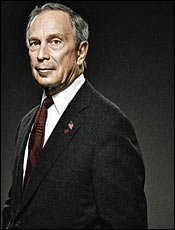

Michael R. Bloomberg, wearing his corporate-executive uniform of navy chalk-stripe suit, monogrammed shirt, and understated blue silk tie, strides briskly ahead of his aides through a security checkpoint into City Hall. He’s returning from a ribbon-cutting ceremony on Randalls Island, where the FireDepartment has built a new mock subway station to practice for underground fires and evacuations. I’m early for our interview, so I’ve been waiting on a battered wooden bench at the foot of the stairs to Bloomberg’s second-floor office. He shakes my hand, says he’ll be ready in a few minutes, and begins to skip up the stairs.

“Where’d you get the tan?” he asks suddenly.

“I don’t discuss what I do on my own time,” I tell the mayor. “My private life is private.”

He laughs loudly, getting the joke immediately. “Fair enough,” he says.

“Actually, I was on vacation with my family last week,” I tell him. “In the great state of Massachusetts. Cape Cod.”

Bloomberg freezes on the third step and turns to face me. “Ahhhh,” says the mayor wistfully (he grew up near Boston). “I’d like to be able to say that we went to the Cape as kids. But”—he scrunches his face, frowns dramatically, and lowers his voice to whisper—“we just didn’t have the money.” The volume comes back up to normal. “There was one family in our neighborhood, the Connollys, who were the only people we knew who had a vacation home. Lake Winnipesaukee, in New Hampshire. But we didn’t go there either. My father worked all the time.” He shakes his head and trots up the staircase to his office. The mayor’s tan, however, is far deeper than mine.

It has been a very long time since the 63-year-old Michael Bloomberg needed to whisper in embarrassment about his family finances. He could buy every beach from Bourne to Provincetown if he so desired. There’s no need, of course, because Bloomberg owns four palatial getaways, including a $10 million Victorian townhouse in London and a $1.5 million condo in Vail. He’s hardly used them since becoming mayor, but two days after we talked in City Hall’s second-floor “bull pen,” Bloomberg flew, in his own plane, to Bermuda and a mansion he built for $10.5 million. The trip didn’t appear on Bloomberg’s public schedule. As New Orleans deteriorated after Hurricane Katrina and the Bush administration’s bungling became a racial issue, Bloomberg jetted back to stage a Sunday-morning press conference trumpeting the dispatch of 450 New York cops and firefighters to New Orleans.

New York has always been a city of economic extremes. But four years after being elected, Bloomberg presides over a place where money has replaced race as the starkest dividing line. The forces leading to that polarization were in motion long before Bloomberg’s inauguration. Yet city voters, with their uncanny knack for the moment—choosing David Dinkins in a time of racial hostility and Rudy Giuliani when crime was rampant—are now poised to reinstall as mayor the perfect symbol of the city’s monetary divide, a man who rejected Gracie Mansion to stay in his $17 million Upper East Side townhouse.

“I went to Miami with the mayor for a meeting once,” says Police Commissioner Ray Kelly. “And when we were ready to fly back, there was some problem with the mayor’s plane. So we got on his other plane. That was pretty good.”

Bloomberg repeats endlessly that he’s “not a politician,” and that’s true in a couple of key respects: Until 2000, he’d never run for office or worked in government, and when he became mayor, his money freed him to make decisions unencumbered by traditional political debts. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t some quid pro quo. The mayor has replaced the clubhouse tactic of trading jobs and favors with a monetary system of reward and punishment that’s plenty “political.” The mayor’s wealth informs or shadows every decision he makes, from the business plan he uses to govern, to the push for the 2012 Olympics, to his expanding list of ostensibly private charitable donations. Democrats attack Bloomberg for giving millions to the Republican Party; Joe Bruno, the powerful GOP leader, is angry at Bloomberg for not giving state Republicans more money.

