job has been tarnished.”

Most diplomats who visit Annan’s office these days begin by referring, obliquely, to his troubles by offering comforting words. Paulette Bethel of the Bahamas recently led off a session with two other ambassadors by saying, “We’d like to reaffirm our support for you.” But Nile Gardiner, a conservative U.N. critic with the Heritage Foundation, insists some of the declarations are hypocritical. “Many countries are expressing their support, but they smell blood in the water. They’re maneuvering to get someone into his job.”

“This is an organization under siege,” says Annan spokesman Fred Eckhard, who’s become a human punching bag for the press. “You go out there every day and get wiped out.” “We’re human,” adds Kevin Kennedy, Annan’s chief of scheduling. “It affects morale.”The litany of woes Annan has endured has not only weakened the U.N. and damaged his career but it’s left him personally shaken as well, especially regarding Kojo. “I’m suffering on various levels,” he says. “As a secretary-general, and as a father dealing with his son. It’s all heavy and difficult.”

For a man who is only five seven, Annan has long been seen as a leader with a commanding presence. He joined the U.N. in 1962, and he’s the first secretary-general to rise through the ranks. He’s never been a table-pounder, he doesn’t swear (“Oh, gosh” is about as vitriolic as he gets), and his diplomatic style is to listen thoughtfully and play the conciliator. “He doesn’t like confrontation,” says British Ambassador Emyr Jones Parry. “He becomes quite distant.”The multiple crises have changed him. Annan was vibrating with tension on the first day I met with him at his office, on a Friday morning in early February, to discuss whether he would cooperate with this story. It was admittedly a difficult day: He was in the process of ousting Ruud Lubbers, the head of the U.N. Human Rights Commission accused of sexually harassing staffers (more on that below), and Lubbers was scheduled to arrive within the hour. But for a man renowned for his personal charm and ability to remain calm under pressure, Annan came across as wary and abrupt. I had scarcely made my pitch when a secretary handed Annan a note to say that John Negroponte, the former American ambassador to the U.N. and new U.S. intelligence czar, was on his way down the hall; Annan hustled me out.

Annan’s emotions fluctuated visibly during the next six weeks as I sat in on a half-dozen meetings with him, from discussions over how to end the massacres in Darfur to talks about a sweeping U.N. reform package. Annan was edgy and strained some days, engaged and astute on others. The overall impression he left was that of a man at the center of a maelstrom, coping by the hour.

“I’m suffering on various levels,” says Annan. “As a secretary-general, and as a father dealing with his son.”

About the only time Annan seemed happy was in the presence of his wife. At his office one day, midway through a conversation, he picked up the phone and invited Nane, who was in an anteroom, to meet me. Annan and Nane have been married twenty years and are extremely close. Nane, a lawyer turned painter, is a slim and stylish blonde. Making small talk, I asked whether any of the paintings in the room were by her, and she demurred that her works aren’t worthy. “I’m the world’s most famous non-famous artist,” she said. Then she walked over to the window and pointed toward Brooklyn. “I used to have a studio there,” she said. She was referring to the period before her husband became secretary-general and her duties as his wife took so much of her time.

When the Iraq war began in March 2003, Annan had a striking personal reaction: He lost his voice. Doctors performed tests, found nothing wrong, and diagnosed stress. “It was completely psychosomatic,” says a staffer. Annan was ordered to limit his speaking and had to cancel appointments for weeks. In the two years since, he’s been vulnerable to similar attacks. Sometimes he whispers his way through meetings; his bodyguards keep Halls cough drops at the ready.

On August 19, 2003, a suicide bomber blew up a cement mixer packed with explosives in front of the U.N. building in Baghdad, killing Vieira de Mello and 21 others. Annan still agonizes over the deaths. “To have done everything I could to help avoid this war,” he says, “which could have been avoided, and sending these wonderful people to help, and they get blown away. You know their wives, their sons. You feel responsible for their lives.”

Annan didn’t start the oil-for-food program—it was launched under Boutros-Ghali in 1996—but the program continued under his watch. U.N. trade sanctions had choked the Iraqi economy, so the Security Council allowed Saddam to sell oil to purchase food and medical supplies under U.N. auspices. Saddam manipulated the program to loot billions, smuggling in weapons and paying kickbacks to win international favors. “The U.N. had never administered a program of this nature, and they didn’t know how to do it,” says Pakistani ambassador Munir Akram. Member nations weren’t eager to look closely at the program, Akram says, since countries were busily pushing to make sure their banks and local corporations got a piece of the action. “There was a permissive atmosphere in the council,” he says. “It was not a well-kept secret.”

