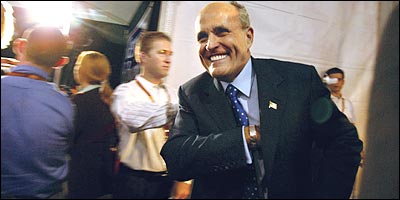

Backstage at Tempe: Giuliani spinning the third debate on NBC. (Photo credit: Stephanie Sinclair)

The Rudy Giuliani roadshow has touched down today in Macon, Georgia. As usual, it’s sold-out.

New York’s former mayor has come to middle Georgia—as he’s gone to the Pacific Northwest and the Ohio Valley; to Las Cruces, New Mexico, Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Manchester, New Hampshire—to lend his celebrity to a Republican candidate. Today’s beneficiary is Johnny Isakson, a three-term congressman representing the suburban Atlanta district that sent Newt Gingrich to Washington, who wants to be promoted to U.S. senator. In the Republican Senate primary, Isakson was considered the raving moderate because he was the only candidate willing to allow abortions in the event of rape or incest. In the general election, he’s the favorite in a race to succeed the retiring, nominally Democratic Zell Miller.

Macon has a small stretch of grand, lovingly restored antebellum mansions. This pristine tourist district is surrounded, however, by crumbling shotgun shacks. Manufacturing jobs have been deserting the city, while last year the crime rate climbed to ninth-highest in the nation. Now locals are worried that the Pentagon will shut the nearby Robins Air Force Base.

So what issues does Isakson highlight as he speaks to a luncheon fund-raiser for 200 prosperous supporters? Guns, God, and terrorism. “They don’t want you to own a firearm legally, to be able to hunt and fish or protect yourself,” Isakson says in a way that artfully blurs the line between Muslim extremists and the Democratic Party. (Does Al Qaeda really have a position on shooting fish?) “They don’t want you to worship on Saturday or Sunday in any way you want… . If you have a child, the odds are one in three the child will take a class in terrorism before they’re 12 years old.” Isakson neatly concludes this picture of Americans under imminent threat of enslavement with apocalyptic language straight out of the Left Behind novels: “We are,” he says, “in the ultimate battle between good and evil.”

At a table in the front row of the all-white audience, nodding and applauding, sits Giuliani. He’s the reason the Tuesday-afternoon event inside a boardroom at Mercer University is standing-room-only and will add as much as $75,000 to Isakson’s campaign bank account. Giuliani is, inevitably, a “man who needs absolutely no introduction,” but Isakson goes ahead and gives him a lavish one anyway. “On September 11, 2001, when our way of life and the world was threatened, Rudy Giuliani as mayor of New York City took that city to his breast, comforted the afflicted, gave hope and courage to those for the days ahead, with his sheer willpower and his sheer will,” Isakson says. “New York rose from tragic ashes to its continuing greatness. And it rode there on the back of one Rudolph Giuliani… . As a citizen of the Earth and a child of God, I’m grateful that on a tragic day in our lives Rudy Giuliani came our way.” Cue the standing ovation.

Giuliani takes the podium grinning, looking crisp and fit in a dark-blue suit, light-blue shirt, and striped blue tie. He’s supremely confident, speaking without notes in a relaxed, conversational tone. After thanking Isakson for the kind words, though, Giuliani seems to forget him completely, dwelling almost entirely on denunciations of John Kerry and the case for reelecting President Bush. He traces his unified theory of Islamic terrorism, touching on the murder of Israeli Olympic athletes, the killing of Leon Klinghoffer, and the bombing of the USS Cole—conveniently leaving out attacks that occurred on the watches of Reagan and Bush the first. “We can’t go back to where we were before, where we were during the Clinton administration, where we weren’t responding to terrorism on a regular, consistent basis,” Giuliani says, “and where we didn’t have, as an avowed goal of our government, which is what President Bush did, that we’re going to destroy global terrorism.”

The raves that greeted Giuliani’s prime-time Republican-convention speech seem to have encouraged him to speak as long as he wants. Today, though, he is nowhere near as focused as he was in August, rambling for 45 minutes. There are stiff-upper-lip platitudes from a man who was in law school during Vietnam (“War has awful consequences. People die. Young men die. It’s unfair that this person dies and this person lives”), gibes at the French and Germans (“I don’t know about Chirac, but Schröder’s a socialist. How can you get permission from a socialist to determine whether we should defend ourselves against terror?”), and a long digression into the relative manliness of Kerry and Bush as demonstrated by their abilities to throw a baseball. And, of course, there’s the hurling of the epithet liberal at Kerry. “The reason John Kerry has a hard time with these inconsistent positions,” Giuliani says, “is because if he stayed consistent with his record, there’d be a few people in Massachusetts who’d vote for him, and one or two people on the West Side of Manhattan.” He hams it up, flirting with becoming a wacky ethnic New York mascot, like Ed Koch, with his own brand: America’s Mayortm.

