One evening, before her arrest, Jackie calls. I recognize the strong accent, the deep, gruff voice on the brink of emotion. Her name is really Ayferafat Yalincak. But everyone calls her Jackie. We speak often these days. Jackie seems to have designated me a person she can count on. This evening, she tells me she’s just back from a visit to her son, Hakan, who is confined to the New Haven County Correctional Center.

“How is Hakan?” I ask, as I always do.

“Not doing good,” Jackie says gloomily, as she always does.

No doubt. Twenty-one-year-old Hakan is the New York University senior the government calls an “economic danger to the community.” The threat, in the government’s view, is that Hakan is intent on getting his hands on other people’s money. To start, there’s the counterfeit $25 million check he tried to cash, which led the U.S. Attorney in Connecticut to charge him with bank fraud. (With transfers, the government says he tried to get $43 million.) The government has also targeted the hedge fund he began as a college junior. There was real money in the hedge fund. Hakan, with Jackie’s help, raised $7.4 million from sophisticated investors. Plus, there’s his suspicious $1.25 million gift to NYU—where did that money come from?

Jackie no doubt guessed that she, too, was under investigation. She, though, has more pressing concerns. Her boy, slight, to her mind, frail, and housed with violent criminals, is suffering. “He is spitting up blood,” she tells me. Jackie, I know by now, has a descriptive gift. At various points, she’ll report that her son hasn’t eaten for ten days, has a raging fever, and has blood coming out of his eyes.Jackie and Hakan are very close, seemingly two halves. “I don’t care for money,” Jackie once told me. “Hakan is … special. I love him to death.”

Jackie had always shown Hakan off. To enroll him in school early, she marched him before teachers. “Do some math,” she instructed him. She started Hakan on piano and violin and taught him English by making him say the English name for foods he wanted. “My father is the easy parent,” Hakan says.

Even as an NYU student, Hakan lived at home. If he stayed up late, Jackie checked on him and then tucked him in. It’s a real love affair, and Hakan, I know, feels the same. After bail was denied, he burst into tears. “Crying for his mother,” as a visiting lawyer put it.

Now Jackie’s calling to tell me that Hakan has no visitors other than his parents—even his sister hasn’t yet been cleared. Along with everything else, she’s worried that Hakan is lonely.

“If you visit, that would make him very happy,” Jackie tells me.

I’d like to, I say, but authorities have turned down my request.

“You’re on his visiting list,” Jackie says in a whisper. I’m surprised, but she insists, “I saw your name.” Then she asks, “Do you know what he looks like?” As if he hadn’t been dubbed the “Sultan of Swindles” by the Post, with his photo all over the place, but is merely her forlorn and defenseless son, in need of a friend.

“Yes,” I assure her. I plan a visit, though I can’t help but wonder if Jackie might be baiting a hook … for me. The U.S. Attorney would have me believe that an overture like this is a lure, a bid to involve me in the ornate, gothic, criminal drama of their lives.

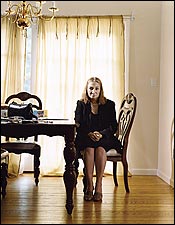

I first met Jackie at the lovely house her family rents in Pound Ridge, New York, a community of winding roads, hiking trails, and stone walls a few miles from Greenwich, Connecticut, where Hakan’s hedge fund had shared an office with his mother’s mortgage business. The house, at first glance, seemed to have several entry doors. While I waited at one, Omer, Hakan’s father, appeared at another, a small white dog in each arm. Quickly, he led the way to the living room, to Jackie and to Hakan’s younger sister, Hale, a senior in high school.

“We were waiting two graduations,” Jackie says dolefully.

Jackie installs herself on the couch, looking regal; mostly it’s the hair. She’s a 50-year-old Turkish woman with wide-set eyes, a pyramid-shaped eyebrow, and electric blonde hair.

“Where did you get the name Jackie?” I ask, just to start things off.

“People call me Jackie. I don’t use Jackie name at all,” she says. Apparently, there’s to be no small talk. “Whatever document you are asking, I am ready to show,” she announces. She places a Brioni shopping bag full of documents beside her. The government has seized papers and computers. “I received those today,” she says and tucks her hand into the bag, a pantomime, I think, of candor. “If there’s any money stealing or anybody lost the money, I have a proof, all, everything.”

