On a beautiful friday evening recently, Senator Jon Corzine, the former head of Goldman Sachs, a man worth some $300 million, was sitting in his silver SUV on Route 1, somewhere deep in the wilds of central New Jersey. Without a GPS or a visible road sign, it was difficult to tell exactly where he was, since one stretch of Route 1 looks more or less like any other: mile after mile of fast food, strip malls, and car dealers.

Corzine, who is running for governor, was between campaign stops. After wrapping up a public meeting at Monmouth Regional High School, he had dinner at the East Brunswick Hilton. Following a salad and chicken potpie, he stopped at a few tables to shake hands—the surprised diners found him hard to place until he introduced himself.

Afterward, Corzine rolled down Route 1, navy pin-striped jacket off, toward his next stop, the Islamic Society of Central Jersey, where he delivered a talk about genocide in Sudan. During the Q&A, one man got up and said, “We are all human beings. All of us together, as people. I am a Muslim, you are Jewish … ” Corzine’s neck and face turned red, but he let the man finish talking.

“Actually,” Corzine said to him finally, with a slightly awkward smile, “I’m a Methodist.”

For a politician suffering the indignities of retail campaigning, Route 1 in central New Jersey can be a long, lonely road. And even now, more than five years after Corzine left Wall Street to enter politics, it’s still hard to understand why he chose this path. Why a man whose shoes were as impeccably white as Corzine’s once were would march into the swamp that is New Jersey politics. Corzine, after all, reigned at the richest, most prestigious investment bank in New York. And for Corzine, the Senate isn’t enough. Being governor would put Corzine in a much more hands-on, make-it-happen role. It’s an executive position, of course, and New Jersey has the most powerful governorship in the country. It is the only statewide elected office. “As governor, I’d be able to affect people’s lives,” Corzine says. “I could set an agenda that really works to make the reason I got into politics happen.”

The event that made Jon Corzine a politician took place at the end of 1998, when he was in Telluride, Colorado, on Christmas vacation. As CEO of Goldman Sachs, Corzine had worked for nearly two years to transform the legendary partnership into a public company. Fighting significant resistance from many of the partners, he maneuvered and battled to sell the idea within Goldman. Eventually, he succeeded in his call for a vote by secret ballot, which had never been done before.

With the IPO approved but still several months away, Corzine and his family went skiing. While he was away, three members of Goldman’s five-member executive committee, led by Corzine’s co–chief executive, Hank Paulson (the man he appointed and who still runs the company), staged a palace coup, stripping him of his CEO title and his power. “They worked in secret against him all during Christmas,” says someone familiar with what took place.

Corzine was devastated. Apparently, he never saw it coming. “He came back from Colorado and simply could not believe what had happened,” says a confidante.

Corzine was so humiliated that he couldn’t bear to go to the office, even though he was determined to stay on for several months to see the public offering through to its conclusion. So, according to someone who knows him well, he developed an unusual routine. He’d get up every morning, put on his suit, step into his waiting limo, and ride from his house in Summit, New Jersey, to downtown Manhattan. He’d have his driver park in front of Goldman’s offices at 85 Broad Street—and he’d work from the backseat of his car. He’d have secretaries bring whatever he needed down to him. “You have to understand,” says this person, “he’d always been a winner. He was president of his fraternity. He was captain of every team he’d ever played on. He’d become chief executive at Goldman when nobody except him thought that was possible. He’d never lost at anything before.”

The IPO had made Corzine rich, but after he left Goldman, he found himself in a painful purgatory. He began to put together an investment group to buy Long-Term Capital Management, the hedge fund that had famously crashed in 1998, almost taking the world financial system with it. “I’d gone a long way down that road,” Corzine says. But then Senator Frank Lautenberg announced he wasn’t going to run for another term, and “whether I put another zero on my net worth didn’t seem nearly as interesting or as important,” he says.

Like an athlete who suddenly finds himself out of sports, Corzine needed to satisfy his continuing hunger to compete. Part of his passion for being a trader was the competition. He also needed a public way to save face, a way to regain power. And he needed to do it in a new arena, one in which he wouldn’t be regularly reminded of his failure.

“I like to compete, and I like to win,” he says. “And being in a campaign is the most competitive thing I’ve ever done.”

Politics can be an ugly business. There is little glamour and even less of the pampering most high-level executives are accustomed to. It is no accident that few CEOs ever run for political office.