Taken out of political context, Bloomberg is among the more benevolent billionaires of his time. Instead of using his money to withdraw from the messiness of the everyday world, Bloomberg has thrust himself ever more into it. He’s given away hundreds of millions of dollars, no strings attached, to worthy causes, and scores of smaller gifts, anonymously, to friends and strangers in need. Even his multiple homes, though lavish, are essentially pragmatic: He bought a North Salem estate as a base for his daughter Georgina’s equestrian training. His company has a large London office, so Bloomberg has a large London home.

When the history of the Bloomberg administration is written, the question to be answered won’t be whether he was out of touch with the little guy. It’ll be whether Bloomberg was hampered by the grandiosity of his thinking. There is a numbing gigantism to the mayor’s vision of the city, to all those gargantuan development plans he’s pursuing across all five boroughs. And in order to further those plans, he is conducting a 100-ton steamroller of a reelection campaign. Big has been very, very good to Bloomberg. The question is whether it’s good for the city.

The mayor is in a good mood. One of the surest signs is that numbers and sales pitches, the language he’s most fluent in, start flying. “New York is different,” he says. “Remember all of the professors being quoted about the stadiums being too much? There may be too many stadiums in Akron. But there’s not too many stadiums here. There is a demand. People want to come here. Record tourism, 40 million—39.5 million last year. This year, we’re on course to shatter that record. There’s a fascinating statistic: One out of every four people in America has visited New York since 9/11. It is astounding. Now, I don’t know how you count it; it’s some people coming multiple times.” It’s a small example of an endearing habit of Bloomberg as mayor: He rolls out his spin, then undercuts it by pointing out the spin, like Penn & Teller’s explaining the magic trick they’ve just performed.

Then he’s describing how he lobbied Henry Paulson Jr., the Goldman Sachs CEO, to build the company’s new headquarters across from ground zero. “If my company hadn’t been started here, I don’t think there’s a chance we would have been anywhere near as successful,” Bloomberg says. “This is where the best want to live and work. So I told him, ‘We can help with minimizing taxes. We can help with minimizing your rent. We can help with improving security. All of those kinds of things. But in the end, Hank, look, this is about people.’ ” The city’s workforce has plenty of admirable qualities, but even Bloomberg can’t spin the fact that Goldman got more than $1.65 billion in city and state “help” in the deal. So he digresses into a rumination about his generation of financial executives. “Hank is a business friend,” Bloomberg says. “Most of the guys that run these big firms, they’re my age. And because of my company, there’s a credibility. They respect somebody who’s not a politician, who’s trying to get things done. And I think it’s fair to say they like the progress in the city.”

Bloomberg is so chipper that he dissolves into laughter when I tell him about a recent conversation with his oldest daughter, Emma, about the benefits and drawbacks of growing up rich. She’d written a check to a charity from her own account. The charity saw her last name and asked why the amount wasn’t bigger. “That’s not very smart,” Bloomberg says, cackling. “Emma is going to run a very large foundation of her own some day.”

Bloomberg’s path to City Hall was paved with philanthropic checks. Not, of course, in the sense that he bought enough goodwill to be elected mayor in 2001, although the money helped. The connection is more complex, and more interesting.

Much of Bloomberg’s long record of philanthropy is purely charitable, given out of the kindness of his heart. And out of habit. Money was always tight when Bloomberg was growing up in Medford, Massachusetts, a blue-collar suburb. The Bloombergs owned their own home, but Michael’s father, William, worked seven days a week as an accountant at a local dairy to feed his family of four. Michael’s view of money was formed early: It was a tool, to be imbued with no emotional attachment whatsoever. And the acquisition of money was inextricably tied to hard work, nothing else. Throughout the fifties, though, William regularly wrote small checks to the NAACP. “He said it was because discrimination is against everybody,” Bloomberg recalls.

After graduating from Johns Hopkins and Harvard Business School, Bloomberg came to the city in 1966 to work at Salomon Brothers. The firm set aside money that each employee was required to donate to charity. “Michael grew up at Salomon knowing something about the Catholic societies, the policemen’s fund, the firemen’s fund,” says Morris Offitt, a fellow Salomon partner and Hopkins graduate who became one of Bloomberg’s good friends. “Guys on the trading desk were always helping to support the city through their different involvements. Michael learned more about the city from the trading desk of Salomon than he could have learned anywhere else.”