Jackie is supposed to come from money—“old money,” “billions,” people in Greenwich say—and the house is stately, a home for a very comfortable family. From the living room, I can see a run of woods beyond the backyard.

“How many bedrooms do you have?” I ask.

Jackie pauses as if to reflect. “Lot of bedrooms,” she says.

And yet the furnishings seem almost makeshift. Plastic covers the white seat cushions, the lampshade. The arm of my chair wobbles. The coffee table and couch are a faux-antique-y set. Sheets drape some windows, to keep out a nosy press. Walls are nearly bare.

“You drink orange juice or Diet Coke?” asks Omer, who appears with both. He returns with Marlboros, for Jackie.

The family arrived from Turkey, where they are still citizens, in the nineties; “1998,” Jackie says, though later in the conversation it seems to have been 1996 or even, according to Hakan, 1992.

In any case, they came “for the good education.” And, Jackie points out, not just for her own children. The Yalincak Family Foundation has pledged a total of $21 million to NYU, and also awards scholarships. “Ten students we have on scholarship,” says Jackie proudly.

“Do you know the name of anybody you gave a scholarship to?” I ask. I could speak to them, I suggest.

“McCormack, last name,” Jackie says, “and Rachel.”

“McCormack?”

“Hale! Hale!” shouts Jackie.

“Coming!” calls Hale, who’d slipped away.

“My daughter keeping the name,” she explains. Hale rushes in. “What is the last name that McCormack person?”

“I’ve just called him McCormack.”

“Do you have … phone number?” asks Jackie.

She has McCormack’s number, but only nine of ten digits. A little later, the phone rings. Apparently, it is McCormack. Jackie passes me the phone. He doesn’t want his full name mentioned, but he says that, yes, he receives a scholarship from the Yalincaks.

Omer materializes again. He has graying hair, a mustache, a soft yellow sweater, and house slippers. He carries in his hand a diploma—his diploma—from a leading Turkish medical school. He also trained in Japan, where the family lived for a time, and bolts up the stairs for that certificate.

You’re a surgeon? I ask when he returns.

“Six-hour surgeries,” he says dramatically.

It led me to wonder if he had helped her when she impersonated a doctor in Indiana, as reports indicate. She supposedly posed as Dr. Irene Kelly, for which she is said to have served time in prison.

“There is no such a thing as this,” says Jackie, as if this is all too much. “I mean, there isn’t anything like that at all.”

Did you guys ever live in Indiana?

“Never,” she says, as if she might be ready for a scrap. “Never lived in Indiana. At all.”

What she says makes a certain sense. Who, really, could take this Turkish woman with the heavy accent and the Turkish husband for Dr. Irene Kelly, supposedly a Canadian-trained internist?Having asked about one charge, I jump to another. How about that counterfeit $25 million check?

“Somebody gave it to … my daughter,” explains Jackie. Hale, with her long dark hair and snug, stylish jeans and her unaccented English, seems like a normal American teenager. “Yeah, I went to the door,” she says, on cue.

“Did the check have a name on it?” I ask, a journalistic reflex.

“I didn’t read a name,” says Hale. “I … gave it to my brother.”

Hakan was running a hedge fund, right?

“He was one of the best,” Jackie says, though she seems to have decided we’ve talked enough about such matters.

“Why don’t you bring Hakan information?” she says to Omer.

The Hakan information mostly covers his high-school days. “Hakan before collect the money for earthquake people,” Jackie explains. The husband, moving noiselessly in his soft slippers, carries into the room a giant poster of the check Hakan gave to the Red Cross to aid victims of a Turkish earthquake.

I read the check aloud: “January 13, 2000, for five thousand … ”

“ … three hundred and twenty-five dollars,” finishes Jackie proudly. The husband places the giant check next to his wife on the couch, casting her, it seems, as a game-show contestant.

Next, Hale takes me on a tour of Hakan’s rooms, starting with the study where he is said to have traded derivatives. Next door is Hakan’s bedroom, with a twin bed, a desk, nothing on the walls.

Back in the living room, Omer rushes in clutching a thick sheaf of paper. They are medication slips. There must be twenty of them. He waves them at me, like a fan, and points to Jackie.

“She’s a diabetic and heart problems—all that medicine for her.”

“Tizanidine, Lipitor … ” I read.

“She is very sick,” Omer says.

