Darnay Hoffman, self-described “attorney of last resort,” pivots across Gramercy Park North with a lot of grace for a big man, pointing out places of interest: “That pale brick pile over there? Jimmy Cagney’s co-op—I never saw him around when I was a kid, but the people in my mother’s circle knew him. That’s Janet Malcolm’s building,” he says next, a little breathily, indicating the other side of the park. “Now, she’s my idea of a great journalist.”

Which segues into why we’re hiking from Gramercy to the Village to the Seventh Avenue IRT on this steaming July morning. Hoffman—civil defender of Bernie Goetz; husband of Sidney Biddle Barrows, the Mayflower Madam; pursuer of Patsy Ramsey, whom he publicly accused of being a Monster Mom—is now appeals consultant and media spinner for Joel Steinberg, the eighties Mr. Hyde who just returned to town, to a halfway house, the Fortune Society Castle on Riverside Drive, after nearly seventeen years’ lockdown in Dannemora and Elmira. Hoffman is looking for a journalist who can shed some light on the “press distortions” that have plagued his latest, pro bono client since November 2, 1987. That was the day Steinberg’s illegally adopted daughter, Lisa, was found dying of head injuries in Steinberg’s apartment at 14 West 10th Street, just off Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. The 6-year-old was nude and had, according to examining medical workers from St. Vincent’s Hospital, a huge reddish bruise on her scalp starting at the hairline, bruises and cuts that looked like someone had socked her on the chin, and old healing marks of different colors on virtually every other part of her body.

The workers had gotten the call from Hedda Nussbaum, Steinberg’s live-in punching bag (“girlfriend” hardly conveys the relationship). Nussbaum, who resembled Sylvester Stallone at the end of Rocky II, and who was nominally responsible for raising the little girl, at first explained these away as the normal bumps and scratches of early childhood, Lisa having “fallen a lot on roller skates.” She made the call to 911 at 6:32 a.m. on November 2, mumbling incomprehensibly at first: “What is it?” the operator asked sharply. “She’s not breathing. We’re giving her mouth-to-mouth,” Hedda said. A man could be heard prompting in the background.

The first officers on the scene had trouble getting into apartment 3W, though, which was weird for a couple with a child in trouble, and when Hedda did slowly open the door, they were horrified: she had two black eyes, a split lip, the bridge of her nose was gone, and shards of bony cartilage actually protruded; she had a bandanna wrapped around her frizzled gray hair to hide spots where clumps had been torn out; she was hunched and moved painfully, like an old woman, though she was only 45. It would come to be regarded as one of the most sensational crimes of the past quarter century. Nussbaum turned prosecution witness against Steinberg, helping convict him of manslaughter and Steinberg became enshrined in New York history as one of its vilest monsters. Hedda, meanwhile, faded into the background, struggling to sell her paintings. When I tried to reach her for this piece, a friend of hers wondered if she could be paid.

“But see, those are the kinds of things the media just battens on,” Hoffman insists, puffing, as we cross 19th Street. “Nothing mitigating ever made it to the six o’clock news, or to the front pages of the News or Post.”

“Like what?” I ask, wondering what Hoffman’s game is.

“If a man my size, with a fist as big as mine, hit you in the forehead, you’d hit the floor and have a mark you’d remember,” Steinberg roared. “Howcome nobody saw nothin’?”

“Like Joel’s exemplary military record. He was a lieutenant in the Air Force, when Vietnam was heating up. He had connections to the Phoenix Program! He was a brilliant strategic lawyer in his earlier career, able to delineate weak spots in a prosecution case and build his defense almost instinctively. He had an exquisitely appointed apartment [the same one, 14 West 10th], with a bookcase filled with a leather-bound legal library, a large dog he was quite partial to, a fireplace, the wind billowing immaculate white curtains. It was hardly the urine-soaked, unlighted, dirty cave you heard about ad nauseam on television.

