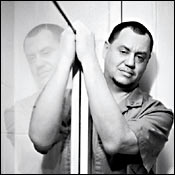

It’s the strangest thing – Mitchell Rothken is smiling. Not one of those languid, halfhearted smiles people sometimes force themselves to make to be polite, or when they’re trying to let you know they’re holding up under difficult conditions. This is a big old ear-to-ear, feeling-it-down-in-the-belly grin. Not the kind of expression you see a lot in prison.

Rothken is sitting on a plastic chair in a dirty little cubicle on Rikers Island, wearing a gray Department of Corrections jumpsuit and generic-looking white sneakers without laces. Three guards hang within earshot. Electronic jail doors relentlessly beep, squeal, and clang. Small groups of prisoners shuffle back and forth in the hallway. There is a constant, low hum of machinery. At one point, a deafening alarm sounds that seals the building and sends a team of officers in full riot gear running to the cafeteria to respond to a food fight.

But Rothken barely seems to notice. In the midst of this noisy, uncomfortable, and impossibly inhospitable setting, he is pouring out his heart. This husband and father and shomer shabbos president of his son’s yeshiva is sitting in prison telling me in vivid, copious detail the story of a great, doomed romance. A romance that eventually destroyed his once-thriving real-estate practice, forced him to surrender his law license, drove a stake through the heart of his twenty-one-year marriage, humiliated his three teenage sons, and earned him three to nine years in state prison for possession of stolen property.

The love of Mitchell Rothken’s life was a topless dancer he’d met at Scores, a 35-year-old blonde with all the requisite equipment named Kymberly Barbieri.

“She was like no other woman on earth,” he says, getting visibly excited talking about her, even now, in prison. “I really loved her. She had my heart, my soul, and my mind.”

Over the course of their four-and-a-half-year relationship, Rothken built a life with Barbieri. They became so close, he says, it was like they were married. Except, of course, that he already was married.

When news of Rothken’s indictment for stealing millions of dollars of his clients’ money first broke, the Post ran the irresistible headline FAMILY-MAN LAWYER ADMITS SECRET LIFE WITH SEXY STRIPPER. But they didn’t know the half of it. Yes, he had showered Barbieri with extravagant gifts, including several cars, a house in Westchester, and a $6,000-a-month three-bedroom, three-bath Greenwich Village apartment. But they never actually consummated their relationship. And along with clothes and jewelry and stays at the Delano in Miami Beach, he paid for a nanny for her two small children. “I lived a certain way and had a certain standard of living, and that’s what I gave her,” Rothken says. “It was only a reflection of how I felt about her.”

And when she shared her dream to run a club of her own, he opened one for her on St. Marks Place called Siren. It was named, of course, for the seductive temptresses of Greek mythology who lured sailors to their death. Rothken put more than $2 million into Siren and attempted to run the club as her partner – all while trying to keep his real-estate practice afloat and fulfill the obligations of his family life in Fresh Meadows.

It was the financial burden that made his precariously balanced worlds finally come crashing down. Rothken was a successful real-estate attorney, but not that successful: Much of his real-life fantasy was financed with his clients’ money – nearly $3 million he was supposed to be holding in escrow accounts.

“I was dancing as fast as I could,” he says, “but I knew I was sinking.”

Incredibly, he was the only one who knew. Even after one of his clients’ checks bounced, and he blew the whistle on Rothken by going to the district attorney, Rothken’s family was utterly in the dark about his secret life. It wasn’t until they were in court for his bail hearing, and the prosecutor recited the charges against him, that his wife, Shonnie, first heard the name Kymberly Barbieri.

So why would a man do this? How does a guy with an accounting degree and a law degree, an observant Jew with a rabbi for a father-in-law, go so completely off the rails? You may think the answer is obvious, but you’d be wrong. Especially since Rothken and Barbieri never even had sex. Not Bill-and-Monica-style sex, not heavy petting, nothing. Even though they did, on many occasions, Rothken claims, sleep together naked in the same bed. It was what Rothken calls “infidelity without adultery.”

In truth, despite the enormous price Rothken has paid for his extraordinary lapses in judgment, his feelings about what’s happened to him are wildly ambivalent. When he talks about how sorry he is that he’s hurt his wife and how bad he feels about his kids, he certainly sounds sincere. But then there’s that smile – the irrepressible grin he wore not only each time I saw him in prison but at his sentencing as well. There he was, being led into court in handcuffs and leg irons, smiling as if they were about to set him free rather than send him upstate.