“Isorbide, NitroQuick … ”

“Some vessel is not working. Maybe she needs a surgery. Bypass surgery. And then diabetic. Terrible condition. Very serious.”

All this is made worse by Hakan’s bad luck.

“She lives only for her son,” says the husband, pointing to her.

Jackie, who has been nodding silently, lights a Marlboro.

“You don’t mind?” she asks. I don’t, though I think of a letter Hakan sent me. It closes with a P.S.: “Mom, don’t smoke.”

On the couch, a slightly darker gold than Jackie’s dazzling hair, she suddenly breaks into sobs. “We are having such a hard time right now I prefer to die. I do. I mean there is nothing left to live.”

At the New Haven County Correctional Center, I wait in a windowless room with a half-dozen black women.

“Legal visit?” the guard asks.

“No,” I say. “A friend.”

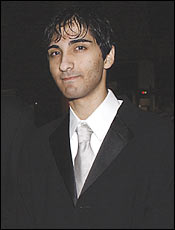

My name is on the list, as Jackie said. I march into a long, narrow room. Hakan is seated on the other side of a thick plastic window. We pick up phones. He is shaggy-headed and unshaven (for which he apologizes). He looks scarecrow skinny in those pajama-like things prisoners wear. He has light-brown eyes and dark-brown hair, a real mop of it, that is going red from the prison shampoo.

“Write quickly,” Hakan says. “We don’t have much time.” First thing, he wants me to know his correct age. “I’m 19, not 21,” he says, which he apparently learned only lately. And he has a twin brother. Or had. He died a decade ago. Leukemia, it seems. He is buried in Belgium or Turkey—I will hear both. This family, clearly, has a sideline in calamity. Hakan, too, is lately a cancer victim. “Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” he says and extends an arm for me to examine through the plastic divide. I nod gravely. Hakan says his cancer struck last year. Thankfully, it’s now in remission. Again I find myself nodding, though as I recall, his mother put the cancer years earlier.

I ask him about the $25 million check.

“That was from a life-insurance policy on my aunt,” who, naturally, died recently, Hakan explains breezily. With Hakan, there is intensity and breeziness, sometimes both at once.

Hakan’s defense against the charge of bank fraud is simple—maybe it was a counterfeit check. In that case, someone fooled him. Is it so far-fetched?

Hakan is personable, winning, in a precocious, hand-in-the-air way: He tosses out beguiling non sequiturs (he can’t seem to help himself), usually to prove he’s a prodigy. He speaks five languages, plus a little Hebrew; he reads the Torah and the Koran.

At the same time, the boy wonder seems almost theatrically inept in basic aspects of daily living. “I’m just a kid,” Hakan tells me. He doesn’t drive, so he sometimes took a car service to NYU. And he lugged around documents in a plastic bag, one time fishing out a check to pay his civil attorney, Robert Chan. “The stuff he wears most of the time would not be taken by Goodwill,” says Chan. More than once, Hakan showed up for a meeting claiming to have lost his wallet, and had to borrow money. Sometimes he didn’t show up at all, later mentioning, in that family shorthand, a broken jaw or a car accident. Once, he started a business e-mail, “My father had a heart attack today,” then turned to the day’s agenda.

The court files finally arrive: Jackie had impersonated an internist in Indiana. “That’s not me,” she insists. “Nothing to do with me at all.”

Hakan can seem to be driven not by a calculating criminal mind but by an exhausting and mostly self-destructive desire to please. He was, many say, a lonely kid. Still, on some Friday nights he plunked down his platinum card and bought rounds. He also sprang for a limo. “So no one would drink and drive,” he says.

Clearly, as a college kid, Hakan had unusual access to money, handy if you’re looking to impress. Once he bought some earrings for a pretty girl—“model pretty,” Hakan says, and looks almost sheepish. She was a Greenwich teenager named Amanda who worked briefly for his mother. One day, she said something flirty to Hakan like “You never buy me anything.” Hakan tells me, “It had been a very good day trading, so I bought her $3,800 earrings at Tiffany’s,” which he really did. (She confirms she got earrings.) Then he quickly adds, “And I bought something for my mother and sister, too, so they wouldn’t be jealous.”