“And he was gone from the house for three hours, during which time Hedda could have gone for help, but didn’t. Who knows what happened between Hedda and Lisa then? Hedda was jealous … And finally, there was a medical report from the University of Pennsylvania that listed no fractures or evidence of long-term battering on the little girl. None of this got any mention in the press, who—let’s face it—tend to repeat each other’s ‘party lines’ in sensational stories like this. They’re formulaic. They’re database reporters.”

Hoffman checks my quizzical look: “All right, we want to present our side, too. And when Joel was going to be released, I volunteered to help. That’s when I arranged for that limo ride down from Elmira. Five-Star Limo. They said that all they had were big white cars. And I thought of the association with meganews events of the past: O.J.’s slo-mo chase in the white Bronco; Princess Di’s high-speed paparazzo pursuit. We’d work those simplistic associations to do some good, sending the signal that this was an important case, too—‘the O.J.-Di-Joel high-speed homecoming,’ 80 to 90 miles per hour down Route 17, those crazy TV people trying to trap us so they could set up and get something for the six o’clock feed. There are all kinds of evils in society … Do you see?”

When I later asked Joel Steinberg, during one of the three long phone interviews I’d have with him, what he thought of Hoffman’s white-limo strategy, he chortled in his old-neighborhood-guy way: “You know, Hoffman started as an actor. He didn’t always look like he does now—just kidding, heh, heh, heh. His mom was the stage actress Toni Darnay, and his stepfather Hobe Morrison had been drama critic at Variety or something. I think Darnay’s a very smart guy, but let’s say he’s a little bit, uh, flamboyant—he wants to use the media’s dumb sensationalism to make points he thinks need to be made. I guess it’s guerrilla theater, as we used to call it back in the seventies. He’s faithful to his clients, though.”

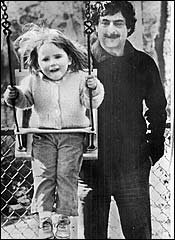

Darnay Hoffman hadn’t seen Joel Steinberg for years when he picked him up on June 30, though he’d been up to visit from time to time early on during Steinberg’s long incarceration, once taking Sidney Biddle Barrows along (Steinberg appreciated classy women). After the appeals were exhausted, he thought, there’d been no point. So when Steinberg first appeared, Hoffman was a little shocked.

The New York State Parole Department had issued him a light-green synthetic warm-up jacket and matching hat with a whitish bill, and the years away from drugs, and regular meals and hours, had partially rejuvenated him (Steinberg and Hedda were longtime addicts, and had even freebased coke all night as Lisa lay dying). Despite his grayer hair, which prison barbers had fashioned into a neo-Caesar cut, Steinberg looked tight, if not buff, for a 63-year-old, and his standard, slightly cockeyed expression was nearly normal. But a couple of big guards marched him down to the limo, scowling at it. The unspoken understanding was that Steinberg was free after serving two thirds of his mandatory sentence (8 to 25 years) because the state had no other options. Steinberg had been a fine inmate, never getting into a fight, and becoming popular with some cons by working seven days a week in the law library at Southport (Elmira), assisting them with their post-conviction legal maneuvers. So he’s free, but Pataki and the big pols can use him as a bogeyman forever, to show voters they revile monsters and support family values, too. In return, Steinberg is supposed to keep a low profile, not draw attention to himself. Slip back into New York like Bernie Goetz, weaseling back into Manhattan’s shadows.

But that wasn’t Hoffman’s plan. “I wish you’d chosen something else,” Steinberg said stoically, eyeing Darnay’s “prom ride” ’95 Lincoln Town Car stretch. He was calm, not jubilant, about leaving prison. Steinberg moved smoothly onto the gray leather seats, ignored the press circus howling around him: There were scan-dish TV trucks grazing each other despite all the state troopers; action-cam news copters thwupping the air like Apaches in Fallujah; type-A reporters bellowing: “Joel! Here, Joel! Are ya gonna visit Lisa’s grave? Are you sorry for what ya did? Look at the camera, Joel!”

