On a warm Thursday night in August, two days before she died, Maria Pesantez, a tan, blonde 18-year-old NYU scholarship student with an appetite for punk rock, was running down her cell-phone battery in her bedroom in Jackson Heights, Queens, laughing and flirting with her boyfriend, Nick Genovese, a bass player in a blisteringly loud college band called Elysia Falls. It was a few weeks before what would have been the start of her sophomore year, and Maria couldn’t bear to be apart from Nick, who was spending the summer at home in Washington, D.C. The call went on for so long that Maria had to ask to borrow her sister’s cell phone to keep talking. All the while, she was multitasking on her laptop, scouring the Web for a stray ticket to the Warped Tour, the hardcore megashow with one of her favorite bands, Fall Out Boy, that was coming to Camden, New Jersey, that Friday and Randalls Island on Saturday. But it was no use. Although many of her friends had tickets, Maria was shut out.

From an early age, Maria had been the family achiever—the good daughter destined to fulfill her immigrant parents’ high expectations. Marcia and Juan Carlos Pesantez had moved to New York from Ecuador when Maria was 7, and almost immediately Maria stood out. With a mind for math, Maria earned straight A’s with little effort at Saint Vincent Ferrer High School, an all-girls Catholic school on Manhattan’s East Side that she’d attended on scholarship. If she cut loose at all, it was with punk—the Ramones, the Clash, almost anything loud. And with fashion: Maria had several ear-piercings and for a time dyed the tips of her hair red, hiding both alterations from her teachers with a wig. She was a little chubby, but dressing like a punk allowed her to conceal her body with oversize band T-shirts. Maria and a few close friends mostly hung out at each other’s houses; now and then they’d save up to go dancing or to a concert, but her mother could count on one hand the times Maria came home late with alcohol on her breath. In her senior year, everything Maria had worked for paid off. She was accepted at both Columbia and Harvard, but she turned down both to stay close to home and attend NYU, on an almost full scholarship.

In her freshman year, Maria had begun to change. Thanks to Herbalife, a gym regimen, and liposuction during winter break, she had lost 30 pounds. Lately, Maria had been taking pictures of her new, thinner self, and she’d laugh triumphantly when people told her she looked like Mariah Carey. She loved meeting boys, going out to shows, and staying up late; drinking was a big part of that, too. A year ago, she pierced the underside of her tongue without telling her parents. But she’d still pop by Jackson Heights for surprise visits, and bring friends back to crash on her parents’ couch and have pancakes the next morning.

During the summer, Maria and her family had spent six weeks in Ecuador, and Maria now seemed determined to get out and have fun. Warped was a perfect chance. That night, Maria’s parents were somewhat startled to hear her complain that if she’d stayed home from Ecuador, she’d surely have a ticket. She went to bed fuming. But early the next morning, the promise of a ticket appeared to materialize from her high-school friend Mellie.

Like Maria, Mellie Carballo was a talented and charismatic daughter of hard-working immigrants. Her parents looked on her not as a golden child but as a force of nature—independent, unpredictable, eager to bypass teendom for the larger adult world. Mellie’s grades at Saint Vincent’s were not as good as Maria’s. She was the class iconoclast—a precocious individualist who made up her own fashions and fit into no clique. Maria had played at being a punk, but Mellie was more like the real deal; she had dyed the tips of her hair a shocking blue and didn’t bother with a wig. She went out to shows on weeknights and hung out with the bands afterward until dawn. Mellie had left Saint Vincent’s a year early and finished elsewhere but had kept in touch with Maria after she enrolled at Hunter College. An exotic beauty with alabaster skin, ebony hair, and cheekbones that ached to be photographed, she was thinking of becoming a model; in December, she’d gotten a nose job.

And although it had been a few years since Mellie and Maria were close, they were friendly enough for Mellie to have called Maria at 7:45 on Friday morning, August 12, with the promise of a ticket.