Maybe it was a similar urge to please that led Hakan, out of the blue, to e-mail a dean at NYU about a gift. The dean invited an NYU development exec to a meeting. “They were shocked at the amount,” Hakan tells me giddily. Hakan, who high-school classmates thought lived in an apartment over a hair salon, said he had in mind a donation of $21 million of family money.

Even if a person prefers the view of Hakan as a goofy, bungling adolescent, “a kid with crazy hair in the air,” as he describes himself, there’s clearly another side to him. That is the financial sophisticate.

At the prison, there’s a crying little girl seated next to me; her cries fill the air like a siren. And Hakan, bursting to fill me in on the details, must nearly shout. “I started reorganizing my family finances when I was 12,” he tells me. “Initially, it was one hell of a depressing task,” he says. “I used to wonder why my life was so awkward.” Later, he came around, he says in a letter. (I’ll receive five—each with clumsy misspellings. “Priveledged” is one.) “It was my first real taste of freedom, and I liked it,” he wrote.

Hakan tells me about a family holding company he formed and the dozen related companies under it, offshore and onshore. All kinds of trusts, revocable and irrevocable, and in Turkey too. What really gets him excited, though, is talk of trading. “I would have loved to have been on a trading floor,” he shouts into the prison phone. Hakan’s trading skill is apparently the type that springs into being fully formed. He’d never worked as a trader, but credits his skill to books—his all-time favorite is When Genius Failed, the story of Long-Term Capital Management, the Greenwich-based hedge fund of Nobel laureates, whose collapse threatened the U.S. economy. Hakan, a student of that hedge fund, paid for research into its trades. That Hakan dreamed of being a hedge-fund guy I don’t doubt. He talks like a fan, relishing the trading tidbits as well as the minor details of real hedge-fund guys’ lives, the fancy car one drives or the stupendous sum another makes.

Hakan says he started trading at night. He traded Japanese bond futures, Eurex bond futures. “Basically,” he says, “anything that traded while school was out.” Sometimes he fell asleep on the floor while trading late. The night before his arrest, he tells me, his parents found him there and carried him into his twin bed.

On the subject of trading, Hakan can talk up a storm. “My trading lingo,” Hakan says and smiles, an alluring half-smile. Everyone confirms this. “He could rattle off what funds are doing in Italy, Japan, China, Hong Kong, you name it,” says Tom Andersen, who has his own accounting firm in Greenwich and met with Hakan several times. “He came across like some whiz kid.” One hedge-fund trader who met Hakan echoed the thought. “He’s like Einstein. He was talking a million miles an hour. He came off as brilliant,” says this trader, who also had an urge to tuck in Hakan’s collar, which flew in the air.

In 2003, when Hakan was 19 or, by the new math, 17, he began thinking seriously about Daedalus Capital Relative Value Fund, his second fund. Already, he says, he’d been trading family money through a fund he called Yasam Trading Group. He says it was very successful, although an audit turned out to be a fake, a misstep that Hakan told his lawyer was someone else’s fault.

Hakan tells me that when he hatched the hedge-fund idea, he approached Jackie, who hesitated. A heated discussion followed.

“Can you carry everything with school?” she asked.

Jackie was the mother who always wanted her son to reach for the stars. His father, more cautious, said, “Don’t overreach.”

Jackie asked Hakan, “How will you get investors?”

Hakan prevailed. “She had no choice,” he tells me with a beaming smile. “I’m a good salesman. I’m all about the numbers.”

Hakan is elbow-to-elbow with other prisoners—gang members, he tells me—as he launches into the numbers. It’s the Einstein routine. He mentions non-farm payrolls, swaps, and convergence issues. There’s one trade he seems really proud of. He peers through the thick plastic to make sure I write it correctly.

In the fall of 2002, he tells me, he put on a trade. “Turkish dollar bond credit default swap versus asset swap basis trade,” he dictates. He points to my paper with his eyes. “I made 300 basis points on $20 million. I made $2.7 million on that trade.”

The slurry of details, their exoticism: It’s like a burlesque of brilliance, and the fact that, as even I know, 300 basis points on $20 million is $600,000 hardly seems to matter. (He’ll correct it later.) Hakan’s trading lingo is mesmerizing.

The crying girl next door has finally calmed. But the hour is up. I linger as visitors file out. Hakan has a last question. “How will I get a job when this is over?” he asks. Lately, he’s been reduced to trading with his cell mate: In return for math help, he gets oranges.

