New York Democrats are, as a rule, a pessimistic bunch—and why wouldn’t they be, having lost the last three mayoral and gubernatorial campaigns in a row?—but still, you’d think that the events of recent weeks would have been cause for cheer.

On Election Day, Democrats racked up several victories with far-reaching implications for the party’s future. Dems crushed Michael Bloomberg’s bid for nonpartisan elections, suggesting enduring weaknesses on the mayor’s part. They installed a Democratic chairman in Suffolk County, long a crucial Republican stronghold. These wins, combined with other recent developments, mean that for the first time in a long while, the pieces are in place to bring about a dramatic turnaround in the party’s fortunes.

So why are many Democrats still worried? Reason No. 1 is the fact that for all its recent gains, the party is still saddled with a flaw that could hamper its long-term recovery: It lacks a strong leader at the top.

It’s become something of an obsession in Democratic Party circles: Why is the state leadership so weak? The question now has taken on a new urgency, because Democrats sense a huge opportunity. Will weakness at the top make it more likely that Democrats will revert to their seemingly natural state—squabbling, balkanized, and ineffective?

Democrats are in a better position than they’ve held for a good long while. There is an unpopular Republican in City Hall. There is a distracted Republican in the governor’s mansion—George Pataki seems to be spending more time daydreaming about a future in national politics than planning reelection; he’s unlikely to pursue a fourth term. Rudy? Giuliani wants to be president, not governor; talk about his running in 2006 seems like yet another attempt by supporters to get his name in the papers.

The point is, the GOP isn’t sure whose banner it’ll carry in the 2006 election. Meanwhile, a formidable Democrat is laying the groundwork for a gubernatorial campaign—Eliot Spitzer.

At the same time, a big realignment has occurred in New York politics—one that favors the Democrats. The Suffolk victory marks the first time that the party has controlled the three suburban counties ringing the city—Suffolk, Nassau, and Westchester. Democrats continue to severely erode the GOP’s suburban base, a key to Republicans’ grip on the governor’s office.

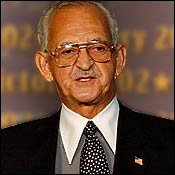

The task of pulling all these pieces together falls to the party leader—State Assembly member Herman “Denny” Farrell, the chairman of the State Democratic Committee. A tall, reed-thin, light-skinned African-American with white hair, dapper dress, and a bemused expression, Farrell was chosen in part because his calm demeanor might unite diverse interests and soothe unruly egos. He was also chosen, it should be noted, because he’s a close ally of State Assembly speaker Sheldon Silver. Many Democrats think Silver wants the party to remain irrelevant so it doesn’t compete with his Assembly power base.

As it happens, Farrell hasn’t been what you’d call an aggressive leader; critics describe him as lackluster in his duties—raising money, developing a strong message, keeping up attacks on Republicans. “Here’s the thing,” says a senior Democrat. “The state is trending more Democratic. We have been winning suburban counties. But the party structure? It’s terrible! The leadership has offered no real money or vision.”

It might seem paradoxical that Democrats are questioning their leader just as they are making gains. But some claim that these wins were delivered largely by organized labor and by other operatives and officials, and that Farrell’s leadership was not always in evidence.

Take the victory over Bloomberg’s nonpartisan initiative. Though Farrell helped unite disparate interests against the mayor’s effort, many Democrats were flabbergasted by his apparent lack of urgency in raising money to defeat it. The referendum, after all, was nothing less than an effort to destroy his party.

At one point, veteran Democratic operative Bill Lynch grew so frustrated with Farrell’s failure to raise money that he openly confronted him at a private meeting, demanding that he show leadership, sources say.

In another episode, two months before the vote, Farrell met with key elected officials and promised to bring them in to make fund-raising calls, a source said, but the leadership didn’t get around to bringing them in until about a week before Election Day. “It was incredible,” said one Democrat involved. “With their survival at stake, the state party raised less for this citywide effort than some City Council members raised for their local campaigns.”

Party leaders reject the criticism, saying that they raised and spent $400,000 to fight the proposal. It was difficult to get well-heeled donors to give, because they were afraid of offending the mayor. “If everyone had just stopped complaining about how the party did not raise the money, and helped us raise the money, then we would have had the money we needed,” says Farrell.

More broadly, Farrell brushes off criticism of his stewardship, claiming he had played an important role in recent victories: “If we were to have lost Suffolk County, I would probably be blamed for it. So I should get credit for it now.”

Farrell does seem to have recognized that it’s time to strengthen the party. He has hired a full-time fund-raiser, Jackie Brot, who recently worked for presidential candidate Joe Lieberman. And he’s planning to hire a full-time communications director. “We can always do better,” he says. “But the bottom line is, I think we’re doing pretty well right now.”

Democrats are hoping that the party leadership will use its clout to avert the same disaster that cost them City Hall last time. The 2005 primary threatens to be a rerun of 2001, when Dems, divided along racial lines, allowed Bloomberg to prevail.

“The state party will have a critical role to play in keeping Democrats unified in the runup to the ’05 and ’06 elections,” says Howard Wolfson, an operative who helped defeat nonpartisan elections and supports Farrell. “The party leader has to say, ‘If you’re running in a mayoral primary and you’re not willing to support the nominee the next day, then the hell with you.’”

No one is saying that a state chairman can assert absolute authority over a Democratic party that tends toward factionalism. But a dynamic leader can certainly enforce a semblance of unity. He can do other things, such as assemble a communications shop to provide a constant critique of Republicans.

So how aggressive will Farrell be? Asked if he would step up criticism of Bloomberg in preparation for 2005, Farrell said: “If he’s wrong, I will go after him. And if he’s right, we’ll stand silent.”

Such talk is not likely to reassure impatient Democrats. They’ve been awaiting a comeback for a long time. The party began its slide under Governor Mario Cuomo, who allowed it to deteriorate until 1994, when he lost to Pataki.

With the GOP’s stark anti-crime, anti-tax message resonating among suburban and upstate voters, the GOP under Pataki built a daunting statewide machine. Although the Democrats were pulled out of debt by former party chair Judith Hope, they were unable to mount a real challenge to Pataki.

But other forces have been changing the electoral landscape. In the suburbs, lower crime and the failure of Republicans to slash taxes have blunted the GOP assault. “The suburban economy shifted against the GOP, shattering their message as the party of tax-cutters,” says political consultant Richard Schrader. “With people of color and city Democrats moving to the suburbs, the Republican machines are losing steam.”

Suburban gains have also created a new generation of young Democratic pols and operatives across the state—a kind of political farm team that, if harnessed by a capable leader, could become a formidable statewide operation.

One school of thought holds that in the media age, only a charismatic candidate can really unite a party. With that in mind, some Democrats are envisioning Eliot Spitzer, the presumptive Democratic nominee for governor in 2006, as the next de facto party leader. Others are looking to Hillary Clinton, who has thus far avoided asserting control over the party in order to avoid riling up Silver and her senior senator, Chuck Schumer. She’s expected to grow more dominant when she’s up for reelection in 2006.

It may be that the topography of today’s Democratic Party makes it increasingly hard to assert central authority. The state party, like the national one, is more than ever a loose confederation of groups and individuals, each pursuing a distinct agenda—labor unions, interest groups, and elected officials with individual fiefdoms.

“It’s the Democratic elected officials who have the power to make the party strong,” says Manhattan state senator Eric Schneiderman. “The secret is that few of them want to.”