“People who know me,” he says, “know that I’m not really much of a planner with respect to my ambitions. For me, it’s always been more about seizing opportunities when they present themselves. A lot of people had misgivings about my decision to go into politics, and it was never a sure thing. But I believed it was going to work.”

And Corzine didn’t look back. “The Goldman Sachs part of his history ended when he left,” says one former colleague, “and really hasn’t been revived much except for his continuing friendship with [former Treasury secretary] Bob Rubin.”

Colleagues were stunned by how completely he’d left his old life behind, down to his emerging liberal political beliefs. “Don’t forget,” says one Goldman partner, “this is a guy who was a free-market economist.”

Soon after Lautenberg’s announcement, an interesting friendship blossomed. Corzine reached out to the crafty, powerful then-Senator Robert Torricelli, the dark prince of New Jersey politics who was investigated for ethics violations and eventually forced out of public life. When the Senate ethics committee cited him for accepting pricey gifts (but not for more serious charges), he chose not to run for reelection.

The foundation for the friendship was laid when Corzine was still at Goldman and Torricelli was a rising New Jersey congressman in search of Wall Street campaign funds.

Contrary to the tale that has been told over and over about Torricelli and several others’ cooking up the idea of a Corzine candidacy and then pursuing him, it was Corzine who pursued them. “I actually got a call saying Jon Corzine was annoyed with me for not suggesting him,” says Torricelli, who was chairman of the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee in 2000. “And the truth is, until then, the thought never crossed my mind.”

But Torricelli quickly became Corzine’s Virgil, an indispensable guide to the world Corzine wanted to enter. He advised him on whom to hire, whom to meet with, and where to spend his money. Corzine threw himself into politics with the same indefatigable work ethic he’d had as a bond trader. “We told him he’d have to meet with 100 or 200 key people around the state,” says Torricelli. “County chairs, labor leaders, party activists. And he’d have to attend every major dinner in New Jersey. Well, he saw 500 people. He did it for weeks.”

Torricelli says he has, over the years, seen lots of businessmen who wanted to run for office. “But they almost never have the stomach for it,” he says. “They’re not prepared to invest the time and the effort. I was skeptical about Jon as well. He was a farm boy from Illinois who’d climbed to the top of Goldman Sachs. I did not imagine him going to the diners and beer halls and union headquarters and bonding with the folks who make up the heart and soul of the Democratic Party.”

To Torricelli’s surprise, Corzine took to these small interactions immediately. But his early public appearances before larger groups were so cringe-inducing that Democratic Party leaders were ready to pull the plug on his candidacy. “There were several meetings,” one insider says, “where everyone pretty much agreed it wasn’t going to work. He really didn’t have a clue.” Corzine was saved only by his money and his willingness to promiscuously spend it to get elected.

As awful as he was in front of groups, he was terrific at the more up-close-and-personal encounters. He was warm, friendly, and eager to listen. He is still at his best when he is able to make eye contact. Even his critics admit that Corzine is extremely likable.

“Jon really benefited from his professional pedigree,” Torricelli says. “The people expected a distant and arrogant figure. And the contrast between their expectations and the way Jon actually was really worked to his advantage.”

Corzine bristles at even the hint of a suggestion that there was anything untoward about his relationship with Torricelli. “I was a first-term freshman senator and he was the senior senator and he was very helpful in showing me how to get things done,” Corzine says, a touch of frustration coating his voice. “He really knew how to work the halls down here. Bob is enormously articulate about the issues he cares about, and he is a really smart guy,” Corzine says. “Was he maybe too clever sometimes? Perhaps. But it was a constructive relationship on how you become effective in the Senate.”

It is one thing for Corzine to view Torricelli within a political context as “the oracle,” as one veteran pol put it, but people who know Corzine well believe that the relationship went much deeper. “There’s a whole group of us who believe that when Jon developed his relationship with Torricelli, he began to live some sort of lifestyle that resulted in the breakup of his marriage,” says someone close to Corzine and his ex-wife.

Corzine and Joanne, who’d met in kindergarten and were married for 33 years, split up early in 2002. She issued a blistering statement claiming that politics had “had a noxious effect” on their marriage.

“I still believe in family values, loyalty, and fair play,” the statement, which clearly blamed his conduct for their divorce, went on. “I had no desire to seek a separation from my husband or jeopardize the vows of my marriage, either before he was elected to the Senate or afterward … We had grown up together and, I felt, shared the same value system.”

Corzine has never discussed the breakup except in a statement issued when they separated: “While I remain deeply committed to my family, I accept my responsibility for this decision.”