The driver, though a part-timer, was very good at evading these pursuers, switching lanes when he saw a box-move coming from cooperating media vehicles, sometimes going 80 mph in bursts to outmaneuver “the flotilla,” as he’d named the press corps. At one place in Roscoe, where they’d stopped for gas, troopers had to unblock media cars and trucks so they could get on the road again: “So later, when we had to pee, rather than risk more of that nonsense, we just took some empty cognac decanters and pissed into them! [Steinberg isn’t allowed to drink, so the limo lacked its standard full bar.] I can tell you that Joel was very fastidious, and turned away—it’s a prison thing of respect. You don’t show your dick to another man unless you’re on the make.”

They spent the long ride revisiting points the Steinberg defense team had “fucked up,” as Steinberg put it, back in ’88. Ira London, his chief lawyer, came in for particular criticism: “He mighta been more aggressive with Hedda,” Steinberg growled. “He was too careful strategically, figuring the p.c. factor that was so big at the time would be too big a force to buck, everybody feeling sorry for Hedda. He screwed the time frame up, too, when I was out of the apartment, in his statements to the press. [Lisa was killed, according to Nussbaum’s testimony, because she’d been pestering Steinberg to be allowed to go to dinner with him at 7 p.m. on the night of November 1, 1987. He’d wanted to talk about an oil-well deal with a bail bondsman he was friendly with, and the girl would have been in the way. But she kept whining.]

“He [London] had his head up his ass,” Steinberg said. “I shoulda represented myself.” Another reason Steinberg was so angry was London’s reportedly huge fees. Steinberg, a man so cheap he was feeding his family with vegetables recycled from the neighbors’ garbage at the end, loathed paying Ira at all.

All the way down Route 17, Hoffman kept fielding calls from Parole. They were very specific about directives: Avoid the media; get “the package” in the goddamned Castle and stay there; pull up to 140th and Riverside and let agents escort Steinberg inside. “So there we were, humping and bumping along, when I get this message: ‘Forget 140th, they’re all over you. Speed up and go to 145th. Stop the car there!’ ” Hoffman told the driver and he maneuvered artfully, gaining a half-block on the flotilla. A sedan suddenly blocked their way. A huge agent tore the limo’s door open on Hoffman’s side, and politely asked: “Who is Joel Steinberg?” When Steinberg nodded, the agent grabbed his arm and helped him scramble over Hoffman’s legs: “They hustled him into their car and screeched away,” Hoffman remembers. “We didn’t even say good-bye … I’m ashamed to say, I felt kind of relieved.”

Darnay Hoffman lives and works out of the former Mayflower Madam’s apartment in the 200 block of West 70th Street, conveniently near the 72nd Street subway station. Convenient because he doesn’t drive. Doesn’t use a cell phone either, so it’s consequently hard to reach him, and, one would think, to do business, too: “I’m obviously not in it for the money,” he says, waving his hand dismissively at the piled cardboard boxes of client legal files that literally teeter above his head. The place is almost impassable, a beautiful white fireplace utterly hidden, tastefully framed photos of Waspy blonde kids (Sidney Biddle Barrows’s nieces) nearly obliterated by stacks of dusty detritus, and in the micro foyer, two huge boxes and a sealed tan garbage bag containing much of Joel Steinberg’s prison possessions.

Most of Hoffman’s work is civil, he says, and for small-time clients fighting losing battles with ex-spouses or the real-estate establishment. Recently, for example, there was a friend of his wife’s who’d blown all her savings on a vicious divorce case and couldn’t afford to continue—something her prosperous ex was counting on: “Darnay took her on for nothing,” Sydney recounts, “and began working back from there.”

Barrows, still smashing after all these years and now working as “a personal assistant to a hedge-fund manager” in midtown, speaks with exasperated admiration—a true testament, since they’ve been together for ten years: “Another guy, a schmuck, appealing a case he had no hope of winning but was pursuing through hubris, blowing off lawyers like J.Lo blows by husbands, offered a $5,000 deposit retainer, and Darnay turned him down because he didn’t feel the case was winnable! And we were two months behind in our [$1,500 monthly] rent! The last ethical lawyer in New York!” Barrows laughs. “Twenty years ago, who’d have believed I’d be living like this?”