At 8 A.M., Maria walked into her mother’s room. “Mami,” she said, “I’m going to New Jersey.”

“No,” said Marcia. She had chauffeured her daughter and her friends to the Warped Tour the previous year, but this year she had to work. (Marcia is a supervisor at a jewelry wholesaler in Long Island City; Juan Carlos is a parking-garage attendant in Manhattan.)

“Mami, don’t be mean!” Maria said. “Don’t do this to me!” Maria got onto her parents’ bed on her hands and knees and bounced up and down like a little girl.

“OK, mi hija,” Marcia said, astonished. “Who are you going with?”

“With Mellie.”

Marcia hadn’t remembered Mellie’s name; that, she would say later, is how unconnected that girl was to her daughter.

“How are you getting there?”

“On the bus,” Maria said.

“OK,” said Marcia, “but please don’t come home late.”

Maria ducked into her 15-year-old sister Karla’s room—“Karlita, I’ll take you to the beach another day!”—and kissed her sister Daniella, 7, on the cheek. As Maria was walking out the door, her mother looked at her one last time. She was wearing a striped shirt and tiny white miniskirt—so short that Marcia couldn’t help but blurt out, “Are you wearing underwear, Maria?” She remembers it now as a tender, just-us-girls moment, tempered with a giggle.

“My love, you look beautiful,” Marcia said and blew her a kiss.

Sometime after nine that morning, in the kitchen of a sun-drenched West Side apartment, Mellie Carballo was eating a bowl of cereal as her mother, Mariel, sipped her coffee. Mariel teaches at a local Montessori school; Miguel, Mellie’s father, is the superintendent of their building at 59th and Columbus. Mariel and Miguel had saved to send Mellie and her older sister, Celeste, to private school. Now, with both in college, the hard part of parenting seemed over. That their daughters still chose to live at home was a bonus.

That morning, Mellie didn’t mention the Warped Tour to her mother; instead she said she’d be spending the weekend at a friend’s place in the Hamptons. Mellie finished her breakfast, said good-bye, and darted out the door, her slender arms hauling a vintage, heart-shaped brown leather suitcase she’d picked out on eBay.

A moment later, she came back through the door.

“This bag is toooo heavy,” Mellie said.

“Why don’t you use my bag?” said Mariel. “It has wheels.”

Mellie repacked, then breezed out the door, light as a feather.

It was the mothers, Marcia and Mariel, who got the twin phone calls from the hospitals. Shortly after 6 P.M., they were later told, Maria Pesantez and Mellie Carballo were found unconscious in a drab two-room apartment on the ninth floor of a Lower East Side housing project. Mellie was pronounced dead on arrival at Cabrini Medical Center; her body was still warm when Mariel arrived. Maria held on a little longer at Bellevue before dying on Saturday, her mother Marcia’s birthday. Police said the girls had spent much of the afternoon with Roberto Martinez, a 41-year-old paroled drug dealer, and Alfredo Morales, a 33-year-old maintenance worker with a record of drug possession who grew up in the building and lived in the apartment. The toxicology reports on both girls showed the presence of cocaine and heroin in their systems.

Almost instantly, the girls’ lives were probed and gossiped about and even fetishized. Information surfaced that police had found needle marks on their hands. People noted that Maria’s Myspace.com home page contained a photo of her swilling a cocktail and a list of favorite movies including Trainspotting and Requiem for a Dream—the Citizen Kane and Grand Illusion of the drug-movie canon. Alluring photos of Mellie appeared on a downtown dance-party Website, and her memory was saluted by a number of risqué clubland blogs. Suddenly, Maria and Mellie were David Lynch characters—good girls with dark secrets.

I’m having lunch with Mariel and Miguel Carballo. It’s been a month since their daughter died, and they’ve just visited the housing project where she and Maria overdosed. They appeared as guest speakers at a press conference for a tough-on-drugs City Council candidate named Mike Beys. “I do not want Mellie’s death to be in vain,” Mariel told the handful of assembled journalists. “There were two men with long-standing criminal records who were with my daughter. I am here today to speak for justice.”