Corzine had a two-year affair with a woman named Carla Katz. What makes this relationship of public interest is that Katz, a cagey political operator, is president of the Communications Workers of America Local 1034, a union that represents nearly half of all New Jersey state employees.

A few people close to Corzine believe that Torricelli engineered the coupling. “Katz was told where to be and when to be there,” one of them told me. “I think Torricelli wanted to control Jon. In order to do that, he had to bring him down to his level. He had to bring him into his political world, and Carla Katz was a key part of that world.”

But whether the former senator played matchmaker is only part of the issue. Two weeks ago, the union endorsed Corzine for governor. No surprise there. But in a somewhat bizarre public display given their romantic history, Katz introduced Corzine at the rally in a very personal kind of way, telling an anecdote about the first time they met. (She said she was expecting Gordon Gekko, and instead, “I found myself shaking the hand of a slightly rumpled, bearded guy.”)

“Jon is like your uncle,” says a friend. “If your uncle happens to bebrilliant, intenselyambitious, and very rich.”

This episode opened the door for at least one Jersey newspaper, the Bergen Record, to mention their relationship in print for the first time. Up until then, none of the papers had reported on the Corzine-Katz coupling. And it put Corzine and Katz in the position of having to face reporters’ questions about their relationship. Both refused to talk about their personal lives.

Though their relationship has been over for a while, the fact remains that one of the most important issues the next governor will have to deal with is getting the salaries and benefits of state workers under control. “No matter who the next governor is,” one insider says, “he has no hope of success if he can’t fix the state’s financial problems.”

Corzine grew up on a farm in southern Illinois in a place called Willey’s Station. It was here, watching his parents, and handling his chores before and after school, that he developed his work ethic. Most of what he’s accomplished—from playing basketball at the University of Illinois, where he was a walk-on, to his success at Goldman—has been the triumph of hard work, not just dazzling natural talent.

“My family is pretty comfortably in the mainstream of what I would call the idea of Christian benevolence,” he says, relaxing behind the desk one afternoon in his minimally decorated Senate office in Washington. Haphazardly sitting on the floor, as if he’d just dropped it when he walked in, is his green canvas weekend bag, which he uses when traveling between New Jersey and the capital.

“We were not particularly religious, but I was taught that you have a responsibility to the community you live in. And I think that these kinds of fundamental relationships with society are important to believe in and practice.”

Corzine was raised a Republican and used to hear his father rail against the government. “I would never have said it to him, but in my mind I used to think, ‘What the hell are you talking about? What about the rural-electrification program and the price supports for farms?’ Right from the start, I saw government being a huge help and support in people’s lives.”

When his draft number came up, he enrolled in the Marine Reserves and eventually got an M.B.A. from the University of Chicago. He started his business career in the futures and options market, because, he says, “I was a University of Chicago graduate who actually knew how to add and subtract and knew what a second derivative of calculus was.”

In 1975, he went to work at Goldman, in the company’s anemic bond-trading division. He was made a partner within five years, and shortly thereafter he became a member of the executive committee. “He was a hayseed when he arrived at Goldman, and he started at a low level in the fixed-income area,” says a former colleague. “But he quickly rose to handle government securities, which were the most important part of the fixed-income business, at a time when that business was taking off because of Reaganomics and the high government deficits.”

Not only was Corzine the lone rising star on Wall Street with a beard, he was the only heavy hitter who wore a sweater vest on the trading floor. (When he got the top job at Goldman, sweater vests conspicuously became a popular accessory.) But Corzine’s bookish appearance was misleading. “Like any good trader, he was always calm under pressure,” says another former Goldman partner. “But when he gets going, he has this great intensity and enthusiasm, and he drove things hard. It’s what made him effective.”

And there were times when he would, in his sweater-vest-wearing, full-beard-and-glasses kind of way, blow up. “These were never the cursing, screaming tantrums of the stereotype of a Salomon trader. But they were almost scarier because they weren’t screaming fits.” (Corzine told me he always apologized after losing it.)

Corzine’s big break came in 1994, when Goldman Sachs was going through an unusually difficult period. Following a series of trading losses, senior partner Stephen Friedman abruptly left the company along with three dozen other partners who followed him out the door, taking their capital with them.

“There was no plan for a successor, and everyone knew they had to have someone step in quickly,” says one partner. “So overnight they named Corzine to head the firm. It wasn’t something the partners went off and voted on. It happened very suddenly.”