Bloomberg was fired by Salomon in 1981 after losing an internal power struggle, but got handed $10 million on his way out the door. He used $4 million of it to launch a computerized financial-information company that became Bloomberg L.P. In 1994, with the company a phenomenal success, Bloomberg hired Patti Harris to organize and expand his largesse, focusing on education, public health, and the arts. Some money was directed to people and organizations with social connections to Bloomberg, like the Irvington Institute for Immunological Research, whose fund-raising was spearheaded by his neighbor Lauren Veronis. Other Bloomberg gifts have gone to causes traceable to his upbringing and heritage. “Being charitable is an important part of Jewish identity,” says Joan Rosenbaum, director of the Jewish Museum. “And Michael has been an extraordinarily generous supporter of the museum since 1988.”

Besides prolific contributions, Bloomberg used another tool to become a force in philanthropic and social circles. In 1986, he bought a $3.5 million, five-story townhouse on East 79th Street and hired interior designer Jamie Drake, who fitted it out with velvet-covered chairs, billowing draperies, French Savonnerie carpets, and landscape paintings in ornate frames. He hosted frequent dinner parties there, which were often pretentious in their unpretentiousness: Bloomberg made a point of serving fried chicken and coleslaw. He created an eclectic salon where Beverly Sills might be seated next to a cancer specialist. Typically, he’d make a few remarks to loosen up the room, then work his way around the table quizzing the guests on current events and their work. “He has a very quirky sense of humor, and he’s very flirtatious,” Sills says. “And it doesn’t matter if you’re old, young, chubby, skinny. If you’re female, he can get your attention.”

Out of Bloomberg’s social activities, he began to construct his political being. Meanwhile, he was growing bored with his work at the company. “I knew he wanted to do something with his life besides making money,” says his friend Barbara Walters. “This was not a man who used his money because he was going to take us all out on a yacht.”

Bloomberg has given well over $150 million to Johns Hopkins, his alma mater, with much of it directed to the school of public health—which in April 2001 was renamed the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Alfred Sommer, the dean, remembers long dinners with Bloomberg, debating the mogul’s next move. According to Sommer, “He said, ‘The company is going to be a going concern whether I’m here or not, and I need another challenge, and it’s not building another company. I don’t need any more money. Where can I make a difference?’ ”

Paul Schervish, a professor at Boston College, doesn’t know Bloomberg directly. But he’s studied him in great detail. Schervish is an expert on the psychology of the wealthy. “Bloomberg is an entrepreneur, and for many of them, it’s a difficult thing to view yourself as lazy or profligate,” Schervish says. “Money, to many entrepreneurs, is a statement of their moral rectitude. Bloomberg had conquered the business world, but he still had in his soul this command to use his talents and his will in another arena. And entrepreneurs are looking for a place where there is more demand than supply. In his case, more demand for a good mayor than there is supply.”

As mayor, Bloomberg hasn’t wheeled out the tired cliché about “running government like a business.” He’s simply incorporated a lifetime of business-world friends, contacts, and beliefs into the choices he makes for the city. He’s not interested in using his position to enrich his friends, or himself. What unites Bloomberg and his inner circle is their view of the city as a product to be marketed.

Bloomberg first met Dan Doctoroff in the late nineties, when Doctoroff was soliciting contributions for his New York Olympics committee. In 2001, Bloomberg recruited the former investment banker to be deputy mayor for economic development. “Before I took the job, we agreed that we had to look at the city the way you would look at the problem in the private sector,” Doctoroff says. “So within the first few weeks, we were able to get McKinsey to agree to help us do a huge pro bono study of New York’s competitive position. In many ways, the work that resulted from that formed the strategic plan that we’ve been pursuing for the last four years,” Doctoroff says. As a result, Bloomberg has pushed to exploit New York’s edge as a tourist destination—a major rationale for luring the 2004 Republican convention and the 2012 Olympics—and as a potential center for biotech firms, leading to the recent announcement of a city-backed bioscience campus near Bellevue. Since he and Doctoroff saw affordable housing as the city’s greatest immediate need, Bloomberg has promised 167,000 new units.