The first time Annan realized he might have a personal problem with the oil-for-food program came as far back as January 24, 1999, when the London Sunday Telegraph ran a story with the headline FURY AT ANNAN SON’S LINK TO £6M U.N. DEAL. The story questioned whether nepotism played a role in helping Cotecna, a Swiss company that employed Kojo Annan, to win a lucrative U.N. contract to inspect oil-for-food shipments. Annan says he was stunned by the news, and was unaware that Cotecna was angling for the contract, since he didn’t supervise bidding. Annan immediately asked that the charge be investigated, but the in-house inquiry he ordered ended after one day, after concluding that Cotecna won because it was the low bidder. Kojo insisted he had done nothing wrong, and told his father that he had severed his relationship with Cotecna on December 31, 1998 (according to the Volcker report, Kojo actually stayed on the payroll through February 2004). The Volcker commission would later conclude that Annan was derelict in not pursuing a more vigorous investigation of Cotecna since the company was already under an ethical cloud for other business dealings.

The Wall Street Journal’s news section published a major investigation of the oil-for-food program on May 2, 2002, charging that Saddam had siphoned money from the program for his war chest and that U.N. auditors were lax. Annan’s name wasn’t mentioned, but shortly after Bush went before the U.N. General Assembly in September 2002 to make the case for going to war, Claudia Rosett, a commentator writing on the Journal’s editorial page, led a two-barreled attack on Annan for being a “ditherer” over the war and ethically tarnished in presiding over the oil-for-food program. After major combat in Iraq ended, other conservatives, including William Safire, began focusing on the oil-for-food program as well.

Annan took a very long time to respond, suggesting, to his critics, that he didn’t take the matter seriously. It wasn’t until April 2004 that Annan named an independent commission, led by former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, to investigate oil-for-food, with a freewheeling mandate to look at the questionable behavior of U.N. officials monitoring the program, examine whether Security Council members were aware of the corruption, and take a hard look at his own and Kojo’s roles.

The secretary-general was so convinced that he had nothing to hide that he didn’t initially hire a personal attorney—he met with investigators twice without legal advice before friends intervened.

The criticism of Annan grew louder last year even as the Volcker commission began its work, but the complaints primarily focused on his handling of other issues. Whether preoccupied by the inquiry or haunted by the deaths of his colleagues in Iraq, Annan seemed to have lost his once-vaunted political instincts.

As a longtime U.N. bureaucrat, Annan has always had a reputation for being reluctant to fire employees and for being extremely loyal; mention the latter quality now and he interrupts to say, “Loyal to a fault?” That is, indeed, the rap. Ruud Lubbers, the U.N.’s high commissioner for Refugees, was accused of groping several women in December 2003, and investigators found the complaints valid. But Annan consulted outside lawyers who concluded that the U.N.’s internal investigation wouldn’t hold up in court. He officially cleared Lubbers in July, a decision that sent shock waves through the organization, essentially conveying the message that Annan, the renowned human-rights champion, was a member of the old-boys’ club. “Kofi didn’t go back to the investigators and say, ‘Get more goods, you haven’t made your case,’ ” says one high-ranking staffer. An Annan pal says bluntly, “He should have just fired the guy.” Only this winter, when newspapers printed the affidavits describing Lubbers’s boorish behavior, did Annan force Lubbers out.

Another sign that Annan’s political judgment was out of whack came on the Sunday before the November 2, 2004, presidential election, when he sent letters to the U.S., Great Britain, and Iraq, urging the countries not to send forces to go after rebels in Fallujah. “We were thunderstruck,” says a senior American official. “It was hard to see this as anything but an effort to interfere with the electoral process.” Annan insists that he wasn’t trying to tilt the election toward John Kerry, but he admits that the Fallujah letter was a mistake: “In retrospect, maybe the timing was not the best.”

The dark atmosphere at the U.N. grew darker after Bush’s reelection, as congressional committees investigating the oil-for-food scandal began to churn up information about Saddam’s looting. “There were weeks when Kofi seemed disturbed, bothered, unfocused,” says a prominent diplomat and Annan backer. Annan became increasingly worried and withdrawn. Staffers and diplomats grumbled that it took forever for him to make decisions.

In December, in the diplomatic equivalent of a substance-abuse intervention, Annan sat through two separate confrontational meetings (the first with top staffers at the home of Deputy Secretary-General Louise Fréchette and the second with friends and informal advisers at Holbrooke’s Central Park West apartment) as people told him in excruciating detail all the ways in which he was screwing up. Annan was urged to make amends with Washington, clean house, and be more forceful in his leadership.