Corzine appeared to rise to the occasion. He stopped the exodus of the partners, and within a year, according to those familiar with the situation, the company was stabilized. Several years of prosperity followed. Hank Paulson, who had been named Corzine’s No. 2, was eventually promoted to be co-chief of the firm. With Corzine and Paulson sharing power, the two often antagonistic sides of the business were equally represented—Corzine was a trader and Paulson an investment banker.

Things began to unravel near the end of 1997. Corzine had become convinced, ever since the crisis that resulted in his getting the top job, that Goldman needed to go public. And he began to push hard for this change.

“You can’t run a company with a $300-to-$400 billion balance sheet doing business in 26 countries, with all of the problems that can occur in that industry, with a nineteenth-century capital structure,” Corzine says. “We needed to protect the company.”

However good an idea, an IPO meant scrapping 130 years of tradition of running the company as a partnership. The change did not go down easy. There were many at Goldman who refused to let go of the romantic idea of the Goldman partnership, of the company where teamwork and camaraderie flourished and the needs of the individual took a backseat to the greater good.

Corzine knows that his push for the IPO caused friction with some on the management committee. But there were other issues as well. “I think things really started to unravel when Corzine began acting as if he was actually the chief executive of the firm,” says one former partner. “He began to make some decisions on his own, and in a partnership, you have to cajole and plead and convince the other partners to do what you want them to do.”

Corzine says that he is proud of what he did at Goldman. The IPO did go through, and many of the partners made as much as several hundred million dollars each—Corzine included. “It’s the kind of thing you have to do in life,” he says, as the buzzer on the wall of his office sounds, indicating that a floor vote in the Senate will take place in fifteen minutes. As we head to the basement of the Hart Senate Office Building to take the little automated train to the Capitol Building, he finishes his thought.

“You don’t acquire capital so you can stuff it in your casket when you die,” he says as we get on the train for the two-minute ride. “And you don’t acquire political capital not to expend it. You have to seize opportunities and do the right thing, even if there’s some personal cost involved. Goldman will be a lot better for what we did for a very long time.”

The people around Corzine quickly learned to use his low-voltage, totally-lacking-in-charisma personality as a way to sell him to voters. This is a guy who’s a real person, with hopes and fears and concerns about the quality of life in New Jersey and the rest of the country just like you. He’s unpackaged, unbuffed by image makers.

“Jon is like your uncle,” says a former Goldman colleague. “Only he’s not. Unless your uncle happens to be brilliant, intensely ambitious, and very rich.”

“Jon has no idea whathe’s heading for,” says a supporter, about the corruption in Trenton. “If he did, he wouldn’t be running.”

It’s not that Corzine’s not a nice guy. He is. But it’s become his official persona, his identifier, in the same way that John McCain has nurtured and sold his image as a rebel who says what he really thinks.

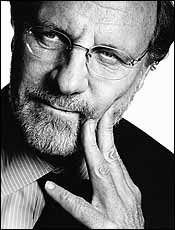

I must have been told the Corzine-beard story half-a-dozen times by people around him. It has become part of his anti-politician mythology, like his refusal to give sound bites. The story goes like this: Back in 1999, when he had just made his decision to run against former governor Jim Florio for the Democratic Senate nomination, all of the experts told him he had to shave his beard. He refused. He’d worn the beard for years. What will the voters think of me, he said to the political insiders, if I change who I am, if they see I’d do anything to get elected? Why would they trust me after that?

And there is, in fact, a genuineness about him. Kristen Breitweiser, one of the activist 9/11 widows who became known as the Jersey Girls, tells an anecdote about a photo op at one of the post-9/11 bill signings. “All of the politicians are schmoozing and trying to get into the photos to get credit. Corzine actually walked away from the cameras when he spotted the 12-year-old son of one of the widows,” she says, sounding moved even now. “He went over and just started talking to him. He asked him how he was doing. And he said he should be really proud of his mom and what she accomplished. He basically passed on the photo op just to say something nice to a kid.”

But there is this other side to Corzine as well. It’s not exactly a dark side, but there are plenty of shadows. He has an elusive, almost unknowable quality. Just when I start to think he is someone whose motives are pure (okay, not pure exactly, but at least emanating from the right place), the other side of Jon Corzine jumps out. This is the Corzine that Doug Forrester, his Republican opponent, will try to sell to the voters.