Other major first-term initiatives drew on Bloomberg’s relationships, not any deep-seated ideology. After defeating Mark Green in November 2001, Bloomberg recruited his Johns Hopkins public-health-school friend Al Sommer to screen applicants for city health commissioner. Sommer recommended Dr. Thomas Frieden, whose highest priority was reducing cancer caused by cigarettes. The mayor-elect didn’t just hire Frieden to be his health commissioner; he signed on for the first crusade of his first term. If there’s a second Bloomberg administration, the uproar over the smoking ban could quickly look quaint: Sommer says Frieden is gearing up to fight AIDS through more aggressive tracking of sexual partners.

Bloomberg enlisted his friend Stanley Shuman, managing director of Allen & Company, to help on several fronts. Three years ago, Shuman was one of Bloomberg’s three appointments to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, which is supposed to be spearheading the rebuilding of ground zero. Bloomberg also appointed Shuman, along with two other friends from the mayor’s corporate days, Gerald Levin (Time Warner) and Thomas Murphy (Cap Cities/ABC), to raise $9 million for the ceremonies that commemorated the first anniversary of the September 11 attacks.

The same three—along with gossip columnist and Bloomberg charity-circuit buddy Liz Smith—were appointed to the board of the Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City. The city-sponsored nonprofit agency had existed since 1994 as a sleepy, low-budget operation called Public Private Initiatives until Bloomberg appointed his longtime friend Steven Rattner, a managing principal in a private investment firm, as the head of the fund, and charged him with increasing philanthropic donations to the city. “He just called me up and told me to do it,” Rattner says. The Mayor’s Fund has raised nearly $52.9 million—at least $6 million of it Bloomberg’s—and channeled money to everything from the NYC Leadership Academy, which trains new principals, to eye exams for summer-school students, to a statue of Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese.

“Ninety-nine percent of the people with Mike’s résumé would have failed dismally at the mayor thing,” Rattner says. “He happens to be the one guy who has come to understand the political system well enough that he can function within it. And Mike didn’t do anything with the money, really, before running for mayor that would have given you any idea he’d be good at being mayor.”

Like Bloomberg, Rattner long ago soared past his parents’ tax bracket. “It gets harder, frankly, to have perspective on what goes on in the real world,” he says, “because your life changes and you operate in a certain way where you’re just not taking your dry cleaning to the cleaners anymore. But it’s true of most public officials, no matter their net worth, that they live in a bubble. They’re not operating in the real world any more than Mike Bloomberg was operating in the real world. But you’re trying to elect a guy who you think has compassion and cares and really wants to be better, even if he can’t possibly imagine how tough it would be to live in Bushwick in some five-story walk-up.”

Rattner’s faith in Bloomberg has lately become useful in an old-politics sort of way. Rattner has long been a staunch and influential Democrat; his wife, Maureen White, is finance chair of the Democratic National Committee. But in June, Rattner convened a meeting with some of the city’s biggest Democratic donors, including venture capitalist Alan Patricof and John Sykes of MTV. Bloomberg didn’t need their donations, of course. But depriving his Democratic challengers of their cash would be nearly as effective.

Toni Goodale, the socialite, professional fund-raiser, and loyal Democrat, knows Rattner well but wasn’t invited. Yet her long friendship with Bloomberg, a neighbor, was enough to hamper one of his Democratic challengers. “I’ve been supporting Gifford [Miller] since he was a baby,” Goodale says. “I was one of Kerry and Gore’s major, major fund-raisers; I raised hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars for each one. I think Gifford is great, and he could be a terrific mayor—someday. But he knows we’ve been friendly with Bloomberg. My daughter works for the corporation counsel—for Michael Cardozo, who was my kindergarten boyfriend—and in effect for Bloomberg. So when Gifford asked for help with fund-raising, I said no.”

