The waking hours of June 11, 2002, promised a pleasant day. On 225th Street in the Bronx, 33-year-old Jonathan Carrington got up a little late and put on a suit. He was taking a rare day off work to contest a fine for littering, after which he and his girlfriend, Gabrielle Gilpin, would ride in his black Ford Expedition into Manhattan for lunch at the Park Avalon, on 18th and Park Avenue South.

As he knotted his tie, he must have looked the part of the promising young man sketched by his résumé, which showed steady advancement in the field of human resources, culminating with his current position as a retirement-plan administrator for a major publisher of educational textbooks based in northern New Jersey.

Despite the suit, Carrington wound up having to pay the quality-of-life fine at the Environmental Control Board, but there was no point in letting that ruin a good day. He and Gilpin drove into Manhattan, and at about 12:30 sat down at the Park Avalon to what he would later testify was a full meal, including coffee, dessert, and, by his estimate, two martinis. After lunch, he decided to pick up a couple of shirts from Runway Menswear Boutique, which he knew to be on the southbound side of Park between 28th and 29th, just a few blocks away. He drove north on Park, past the store, and made a U-turn at 34th.

For Manhattan-born David M. Blank, D.D.S., diplomat in oral and maxillofacial surgery, the day began with two cups of coffee and a 50-minute drive from Nassau County into the city. By 9 A.M., he was in his office on 34th Street between Park and Lexington, facing the usual full slate of appointments for impacted wisdom teeth, dental implants, infections, tumors, and dental pain. Lunch, if he had time for it, would be a low-fat tuna sandwich from a café around the corner. The only variation from that routine came on alternate Mondays, when he spent a full day in the operating room at Kings County Hospital Centers in Brooklyn, instructing residents in oral-surgery procedures.

A steady, careful man, Blank had been married for 22 years, with one son at Cornell, another heading to SUNY-Binghamton, and a daughter in middle school. Father’s Day weekend was coming up, and he looked forward to spending it with his family on Long Island.

By 2:30 P.M., Blank had yet to step out for a break and was starting to fade. The night before, he had attended a five-hour session at Beth Israel Medical Center to renew his certification in advanced cardiac life support—a biennial requirement of his profession owing to the use of general anesthesia during surgery. Not since his residency years earlier, during a two-month rotation through the trauma unit of Kings County Hospital, had he been forced to resort to advanced cardiac life support. He recalls one incident from that time that went as far as open-heart massage and finally proved unsuccessful.

The dentist had become the lead doctor on a street corner, directing a staff of cops and passersby. Sure that his patient was going to die, he lowered his head and cried for her.

Just before 2:45, he left his office and walked toward the Duane Reade at 34th and Park to pick up a few personal items. As he was approaching the intersection, he saw a black SUV making a U-turn.

Singer-songwriter Theresa Sareo and her longtime boyfriend, drummer Ethan Hartshorn, kept musician’s hours, working late and sleeping until mid-morning. They arrived home at their Murray Hill studio apartment in the wee hours of Tuesday, June 11, after spending Monday evening with friends in Brooklyn. Though it was late, they stayed up to put together a press kit destined for a booking agent on Fifth Avenue. They usually sent publicity materials by mail, but the booking agent’s office was so close to their apartment that one or the other might as well hand-deliver this one. Perhaps Ethan could drop off the kit on his way to take the car in for repairs early in the morning. Better yet, he suggested, shouldn’t the main attraction, Theresa, hand it over in person? Yes, that was the thing to do. When they went to bed, the press kit was ready to go.

Theresa and Ethan had been living together for five years. On weekends, they made money playing weddings. During the week, they performed covers and Theresa’s original pop-rock material at lower Manhattan venues such as the Bitter End, the Bubble Lounge, and CBGB’s gallery. Over time, Theresa had achieved a level of name recognition on the local club circuit sufficient to guarantee a turnout. By the time the Twin Towers fell, she and Ethan wielded enough influence to organize a five-band benefit concert for their local firehouse, Engine 16–Ladder 7.

Theresa was still asleep when Ethan got up at 7 A.M. to deposit the car in Brooklyn, not far from the studio where he would be giving drum lessons later that day. He didn’t plan to return to Manhattan until early evening.

She remembers nothing of that morning, the last few hours of what she now calls in song her “simple life / singing for a living, with a cozy little place in the city.” Very likely she slept until 10, had a late breakfast, and spent a couple of hours writing new material—then set off on the errand that would take her across Park at 34th.