For any new hedge fund, the challenge isn’t trading—anyone can trade, for better or worse. The trick, as Jackie had sensed, is raising capital. How was this kid with grooming challenges and blank spaces on his résumé, not to mention that indelicate fake audit, going to entice wealthy people to part with their money?

Jackie was willing to help. Through her mortgage business, she knew two real-estate developers. Brothers Leonard and Joseph Cannavo had invested in Hakan’s Yasam fund and were getting returns. “Actual money,” says Tom Andersen, their accountant. The Cannavos increased their investment in Daedalus to more than $1 million. Yet, as pitch person, Jackie had certain limitations: her Marlboro habit, her scrappy English, her implausible hair.

“I like her hair,” protested Hakan.

Still, with Jackie, if a semi-diligent person punched her name into Connecticut court records, a dismaying trail of creditors popped up. As far as Jackie went, there was, as one wealthy investor’s rep put it, that “Addams Family feel.”

And then, in 2003, Hakan met Matthew J. Thomas, a banker who could have been sent by a casting agent. Thomas, 38 at the time, six-foot-something, had light-brown hair, Waspy good looks, and credentials—there’d been stops at Banco Santander de Negocios, Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse First Boston. Plus (this would prove important), Thomas came with a flaw: credit-card problems.

The partnership seems to have gotten started over a takeout vindaloo dinner at Hakan’s parents’ house. Thomas worked for the venture-capital firm Spencer Trask and was hoping to pitch investment ideas. Quickly, though, the dinner morphed. “How to finance our own [venture],” as Thomas puts it in a thank-you note. Thomas’s idea: credit cards.

Thomas may look like a reassuring Protestant banker. But within months he was getting disturbing messages from U.S. Postal inspectors, federal agents who investigate credit-card fraud. Thomas turned to Hakan, wondering about a loan. By the end of 2004, he had signed two promissory notes to the Yalincaks—they totaled $925,000. What they covered, and how much Thomas got, is in dispute. But, this much is clear: Hakan now had a useful ally, a boon to the business.

Thomas could socialize with clients in a way Hakan couldn’t, even if some of his frat-boy behavior embarrassed the whiz kid. After a dinner at Restaurant Jean-Louis in Greenwich, Hakan says, he sent Thomas back to Manhattan in a limo with a prospect. “He farted,” Hakan bursts out, in giddy horror. “What a way to impress a client!”

And Thomas had valuable contacts. In particular, he knew Joseph Healey, who co-manages Healthco, a hedge fund that partnered with SAC Capital Advisors, the fund for which Hakan sometimes dreamed of working. Thomas seemed to know Healey pretty well. For one thing, Healey had dated Thomas’s sister. A few weeks after signing a promissory note, Thomas took Hakan to see Healey.

The pitch is a challenging, many-levered thing, especially for a teenager. Some investors like a dog-and-pony show. Daedalus shared office space with Jackie’s mortgage business. One day, Japanese investors poked their heads in. It must have seemed impressive: young people working away at computers. Actually, it was Amanda, the Greenwich girl with the Tiffany earrings, and a bunch of friends instant-messaging one another.

Most investors focus on the paperwork and the people, both of which Hakan and Thomas seemed to have in order. Daedalus had apparently lined up the right banks—Morgan Stanley, UBS—and a respected attorney, who filed the right forms. Hakan pulled out his trading lingo. And Thomas had that résumé. “Thomas is the one who had the ear of our clients, not Hakan,” says a lawyer for investors. Plus, Hakan and Thomas distributed reports that the fund was performing spectacularly. Up 48 percent, said an October 2004 statement.

It didn’t hurt that Hakan’s pledge to NYU was just then getting publicity, suggesting that the nerdy kid was from a family to be reckoned with. Recently, NYU had used a $1.25 million down payment to convert the old Bottom Line music hall into the Yalincak Family Foundation Lecture Hall.

Hakan, also, seemed to spend like a hedge-fund guy, another confidence-builder no doubt. Using Daedalus’ Morgan Stanley account, he paid for dinners at expensive Jean-Louis, jewelry at Tiffany’s. He bought a $68,000 Porsche for an employee. According to bank records obtained by New York, Hakan also used the account for walking-around money, haircuts, groceries, and even $1.40 at McDonald’s near NYU.