Frank Ombres is standing on West 34th Street, grinning broadly as thousands of his happy union brothers pour out of the Hammerstein Ballroom after a raucous event that’s part press conference, part TV-commercial shoot, and part union-hall blowout. Moments ago, Mike Bloomberg was onstage, bopping tentatively as “Welcome to the Jungle” screamed from the loudspeakers and carpenters and glaziers chanted “May-uh Mike! May-uh Mike!,” their enthusiasm stoked by the city’s humming economy and an open bar paid for by Bloomberg 2005. Turning his company into an international powerhouse earned Bloomberg the respect of his corporate peers. But nothing satisfies the ego of a pencil-necked plutocrat like soaking in the cheers of a theater full of burly construction workers.

Ombres is secretary-treasurer of Laborers Local 731, and after the rally, he’s telling a story about meeting Bloomberg in a slightly different setting. “He had us over to his house a couple months ago,” Ombres says. “All the union leaders. That was pretty cool. It’s a fancy place, but he’s a regular guy. He put on a good spread. And he’s come through for us. All we want is work and new members, and he’s got construction going for the next 50 years.”

Bloomberg’s charitable giving, like his dinner-party guest list, has changed, too. The number of groups receiving money from Bloomberg has swelled from nearly 600 in 2000, when he first ran for mayor, to 843 (totaling $140 million) in 2004. The mayor says the growth is a reflection of his extensive travels around the city, which introduced him to even more worthy organizations. Bloomberg also claims that giving to a wider array of causes—from stem-cell research to the Harlem Congregations for Community Improvement to his ex-wife’s pet organization, Puppies Behind Bars—is an attempt to shield him from criticism that he’s playing favorites for political purposes.

What’s intriguing, though, as well as psychologically resonant, is that as Mayor Mike takes, Citizen Mike gives. When he took office, Bloomberg faced a city-budget deficit of $6 billion. He balanced the budget through higher property taxes and cuts to city agencies, spread equally with the exception of the Police and Fire Departments. After Mayor Bloomberg tried to slash the budgets of dozens of arts groups, Citizen Bloomberg sent checks to many of the affected organizations. “It’s not as if they get cut from one place and get added to the other,” Patti Harris says. “He doesn’t mix up private philanthropy with the city’s budget.”

But the practice seems to contain elements of guilt and strategy. The effect of Bloomberg’s personal largesse has been to shield him from being seen as a heartless budget-cutter, to buy off dissent. He also avoids angering friends who sit on cultural boards and the museum-going public whose votes he needs: See, I’m not really a Republican.

Harris, who ran Bloomberg’s philanthropy machine when he was a private citizen, has become a key figure in City Hall since Bloomberg was elected. As deputy mayor for administration, she oversees the Department of Cultural Affairs, the parks department, and the Mayor’s Fund. But her role demonstrates the gray areas created by the mayor’s wealth, and how his wealth has inevitably become entangled with his political power. Last spring, Harris harangued executives of arts agencies that receive city funding for personally contributing to Gifford Miller’s mayoral campaign. “The mayor is a loyal friend and he expects loyalty from his friends,” Harris says. “It’s that simple.”

Bloomberg’s purely political contributions have been even odder as he’s tried to buy support for New York around the country. Democratic opponents flay him for giving $7 million to the Republican convention that renominated George Bush, but Bloomberg can at least argue the event was a successful marketing tool for New York. Because of his blatantly expedient jump to the GOP, Bloomberg lacked a traditional political network and was forced to invent one out of his own wallet. Yet the checks he’s written to Senate and House Republicans and the national party haven’t paid off terribly efficiently. Kentucky congressman Hal Rogers took Bloomberg’s $5,000, then voted against additional Homeland Security money for the city. Locally, Bloomberg’s checkbook diplomacy has brought some unpleasant consequences: The mayor’s $250,000 gift to the Independence Party bought him a city ballot line but also the embarrassing embrace of noxious anti-Semite Lenora Fulani.