For Rudy to be a viablecandidate in 2008,terrorism stillhas to be thecentral issue.He could vanquish it the way hevanquishedthe squeegeemen.

Finally, after he’s interrupted by a cell phone ringing in the audience, Giuliani doesn’t so much as conclude as take a hint that maybe he should wrap it up and let people get back to work. Not, though, before he solicits questions from the audience. It takes all the way until the third question before Giuliani is asked what many are thinking: “Mistah May-ahh,” a man says, “will we be so lucky as to have you as a presidential candidate in 2008?” When the applause dies down, Giuliani is humble, humorous, and again long-winded, launching into a story about the doctor who delivered his two children and an unrelated joke about the supposed presidential scheming of Hillary Clinton. What Giuliani doesn’t say is no.

His exit is slow, as a thick stream of people ask for autographs and snapshots. Even after Giuliani climbs into a waiting SUV, three Mercer students are knocking on the tinted window. Rudy rolls the glass down and signs scraps of paper for each of the young women, the last girl holding out her pen and jogging nimbly beside the gold Chevy as it pulls away. Why was she so determined to get a souvenir from Giuliani? The eyes of Michelle Elsey and her friends all widen as if I’m an idiot. “Why?” she repeats. “He’s a hee-row!”

Out there he certainly is. New York knows Rudy is, oh, so much more: a social liberal, in favor of gun control, immigration, and legal abortion; a two-time divorcé; a bully; a brilliant, single-minded crime-buster; a cancer survivor; and a gay-friendly roommate.

At least, he used to be. September 11 transformed much of Giuliani’s image; now, on the campaign trail, Giuliani is a politician in the midst of another … evolution. He’s become President Bush’s most loyal, most visible surrogate, with only John McCain a possible challenger in pure star wattage, and an eager endorser of such right-wing nuts as New Hampshire’s Bob Smith. He’s frequently the Republicans’ designated attack dog, showing up at the Democratic convention in Boston to rip John Kerry, then again at Kerry’s debate-prep hideaway in Wisconsin, then spinning cheerfully after the debate at Tempe, as on message as Karen Hughes. For New Yorkers, there’s a cognitive dissonance in seeing him in these situations—could this be the real Rudy? Is he one of them, or one of us?

The GOP’s infatuation with Rudy shows no sign of abating. But is this a long-term romance, one that might continue into the next primary season? Or is it a passing, terrorism-anxiety-induced fling? And does he really, truly believe that he could be president?

Giuliani deflects questions about his political future by proclaiming his paramount concern for Bush’s electoral success. He also fantasizes that the Republican Party will change enough that he won’t have to. “Our party is a much broader party than it’s given credit for,” Giuliani says, sitting in a Florida hotel room between fund-raisers. “We’ll have to see what it’s like a year or two from now.”

Outside the Macon fund-raiser, Judith Pearson, a 59-year-old health-care executive, expresses her unalloyed admiration for Giuliani’s September 11 leadership; when his social beliefs are listed, Pearson literally bites her lip. “I didn’t know about that,” she says. “Being pro-life is very important to me. I’m conservative on all issues. I’d have to look at the whole picture if he were to run for president.”

Giuliani’s 9/11 halo makes all other issues look minor today. For Rudy to be a viable candidate in 2008, terrorism must still loom as the central issue in the race. Then he’d present himself as the man who could stamp out a more lethal version of the squeegee men he (temporarily) banished from the city. But Giuliani’s journey isn’t simply about raking in millions for Bush and other Republican candidates, or accumulating political chits in equally prodigious numbers. It’s a personal trip, a Republican On the Road. As he travels thousands of miles for Bush, Giuliani knows that his prospects as a Republican presidential contender will also depend in large part on how far he’s willing and able to leave his New York principles behind.

Run, Rudy, Run

And They’re Off…

By Peter Keating

Rudy’s crowd-pleasing speech at the RNC Convention starts the 2008 race. (August 31, 2004)Self-Made Mayor

By Chris Smith

Rudy Giuliani invented his mayoral persona and methods in the U.S. Attorney’s office putting white-collar criminals in jail. (April 7, 2003)American Idol

By Chris Smith

From lame-duck mayor to GOP superstar, Rudy Giuliani has in the past year become “the hottest political property” in the country. The question is not whether he will run again – but how far he can go. (September 15, 2002)

“Oooooh!”