What was he so happy about? I knew he was taking anti-depressants, but this was not about being medicated. And then it struck me. Sure, he was terribly sorry for all the pain he’d caused, but at the same time, he still didn’t really regret the choices he’d made. “I needed to do this,” Rothken says.

“I had it, and I went with it,” he says one morning, snapping his fingers and imitating Jackie Gleason delivering the well-known line from The Honeymooners.

“I’ll tell you how sick I was,” he says unabashedly. “When everything was starting to slip away, I was thinking it would’ve all been absolutely worth it if things between Kym and me had worked out.”

In the early nineties, Mitchell Rothken decided he wanted to be a player. He wanted to be a guy people looked at and talked about, a guy who was out every night at the clubs and bars with a beautiful woman on his arm. He developed what was virtually an addiction to nightlife, and for the better part of eight years, he was deliriously happy – including almost all of the time he was with Barbieri.

“You remember the scene in GoodFellas when they walk into the nightclub with their dates?” Rothken asks one afternoon in prison. “That’s what it was like for us at Scores. Whenever we showed up, we always got the best table and the best girls.”

Rothken went to Scores several times a week and spent several thousand dollars a night on his friends and clients and himself. “It was beautiful,” he says. “There was this mystique about the place and the girls. And when I went there, I was the man.”

Rothken’s obsession with strip clubs and topless dancers began routinely enough. At first, it was simply a part of doing business. It was a way to entertain clients, close a deal, or attract new accounts. Of course, it was also fun.

The year was 1993. And Rothken, a graduate of Fordham law school, where he’d met his wife, was working for the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac). The position enabled him to get to know the key players in New York real estate. In 1995, he capitalized on his connections and opened his own practice.

“Mitch was one of the toughest attorneys in that business,” says real-estate lawyer Andrew Albstein, who’s been his friend since law school. “At Freddie Mac, he got to know all the borrowers and all the properties, and he was disliked because he did his job so well. Believe me, you’d love to have him represent you.”

Rothken’s nightlife accelerated when he went into business for himself. “It got to the point where I’d be spending four or five thousand dollars a night a couple of times a week,” he says. “And on special occasions, it could go north of ten grand. But I was making the money back. It was an investment. A lot of these guys, the bankers, were never exposed to this kind of thing. They’d be drinking champagne all night with a beautiful girl sitting on each knee. So when it came time to do a deal, who were they going to give the business to? Me or the guy who took them to Peter Luger? And yes, I paid for prostitutes for clients many times.”

Rothken’s business was primarily the B-level real-estate market – transactions that involved small-to-medium-size residential apartment buildings in the outer boroughs and upper Manhattan. “A lot of these guys hired Mitch to get an edge on someone in a contract negotiation,” says Albstein. “Even if it meant flirting with the ethical line. He was their hired gun, often used to screw other people, and if he did it well, there’d be high fives all around.”

But the Scores scene was much more to Rothken than a place to show off for clients or escape the confines of family life. “It’s weird, but it’s almost like he made a second family at Scores,” says Sarah Hirsch, one of half a dozen strippers he befriended there and at VIP over the years. He helped them with their problems, he listened when they needed someone to talk to, and he didn’t demand anything – including sex – in return.

In an over-the-top expression of this bond, Rothken invited several of the dancers – including Hirsch, Barbieri, her two sisters, and her mother – to his sons’ bar mitzvahs. “His wife thought I was a client,” Hirsch says casually. “I’m used to the unusual, but I have to say that this was pretty weird. But Mitch doesn’t think like everybody else. He said Kym was one of the most important people in his life and he wanted her there on such an important day.”

He also used his legal talents on their behalf. “When I first met him, my house was in foreclosure, and he got involved and I never had to worry about it again,” says Hirsch. “He took care of everything, and he never charged me. He’s a really, really nice person. We went out together, we went away together. I could go crazy, and he never judged me. He’s my best friend.”

In September 1996, Rothken was sitting at his regular table in the restaurant section of Scores when a dancer friend introduced him to Kym Barbieri. She was dressed in a long, clingy gown with spaghetti straps – the dancers’ uniform at Scores when they’re not onstage – and Rothken was smitten. She danced for him, and then they spent several hours talking (the tab for this kind of time from a dancer could easily reach $1,000 without the tip).

A few nights later, Rothken was back at the club, but Barbieri wasn’t there. “It was like high school,” he says. “You know, when you go on a date and the girl’s friend tells you later she really likes you. So then Kym and I had a long phone conversation, and she was all bubbly and giddy that I called.”