“It gets harder, frankly, to have perspective on what goes on in the real world,” says Bloomberg friend Steven Rattner, “when you’re just not taking your dry cleaning to the cleaners anymore.”

Ask Bloomberg what’s surprised him most about being mayor, and he says, “The politics. That’s the disappointing thing. You try to convince them to vote for something, and there is, ‘What’s in it for me?’ That is depressing. The level of analysis that is done when you see laws created, whether it’s the city or state or federal level—it’s much more horse-trading than analysis.”

Bloomberg says this with a straight face, making it hard to tell whether it’s arrogance, naïveté, or simply another reminder that he still sees the world from a billionaire businessman’s perspective. But he’s certainly learned how to play the game.

A full-size school bus has been painted white and cut in half, its rear roof and sides removed to turn it into a customized rolling stage. The bus sits on Dyckman Street, in the heart of Dominican New York, on a steamy August morning, draped with MIKE FOR MAYOR banners, directly opposite Bloomberg’s uptown campaign headquarters. Inside, there are tables full of sanchoco, mofongo, rice, beans, roast chicken. There are baskets loaded with Bloomberg campaign buttons, with a choice of four Latino national flags—Dominican, Puerto Rican, Panamanian, Trinidadian. There are lanyards with laminated cards identifying volunteers, supervisors, elected officials. There’s Fernando Mateo, former Lower East Side carpet salesman turned freelance political Latino, one of a huge, multiracial cast of formerly Democratic advisers and consultants whose primary value to the Bloomberg-campaign payroll seems to be that they’re not working on a Democratic mayoral campaign.

More subtly, there’s the merengue band. Its members are wearing blue T-shirts with the Mets logo on the front and BLOOMBERG 05 on the back. The shirts are souvenirs from a Bloomberg “volunteer night” at Shea Stadium. The Bloomberg campaign claims 30,000 volunteers. They weren’t all treated to a ball game at Shea, of course, but the campaign makes plenty of other goodies available.

It all adds up. As of July, the last time his campaign was required to file disclosure reports, Bloomberg had spent $23 million. And that’s before the major TV ads and direct-mail blowouts begin in October. Bloomberg’s reelection spending should top the record-setting $75 million he shelled out in 2001 (“The same press that says I’m spending a lot of money then raises its ad rates!” Bloomberg says). But what’s astonishing about the campaign is less the big bucks than the precision with which they are spent. Every dollar seems to have a purpose, from customized buttons and placards for every conceivable ethnic-pride parade to a more ominous, Big Brother–ish effort: the most sophisticated computerized voter file ever used in a municipal election.

“Should I tell you everything about your home life now?” Kevin Sheekey asks. Bloomberg’s campaign manager says he’s joking. Sheekey’s desk at the center of Bloomberg reelection headquarters on West 40th Street is flanked by five flat-screen computer monitors. On this morning in August, Gifford Miller released his latest Democratic-primary TV ad; hours later, Sheekey dials up and watches a digital version of the ad, a capability even the Miller campaign doesn’t have. The campaign’s most potent gadget, however, is the voter file, assembled, at a cost of more than $3 million, by mining consumer databases to identify potential Bloomberg voters. In Sheekey’s view, the mayor remains the underdog because he’s running as a Republican in a town with a five-to-one Democratic registration.

Bloomberg’s big spending also buys endless rumors about the nefarious ways he’s alleged to be using his money. In August, the Times interviewed voters who’d been on the receiving end of “push-polling”—calls disguised as opinion surveys that are really attempting to sway opinion by circulating derogatory information, in this case about Freddy Ferrer. One voter quizzed her caller and was told the call originated in Denver. Bloomberg’s campaign polling firm, Penn, Schoen & Berland, has an office in Denver. But so do lots of companies, and it’s surely a coincidence. “We don’t do push-polling,” says Bloomberg-campaign spokesman Stu Loeser.