“Aaaaaah!”

“Yeahhhh!”

Close your eyes, mix in a few screams, and you’d swear you were standing beside any Florida amusement-park thrill ride. Instead, this is the soundtrack of a West Palm Beach crowd of senior citizens swooning for Rudy Giuliani. He’s spending a Thursday in early October making appearances for Mel Martinez, until recently the Bush administration’s hud secretary and now the Republican Senate candidate; not insignificant to both roles is Martinez’s Cuban-émigré heritage. But this is an Anglo retiree audience, many from the Northeast, and Giuliani’s accent is right at home.

This press conference, ostensibly, is to announce a Fraternal Order of Police endorsement of Martinez. But the retired-cop FOP official and the Senate candidate keep their remarks short to make way for Giuliani. Except in his rallies with Bush, Giuliani plays the Mariano Rivera part at campaign events: He’s the closer. None of the TV cameras would be here today if it weren’t for Giuliani’s presence.

Giuliani’s celebrity may pull in the media, but he’s learned how to hold a crowd with masterful storytelling. Martinez mournfully mentions a Florida highway patrolman who was killed the night before, then moves quickly to campaign boilerplate. When it’s his turn, Giuliani, too, praises the officer, but he then uses the death as a starting point to tug at the crowd’s emotions—and as a natural segue to invoke the World Trade Center. “When they wear uniforms, it says something. It says they’re putting their lives at risk to protect us,” Giuliani begins slowly. “Those are very, very special people. And we thank them. The whole country found out how special they are on September 11, 2001, because they were our first line of defense when we were attacked by the terrorists. I’m gonna tell you a story about one of them.”

Giuliani recounts the last brave acts of Stephen Siller, a firefighter who ran through the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel carrying 80 pounds of gear and died saving civilians when the towers collapsed.

“And he left behind five children,” Giuliani says softly.

“Unnnnnnn,” sobs the crowd.

“It was neverclear to mehow much hisabortionposition was amatter ofconviction andhow much itwas a matterof necessity,”says FredSiegel. “Isuspect he’lldo a certainamount ofrepositioning.”

“This year, a week and a half ago, 8,000 people ran through the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, like he did.”

“Oooooh!”

“They raised all this money for our children who need education. And standing in the audience, I saw this retired firefighter. And he’s the firefighter who President Bush grabbed and took up on the pile with him—”

“Oooohh, awww, ohhh!”

“—when the president was talking to all the people at ground zero, and when he said, ‘They will hear from us!’ ”

“Ooooh!”

“And the retired firefighter said to me, ‘You tell President Bush that we’re all with him, and we want to make sure that they continue to hear from us!’ ”

“Yeahhhh!”

“To make that happen, to make certain that we carry out and finish what we—what we didn’t start, what they started when they attacked us—we not only need to reelect President Bush and Vice-President Cheney, but we need to elect people like Mel Martinez to the United States Senate.”

The applause surges. Giuliani is so smooth in moments like this that it wouldn’t be surprising to see the audience charge out of the room and demand to vote right away. But he does more than uplift. He also attacks. The Democratic candidate, Betty Castor, was president of the University of South Florida, and in 1996 suspended a Palestinian professor for making anti-Semitic remarks. Not good enough for Rudy: There were also allegations that Sami al-Arian was raising money for Palestinian Islamic Jihad. “[She] couldn’t figure out how to fire an alleged terrorist! I don’t get that at all,” he says, pronouncing alleged as if he were allergic to the word. “It’s mind-boggling! I know Mel would not have that confusion.” The next day, Florida papers run photos of Giuliani and Martinez beneath headlines with Rudy’s charge that Castor is soft on terrorism.

From West Palm, Giuliani and crew motor south to Boca Raton. He has an hour to rest before a private Martinez fund-raiser in an Embassy Suites hotel, followed by a $10,000-a-head Martinez fund-raiser in Miami. “We’ll bring in $850,000 in three events with Giuliani today,” says Martinez finance director Kirk Fordham. “It’s way more than we’ll raise with Cheney this weekend.”

Giuliani alternates being a Republican cash machine with raking in money for himself. Some of the company is downright schlocky: Last week, Giuliani was on a Learning Annex get-rich-quick bill with Donald Trump. The day he campaigned in Macon, Giuliani stopped off in Atlanta for a paid gig at the Georgia Dome, lecturing as part of something called Get Motivated! alongside Jerry Lewis.