They arranged to meet at the club the following Thursday. Barbieri brought pictures of her kids. “I remember thinking it was so cool that she was so into her kids and that she thought so much of me that she wanted to show me their pictures.”

After a few more giggly phone calls, they made a lunch date. Barbieri went to Rothken’s office in jeans and a loose sweater and very little makeup. It was the first time he’d seen her in daylight. “She looked adorable, like a college girl.”

And then they began to see each other regularly. Barbieri had been complaining about how hard it was not having a car, so one day near the end of October, Rothken took her to a friend’s dealership in Connecticut. “She had no credit, so I put $3,000 down for her on a used Acura Integra, and I got her a $10,000 loan, which I guaranteed, from a friend who has a finance company. At Christmas, I paid off the loan for her. She said it was the nicest thing anyone’d ever done for her.”

A short time later, the car was broken into, so Rothken had her trade it in for a Honda Passport that he simply paid for. “We’d been going out about four months,” he says, “and we were still just holding hands, kissing a little, and hugging.”

The next defining moment came when Barbieri hysterically showed Rothken an eviction notice she’d received. She said her husband, from whom she was supposed to be separated, had failed to pay the rent and she was being kicked out of her apartment. Rothken worked his legal magic and managed to actually get her some money to move out.

At that point, in the summer of ‘97, almost a year after they’d met, Barbieri moved back to St. Louis. This, of course, could’ve ended things between them had Rothken been less obsessed. But while she was back home, he helped her with expenses, persuaded her to get a real-estate license, and was FedExing her salamis, knishes, and other goodies from the Second Avenue Deli.

“When she decided to come back,” he says, “I took it as a message from God that there should be something between us.”

Rothken said he’d find her an apartment, which they both knew meant he would pay for it; instead, he rented her a house in White Plains. He wrote a check for the security deposit, and from that point on, they were, he says, “off to the races.”

Rothken was now fully committed, emotionally and financially. He got her a job at Citi Habitats, and they’d meet for lunch almost every day. But she hated the job. It was too much of a hassle, so she quit and enrolled at Westchester Community College. Rothken paid her tuition. She wanted to be a teacher.

Since she was no longer dancing, he tried to get her set up as a civilian: He helped her open a checking account, got her insurance, and cleaned up her credit. All this time, he was buying her gifts: jewelry, furs, clothing. And when she complained that the rented house was too small, he bought her a $310,000 house with a big yard and a swing set.

The house is now the object of a legal battle. Barbieri tried to sell it, but Rothken got an injunction to stop her. She claims she put up the $55,000 down payment, which she had saved from dancing. Rothken says she never put in a penny.

“Here I am in jail, with no money, and she’s selfishly fighting me and lying and trying to sell the house.”

Not long after Barbieri moved into the house in 1998, people started questioning Rothken about what he was doing. “I knew she was important to him, and I knew he got her a straight job where she didn’t have to take her clothes off,” says Laurence Gluck, a friend and business associate of Rothken’s. “I certainly felt things were spinning out of control. There were rumors that they weren’t having sex, but frankly, I didn’t want to know. I thought it was odd when he bought her the house, that that took it to a whole new level. I feel terrible for his wife and kids, but this is the oldest story in human experience. It’s simply a story of a guy falling in love.”

Unrequited love, as it turns out. “I was nearly 40 when I met Kym,” Rothken says. “So it’s not like I was some adolescent who needed to get laid on the first date. I just rolled with it.”In fact, he showed uncharacteristic restraint. It’s not like he hadn’t ever sought sexual gratification with other women who were part of his extracurricular nocturnal life. Still, with Barbieri, he says, there was always the promise of sex to string Rothken along and exploit him financially.

Barbieri denies this. “I never led him on,” she told me from St. Louis, where she’s now living again. “I know he had romantic feelings for me, but I told him many times that I only wanted to be friends. And he was my best friend, but nothing more.” (Best indeed. It was very friendly of Rothken, for example, to pay for Barbieri’s new breast implants when her old ones began to leak.)

“Trust me, as much of an idiot as I appear to be over this, I’m not that big an idiot,” says Rothken. “There were lots and lots of things she said to me over the years that led me to believe this was going to be a permanent hookup. I thought we were spiritually and emotionally connected. And there was always the promise of sex and romance. But as it turned out, she was a liar who was playing me the whole time.”

One year after Barbieri moved into the Westchester house, in the middle of 1999, her husband died. Rothken says he paid for the funeral, although she didn’t want him there, and to fly members of her family in from St. Louis. Barbieri didn’t want to see Rothken for a while following her husband’s funeral. He was angry, but he figured she was going through a rough time. When they did start to see each other again after the summer, it was, for Rothken, the beginning of the end.