“Okay, so you’re an altruist,” I try, talking with Hoffman. “What is it with all the bad guys? You’re coming on like a walker for Hitler. Is it true Bernie Goetz had a pet chinchilla that he took to club openings and let it run along the bar, pooping and nipping at people? And that he used it to break the ice with girls?”

Hoffman laughs but loyally declines to confirm the story. “Bernie’s an electronics genius,” he says instead. “When he was at Rikers, he fixed all the gadgets that the jail repair people couldn’t do anything with. He saved hundreds of thousands for New York City. The director was sorry to see him go.”

Darnay describes himself as “a libertarian,” maybe a slightly rightish Abbie Hoffman, with a master’s in marketing and an interest in “psychological motivation techniques,” which he used when he worked in TV producing some years ago.

“But what about Goetz and Steinberg?” I ask.

“Goetz represents the eccentric genius that we no longer have room for,” Hoffman explains, pushing back in his chair and involuntarily stretching his tan suspenders over his slightly seedy white shirt. “Nobody in the legal profession would stand up for him. And he was only saying what a lot of white ethnic New Yorkers were feeling: ‘The only way to save 14th Street is to get rid of all the spics and niggers!’ You don’t have to agree, but he represents the losing half of a changing racial power struggle. Look at how the Daily News’s readership has metamorphosed.

“Joel is your grandmother,” he continues. “If you let him be demonized and receive an unfair trial and distorted coverage, as happened, your relatives are next. There was a hierarchy of violence in the Steinberg household, with Joel whaling on Hedda, and perhaps Hedda whaling on Lisa, who she feared might have been replacing her in Joel’s affections.

“What if it happened this way that night: Hedda kept her cosmetics on a shelf in the bathroom where Lisa couldn’t get into them, though she kept trying; the little girl climbs up on a chair to ‘make herself up’ and thus charm her daddy into letting her accompany him to dinner; Hedda discovers her, goes into a rage, grabs her by the arm, and whiplashes her into a wall … That would account for the ‘shearing’ effect, and the fatal injury.”

Then Hoffman, a philosopher of show trials, shifts to another of his obsessions. He’s one of those who believe Patsy Ramsey is the guilty party in her daughter JonBenet’s murder. “She had a cocktail of motives—she’s depressed because she’s a former beauty queen herself, turning 40, with a husband who’s losing interest, and her beautiful child won’t do as she asks and let her relive her own triumphs vicariously. She snaps. Her husband, John, is rich and powerful and hires the best politically connected law firm in Colorado. And she out-O.J.’s O.J. by not even going to trial.”

Hoffman found this so outrageous it inspired him to become an ad hoc “prosecutor” for a while, working on a First Amendment suit the Ramsey’s nanny brought against the Ramseys and a libel suit brought by a journalist the Ramseys had said was a suspect. He also helped evolve a persuasive handwriting-analysis argument that matched the mother’s written phrasings and letter formations with those of the writer of the Ramsey “ransom note.”

The Ramseys were the opposites of clients like Bernie, Joel, and Sidney Barrows; the press accepted their status. His people, he points out, are from the wrong side of the TV monitor. They’re not chic. You won’t see them airing their views to Morley Safer or Charlie Rose, or lunching at the Fountain Room.

Hoffman curls his lip slightly. He prefers the homelier conversation of Julie Carter, his pretty intern from England, who used to work for the late ACLU activist Jeremiah Gutman; or Barry Z, a cable-TV oddity who claims he has 2 million combined viewers from his shows on Time Warner, BCAT, RCN, and MNN. (Hoffman promised Barry an “exclusive” with Steinberg. “I’m a gift from God,” Barry says. “I will get his message out unmessed with, do ya know what I mean? I’m here to help, not hurt my subjects.”)