Despite the evidence to the contrary, Mariel doesn’t believe Mellie had a drug habit; if she did, Mariel says, Celeste, with whom she shared a room, would have known it. Mellie had been home a lot in July, at around the time police and friends say she met Roberto Martinez; Mariel noticed no changes in her behavior. Besides, when Mellie had had her nose job in December, the doctor would have noticed signs of regular cocaine use, had there been any. Mariel believes that Martinez and Morales are simply “predators” who took advantage of two young girls who, while not entirely innocent, were by no means hard-core drug users, either. “Mellie was 18—she could vote and do other things, but she still was a child,” Mariel says. “You know, the line is very thin when they move from 17 to 18. They’re still young. That’s why she was living at home, because I felt like she still needed to be surrounded by adults who can guide her.”

Both Mellie’s and Maria’s parents note that when police arrived at the apartment where the girls were found, no drug paraphernalia was on the scene—a fact both families find suspicious. It’s possible, they say, that Martinez and Morales, seeking to hide evidence, wasted valuable time that could have saved their daughters. “They didn’t give them the chance to help themselves,” Mariel says. “They’re dead, two girls, and they were together with these two men. Not kids. They were men. It was something they did to try to make them addicts, so they would be their customers.”

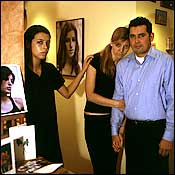

On another night, I’m sitting in the Pesantezes’ living room in Jackson Heights. Maria’s college I.D. photo is blown up to an eight-by-ten and rests on the mantle, not far from a rendering of The Last Supper. Marcia and Juan Carlos are on the couch, leafing through their daughter’s old report cards. Marcia, too, has a list of refutations for everything that’s been said about Maria. Would a junkie, she says, be able to spend six weeks in Ecuador with her family without showing a single sign of discomfort? Those drug movies, like Trainspotting? She brought them home to educate Karla and enlighten Marcia. That photo of her drinking? “That was taken in Ecuador, at my sister-in-law’s house,” Marcia says. “She was with her cousins and they made her drink, and she put that photo on the Web so that her boyfriend could see it.” You might think the two families would be bound together by mutual grief. But they have not spoken since just after the wakes. Marcia will not say anything negative about Mellie. “Let God be the judge,” she says. But Juan Carlos has something to say. “We’re not Jesus Christ who turns the other cheek,” he says. “No, we need to clear up what the truth is. From here forward, we are going to clean up my daughter’s name.” He believes the facts will eventually show that Mellie Carballo was working as a roper for Martinez, luring in new girls in exchange for drugs.

“I know that Maria would, if Mellie asked her to, to ‘please come with me quickly to drop off this bag at my friend’s house,’ she would go up,” he says. “I think that Mellie does the drugs first and she passes out. So these guys decide that they can’t have a live witness and so they make Maria do the same. Then they can wash their hands of it, put it all on them, saying that they brought the drugs, or they wanted to do the drugs, or they set it up. They killed Maria so she wouldn’t be able to talk! I say to you, Maria has to have had some kind of pressure, maybe a fist, or a gun, because we’re not sure that Maria would have gone into that apartment with those men voluntarily.”

The police insist there’s no evidence to support this, but it’s what Juan Carlos clings to now—the idea that his daughter was tricked. He thinks Mellie had been trying all that night to recruit other girls to come with her, before finally finding a mark in Maria. Marcia, meanwhile, keeps looking for any sign that Maria was innocent. She has begun to ask the medical examiner if someone could have slipped Maria a pill. It’s a quixotic theory, but Marcia keeps calling.

When they’re told what Juan Carlos is implying about Mellie, Mellie’s parents turn pale. For Mariel, any suggestion that her daughter is to blame is more than insulting. It misses the point. “I don’t care if Mellie had been doing drugs for two years!” she says. “I will never, ever blame either Maria or Mellie. If they had problems, they were our problems.”