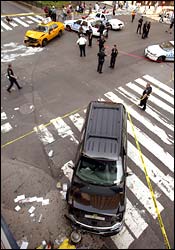

Midway into his illegal U-turn, Carrington was hit by a southbound taxi and lost control of the Ford Expedition, which slammed into the corner where Theresa, on her way home from the booking agent’s office, stood waiting for the walk signal. A chair-high metal post, installed there to protect the fire hydrant from curb jumpers, served its primary purpose. The hydrant survived. But the post also became an anvil against which the Expedition acted as a three-and-a-half-ton hammer, striking Theresa. There before the diverse New York assembly that can be found waiting to cross the street almost anywhere in the city, her body exploded at the hip, disarticulating her entire right leg at the ball socket. Jim Cushman, Theresa’s trauma surgeon at Bellevue, would later say the wound was akin to a blast injury—“as if a grenade had gone off in her pocket,” leaving a cavity the size of a large bowl in her right side.

David Blank, on his way to the drugstore, became one of the many people rushing to the scene, but he was the only one who carried fresh in his mind the lessons of advanced cardiac life support. Theresa’s internal organs were exposed. Blank slipped on a chunk of fat and almost fell. He went into automaton mode, ordering bystanders into Duane Reade for gloves while he concentrated on the ABCs he had relearned the night before: airway, breathing, circulation. After lifting Theresa’s jaw forward to open her mouth without bending her possibly injured neck, Blank leaned in close, found a pulse and felt her breath on his cheek. Good. But he needed to stanch the bleeding. Passersby rushed forward with towels procured from Austin’s Café across the street. Two police officers were already on the scene, putting on the gloves from Duane Reade. Blank directed them to use the towels to apply pressure “to basically hold her together.” A fire engine arrived. Blank asked for oxygen, a cervical collar, and IV; the engine had everything but the IV. After a couple of breaths of oxygen, Theresa began to moan. An ambulance pulled up. When Blank, the cops, and the EMTs lifted Theresa onto the gurney, her leg—attached to her body only by a small bit of flesh—was still angled down onto the sidewalk. “Better get that, too,” Blank said.

By 2:55, less than ten minutes after she had been hit, Theresa was en route to Bellevue. Blank wandered over to Carrington, who was sitting on the curb looking dazed as the EMTs tended to him. “He looked okay,” Blank says. “I mean, he didn’t look his Sunday best, but he was being handled properly.” He does not remember seeing Carrington’s female passenger.

Shaken up, no longer needed or noticed, Blank drifted away from the scene and back to his office. He washed his face and looked into the mirror. During his two-month residency rotation through the trauma unit of Kings County Hospital, he had seen people who’d been shot, stabbed, beaten, and run over. He once saw a man with the shaft of an arrow protruding from his jaw. Treating gravely injured patients in a well-equipped, fully staffed trauma center, Blank had managed with dry eyes. But this time he had been the lead doctor on a street corner, directing a staff of cops and passersby. Sure that his patient was going to die, he lowered his head and cried for her.

Meanwhile at Bellevue, Cushman, director of trauma services, was meeting Theresa for the first and, he thought, last time. He remembers the moment vividly, in part because she was conversant. “It is not common that someone comes in and is able to talk with you, and you still think they’re not going to survive,” he says. “It is very powerful, in a humbling way, to speak with that person and know in your heart that they’re not going to make it.”

At 4:15 P.M., Greg Herlinger, then a manager of Baby Bo’s Burritos, where both Theresa and Ethan worked a few shifts to help pay for recording and marketing expenses, called Ethan during his drum lesson to ask if he’d heard from his girlfriend. She hadn’t shown up for her four o’clock shift. When the lesson was over, Ethan called him back. Theresa still hadn’t turned up? No, and there had been a terrible accident on 34th and Park. Probably nothing to worry about. What were the odds that the accident involved Theresa? But Ethan had a bad feeling about it. Her route to the booking agent’s office would have taken her across Park Avenue at 34th or 35th. He hopped into a cab. Back home he saw that the press kit was gone. The television was on, as if Theresa had just stepped out for a few minutes.

Ethan began calling emergency rooms. “Do you have Theresa Sareo?” The woman who answered his second call, to Bellevue Hospital, said, “Hold on.” A police officer came on the line and asked for Ethan’s location. “She’s here—I can’t tell you any more than that—and we’re coming to get you,” he said.

If Theresa had been a few seconds later to the intersection, if Carrington had not taken that day off from work, then everything would have been different.

Bellevue was only a couple of blocks away. “I can walk,” said Ethan.

The officer was insistent. “We’re coming to get you.”