Okay. Darnay Hoffman’s court of Miracles often gathers at the Arte Cafe, on 73rd off Columbus, in the warm weather, an Upper West Side Via Veneto scene with cheap spaghetti and latte and Darnay expounding on the Steinberg case: “Joel and Hedda were a couple of round-heeled rubes, no matter how wicked and sophisticated they thought they were being with their ‘S&M’ lifestyle. They’re from conventional Jewish backgrounds, him from Yonkers, her from Washington Heights, and like a lot of people from the seventies generation, they both thought there’d been some total break with the past. Through Rolfing, vegetarianism, mind dynamics, rock and roll, sex and drugs, they were going to remake themselves into sentient beings. Hedda had been around more, believe it or not; she wasn’t bad-looking before the title fights started. After the all-night crack-pipe sessions, the porn and brutal sex, everything escalated. Were they involved with a group-sex Story of O suburban clique he often alluded to as a ‘cult’? Maybe. Or maybe it was just fantasy. They were certainly feeding each other’s dreams, and Hedda, the supposed slave, might have been ‘topping from the bottom,’ as S&M devotees put it—that means it was her who really controlled his actions: ‘Once you’ve had a taste of the stick,’ she infamously said at one point, ‘you can’t go back.’ ”

“So you’re giving Joel a pass?” I ask.

“A man can be factually guilty but legally innocent,” he replies.

“Then who was ultimately guilty?”Hoffman, the psychological marketing student, implies it was the media, for trying to simplify human behavior. Joel Steinberg lives on the third floor of the Castle, with three other men. He hasn’t left the premises, except to go for a supervised car ride around upper Manhattan, since the great homecoming scene on June 30. He’s concerned about his safety once he’s actually in the street—“A lot of people hate my guts,” he told me. He likes the Fortune Society, he said—“It’s very nice, very modernlike, everything first-class. They’re treating me well and feeding me good. I’m in no hurry to move.”

I asked how he found his fellow ex-cons: “Good! Nice. One guy actually said he was glad to meet me, do you believe that? A piece of shit like me … ”

When I asked if coming back to New York had made him feel the death of Lisa, and the perpetual beating of Hedda, more keenly than in prison, he abruptly switched gears: “It’s not where I want to go. Of course, I’m sorry my daughter’s dead. But the medical reports showed no ‘present’ or ‘historical’ fractures or wounds. That means no history of abuse. Got it? This was from the medical officers at the University of Pennsylvania. The D.A. was trying for a very negative report, but they were honest. Do you hear? See if you can do better than those other morons do … ” Pathology reports from St. Vincent’s doctors showed “a map of pain,” as Joyce Johnson put it in What Lisa Knew, her superb book about the Steinberg case. Dr. Margaret McHugh, head of the Child Protection Team at Bellevue, who testified for the prosecution after examining all medical reports, told me: “He and his lawyers are just focusing on the parts [of the reports] that exonerate them. If it says ‘no fracture,’ they use that; if it says ‘hypodensity is present involving cortex and subadjacent white matter in the left frontal lobe,’ brain swelling, they leave it out.”

I’d heard Steinberg had done a “good” seventeen years, as opposed to Robert Chambers, the Preppie Killer, with whom Steinberg, Bernie Goetz, and John Gotti (!) had been confined at Rikers’ infirmary (“the Page-One Wing”) back in the eighties. I asked how he’d done it.

“Ever been in jail?” he snorted. “If you had, you’d know there isn’t any good time. You’re just thinking of getting out. It beats at you, and unless you’re nuts, you’re always afraid they’ll forget to open the door some day. What I did was work. When they were building the law library at the Southport facility in Elmira, I volunteered to help, because of my background. I worked seven days a week. I was always open for business. And some of those hard rocks were grateful … You know they don’t like ‘short eyes,’ guys accused of child abuse. Work. That was it … Plus, I couldn’t go sailing, could I?”

Steinberg’s stay at the Fortune Society may last into September. “Whadda I do?” he chuckled. “I decompress. I get that weight off my shoulders. I talk to the guys in here, who are having the same feelings as me … I think about my next moves.”

One of these is the possibility of a job as a host on New York Confidential, a public cable-TV show where Darnay Hoffman happens to be the attorney of record, which could start in the fall with Steinberg “learning the ropes” as an intern; it could also mean, Steinberg says, some work as a paralegal: “I’m a good lawyer, disbarred or not, and it would be wrong to throw all of that experience away … And some day, I hope to practice again.”