Miguel is incredulous that one family might blame the other. “It never crossed my mind,” he says. “Whenever anybody talks about it, it’s Mellie and Maria, Maria and Mellie.”

Maria Pesantez and Mellie Carballo met during their freshman year at Saint Vincent’s. Maria had arrived with a ready-made clique: Two close friends, Bianca Berges and Michelle Adam, had come with her from junior high. Mellie was a new face—the kind of girl other girls took an interest in, with an appealing, almost preternatural confidence. She had a modified Valley Girl way of speaking, with lots of ironic attitude and one-word answers—Phoebe from Friends, by way of Daria. Bianca still does a decent imitation: “Ew. What. Is. That?” She laughs. “That’s a Mellie quote—‘Ew.’ People who weren’t nice to her, she’d say, ‘Ew.’ ” Then there were her nightlife connections. She was friends with hot bands like Sugarcult and would party with them backstage, yet she never acted as if it were a big deal. “She was like a scenester, always going to shows,” Bianca says. “She knew all those people. She was friends with them.”

When Mellie was out dancing on weeknights, it was with her parents’ blessing. “In Argentina, teenagers go home when the sun comes up,” Mariel says. “We have a nocturnal culture. I also go dancing.” Maria’s mother, meanwhile, would chain the door so she could smell Maria’s breath as she entered. “My love, I trust you with my eyes closed,” Marcia would tell Maria. “But I don’t trust others. If you go out with a girl who likes to stay out dancing and drinking, even if you don’t, you’re still exposing yourself to that. The devil is the devil.”

“Mami,” Maria would reply, “you don’t want to go out, so you have no idea what goes on out there. You think because you raised us well, we don’t hear bad words, we don’t see ugly things? We see it all. You can’t hide. You have to face things.”

By the end of her junior year, Mellie was outgrowing Saint Vincent’s, and she’d found a typically dramatic way to get out. With the U.S. in the midst of war in Iraq, she said she wanted to join the Marines—and even interviewed with a recruiter. “It’s cool,” she’d tell her friends. Miguel, an Argentine military veteran, was overjoyed. Mariel and Celeste were appalled. “I’d be like, ‘What are you doing?’ ” Celeste says. “And she’d say, ‘What are you doing? You paint. Are you going to paint for a living?’ ” Eventually, Mellie agreed to put off the Marines until after college. Before enrolling at Hunter, she spent what would have been her senior year completing her high-school credits over the Internet, assembling a modeling portfolio, and interning at MTV. She also stayed in touch with Maria, who last winter recommended and trained Mellie for a part-time job at the Manhattan promotions company where Maria had worked.

At NYU, Maria came off as the type of girl who didn’t like other girls, perhaps because she’d spent so much time at an all-girls school. There were plenty of boys, though—including Nick Genovese. Their friendship upgraded into romance toward the end of the spring semester. Nick says he’s too upset to comment for this story. But his bandmates in Elysia Falls all remember how she doted on them, bringing her family’s gray Sentra in from Queens to drag their equipment to gigs at CBGB, Continental, and Luna Lounge—often taking two trips. She seemed eager to impress them; she told them she could get their demo to the band H20 through a connection that, Bianca says, was probably Mellie. At Irving Plaza last spring, Maria’s friend Ian Folkert, the drummer in Elysia Falls, remembers her making a big show of hanging out backstage with members of Sugarcult.

Maria’s father believes Mellie was a roper, luring in girls in exchange for drugs. “We’re not Jesus Christ who turns the other cheek,” he says. “We are going to clean up my daughter’s name.”

In college, Maria wasn’t earning straight A’s like she used to. Another band member, Jonathan Carpenter, says he and she both flunked a computer class in the second term. Friends would see Maria drunk in the dorms—hardly a major transgression for a college freshman. The guys in the band say they never saw any drug use, but Maria’s high-school friend Michelle, who would visit the dorms with Bianca, says Maria experimented with cocaine. “I’ll be honest,” Michelle says. “She tried it. But she wasn’t an avid user.”