In Boca Raton, the Embassy Suites is one of those soulless, overly air-conditioned hotels adjoining an office park just off I-95, the kind with a glass-walled elevator where all the rooms open onto a central atrium that, in the middle of the day, is as creepily quiet as a mausoleum.

Giuliani is given the Presidential Suite. Two security guards perch in the entryway. The main room is dim, with the curtains drawn and the lights off. A changing retinue of aides from the ex-mayor’s corporate consulting firm, Giuliani Partners, travels with him to political events. Today former City Hall aides Denny Young and Tony Carbonetti sit off to the sides in the shadows, along with several other silent men. Giuliani, in shirtsleeves, is on a gray central couch, an enormous cheese-and-cracker plate in front of him, untouched. When he’s standing, Giuliani is often hunched. Seated, his posture is even odder: He’s so short-waisted that his large head appears perched just above his navel.

The television is tuned to CNN. Giuliani laughs at senators Orrin Hatch and Chris Dodd. “Look at Hatch’s tie!” he says, pointing at a particularly garish combination of orange, gold, and blue. The aides in the shadows laugh, too.

Giuliani is slightly hoarse. He’d been at Yankee Stadium the night before, staying until the very end as the Yankees beat the Twins in twelve innings. “Kerry lost his voice campaigning,” Giuliani says. “I lose my voice cheering for the Yankees.” Not that he isn’t having fun campaigning. Giuliani says that as he makes his way around the country, he’s trying to do as much listening as talking. “Polls can tell you percentages, but they can’t tell you enthusiasm,” he says. “What being with people can tell you is what they’re really passionate about. The overriding thing that is on people’s minds is terror. The war in Iraq, the war on terrorism. Not just the war in Iraq, but where is it all going? What’s gonna happen next? How are we gonna deal with this? How do we get ourselves from this period of time to a period of time when things are safer?”

In New York, of course, one related issue is the shabby allocation of anti-terrorism funding. It’s easy to imagine Giuliani’s reaction if he were still mayor: Not matter who was president, Rudy would no doubt rail about the fool in the White House abandoning the city that’s suffered the most and remains the fattest terrorist target. Now, though, Giuliani hardly even sounds like a New York civilian. He meekly lays all the blame on congressional funding formulas. “The same thing happens with Medicaid, the same thing happens with welfare formulas, the same thing happens with all the distributions,” he says with a shrug. “I believe that the president should implement the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission, so that you make one exception, and that is to distribute money based on risk.”

Fine—but why has it taken Bush three years and the prodding of the 9/11 Commission to say he’ll do what’s right? “I think that’s something they’re gonna have to debate out in Congress,” he says. Giuliani wrote a best-seller called Leadership; why doesn’t he expect Bush to lead on this issue? “The administration has delivered a tremendous amount of money the city had never gotten before. Is it as much as we would like? Is it as much as we would want? No. It never is. Every one of these formulas that you’re complaining about are formulas that the Clinton administration had in place. This is more the Democratic way in which people in the city look at life. During a Republican administration, they’ll complain about this, and during a Democratic administration, they’ll forget it.” And besides, Giuliani claims, New Yorkers dismayed by his embrace of the faith-based president need to realize that Bush’s overseas offensive protects the city better than Kerry ever would.Giuliani says he speaks regularly with Bush, offering both tactical and stylistic advice. “I talked to the president about ten minutes before the first debate. I spent about a half-hour with him, with my wife, with Tommy Franks and his wife and Mrs. Bush. I told him that he should do on the debate what he had done on The O’Reilly Factor—that he should be relaxed and personable.” Which would have been better than the halting, frowning Bush who showed up that night.

The possibility of a Cabinet job—Homeland Security, say, or attorney general—in a second Bush administration hasn’t come up, yet. “Of course I’d consider it,” Giuliani says. “I think it’s very presumptuous to say—first of all, the president hasn’t offered me a job. If he did, I’d consider it, but I don’t know that I’d do it.”

“Lots ofpeople got to know me afterSeptember 11,and they feellike they havea personalrelationshipwith me,”Giuliani says.“And I thinkthey realize I care aboutthem.”

Ask Giuliani if he feels at home in the South, and the outlines of a campaign rationale are visible in his answer. “Even though I’m from New York and they’re from South Carolina, or Georgia, there are things we have in common, that we can talk about. Maybe I’ve learned that being mayor of New York City. It’s such a diverse city. You have almost the same wide range of different people in New York as you do between New York and Georgia. There are common themes that exist, whether it’s national security or the war on terror or the economy and how to handle it. There’s a way of kind of uniting people that way.”