I ask Steinberg about the wisdom of being on T.V. if he’s as worried about people hating his guts as he’s indicated he is: “Fortunately,” he says, “they can’t get you through the ether, can they?”

“Joel is your grandmother,” Hoffman says. “If you let him be demonized and receive an unfair trial and distortedcoverage, your relatives are next.”

During our conversation, Steinberg’s voice had a spent-force quality. He made an effort to be charming, falling into the neighborhood street rhythms and idioms that men of blue-collar backgrounds of our age share: “I hear ya did some crime reporting,” he offered heartily. “I defended quite a few goombahs in my time. They put me in the wagon [from Rikers to 100 Centre Street] with John Gotti. He didn’t say anything. Wouldn’t even meet my eyes. I told Darnay to get word to him that I’d worked for the Family.”

“You never can tell what the prosecutors had in mind when they matched them in the same vehicle,” Hoffman commented later. “You’re suggesting they wanted Gotti to have Joel offed in prison?” I asked him. Darnay shrugged.

When he learned I’d once worked for the Herald Tribune in Paris, Steinberg told me about a noblewoman he’d had an affair with in France, and said that as a young, sports-car-driving roué, he’d cut the female population of Manhattan down like “wheat before the sickle,” a generational joke I hadn’t heard for a while.

But the rest of the session was spent on his military career, something he’s quite proud of, and which the press has “totally ignored.”

“You know, Joel, I looked at your letters of discharge and commendation from former officers, and didn’t see any mention of the Phoenix Program or ‘the Company,’ which Darnay told me you’d had something to do with.”

“You have to look for code words and suggestions,” Steinberg scoffed. “They don’t come right out and say, ‘Lieutenant Steinberg helped with secret bombing information.’ That’s not how they do it.”

“Well, can you give me some examples of codes, so that I can see what you mean?”

“Your mind jumps from the general to the particular,” he told me reprovingly. “You suggest a lot more than you say. It’s hard for a person with a very organized, linear, legalistic way of thinking to keep up with you … ”

I apologized for my mind, but pressed on. “Why would the major feel he had to encode an ordinary commendation with secret references?” I insisted, then read him the passage from his discharge.

“Read more,” Steinberg said, and stopped me when I got to “Lieutenant Steinberg developed an exceptional capability for personnel and facility management and supervision [that reflected] a high degree of clear thinking and decisive planning.”

“Now, if you can’t see that, it’s because you don’t want to,” he said. “You’re not being serious.”

And so our first session ended.

Our second talk was another story: “Did you ever read the Maury Terry interview in Vanity Fair? Or that bullshit book by Joyce Johnson?” Steinberg demanded. “That’s the kind of crap I always get from the press! They want me under the radar, but none of them will move their asses to get things right! I’m tired of this . . .

“Johnson … She told me she was just doing a quickie, a fast book for money. She didn’t have to break her ass doing deep research. She characterized me as a ‘supply sergeant’ in the Air Force who was ‘delusional’ about my duties! I’ll tell ya who’s delusional! She came up [in the writing business] in a strange way. Didja ever read Kerouac’s On the Road? Do you remember him banging a piece of shit in the back seat of a car on one of his trips? That was her. Yeah. Fucked and abandoned by Jack Kerouac! I’m above all this. A schlock, hack book! She knew her statements were untrue and inaccurate! Didn’t give a shit! Used me up and spit me out . . .

“Do you know what seventeen years means? I went from middle-aged millionaire to penniless old bum! I can’t even afford a subscription to Cruising World, which is not about what you might think … It’s about sailing. I like to look at the pictures. I used to take my daughter and even Hedda out [on Long Island Sound], for the peace and fresh air. That rhythm of the water. We had some good times, everybody forgets . . .

“Steinberg the monster! Nobody bothered to find anything out!”

“Well, what happened that night, Joel?” I asked. He quickly got angry.

