When it comes to writing checks to the state and national Republican Party, Michael Bloomberg has been nothing if not prolific. He’s given them hundreds of thousands of dollars over the past couple of years—and this summer, his generosity has only grown. A source reports that he gave an unpublicized gift of $10,000 to each of the five Republican county committees in the city several weeks back. Then there was the $25,000 check he wrote to the Republican National Committee in July.

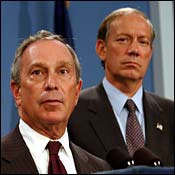

So it’s hardly surprising that some of Bloomberg’s supporters are wondering why George Pataki, who as the nominal head of the state GOP should be grateful for such largesse, has been MIA on an issue of great concern to them. Why, they’re wondering, has the governor remained silent while various Republicans around the city threaten to challenge the mayor in a primary in 2005? There’s been talk of such a challenge from former Queens City Council member Tom Ognibene, from Staten Island representative Vito Fossella, and even from former police commissioner Bernie Kerik.

Pataki could easily put an end to all this noise. “He could be saying, ‘There will be no primary,’ ” says a Bloomberg confidant. “He could be saying, ‘This is not something we want. This is not beneficial to anybody.’ But he hasn’t said anything yet.”

The problem isn’t that Bloomberg and company are consumed with worry about a Republican primary. Rather, the governor’s silence points to a larger, more urgent question: Will Pataki, who has often enjoyed the help of the mayor, ever get around to returning the favor? Bloomberg, who continues to struggle, will need Pataki more than ever if he is to turn things around in time for the 2005 election. Of course, this would require sacrifices here and there from the governor. But is Pataki prepared to make them?

The answer, it seems safe to predict, is no.

During the past year, Pataki has demonstrated an extraordinary indifference to Bloomberg’s political needs, which helps explain the mayor’s dismal numbers. In part owing to Pataki’s neglect, Bloomberg has become the mayoral equivalent of the ’62 Mets—he’s earned the lowest approval rating in the history of New York Times mayoral polls.

Pataki has another chance to bail Bloomberg out, however—in 2004. Next year is do-or-die for this mayoralty, for a host of reasons. If Pataki gives Bloomberg the assistance he needs, he could help facilitate a comeback for the mayor. If he doesn’t, it could very well demolish Bloomberg’s reelection prospects.

The mayor has good reason to be pessimistic. “Every time Bloomberg asks Pataki to throw him a life preserver, the governor happily throws him an anchor,” says City Council member Eric Gioia of Queens. “So there’s no reason to assume that Pataki will care whether the mayor sinks or swims next year.”

To understand how much Bloomberg needs the governor, look at what the mayor needs to get done in 2004. First, he has to survive another grueling budget battle. He’s already been battered within an inch of his political life by the last budget. Now, with scant services left to cut, he faces another $2 billion gap.

“Pataki’s response to the mayor’s magnanimity has been a study in ingratitude.”

Second, Bloomberg absolutely must jump-start a series of initiatives around the city, most visibly the development of Manhattan’s West Side and the rebuilding of the World Trade Center. This would create a sense of a resurgent economy, of a growing city, rather than of a city in a holding pattern.

Third, the mayor’s sweeping school reforms—which he wants to be his signature issue, just as fighting crime was Rudy Giuliani’s—will have to start showing results.

Pataki, if he’s so inclined, could help on all these fronts. On schools, he can fast-track the work of a new state commission set up to deliver funding to city schools. On rebuilding and West Side development, he can ensure that staff squabbling and spotlight-hogging don’t carry the day.

Most important, Pataki could easily limit the political fallout from another disastrous budget next year. A generous state-aid package, or some sort of tax reform, would make the mayor’s budget easier for the electorate to swallow. Imagine, for instance, if Pataki delivered Medicaid reform, helping to relieve the city of a massive drain on its finances; it would be a huge victory for Bloomberg. Or imagine if he revived the commuter tax.

So is there hope? Listen to a senior Pataki administration official: “I can assure you that the governor will not support any new taxes,” he says. “Looking nationally, the governor has to stick to his guns. The best guide to what the governor will do next year is to watch what he did this year.”

When confronted with such talk, the mayor’s aides point out that they, too, enjoy leverage over the governor that could persuade him to be helpful. Pataki “needs us as much as we need him,” says a Bloomberg-administration official. “He doesn’t want us talking about education, crime-fighting, and ground zero without him. If the governor has higher aspirations, who do you think will host his fund-raisers?”

Still, it seems certain that the two men will be more and more at odds in the coming months. That’s because their political goals are entirely different. Pataki is betting all his political capital on a future with the national party. His last years in office will be solely about burnishing his Republican credentials. Bloomberg has another imperative: getting reelected at home. Pataki, the most pragmatic and calculating of politicians, isn’t likely to squander political capital to give Bloomberg a lift.

There’s a certain poignancy to the mayor’s plight, because Bloomberg has consistently done unto Pataki as he’d have Pataki do unto him. He’s gone to extraordinary lengths to protect his fellow pol, often at great cost to himself. The depressing tale is by now well known. During Pataki’s 2002 reelection effort, the mayor, in addition to giving campaign contributions, generously suppressed all talk of tax increases. This favor cost Bloomberg dearly later; he was forced to do a fiscal about-face, telling voters that tax increases would be necessary after all.

Pataki’s response to the mayor’s magnanimity has been a study in ingratitude. Last spring, playing to a national conservative audience, the governor ruled out any tax hikes and reforms that would have helped the city. This stranded the mayor in the lonely role of an economic Dr. Feelbad, forever ladling fiscal castor oil—tax hikes and service cuts—into the mouths of New Yorkers. The mayor’s numbers plummeted. We keep hearing the familiar explanations for the mayor’s unpopularity—he’s a technocrat, he can’t connect, he bought an obscenely expensive bike at a photo op, etc. But the most important reason may be that Pataki abandoned him to face the wrath of the voters alone.

The mayor’s response to these insults has been one of restraint. Although tensions have occasionally escalated, Bloomberg has refrained from getting personal with Pataki. It’s just not his way. If things deteriorate again, the mayor may have no choice but to get angry—publicly, that is—and demand better treatment for himself and the city.

Complicating matters for the mayor, future differences will play out against the backdrop of the Republican National Convention next August. Picture this: Bloomberg is going to spend four days touring the city arm-in-arm with George W. Bush at a time of rising partisan rancor. This, a year before he asks the overwhelmingly Democratic city electorate to keep him.

The mayor’s Democratic challengers, of course, are salivating at the prospect of tying the mayor to Bush and the national GOP. Such arguments, however, could easily be neutralized if Pataki comes to Bloomberg’s rescue next year. The mayor could say, “Look, I’m not crazy about the national GOP’s ideas, but my being a Republican has allowed me to deliver X, Y, and Z to the city.”

But if Pataki abandons him again, Democrats will have an easy time turning his GOP ties into a political liability. “Much of what Bloomberg has staked his mayoralty on is his alliance with top Republicans,” says former Bronx borough president Fernando Ferrer, who is mulling a mayoral run in 2005. “If it doesn’t yield a good result for the city and for him, it will be a big problem for the mayor politically.”

Next year is the final test for one of the central ideas driving Bloomberg’s mayoralty. A lifelong liberal Democrat who joined the Republican Party just in time for the 2001 mayoral race, he’s long been convinced that his personal wealth could buy for New York City the goodwill of Republican leaders in Albany and Washington. If he invested in them, the reasoning went, then surely Republicans would return the favor and invest in the city.

But Bloomberg’s investment continues to show no returns. As this hugely successful businessman must know by now, he’s been stuck with a bum deal.