At the same time, the secretary-general’s heartbreak over Kojo was intensifying. Annan got a call from Fred Eckhard, telling him that, according to news reports, Kojo had deceived him; the Cotecna checks had kept coming for years. “It hit him like a rock,” said an aide who was with Annan when he got the news. Senator Norm Coleman, a Minnesota Republican, promptly demanded Annan’s resignation. “I was taken aback and puzzled,” Annan says, in a soft voice. He called Kojo, and a series of angry father-son conversations ensued. The Volcker report subsequently revealed that, according to Kojo’s financial records, Kojo conspired to hide the payments by disguising them as money wired to him from three separate companies and other sources, a sum estimated to be about $400,000.

Annan received more bad news in December. The Volcker commission was also quizzing his chief of staff, Iqbal Riza, about shredding documents. Riza insisted to Annan and the commission that the documents were duplicates—that he’d agreed to the shredding after secretaries complained their files were full. The news of the shredding wouldn’t become public until the Volcker report came out in March, but Annan knew that the revelation would be damaging. Did he worry that everyone would think “cover-up”? “Exactly,” he says. “Cover-up, and remember the eight minutes in the Nixon tapes.” Annan decided to purge his staff in late December, sending Riza, 70, into retirement, getting rid of many of his closest advisers, and bringing in Mark Malloch Brown, the forceful and witty British head of the U.N. Development Program and a former political spinmeister, as his new chief of staff.

Still, Annan couldn’t shake the blues this winter. It’s been an open secret for months in the U.N. that he has been melancholy and unable to hide his distress. “He’s put on a brave front and tried to soldier on,” says Pakistani ambassador Akram. “He’s been under pressure for so long. It affects his mood.” The entire diplomatic community and staffers, it seems, have been swapping stories about how distracted Annan has been. After Annan met with Tony Blair and Condoleezza Rice in London in March, word spread quickly that he had stumbled over his talking points, an embarrassing and uncharacteristic faux pas. His every gesture is under a microscope, from the slump of his usually erect shoulders to each nuance of his body language. “Watch his hands,” says a sympathetic ambassador. “The more nervous he gets, the more his hands are all over the place. They betray him.”

This winter, Annan and Nane stopped hosting what were once regular parties at their home, and have turned down virtually all the invitations they receive. “I’m not in the mood for socializing,” he says.

Tell Annan that friends and colleagues worry that he seems depressed, and he doesn’t deny it. “There hasn’t been too much to laugh about,” he says. “There have been those difficult periods when you wonder, What’s it all about and where are we going? I’ve been under pressure for, how many years now? Almost fifteen years, going back to my background in the Department of Peacekeeping. I can handle the pressure, but certain things touch you.”

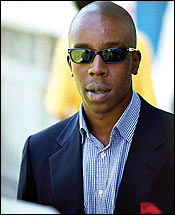

Kofi Annan married Titi Alakija, a Nigerian woman from a well-to-do family, in 1965. A few years later they had a daughter, Ama, now 35, followed by a son, Kojo, now 31.

A friend recalls that there was “trouble” relatively early in the marriage, remembering a vacation when the couple opted for separate quarters. Still, Kofi and Titi stayed together for many years, through a number of Annan’s career moves—to a U.N. job in New York, a posting in Ethiopia, a year at MIT for a master’s degree in management, a career detour back to his native Ghana where he managed the state tourism agency, and a return to the U.N. in Geneva, to work at the High Commission on Refugees.

The couple separated in the late seventies, but Annan remained an involved parent. “Kojo lived with his father for a while; Kofi did everything for him,” says Julia Preiswerk, a Geneva psychoanalyst who has known Annan for four decades and remains a close friend. Shashi Tharoor, now the U.N. undersecretary-general for communications, who worked with Annan in Geneva, says, “He had this rule that he’d leave work to pick up the kids at school and bring them home and then come back to the office.” Annan was proud that his young son saw him as a nurturing figure. Tharoor adds, “One story he told was how Kojo said, ‘Dad, I want you to come to this event at school,’ and Kofi said, ‘I can’t, I have an official commitment.’ And Kojo said, ‘But all the other mothers will be there.’”

Annan had been living apart from his wife for several years when in 1981 he fell in love with Nane Lagergren, a beautiful and accomplished lawyer working at the U.N., who was divorced with a young daughter, Nina, from her first marriage. But the couple never entirely blended their families. Around the time Annan learned he was being transferred by the U.N. to New York, the first Mrs. Annan moved from Geneva to London, and the Annan children were sent to boarding school in England. Ama was 12 and Kojo was 9. (Annan married Nane in 1984.)