This is the Corzine who behaves, at times, as if the price of his second career were some sort of Faustian pact with the Devil. This is the Corzine who was schooled in politics by the unsavory Torricelli, and despite the uniformly cheerful denials—the Corzine camp is totally on-message about this—Corzine maintains a close relationship with him. This is the Corzine who was ready to go into business with soon-to-be-convicted felon Charles Kushner when they attempted to buy the Nets. (“I was simply trying to keep the team in New Jersey,” Corzine says, “and I won’t apologize for that.”)

And this is also the same Corzine who stood by quietly while people around then-Governor Jim McGreevey plundered the State of New Jersey—something Corzine admitted after the fact that he should have been more vocal about. This behavior alone would be enough for one to comfortably conclude that Corzine is immersed up to his folksy whiskers in the ugly swamp of New Jersey’s Sopranos-like political system. But there’s more.

New Jersey remains perhaps the country’s last medieval bastion of machine politics. There are, any of the experts will tell you, six local Democratic bosses, the warlords whose support is imperative for any successful political candidacy (the Republicans have their own group). Because of their extraordinary influence, money flows freely into their organizations. And no one has been a more fulsome contributor than Corzine. He has given nearly $1 million to a campaign committee run by George Norcross, the Democratic warlord in South Jersey. And, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Corzine has given approximately $10 million more to other party organizations around the state since 2000.

But perhaps the easiest way to appreciate just how much of a crafty politician Corzine, the anti-politician, has become is to look at the case involving his mother. In a story first reported by the Bergen Record, Corzine’s 89-year-old mother, a retired teacher who lives in Illinois, donated $37,000 to the Bergen County Democratic Organization, which is run by a warlord named Joseph Ferriero.Corzine knows the attacks from the Republicans are coming; in fact, Forrester has already run ads tying Corzine to McGreevey and Kushner. But in reality, Corzine’s only crime where McGreevey is concerned was his silence—which seemed like some sort of tacit approval. “The truth is that McGreevey and Corzine had almost no relationship,” says one Democratic insider. “They were always two ships passing in the night. McGreevey never had any respect for Corzine because he didn’t fight his way up the ladder the hard way through local politics. And Corzine never had any respect for McGreevey because he felt he had no foundation, no core beliefs, and therefore no intellectual right to be governor.”

There is also a strong public perception that Corzine used his financial muscle to squash Acting Governor Richard Codey’s hopes of running for a full term. And it’s true that, faced with a primary opponent as rich as Corzine, who had been tactically spreading the wealth for years, one would have to have a political death wish to take him on. “I believe categorically that Dick never intended to run,” says one Democratic insider. “Whether because of his family or his personal life or whatever, he never really took any of the necessary steps. He never opened up his tax records, and he hadn’t done any of his homework to prepare for a candidacy. Jon and Dick don’t really like one another, going back to the Senate primary in 2000, but Jon didn’t force him out.”

Though Forrester is not thought to be a particularly formidable opponent, the Republican National Committee has the resources—and, many believe, the will—to make the race a difficult one for Corzine. “They haven’t done much at all yet,” says one Democratic Party leader. “The big question is what their strategy will be. Do they come here and go district by district registering voters and getting them out on Election Day like they did in Ohio? Do they pump money into the campaign through the 527s like they did with the Swift Boat stuff? In other words, do they really decide to play hardball? If they do, the election could end up too close to call. If they don’t, Corzine wins by five points.”

Corzine’s people argue that corruption and political funny business are not limited to the Democrats. No one in New Jersey, they say, is walking around pining for the good old days of high ethical standards when the Republicans ran things.

And furthermore, given his wealth, he’s clearly not a threat to engage in any kind of personal corruption, like so many others entangled in New Jersey’s pay-to-play web, in which local officials are paid off for jobs and contracts. Nor, since he has spread so much money around in the form of political contributions, will he be beholden to any of the warlords the way McGreevey was.

Rather, he has gotten himself in the thick of New Jersey politics by giving, not taking. As a self-funded politician, he hasn’t accumulated debts that must be repaid. He has, however, been tarnished by appearing to buy people’s loyalty.

“His biggest strength,” one of the warlords told me, “is also his biggest weakness. He wants to make everybody happy.”

For himself, Corzine has decided that four and a half years in the Senate are enough. After spending a record-breaking $62 million to win his Senate seat (the campaign was not only the most expensive in history at the time, but it doubled the previous record), Corzine is ready to move on. He has decided he can get more done in Trenton than he can in Washington.

It is the classic risk-reward calculation of a bond trader. He has assessed the situation and decided to cut his losses to take a potentially more attractive market position. “A good bond trader,” Corzine told me one morning in his Senate office in Washington, “is able to absorb lots of information and synthesize it down to what’s going to move markets.” In other words, determine what’s most important. “Then, he has to be willing to execute.”