Sheekey learned the political game as an aide to Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was always scraping for campaign cash. He joined Bloomberg in 2000, and it took him time to adjust. “I remember when I was trying to find new office space in Washington, D.C., for Bloomberg L.P.,” Sheekey says. “We’d found a few floors in some buildings, and he wasn’t happy with them. He said, ‘Well, why don’t you just buy a building?’ And I said, ‘We’re in downtown Washington; there aren’t a lot of buildings that can be bought.’ He said, ‘Well, just buy an old building. Maybe an old embassy or something.’ I said, ‘Well, there really aren’t any buildings like that downtown.’ And he looked out of the window of the car and he said, ‘How about that one?’ And he pointed out a building which was a closed bank building which I had walked past every day to work and had never noticed. In the end, our actions put the building on the market, which it hadn’t been, and someone else overpaid so much that they never had the money to fit it out. The building still sits there. He just sees things that people don’t see.”

Maybe. Or maybe Bloomberg is simply willing to spend whatever it takes to get what he needs.

Bloomberg waves off the argument that he wouldn’t be mayor if he wasn’t a billionaire, and says he wants to be reelected purely on his first-term record. But he’s unwilling to run on a level campaign-spending playing field—an acknowledgment that without his money, Bloomberg might have an actual contest on his hands. Abstractions like the long-term health of democracy don’t interest him. “What’s the argument to run a risk?” he asks. “If you really believe that you’re making a difference and that you can leave a legacy of better schools and jobs and safer streets, why would you not spend the money? The objective is to improve the schools, bring down crime, build affordable housing, clean the streets—not to have a fair fight.”

The New York area is currently in the middle of a boomlet of megarich politicians, with Bloomberg in City Hall and Jon Corzine trying to move from the U.S. Senate to the governorship of New Jersey. Corzine is embroiled in a sex-and-loan scandal, but Bloomberg has, so far, managed to move from private life to public office while holding on to his dignity. If he’s able to maintain his reputation as an effective, well-liked mayor through a second term, he just might inspire other captains of industry to follow him into the political arena. Which could bring in new ideas, or turn City Hall into a fat-cat preserve. Perhaps, if the Democrats have learned anything from the current tycoon-mayor experiment, they should start looking around for a technocratic billionaire who’s willing to stay in the party and run in 2009.

Bloomberg rests his silver-cuff-linked shirtsleeves on a scuffed conference table inside City Hall and talks about how eager he is to take on next year’s $3 billion deficit. “Look, the more complex the job, the more satisfying it is if you do it correctly,” he says. “And I had a $6 billion deficit coming in.” Will he erase this one the same way, largely through higher property taxes? “No,” Bloomberg responds immediately. “There are ways to do more with less. Keep in mind, we’ve reduced the size of the city workforce by 15, 16,000 people. We’ve cut $3 or $4 billion out of the city budget, some of it by more efficiencies, some of it by finding alternative funding sources, some of it by finding alternative ways to satisfy people’s needs, rather than just doing what we did before. There’s always a habit of just continuing to do it. Because change—you can get criticized for change. You don’t get criticized for continuing. You remember Pete Seeger, ‘The Big Muddy’? You don’t get criticized for that. You do get criticized for trying something new.”

Bloomberg seems to make up for budget cuts out of his own pocket, a practice born of both guilt and political calculation.

If there remain any doubts that Bloomberg is a liberal, his referencing of the ex-commie folksinger should erase them forever. But Bloomberg’s real religion has always been pragmatism. One warm November night last fall, Bloomberg went out to Cambria Heights, Queens, for a community meeting. After brief and unsurprising remarks touting his administration’s record on crime and education, the mayor opened the floor to questions. A woman named Anne Miller wanted to know when the weeds along Linden Boulevard would be cleared. “How does ‘by Monday’ sound?” Bloomberg replied crisply, drawing applause. Sure enough, the weeds were gone within days.