Cushman emerged from the operating room where he had stopped Theresa’s bleeding and completed the amputation. He knelt down in front of Ethan and said, “She’s stable. The worst is that she lost her entire right leg.” There was no head trauma, and her internal organs seemed to be okay. But he could make no guarantee of survival. Theresa had left nearly half of her blood on the sidewalk, blocks away.

She would remain unconscious for five days. In the meantime, she kept a busy schedule. On Wednesday, she underwent a colostomy that would not be reversed until October. Thursday her brain and her remaining leg were examined. Friday it was more major surgery, this time to inspect her internal organs and remove additional pieces of bone. Saturday she opened her eyes. Sunday she was responsive, barely, to her family and to Ethan. Monday, finally free of the respirator, she said, “I want to live.” But she did not yet comprehend the magnitude of what had happened to her. On Wednesday, Cushman broke the news, and that is when Theresa’s memory picks up again.

“You just wake up one day with one leg, you’re high on morphine, and everyone who’s ever been in your fucking life is parading by your bed telling you how ‘the angels’ saved you and everything happens for a reason.” She laughs at the diminishment of consolation. “People used to say, ‘Oh, once you start writing songs again, I can just imagine.’ Oh, can you? Can you? Because I can’t. People say the most stupid, small things because they’ve got nothing better to offer.”

After nearly a week in a coma, Theresa’s dependence on the respirator had reduced her lung capacity to the point where she lacked the breath to sing. Before her accident, she had been scheduled to perform the national anthem for the Brooklyn Cyclones on August 29, little more than two months away. After confirming with her doctors that her injuries should not prevent her from singing, Ethan suggested the Cyclones gig as a rehabilitation goal, and Theresa began working with Bellevue’s music therapist to recover her voice. Members of the hospital staff, several police officers involved with the case, and many of Theresa’s friends attended her successful performance. Cushman, now an attending trauma surgeon at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center in Baltimore, owns a recording of it. He can’t explain exactly why Theresa survived her devastating injury. “It is an unanswerable question that gets to the mystery of life,” he says. “That’s what I appreciate when I hear her perform.”

Two months after the accident, Theresa’s trauma therapist helped her into a wheelchair and pushed her to the corner of 34th and Park to confront the pole against which she had been crushed. It was—is—still bent. A hot-dog vendor named Islam Mohammad, who has worked that corner for seven years, remembers seeing her. There’s a major accident at the intersection three or four times a year, he says. He is always ready to run, as he did when he heard the tires squealing just before Theresa was hit. Dante Novoa, a doorman at 4 Park Avenue since 1980, and one of the first to call 911 for Theresa, also saw her return in a wheelchair. “I was so happy,” he says, “because when I saw her last, I saw her dead.”

Theresa’s friends see a connection between her relentless pursuit of her music career and her success in rebuilding her life after the accident. “She wasn’t even supposed to be a candidate for a prosthetic,” says Ethan. She wears one now and walks on her own. “I feel like I walk like Frankenstein,” she says, but in fact her gait is more like that of someone recovering from a knee or ankle injury. Ethan recounts an incident at a Greenwich Village restaurant: “The waiter watched her walk in and saw she was moving a little slowly. When he brought the check, he sat down with us and told her, ‘I’m going to do something real special for you.’ ”

He closed his eyes and uttered what Ethan calls “some weird little prayer.” Then he said, “Now, honey, in two weeks, your ankle will be all better.”

As they watched the waiter walk away, Theresa asked, “How much should we tip him?”

“Well, he did heal your ankle,” said Ethan.

When she’s onstage, her injury is far from obvious. Most in the audience—perhaps more blinded by her powerful voice than fooled by her prosthetic—are completely unaware of it. They see neither victim nor survivor, but a sultry lounge singer who might have stepped out of a film noir to belt out soulful renditions of classics like Burt Bacharach’s “Walk On By.” She uses the power of her left leg to rock her hips in time with the music.

Before the accident, Theresa’s reaction to the handicapped was “Man, that’s got to suck.” She was right. “It does suck,” she says. “But—and the buts become relevant—I can still do X, Y, and Z, and it turns out that is enough to sustain meaning. Life is in extremes now. It goes from the sheer joy of bringing a bag of groceries home by myself to the absurdity of watching a jogger pass by and knowing that my right leg is cremated in a box on top of my television set.”

Jonathan Carrington was charged with second-degree assault, a class-D felony. For Theresa and her friends and family, the trial registered as little more than an unwelcome distraction from the critical task of recovery. Ethan says they were not interested in revenge, in part because no one involved believed Carrington—despite his carelessness—had meant to hurt anyone. “Our focus was purely on Theresa,” he says.