It’s been an open secret at the U.N. that Annan has been melancholy and unable to hide his distress.

Annan clearly wonders now about the impact of that early separation on his son, but it didn’t seem unduly wrenching at the time. “I got used to taking decisions for myself very early, from when I went to boarding school,” Kofi said. “Kojo went to boarding school early. He came on holidays.”

The family relationships played out mostly over weekly phone calls and summer vacations. It was a jet-setting life—the children also spent time in Nigeria, their mother’s homeland. Still, Kojo seemed like a happy-go-lucky kid. He was outgoing and a star rugby player at his British boarding school; father and son would see rugby games together and watch them on TV. (Kojo did not respond to several requests for an interview, sent via his London lawyer, Clarissa Amato.) As a teenager, Kojo spent a summer living with his father and stepmother on Roosevelt Island, working as an intern for fund-raiser and family friend Toni Goodale. “We loved him around the office,” says Goodale. “He was a delight—terrific personality, outgoing, funny.”

After graduating from Keele University, Kojo wangled a job in September 1995 at Cotecna through a family friend and was stationed in Lagos, Nigeria, as a junior liaison officer. According to the Volcker report, the company hoped to exploit his family connections. Indeed, Kojo ultimately arranged for his father to meet Cotecna chairman Elie Massey. (The report found no evidence that Annan and Massey discussed the oil-for-food contract.) After two years with Cotecna, Kojo resigned as an employee, but signed on as a consultant.

From that point on, Kojo went all out in using the Annan name to make money, according to the Volcker report. He met with an Iraqi ambassador in Lagos to inquire about business opportunities, visited his father in New York during General Assembly meetings, and talked up the virtues of Cotecna to African diplomats.

If Kojo was rebelling against his father, or was angry over the divorce, it wasn’t apparent. “I’ve never seen any problems or tension between Kofi and Kojo,” says Goodale, who has been hosting a family Christmas dinner at her Upper East Side home with the secretary-general and his children for many years. “Kofi would glow when he talked about Kojo and Ama. Kojo made his father laugh.”

Annan, an indulgent father and by nature nonconfrontational, remains baffled about Kojo’s motives. “I’ve always lived quite a straight life,” he says. “I’m not one of those who is in a hurry to get rich. It’s not my way of life or desire.”

In the Annans’ official residence, the large red-brick mansion on Sutton Place, Nane Annan joins me in the second-floor library, a handsome wood-paneled room decorated with an Oriental rug, stacks of art books, and African masks and sculpture. Her blonde hair is pulled back in a bun, emphasizing the worry lines around her eyes, and she speaks in a lilting Scandinavian accent, her voice often drifting off mid-sentence.

“It’s not been easy,” she begins, reciting the sad series of events of the past few years. She tells me she’s been accompanying her husband on recent trips. “I try to provide a home away from home, to have somebody, to hold hands and sit together,” she says. “All the things that are not official, that are between two people who love each other.”

Mention Kojo, and she flinches, breaking eye contact to stare at the coffee table. The conversation stops—so I ask what Kofi has been like as a parent. “I think he’s been a caring father,” she says, cautiously. “Of course, this is very painful to him as a father and a secretary-general. It’s difficult, it’s difficult,” she says. “This is so unfortunate.”

Nane has maintained a full schedule, speaking at a reception for women with AIDS, attending an award ceremony for the king of Jordan. But friends say she’s counting the days until her husband’s time at the U.N. is over. The couple hasn’t yet made plans for the future, even though they’ve always known his second term would end in December 2006. They’ve had conversations about purchasing a farm in Ghana and a home in Europe, but it’s all quite abstract. As Nane says, with a bleak look on her face, “We are living in the present.”

On the afternoon of March 29, hours after part two of the Volcker report was released, Annan walked into the press room downstairs, flash bulbs popping. He read a brief statement expressing relief at his “exoneration,” and took just three questions. The final one was the zinger: “Do you feel it’s time for the good of the organization to step down?” Looking straight at the TV cameras, Annan delivered the line that would define the news coverage of the day: “Hell, no.”

For all Annan’s bravado, the reaction to the report was resoundingly negative. Norm Coleman reiterated his call for Annan’s resignation, and more newspaper editorials ripped into him. Mark Pieth, a member of the Volcker panel, challenged Annan’s defiant comment by saying, “We did not exonerate Kofi Annan … A certain mea culpa would have been appropriate.” (Two investigators on the panel have since resigned in protest, apparently because they believe Annan has been treated too gently.)