In any story, the lies matter less than the judiciously placed truths. If the Yalincaks donated a building to NYU or bought an employee a Porsche, why couldn’t they run a big-time hedge fund or even, as they told one investor, open a bank on Lexington Avenue? Healey wrote a check for $250,000 and soon brought in his partner, Arthur Cohen, who kicked in $1.25 million.

Thomas and Hakan were off to another acquaintance of Thomas’s, a young, wealthy Kuwaiti named Waddah al-Mousa, who—this seemed to tickle Hakan—wore sandals a lot. Al-Mousa’s family had helped raise $30 million for Pulse~LINK, a California tech company that al-Mousa chaired. He invested $250,000 in Daedalus.

To Hakan, it must have all seemed very clubby. The dinners, the casual clothes, the farting, and in this atmosphere, it probably wasn’t difficult to press assurances on people. The important thing, Thomas and Hakan let investors know, was that if they increased their investment and pushed the fund’s assets to $5 million or $10 million or name the number, then Jackie would kick in $20 million of the family fortune. Perhaps, as one investor’s adviser concluded, “if this kid falls on his face, there’s money behind him to bail him out.” It worked like a charm.

After Thomas, with the entire Yalincak clan in tow, unexpectedly showed up on al-Mousa’s California doorstep, the Kuwaiti family’s investment jumped to $750,000. Healey’s and Cohen’s investments soon totaled $2.8 million. With Frank Meyer and Robert Doede, two more extremely sophisticated investors (Meyer had been chairman of Glenwood Capital Investments, a $5 billion fund that invests in hedge funds; Doede, head of Centurion Capital), the hook was the same. Hakan showed the prospectus—some versions listed al-Mousa as a member of the executive committee, a shock to him. Hakan gave Meyer the line about Jackie’s $20 million. Meyer and Doede hurriedly wired in $2.75 million. Unfortunately, on Hakan’s instructions, he sent it to a Yalincak family-holding-company account, rather than to a Daedalus account.

By May 6, 2005, the day Hakan was arrested, Daedalus had collected $7.4 million in outside investments, a lot of money to spend, if that’s what one has in mind.

A $20 million check from the Yalincaks was, in fact, deposited in Daedalus’s Morgan Stanley account October 21, 2004. It bounced eleven days later, but by that time it had served its purpose—al-Mousa was among those who saw a statement showing that the fund totaled $20.8 million.

In the days leading up to her arrest, I speak to Jackie often. She is gloomy. No one does gloomy like Jackie. There is the door-creak voice, the cascading health symptoms.

“How are you?” I ask.

“Not good,” she says, adding, in her special way, “Diabetes, heart.” Though her main worry continues to be Hakan. “Another inmate stab Hakan with a needle,” she tells me.

“Is there anything to do?” I ask.

She’s thinking about bail, which the judge said was possible if a suitable sponsor came forward.

“Do you know anyone?” Jackie wonders, which suggests, among other things, how isolated this family is.

I tell her I’ll look.

“I will pay,” she says.

As I ponder all this, Irene Kelly’s file arrives from an Indiana Superior Court. Denials notwithstanding, Irene Kelly is Ayferafat Yalincak and, now, I guess Jackie. Irene/Ayfer/Jackie—she’d been dark-haired in Indiana—impersonated an internist for six months in Indiana. Apparently her heavy accent and her baffling writing (her letters to the judge are in elementary English) didn’t immediately bother anyone. She’d forged documents and nicked the identity of a Canadian M.D., for which she spent almost two years in prison.

Jackie’s lie is so bald-faced, so inept, I wonder, how could she have insisted to me? I call her, angry at first, but soon resigned, the way so many others must have felt. Jackie is unyielding and, of course, believable. “That’s not me,” she says, dismay in her voice. “Nothing to do with me at all.”

I tell her that I also have probation papers that discharge her to 15 Charter Ridge Drive, Sandy Hook, Connecticut, the same address to which Thomas goes for vindaloo, the same address to which an NYU senior VP for development sends a thank-you note for the pledge to create the Yalincak Professorship of Ottoman Studies. (If any doubt lingered, Ayfer/Irene also has Jackie’s trademark, listing for the judge her recent afflictions: herniated disk, TB, ulcer, gallstones, cervical cancer.)