Theresa attended the trial only long enough to deliver her brief testimony. Yes, that was indeed her shoe on the street in a photograph displayed by Assistant District Attorney Alberto Roig. The moment struck Carrington as cruel showmanship. “I couldn’t believe the D.A. made her do that,” he says. “Dr. Cushman had already testified in graphic detail about exactly what happened to her.” Theresa didn’t feel great about it either, but rather “a little used.”

On their way out, Theresa and Ethan found themselves at the same elevator bank with Carrington and his family. When an elevator opened near Carrington, directly across the hall from Theresa, he and his family took it. “As the doors were closing, he stared at us,” Ethan says, his eyes wide as he recounts the offense. “He had the balls to stand there and look right at us. Wouldn’t you turn away? Wouldn’t you lower your head? When I saw that, I went from not really caring about the outcome of the trial to thinking Fuck ’im. All I wanted to see was a little remorse. And I never once saw that.”

Carrington must have known his goose was cooked, and not just because Theresa had been such a sympathetic witness. During his testimony he made the awkward argument that the NO LEFT TURN sign at 34th Street did not also prohibit leftward U-turns, and tried to deflect blame on the southbound taxi that had come “bam out of nowhere” and knocked him into Theresa. On direct examination, he admitted that he had been convicted of multiple felonies at the age of 18, had served seven years, and had fabricated parts of his résumé to account for the missing time and launch his successful career. On cross-examination, Roig brought out the details of his Carrington’s prior convictions: At least one burglary was at knifepoint.

Despite these revelations, there was widespread surprise in both camps first at the guilty verdict, and then at the sentence. “We didn’t even think he was going to get convicted,” Ethan says, pointing out that Carrington’s blood-alcohol content registered below the threshold of legal intoxication, that the U-turn was a mere traffic violation, and that no one believes Carrington actually meant to harm Theresa. “And he got the max.” New York Supreme Court judge Bonnie Wittner sentenced Carrington to seven years, with no chance of release until at least April 2009.

“I’m doing this interview not for my own interests, and against the advice of my attorney, solely for Ms. Sareo,” Carrington told me across the visiting table at Franklin Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison near the Canadian border, where he is one year into his seven-year sentence. Also present was his close friend Linda Posluszny, who helped to arrange the visit and with whom I had traveled to the prison. “In the worst-case scenario, whatever I say to you could be twisted and used against me. But in the best case, maybe it will give Ms. Sareo some understanding of who I am and some more insight into what happened, and maybe even some form of relief.”

Presentable even in prison greens, and well spoken, Carrington resembles less an uneducated ex-con than a high-school English teacher. With his case under appeal, he refused to discuss the events leading up to the accident, saying only that his testimony was on record, and did not mention Gabrielle Gilpin by name, instead referring to her as his “associate.” Except in emotional moments, as when recalling Theresa’s appearance on the stand to identify her shoe, Carrington managed to avoid speaking directly about the trial as well, but it is clear that he feels he was portrayed unfairly by the prosecution. “The only two people who were telling the truth in that courtroom,” he says, “were myself and Ms. Sareo.”

During our two-and-a-half-hour meeting, Carrington’s voice and hands shook and his eyes were glossy as he discussed the frustrating collusion of physics, circumstances, and personal choices that led to the accident and made it so damaging. Anyone who has ever navigated a major New York intersection can imagine that the taxi that hit Carrington as he made his illegal turn might have been speeding, as Carrington claims. If it had been going slower, if Theresa had been a few seconds later to the corner, if the post against which she was crushed hadn’t been there—and if Carrington had not taken that day off from work, had not been there to make that turn—then everything would have been different.

Carrington seems desperate to redeem himself to “Ms. Sareo.” He says he wishes there were something—anything—he could do for her. Of his stone-faced demeanor during the trial, which offended some of her supporters, he says, “I had to take on a sense of stoicness to protect myself from falling apart.” He remembers the elevator encounter and realizes he gave offense, but says he thought his offense had been in not offering the elevator to Theresa: “I’m standing closest to the door and my mother and grandmother were pushing me in.” He says the stare that Ethan remembers was one of admiration.

He described explaining the accident to his now 7-year-old daughter, Danielle, who asked, “Daddy, what happened?”

“I was in a terrible accident.”

“Was someone hurt?”

“Yes, very badly.”

“Well, did you say you were sorry?”

In the visitation room, with other reunions in progress and the commotion of children and food and supervision, Carrington’s eyes reddened and his voice trembled. “I said, ‘Yes, I did say I was sorry.’ ” But on the advice of counsel, he never delivered any form of apology to Theresa.