Perhaps he knew, at least on some level, that if his relationship with Barbieri was ever going to become a romantic one, now was the time. To cement their connection, Rothken agreed to indulge Barbieri in what he calls her lifelong dream – owning a bar. Originally, it was supposed to be a small, neighborhood kind of place, but as the plans began to take shape, the project turned into a full-scale New York club.

Rothken found a space on St. Marks Place, and he began spending what would turn out to be more than $2 million on the club. He had an ownership agreement drawn up that gave him one third, and the other two thirds were evenly split between Barbieri and her mother. There were problems right from the start, of course, and by the end of the summer of 2000, Barbieri had thrown her mother out of the business (which hadn’t even opened yet) and shipped her back to St. Louis.

Worse, however, from Rothken’s point of view, was that Barbieri was telling everyone it was her club and creating the illusion that she was a rich girl from Westchester. “She was becoming the little darling of her own social circle and flirting and fucking around with all sorts of people,” Rothken says.

Finally, in October 2000, shortly before the club was going to open, Rothken lost it. Accompanied by armed guards, he seized the bar at 6 a.m. on the day after Yom Kippur. He had the locks changed and served Barbieri with legal notice he was cutting her out of the business and personal notice he was cutting her out of his life. He opened Siren himself on November 4, and for a brief moment, it was actually hot. Zagat said, “This beautiful new supper club seduces the hip and trendy.”

Rothken says that at this point, Barbieri became frantic, leaving him dozens of voice mails denying everything and telling him he had it all wrong. Within a matter of weeks, Rothken caved. She got him on the cell while he was at a Knicks game with his sons on a Sunday night. The next day, he made a date to see her.

“She said she knew she was wrong and now she wanted to give me everything I wanted,” Rothken recalls. “She said she was ready for a monogamous adult sexual relationship and she wanted to go away together. Now she was chasing me.”

Despite everyone’s telling Rothken he was nuts if he gave her another chance, he didn’t listen: “On a Monday night – in fact, it was January 15, Martin Luther King Day – I had her meet me at Siren. We went over our understanding, and I told her she couldn’t betray me again. We had the best night ever. We were kissing and hugging all night long. We closed Siren and went out for breakfast. Then we went back to the apartment. We didn’t have sex. She said she wanted to wait until we weren’t wasted. She wanted it to be special. I really wanted to believe her.”

They went to the Delano in Miami Beach for Valentine’s Day, and it was a disaster. Nothing had changed. When they returned to New York, things began to unravel. A mutual friend told Rothken that Barbieri was involved with the manager of Siren, a guy she had persuaded him to hire. Rothken went insane, but he quickly had much more serious problems.

In April, he went with his family, as they did every year, to the Eden Roc hotel in Miami Beach for Passover. Shortly after arriving, he got a call from his bank. There was a problem with a check he’d written at a closing the week before: There were no funds to cover it. Then there was a second call to tell him there was an issue with several other checks as well.

“Suddenly, I knew I was in deep shit,” Rothken says. “The kind of clients I deal with have little patience for this kind of thing. They’re crazy about money. I told the bank I didn’t know what the problem was but I’d straighten it out when I got back. But I didn’t have to check the accounts. I knew I fucked up.”

Rothken says that because he had so much going on between his family, his practice, Barbieri, and Siren, he essentially just ran everything through one bank account. He knows it was lazy, not to mention illegal, but he claims there was no criminal intent: “If I’d wanted to steal, I could’ve taken tens of millions of dollars and I would have set up offshore accounts and been much more careful.”

Between commissions and escrow money and the like, Rothken says, there were always millions of dollars flowing through the account he used. Consequently, he figured, there’d always be enough money in there, and eventually he’d straighten it out.

He knew before he left Miami that he was finished as a lawyer. His overwhelming concern was damage control. He wanted to keep his creditors from going to the district attorney, because if that happened, everything would come out.

Lawyer John Pollok told him the best strategy was to try to work out a restitution deal with the victims, not to fight. Rothken asked for 30 days to come up with some money, and he managed to raise $300,000. But that was little more than 10 percent of what he needed. And on the thirty-first day, Alfred Groner, who took the biggest hit, went to the Manhattan D.A.

Groner’s company had sold an apartment building in the Inwood section of Manhattan, and Rothken was supposed to be holding $880,000 for him, which Groner intended to roll into another building to avoid capital-gains tax. Rothken, however, didn’t have the money.