Corzine is now executing. “Jon always had a surprisingly aggressive trading pattern,” says one of his former Goldman colleagues. Though he won’t come right out and say it, Corzine’s time in the Senate has been disappointing, hardly worth the price of admission. (If he becomes New Jersey’s governor and this is his fifth and final year in the Senate, he will have spent approximately $33,972 a day for the privilege of being a legislator.) As a member of the minority party, indeed as one of its most openly, proudly liberal members (which places him securely in the minority of the minority party), Corzine has had to scale back his expectations.

“I’m 58 now,” he says, “and I’m the last person on every committee I sit on. I’d have to stay in Washington until I’m 80 to be a committee chairman.”

To fight the corruption that plagues New Jersey politics, Corzine has said he will relinquish some of the governor’s power by appointing an independent state comptroller to scrutinize all state contracts. His overall plan on the policy front can be described in one broad stroke: Make New Jersey more affordable. Specifically, he talks about health insurance, education, and property taxes.

This plan is actually a reflection of his core belief, which drives his behavior in the Senate as well. As one of his aides put it to me, Corzine is committed to “universal access.” That is, universal access to the American Dream—meaning everyone is entitled to education, health care, housing, and a decent wage. It is a basic philosophy that has consistently ranked him as one of the Senate’s most liberal members.

The next governor of New Jersey, however, may have only a slim chance for success no matter what he does. The problems in Trenton are worse, the experts say, than they have ever been. “You can’t choose your moment in history,” says Jon Shure, president of a think tank called New Jersey Policy Perspective. “And there’s no doubt the chickens are coming home to roost. The next governor is going to face some very serious problems.”

Structural budget gaps. Huge pension shortfalls. Soaring property taxes. A culture of corruption.

“Assuming he wins the election in November,” says a Corzine supporter, “he’s going to wake up one day next year and say, ‘What the fuck did I do?’ He simply has no idea about the kind of control the urban predators have in Trenton. And I can’t see him shooting anybody. It’s just not in his nature.”

Though the conventional wisdom says that Corzine, as a former CEO, is much better suited to be a governor than a senator, the opposite may be true. “It’s one thing to go from Wall Street and the rarefied air of Goldman Sachs to the rarefied air of the United States Senate,” says one of his closest longtime supporters. “It is quite another thing, however, to go from the rarefied air of the Senate to the muck of New Jersey politics. And frankly, it’s a real concern. Jon has no idea what he’s headed for. If he did, he wouldn’t be running. You’re talking about the kind of ethical climate where state senators represent companies appearing before state boards.”

Former governor Jim Florio, who knows firsthand how intractable New Jersey’s problems can be, nevertheless believes that if Corzine wins, he may have a shot at making some changes. “What’s different now,” Florio says, “is there’s a greater perception that failure to act will inflict more pain than acting. So while there won’t be any rose petals in the next governor’s path, this broad perception will make it easier for someone willing to take on the problems.”

Corzine insists he knows what he’ll be up against in terms of the state’s ethical and financial problems and that he is prepared to deal with them. “If you look at how my life has unfolded,” he says one sunny morning after leaving the Senate floor, “I’ve demonstrated, as a trader, as a CEO, and as a senator, that I can do a good job. But even more than that, I’ve demonstrated that I’m willing to take on the difficult battles. It would’ve been a lot easier at Goldman not to get into the fight about going public. I could’ve just stuck it out another fifteen years and accumulated a much bigger net worth.”

But there is another issue as well: Corzine’s ambition. Given the depth of the state’s difficulties, the winner in November could end up in a kind of Catch-22. If he is successful in making the kinds of structural changes necessary to fix some of the most serious problems, he may have to alienate so many people in the process that he ends up being an unpopular, albeit successful one-term governor.

That fact doesn’t mesh very well with where Corzine wants to go. The people closest to him say he has talked openly about wanting to run for the White House. He denies it. “I’m not trying to build toward something bigger, toward higher political office,” he says. He doesn’t, however, deny being ambitious.

“Of course I’ve demonstrated ambition,” he says, crossing Constitution Avenue. “But it’s never been blind. It’s always been about something other than just serving my own needs.”

Corzine says that one of his children still argues that, rather than spending $70 million on a campaign, he could just give that money to charity. But for that kind of investment, a trader like Corzine needs a bigger return.