“How do I know what happened? I wasn’t even there! Are you taking notes? … Have you read up on this? About as prepared as Sara Wallace at ABC, aren’t ya?”I thought that since we were in so deep, I’d go for broke: “You know that U. of P. medical report ordered by the D.A. but used by the defense, Joel? Where it cites all the ‘no fracture’ data and no evidence of long-term abuse? There seems to be plenty of evidence in the first part of the report that indicates massive head injury. What exactly do you think about the nature of the blows that finally killed Lisa?”

I couldn’t see him, but I could feel his outrage through the phone. He roared into it: “If a man my size, with a fist as big as mine, hit you in the forehead, you’d hit the floor and have a mark you’d remember. If I hit a little girl that way, the bruise would have been bigger than her head! I repeat, there were no present or historical bruises or fractures on Lisa Steinberg! She showed no signs of sustained abuse. What about the people at school, her friends on West 10th Street? How come nobody saw nothin’?”

I ask another question: “Why didn’t you or Nussbaum call the ambulance before the next morning? At this point, you’re still saying you just thought she had an upset tummy?”

He suddenly calmed down. He sighed: “If you read the defense summation, you’ll see that we thought she’d be all right. We hoped she would. As soon as we saw that she wasn’t breathing right, we called the ambulance. What would anyone else have done? I was a good father … ”

Brinkmanship had seemed to pass as a reaction, or tactic by the time of our last session. He began by noting our recent contretemps, but briskly brushed it off. He told me he thought we “have a lot in common,” two bright guys from the nabe who’d gone to school and “accomplished something,” and that we had the “same humor”—fatalistic, “pumpernickel on rye”—he joked, and added that I seemed “kind” beneath a raffish exterior, and wanted to “help people” in my work. Just like him. He reminded me that as a lawyer, friend, and lover, he’d been “evolving” toward a kind of gestalt position, trying to solve people’s problems in their totality, and that got misconstrued by the monolithic media liars and simplified, as Hoffman pointed out, into a monstrous totalitarianism, practiced against Hedda, Lisa, and anyone else who bugged him. He says that Hedda, for example, had told the cops she’d been responsible for whatever went on in 3W when they were first arreted:

“Then she gets with Barry Scheck [her chief defense counsel], and spends 2,000 hours being debriefed by the D.A.’s office, and she changes her story and says I did it, I struck Lisa because she was staring at me or something. And everybody buys it, because of Hedda’s condition. And—this was the worst—no notes! They kept no notes, so our side had no discovery options. Did the press pick up on this? You bet your ass they didn’t … Fair shot, right?”

Finally, Steinberg admitted that he’d “pushed” his daughter a little, “with the soft pad, you know, on your palm?,” but again denied hitting her. Did that deserve a Manslaughter 1 conviction? Seventeen years in two of the toughest slams the prison system boasts?

Steinberg was being pressured by other parolees at the Fortune Society to get off the phone:

“Yeah, yeah, my friend,” he told a man with a Puerto Rican accent. “Look, I’ve gotta go now. But remember this: I’m past my days of regressive-ism. I can’t do things I used to do. I’m shut down, shut up, and shut-in, buddy.” He finally sounded regretful.

The lawyer of last resort had several long telephone talks with me after the reporting of this story officially ended. He was naturally worried that I was going to smear him, and I was concerned that he was the Prince of Expedience, and that some of the things we’d discussed might be high-level spinning, masquerading as populist high-mindedness. But to what end?

“Nobody would help Bernie, after he lost with [Barry] Slotnick in the criminal courts. Nobody wanted to go with Joel last June, but he couldn’t have left prison without an escort like me. And who would have married Sydney?” he asked.

“You’re joking,” I said.

“I’m joking,” he agreed.

“What do you like to do most in the world, Darnay?” I asked him.

“Talk,” he said. “Analyze things. I like to sit around talking at a high level … ”

“And how do you feel about what Joel and Hedda did to Lisa?”

He didn’t answer.

And I remembered a line he’d used when I first met him: “Do you know the one about fooling some of the people most of the time, and most of the people … ”

“Yeah?” I said.

“My motto is, ‘All of the people, all of the time.’ ”