“Rothken was a guy who was probably making $500,000 to $750,000 a year,” says Groner. “He was very good at what he did. But the guy went off the deep end. I knew he was in love with some lap dancer, but I never thought this would happen.”

Rothken told his wife he was having some business problems. He said it was a real-estate dispute and he had screwed up and was going to have to repay the money. “I didn’t see any reason to tell her at that point. Why upset her any more or any sooner than she had to be?” he says with no hint that he realizes how unbelievable this statement is.

The first time Rothken’s wife actually found out what had been going on was at his bail hearing. Shonnie, his parents, his in-laws (including his father-in-law, an Orthodox rabbi), and several members of the community had come to court to put up their houses to secure Rothken’s bail.

But when the prosecutor stood up and began weaving a sordid tale of strippers and a secret life and a love nest and all of the money Rothken had spent, everyone was stunned. They had no clue this had been going on. After the hearing, in the hallway outside the courtroom, there was bedlam: Everyone was crying and screaming at one another. Rothken’s parents were trying to defend him against the onslaught of invective. Court officers actually had to break up the mêlée. Needless to say, after what they’d heard, no one volunteered any collateral for bail.

Shonnie Rothken was devastated. She quickly arranged for a get, a Jewish divorce, while Rothken was in the Tombs. She went down there with two Hasids as the required witnesses, a scribe with a quill pen to draw up the official document, and the prison rabbi.

Rothken’s defense was eventually taken over by Joseph Tacopina, who skillfully negotiated a plea agreement. Before Tacopina interceded, the prosecutor had been talking about grand larceny and money-laundering charges, which could’ve put Rothken behind bars for more than fifteen years.

Like people who skydive or race motorcycles or go heli-skiing, Rothken needs, it seems, to push the limits. Even his time in prison has become another adventure, another walk along the edge. In the Tombs, he was placed on a floor with a variety of high-profile criminals. There were Colombian drug dealers, several killers, and a handful of other seriously violent felons.

Well, one look at Rothken and you know he might as well have been wearing a big sign on his back that said PLEASE KICK MY ASS. To make matters worse, he actually had to wear a plastic I.D. tag that screamed KOSHER in big red letters. Yet rather than suffer at the hands of the other inmates, Rothken actually thrived.

In part, this was because of the friends who came to visit him. When the inmates saw strippers coming to see this zhlubby Jewish guy, that was all it took for them to believe he had to have something going on. A couple of tabloid stories about his escapades didn’t hurt, either. He actually went to court one day and came back to find that another inmate had painted his cell. “They simply assumed I was connected,” Rothken says with a laugh. “And I didn’t do anything to discourage the idea. In fact, they called me Meyer, for Meyer Lansky.”

Turning reflective one afternoon in prison, Rothken tells me he should’ve thought about the consequences of what he was doing. “I know how badly I hurt Shonnie and the kids. But really, more than anybody else, I’ve betrayed myself.”

Though it’s clear he still has strong feelings for Barbieri, he can also get very angry when he talks about her, and repeatedly calls her a “pathological liar.”

She, of course, has a different view. “He’s tried to make me look like the bad guy here,” she says. “But the fact still remains that he’s the one who put himself in this position. He’s the one who stole the money. I had no hand in that. He wants to blame his life going bad on being involved with me, but he’s a grown man. He has to take responsibility for his own actions and for the choices he’s made in his life.”

Whatever Barbieri did or didn’t do, she’s right about Rothken’s need to take responsibility for what happened.

Rothken talks about the Hebrew concept of teshuva, which is, essentially, a combination of seeking forgiveness through repentance and a total change of mind-set and life. The idea is that just saying you’re sorry isn’t enough. You have to do much more. “I’m trying to figure out how to do teshuva,” Rothken says with uncharacteristic humility.

“I need to do it for my wife and my kids and my community. This is like a disgrace to God because I’ve not only embarrassed myself and my family, I’ve embarrassed other Orthodox Jews as well. I have to make amends to the community and to my victims, who I’ve promised to pay back.”

But a close friend thinks he has a ways to go. “I believe this kind of thing can absolutely happen to him again,” the friend says. “Because it doesn’t seem to me that he really understands what happened.”

And spending time with Rothken makes it hard to argue the point. He believes he lived every guy’s fantasy. Money. Beautiful women. Sex. Freedom. And at home, he still had his family. It was, as his friend says, like he’d found his ticket to ride and wasn’t getting off until the very end. No matter what. “I actually did what a lot of guys dream about doing but never will.”