“Something is wrong,” Jackie tells me as if, momentarily, understanding my point of view. “I’m waiting for Hakan. After all this I will go back and talk to those people.” There’s more in the file. As part of her sentence, Jackie repaid a minister at Post Road Christian Church who’d lent the Yalincaks $4,200 from his retirement fund. “They didn’t have food,” says Minister Donald Johnson. A few days later, I come across a letter from a pastor who’d served in Japan when the Yalincaks lived there. He’s a Seventh-Day Adventist named Michael Walter, and he lent the Yalincaks $4,000 of his own money; he never got repaid.

With Jackie, as with Hakan, facts turn out to be mutable things. I do some checking. Finding inconsistencies is like a drinking game, fun for a while. For instance, UBS is not, as Hakan reported, Daedalus’s offshore administrator. (The UBS CEO in the Cayman Islands doesn’t believe the fund exists.) Anchin, Block & Anchin has done no auditing work, though it is the auditor in forms. The Yalincak Family Foundation is not a Delaware corporation, though that’s what Hakan told me. And, when Pastor Walter met the Yalincaks in Japan in 1991, he saw just two children. I don’t believe Hakan had a twin brother, buried in Belgium or in Turkey.

The untruths, along with Irene Kelly’s thick file, leave little doubt: Jackie was a con artist—and not a very sophisticated one. Hakan, I can’t help but think, offers another possibility. With his overachieving ways, his facility for math, his hereditary intrepidness with the facts, he is a generational improvement. After all, posing as a doctor isn’t really much of a fleecing. Jackie wore a bright white coat. Still, she punched a clock. The next iteration, though, offers enhancements. It’s the big con, the one in which the mark not only invests but goes home for more, as did Cannavo and al-Mousa, and Healey and Cohen.

“We are not hedge-fund people,” Jackie once told me. And yet, for a con artist little is better-suited than a hedge fund. There are no credentials to forge. Indeed, anyone can run money; as long as a manager reports good results, investors stay happy. And as long as you keep raising money, you’ve got a good shot at staying in business.

Whether or not Hakan made many trades, little of what he did looks like a hedge fund. I asked one of Hakan’s lawyer’s if he had records of trades. “No,” says Chan, “and not for lack of trying.”

As for the $1.25 million that Hakan gave a beaming NYU as down payment on his $21 million pledge: Those funds came again from Daedalus’ Morgan Stanley account, mainly, say Cohen’s lawyers, from investments by Cohen and Healey.

Together, Jackie and Hakan, along with their indispensable props—a Waspy, credit-poor Matthew Thomas; a white-shoe attorney; and a grateful NYU—managed to convince people who ought to know better that an undergrad history major was running a hedge fund after classes.

What Jackie and Hakan have left is each other—and me, possibly their last friend, or, I sometimes imagine, their final mark. Jackie turns to me now, as if we have a special bond. Perhaps we do. It’s funny, but even with all I know about her, I can’t help but like Jackie, her hectoring English, her maternal insistence, pinching in at every edge. Even her hallucinatory claims—family fortunes and people dying (Hakan told me another brother keeled over just last month) and multi-million-dollar checks arriving at the door—these stories, I find, have the charm of entertainment. Who else works so hard?

Lately, I recall Jackie with her shopping bag of documents on that couch, asking me, “Who got hurt? I can’t see.”

The U.S. Attorney will take another view. The morning after Jackie promised me that she and Hakan would get to the bottom of the Irene Kelly mix-up, she is arrested. Hakan too is charged again. They’d always been in this, in everything, together. Last week, they were in handcuffs in the same court. The government says they used fake documents to lure investors into a hedge fund that appeared mostly phony.

I think of one of my last conversations with Jackie.

“How are you?” I’d asked her by phone.

“Not good,” came that shoe-scrape of a voice. “Last night coma.” Jackie’s escalating symptomatology was, I knew by then, a kind of lobbying. This woman suffers, help her. Who could blame her? She still searched for someone to sponsor Hakan for bail. We put our heads together. Who?” I wondered, playing my part.

“Clergy, maybe,” said Jackie. Of course.

Jackie was calling from the road. She was on her way to see Hakan; she went every day. There was one more thing. “Will you visit him?” she wanted to know. He was still lonely. “He likes you.” Whatever else she is, Jackie is an unshakably attached mother. That, at least, I believe.

“I will,” I said.