Attend any of these forums with Bloomberg—he’s held more than 80 in the past three years—and it’s hard to take seriously the charge that he’s “out of touch” with regular folks. Stiff and awkward? Sometimes. But whether he’s poring over 311 statistics, or answering dozens of e-mails from strangers each day, or touring booming neighborhoods on Staten Island and then instigating legislation to tighten zoning regulations, or insisting on personal responsibility for improving the school system, Bloomberg registers and responds to the concerns of common folks as if he were a one-man complaint department.

Yet the charge that he’s out of touch isn’t wrong on the macro level—and in some ways Bloomberg is determined to stay out of touch. On the big choices—particularly the direction of economic development in the city—when Bloomberg believes he’s right, nothing’s going to change his mind. “You can’t lead from the back,” he says. “You can’t go and try to please everybody. We have a democracy, not a republic. The Norman Rockwell picture I’ve always loved is the guy in his overalls standing up at a town meeting. But that’s not what we have. If on November 8 I’m lucky enough to win, I want to thank the voters and thank the campaign workers. But I also want to say to all elected officials, ‘By doing the right thing, you can win. You should stand up and do what’s in your heart and not worry about what’s politically correct.’ ”

As personality traits, Bloomberg’s granite self-confidence and moralism are attractive. But second terms are notoriously plagued by arrogance and overreaching. A massive physical transformation of the city is under way and would only pick up speed if Bloomberg were reelected. He has set in motion a torrent of huge construction projects that will bring sweeping changes to dozens of neighborhoods. Prospect Heights in Brooklyn will be dwarfed by Bruce Ratner’s arena-and-apartment-tower complex. The Brooklyn Heights waterfront will get hotels and parks. A new Bronx Terminal Market has begun, and Willets Point in Queens will get a new Mets stadium and 48 acres of development to replace the current chop shops. It’s hard to argue with thousands of units of new housing in Greenpoint and Williamsburg. And New York is never going to be a quaint village. But many of Bloomberg’s projects threaten to erase the pockets of human-size living that remain. It’s here that Bloomberg’s billionaire perspective, his attraction to bigger as better, can be disquieting. One of the enormous challenges for a second term would be for Bloomberg to impose thousands of acres of new residential and commercial space on the city without it looking as if downtown Atlanta had been dropped in the middle of Brooklyn.

When he was elected, Bloomberg did many of the standard things to distance himself from his previous life. He resigned from the boards of cultural institutions, including the Met, Lincoln Center, and the Jewish Museum, and from most of the country clubs to which he belonged. He did not, however, put his 72 percent ownership interest of Bloomberg L.P. in a blind trust. The city’s Conflict of Interest Board ruled that Bloomberg had to recuse himself from daily decision-making at the company but that he could continue to participate in any talks about selling it. Though rumors continue to surface that a sale would follow on the heels of Bloomberg’s reelection, he says there are no active negotiations.

When Bloomberg leaves office, in either 2006 or 2010, he’ll take the estimated $7 to $9 billion windfall from the sale of Bloomberg L.P. and devote himself to philanthropy. “I look at Bill Gates,” he says. “He’s a guy I used to be critical of because he didn’t give away a lot of his money, and now he’s giving away a fortune, and he’s doing it very intelligently. I don’t know that I would do exactly the same things, but he’s got a process, he’s got smart people.”

Bloomberg says he’s in no hurry to retire. “My private life is still pretty much the same in that I’m a workaholic,” he says. “I never took a lot of vacations. I’d rather be at work. I’ve been to Vail once in three years. I haven’t been to my house in London in five years. Bermuda, I’ve been there twice in six months, maybe. It’s close by, there’s good golf, people are nice, and it’s a multicultural, interracial society.”

Which is one of the strange and wonderful things about having Michael Bloomberg as mayor. In Bermuda, his neighbors are Silvio Berlusconi and H. Ross Perot. In New York, he lives in one of the city’s costliest Zip Codes. But he enjoys both places for their diversity. If he’s mayor for four more years, will his legacy be a stronger, equally diverse city—or a city that’s ever more like Mr. Bloomberg’s rarefied neighborhood?