Still, Annan seems likely to hold onto his job—important members of the Security Council are stoutly behind him. “Kofi enjoys the full support of the British government,” says British ambassador Jones Parry. France’s Jean-Marc De la Sabliere is equally unequivocal: “Kofi is a man of principle. We are supporting him.” Influential Israeli Ambassador Dan Gillerman adds, “He has weathered the eye of the storm, and has come through maybe scarred, but with his integrity in place and able to carry on.”

The final Volcker report is due out this summer. Insiders say that Annan is no longer under investigation for personal ethical lapses, but that doesn’t mean he’s in the clear. “To the extent that he’s the guy at the top, that’s where the buck stops,” says a source. “The thing that’s going to get to him is the kid.” Kojo continues to stonewall, but his business dealings remain under intense scrutiny and the report is not likely to make for pleasant family reading, says the source.

This is a story that clearly isn’t going away. Just last week, David Bay Chalmers Jr., an American oil trader, and Tongsun Park, a South Korean lobbyist, were indicted by federal authorities for kickbacks related to the oil-for-food program; conflict-of-interest questions have been raised about Maurice Strong, a Canadian businessman and U.N. special envoy linked to Park; and Annan’s predecessor, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, has been linked to Park as well (no charges have been filed against anyone but Chalmers and Park).

Annan is working hard, meanwhile, to salvage his reputation. In late March, he unveiled his ambitious, long-in-the-making U.N. reform plan. His goals are to replace the discredited Human Rights Commission, expand the size of the Security Council to fit the modern era, and officially define terrorism in harsher terms.

Annan has also been aggressively globetrotting lately—Geneva, Jakarta, New Delhi—simultaneously lobbying countries to back his reform plan and arm-twisting for international action to halt the genocide in Sudan. The efforts to do good seem to have bolstered his spirits. Annan has started to step out again. He and Nane attended a dinner at the home of Columbia president Lee Bollinger, and he received a warm welcome last week at the VIP screening of The Interpreter, the Nicole Kidman–Sean Penn U.N. thriller.

Candidates are actively campaigning to replace Annan when his term ends in 2006, but there are no signs of any effort to force a coup before then. At the moment, more attention is being paid to the embattled Bolton, whose confirmation is now in jeopardy because of allegations that he browbeat staffers at the State Department.

As I was typing away on this story, several days after the Volcker report came out, the phone rang. There was a familiar voice on the other end. “It’s been a crazy week,” said Annan. He told me he had been thinking about our previous interview and wanted to talk more. We wound up speaking for 40 minutes on a Saturday morning, as rain slashed down outside.

The secretary-general began by attempting to spin his situation, emphasizing all the calls of support coming in. Earlier in the week, he had spoken, with evident pain, about the friends who had seemingly vanished: “Some feel embarrassed to call,” he allowed. “They don’t know what to say.” Now he wanted to tell me that, among others, a sympathetic Bill Clinton had phoned. “He understands. He had gone through similar situations where he’s been under a microscope, attacked,” said Annan. Then he added, with a sense of surprise, that the former president had confided in him. “He was sort of reminiscing with me, sharing his own experiences with his brother, his brother-in-law, things like that.” Did Clinton offer advice? “That you have to remain focused and carry on.”

Annan admitted that he can understand why people might read the Volcker report and wonder, “ ‘Is something rotten in the state of Denmark?’ Which is a reasonable question to raise.” But he insisted yet again that he has done nothing wrong. “I walked into this with a clear conscience.”

Kojo had called him several times in the previous few days. After reading the Volcker report, with its appalling details of how Kojo hustled to make money, Annan said he was so angry that he kept the conversations brief. What did Kojo tell him? “He was sorry he hadn’t leveled with me. He’s obviously ashamed.” Annan clearly doesn’t want the 31-year-old to feel abandoned, yet he’s obviously devastated by his son’s betrayals.

Despite his “Hell, no” earlier in the week, I asked whether resigning has seemed increasingly appealing. “You think it through. What would be the best for me to do, to stay, to leave? Resignation would be easy, but to stay on and confront, pick up the lessons, push for the reforms you believe in, and work with the member states to get it done is much, much harder. Having balanced the arguments, I have an obligation to finish what I started.”

I mention that several ambassadors had speculated that Annan would remain only through the Security Council meetings in September, in hopes of salvaging his legacy through a victory with the reform package, but would then leave—a year early.

“That’s a question for the future,” he said. “In life, you cannot rule out, you cannot say never or forever.”