The Tuesday before Maria’s death, Michelle and Bianca say, Maria mentioned a friend who was doing heroin and said she would never try it. “I wouldn’t want to have something have that kind of control over me,” she told them. A month before she died, Maria went out of her way to tell her sister Karla that if she saw her coming even close to drugs, she would smack her. But Ed Gallego, an old childhood friend, believes Maria was ready to experiment. “All I can say is, I told Maria to stop,” he says. “She wouldn’t listen. She wasn’t the happiest person in the world. Her new life at NYU revolved around trying new things, to bring herself to a new high.”

Until recently, a photo of Mellie Carballo, smiling sanguinely, was on a Website promoting a Friday dance party called Trash, one of a string of parties with names like Misshapes, Bust, and Motherfucker that together compose a sort of intro course for hipster nightlife. Replenished by a steady stream of undergrads, the scene is almost sentimentally retro—New Order is as popular as disco-punk, and the regulars dress like it’s Limelight in 1987. These aren’t places where everyone’s waiting for Tara Reid to show up: They’re more intimate and cliquish, yet every bit as naughty. By the end of her freshman year this spring at Hunter, Mellie had become a regular. “She was a familiar face and around a lot,” says Sarah Lewitinn, who runs the Ultragrrrl clubland blog. “And so adorable, so cute, always well dressed. She’d wear a band T-shirt, tattered but fitted, a cute miniskirt. She seemed pretty popular.”

After Mellie’s death, one anonymous posting on a blog claimed that “me and Mellie on a number of occasions, in various locations, indulged on numerous ‘vices.’ ” Her sister never noticed anything. But Celeste does remember Mellie saying she had gotten involved with Trash’s well-known impresario, D.J. Jess.

“No one actually knows this, but Mellie and I were romantically together,” says Jess, a twentysomething club kid who, like Sting or Seal, goes by just one name. When they first slept together, Mellie gave Jess the impression it was her second time, but she wasn’t above bragging that the first was a “person of note” whose name he won’t divulge. He loved right away how self-assured Mellie was, how she liked to tease him. Jess makes a big show of being coy about his own age, but he didn’t find out that Mellie was 18 until after she died. “She wasn’t this drug fiend going to the clubs, looking for the drugs, going after her next fix,” he says. “Obviously, I was intimate with her, and it wasn’t part of our relationship.

“Mellie’s fearless,” he says, slipping into present tense. “She’s reserved, but not shy. And she’s not careless. She doesn’t waste her time, and you’re certainly not going to manipulate her.”

A pause.“Well, in retrospect … she wasn’t someone you could easily take advantage of.”

Jess was working several nights a week, leaving Mellie on her own for much of the summer. Mellie met Roberto Martinez in July at the Dark Room, a rock-and-roll bar on Ludlow Street that has held after-parties for Bowery Ballroom headliners like the Libertines and the Killers. Mellie may never have known this, but in 1998, Martinez was indicted as part of the Cut Throat Crew, an alleged heroin-dealing gang that relied on teenage couriers. She also probably hadn’t heard that Martinez had served six years for dealing and that a few years ago the crew was implicated in the murder of 18-year-old Evalene Santana, who was thrown off a rooftop on Avenue D, supposedly after she didn’t pay her drug tab.

Mellie told a friend that Martinez was a nice guy who wanted to be her boyfriend. She said it in such a way that it was clear he didn’t have a chance. But another friend of Mellie’s believes that Mellie got in over her head with Martinez—and adds that Mellie told her he was giving her coke on a regular basis. And it’s verified by many that on August 11, the Thursday night before Mellie died, Mellie was out on the town all night, not with Jess but with Roberto Martinez.

At the end of that evening, at about 5 A.M., Jess remembers Mellie visiting him at a club after he’d finished his show. They cuddled for a while—“It just feels so good being with you,” he remembers saying—and then he put her in a cab heading uptown.