Carrington is aware that to observers his silence suggested remorselessness, and that any expression of concern—even now—might strike some as insincere. But he maintains that he wanted to visit her in the hospital. “My grandmother, who recently passed away, was willing to go with me to see Ms. Sareo in the hospital, but my attorneys absolutely prohibited any contact,” he says. “My grandmother was a believer in God, and she was going to church and having people pray for Ms. Sareo, as I was, and she believed it was an accident, and she believed in the system. She told me I had to be willing to accept some punishment, and I agreed, but she never thought it would be seven years. I called her when I got out of that courtroom. Her voice was full of despair. She said, ‘Johnny, how could they? It was an accident.’ ”

In prison, Carrington knows men who are serving less time for violent crimes committed intentionally. He follows the sentencing of drivers in other vehicular cases and referred me to, among others, that of Leslie Jennemann, a Long Island resident who, after a night of drinking and dancing, killed a man in a hit-and-run, continued home to have sex with someone she had met earlier at a party, and the next day took her vehicle in for repair, claiming she had hit a deer. Convicted of second-degree manslaughter, she received a sentence of two to six years.

Even Theresa points out that Carrington was not drunk when he struck her but “impaired,” which in New York State means having a blood-alcohol content of between .05 and .07 percent. “I’m not defending him,” she told me, “but I have friends and family who drive like that and worse all the time. Have you never gotten behind the wheel after two or three drinks?”

It is perhaps a primal misjudgment of our lizard brains to suspect that someone missing a leg must be concerned with nothing more than the challenges of self-conveyance and is therefore disqualified from the creation of intellectual product and art. Ethan’s voice rises in frustration when he characterizes the attitude. “ ‘Good for you, you’ve got your own CD, that’s amazing!’ ” he says. “No, you know what’s amazing for you is that it’s going to be a kick-ass CD. Her singing is better than ever, her songwriting is better than ever, her band is better than ever. Don’t tell her ‘Good for you.’ She’s been performing since she was a kid.”

In late August, Theresa and her band began recording ten tracks for her new CD, to be called Alive Again. I attended a rehearsal and saw her perform “Take Me Down,” which includes the lines, “I wish I could walk a million miles / Or simply walk into your arms.” As she sang those lines I looked at Ethan on the drums to see if I could detect any twinge of emotion, but he was concentrating on the music, and so was she.

If one of the challenges for anyone who has worked to develop a means of expression is to transform personal experience, which is almost never directly relevant to others, into art that often is, then in this Theresa has succeeded by referring only obliquely to her tragedy, singing of grief for a lost way of life that is broadly resonant within the context of recent New York history and lends voice to anyone who has been dealt a U-turn, including perhaps even the incarcerated Jonathan Carrington.

Since the accident, friends have become acquaintances and vice versa, and every one of Theresa’s relationships has changed. “Some people are stuck where they are, which is fine, but I don’t have that luxury anymore,” she says. “I have to redefine the parameters of who I am.”

A few days after the accident, Blank spoke with Cushman and found out the odds were improving for Theresa Sareo’s survival. He considered visiting her but did not want to impose. Weeks later, he phoned her room at Bellevue and got her answering machine. “She sounded lucid, terrific, and that was good enough for me at that point,” he says. He did not leave a message. Even when he testified at Carrington’s trial, Blank did not cross paths with Theresa, though afterward she did call to thank him for his first aid and his testimony.

Their inevitable reunion had come to seem to both like unfinished business when, two years after the accident, Blank saw a woman on 34th Street near Lexington, walking slowly on what his medical training told him was a significant prosthetic leg. Beside her was a young man. “I thought, ‘This has got to be her,’ ” he recalls, “so I took a chance.” He walked up to Theresa and Ethan and introduced himself. “Last time I saw you, you didn’t look so good!” He pointed toward his office and explained how he had come upon Theresa that day. “I had just stepped out for some air and to go to Duane Reade.” He asked some detailed questions about her rehabilitation. It was going well, and she had started a support group for amputees at Bellevue. And how was the singing going? Also great. Theresa would be in the recording studio soon.

Theresa had long wanted to meet this man whose quick action helped keep her from dying on the sidewalk, but she had worried that facing him might cure her merciful amnesia about the accident. She wanted no vivid memories of the SUV, the post, or the wide-eyed faces of bystanders who thought they were witnessing her death. What a relief that Blank’s smile restored none of that. Instead, this chance meeting was yet another recovery milestone she could now put behind her.