Mellie went home and called Maria, had breakfast with her mom, packed her suitcase, and went back downtown, where Martinez later told police she reconnected with him after 10 A.M. The two of them met up with Maria soon after.

No one heard from any of them until about noon, when Maria’s cousin Diane spoke with Maria on her cell. They’d been talking about the Warped Tour earlier in the week. “I’m trying to get to New Jersey,” Maria told her.

At 12:30 P.M., Maria called Nick, too, only to cut off the conversation because, she said, she was going into an elevator. “I’ll call you right back,” she told him.

At 3 P.M., Marcia tried her daughter several times—the usual worrywart calls—and finally Maria picked up.

“Mami,” Maria said, “I didn’t hear it the first time. And when I picked up the second, you hung up too quickly.”

“How’s it going?” Marcia said. She heard loud music in the background.

“Everything’s fine,” her daughter said.

“When are you coming home?”

“Not too late, Mami. I’ll call you as soon as I’m getting on the train.” After that call, there was silence.

The police interrogated Martinez and Morales for several hours after the girls’ death, then released them. The two men admitted to taking drugs with the girls, investigators say, but insisted that they thought they were doing just cocaine, and that the girls participated consensually. Once out of police custody, however, Martinez and Morales changed their story and told reporters that they never took any drugs at all. Martinez claimed that they played Uno; Maria drank malt liquor with Morales while Mellie drank juice. When the girls got sleepy, Martinez said, the two men left the room—Morales says he went to get his car—and when they returned, Maria was turning purple. They tried to revive her in the bathtub, he said, but it was too late. Martinez later changed his story again, telling another reporter he wasn’t even there when the girls OD’d—that Morales had called him in a panic. Four days later, Martinez was sent to Rikers Island for violating his parole, and a day after that, police arrested Morales for drug dealing.

What police now believe happened is this: That Friday morning, Martinez had either sold or given the girls four small glassine bags of what all four of them had apparently thought was coke. Once they made it to the apartment, police say, the group snorted all four bags. (No track marks were found on the girls’ bodies; any needle marks on their hands, police believe, were from paramedics’ attempts to revive them.) Then they did three more bags Martinez had—and then another bag, from a separate supply, that Morales had with him. “We believe they did all eight,” a police source says.

Police also found Mellie’s suitcase on the scene. “There were two more bags of drugs in Mellie’s luggage,” a police source says. “One had residue and the other had enough that it was clearly coke. And we know she purchased drugs from Martinez in the past.” It’s not clear how or when the drugs made it into the suitcase.

Unless Martinez and Morales know something and decide to talk, we’ll likely never know why the girls went to the apartment. Were they on their way to Warped and decided on a pre-concert party that went too far? Or was Warped a cover story—were the girls seeking drugs all along? Did they do the drugs consensually? Did they know there was heroin in the coke?

The initial reports suggesting the possibility of a tainted batch of heroin—which police first thought may have also caused the deaths of six users around Avenue D that same week—have been all but disproved by toxicology tests. If there was such a batch, authorities say, it’s probably long gone; deadly product is bad for business. It’s still possible that a certain supply of heroin was too pure for some users to handle, but it’s just as likely that the girls died simply from mixing drugs.

Heroin deaths are no more common in New York today than they ever were. About 700 people in the city fatally overdose on heroin and other opiates every year. But certain cases still shock: Young, good-looking college girls aren’t supposed to be the victims in these stories; that’s not the accepted narrative. Yet it’s possible that Maria and Mellie’s exceptionalism is part of what killed them.

Even Juan Carlos, at the end of a late evening, suggests as much. “Maria’s greatest defect was her confidence,” he says. “She trusted herself too much. For me, that was her flaw. I always warned her, and she’d say, ‘Papi, don’t worry. I’m never going to do anything that’ll hurt me, or something that will hurt you.’

“But look what happened.”

See also

The Heroin Den Next Door