And ask him if he envisions a day in the near future when a pro-choice, pro-immigration, pro-gay-rights Republican presidential candidate is able to win Sun Belt primaries, and Giuliani answers instantly. “Sure, it’s conceivable,” he says. “Sure. It depends on what the issues are at the time. What the overriding issues are. Is national security and the economy more important at that time? Are those the things that move people?”

Giuliani is so obviously, profoundly thrilled by his status as an icon and a millionaire that he may never want to risk stepping off the pedestal and into the cheapening scrum of running for office. Can he at least rule out a 2006 race for governor of New York (a task inevitably made harder by his current political maneuvering)? “I never rule out anything,” he says. “When the decision comes up to decide it, then I’ll decide. But this is not the right time to decide it. I’m happy where I am. I’m happy in business.”

Maybe so. It is, however, equally hard to imagine the lifelong man of action not wanting to test himself back in the arena. “Most jobs I’ve done in my life, I’ve done for about four or five years,” Giuliani says. “Mayor was the longest job I ever held. So I expect that at some point in the future, I’m gonna want to do something else. But that’s in the future.” He’s been out of public office since January 1, 2002, however. By Giuliani’s own calculations, he’s nearly due for a job change.

Giuliani’s rightward passage began at a glacial pace. He spent the sixties as a Robert Kennedy Democrat, but switched parties not long after voting for George McGovern for president in 1972. Yet despite stints working as a top Justice Department boss under Ronald Reagan and as a zealous mob-busting federal prosecutor, Giuliani’s relations with the national Republican Party have long been fraught. Some of the complications have come from trying to win elective office in a city that’s deeper blue than any mere Democratic state; some have come from Giuliani’s penchant for unpredictable, independent-minded behavior—like when he endorsed Cuomo over George Pataki for governor in 1994, or as recently as 2000, when he encouraged John McCain in the New York Republican primary before eventually joining up with the Bush campaign.

By hauling in money and free media for the GOP, Giuliani has gone a long way toward erasing the skepticism. Since 9/11, Bush and the party have needed Giuliani as much as he’s needed them. Which can create its own tensions: At times, Giuliani’s celebrity grates on Bush’s aides. He doesn’t just show up wherever the campaign asks him to go. “He makes those decisions,” says Ken Mehlman, the campaign manager for Bush-Cheney ’04, with evident annoyance. Then Mehlman is back on message. “He’s been a tremendous help to us.”

Marc Racicot, the chairman of the Bush campaign, takes a deep breath when asked if the GOP’s Evangelical base would seriously consider Giuliani for president. “I don’t know how to answer that,” Racicot says coolly. “It’s a challenge getting through primaries when you differ with the party platform.” And on issue after issue, Giuliani is on the far-left bank of the Republican mainstream. Perhaps that’s why, in Macon, Giuliani mocked the New York Times and those West Side liberals who voted for him twice.

For all his appearance of fierce singlemindedness, Giuliani has a history of taking the political temperature and making adjustments. His tough-guy act conceals a surprisingly cerebral politician. “When he ran for mayor, he really prepared,” says Fred Siegel, who has advised Giuliani in the past. “And he’s preparing himself now for national politics. He’s taking notes. When he’s ready to run, he’ll have a very good sense of what he’s doing. He reads about things, he talks to people, he gets engaged in issues. He’s a lot like Clinton in that regard.”

This presidential-campaign season has given Giuliani a chance to bond more deeply with the current GOP core. Giuliani has never been a government-hater, like the ideologically motivated activists who’ve pushed the party to the right in the past two decades; indeed, the civil-service payroll was bigger after two Giuliani terms in City Hall. But even the right-wingers vouch for his credentials as a tax-cutter. “He balanced the budget in New York, so he’s got a good story to tell,” says Stephen Moore, the president of Club for Growth, the influential, staunchly conservative anti-tax pac. “And he has done himself a world of good politically by being so aggressively pro-Bush. He’s endeared himself to conservative and moderate Republicans alike by being such a good team player. I don’t agree with him on a lot of social positions myself, but for all the talk that he’s way too liberal for the party, I’m not so sure that’s the case. The party likes heroes. And he is an American hero.” As Giuliani’s political prospects have gone national, his inner circle has stayed strikingly local. The same friends and aides who’ve been with him from his days as a federal prosecutor and a mayor—Peter Powers, Denny Young, Randy Levine, Tony Carbonetti, Sunny Mindel—either work with him at Giuliani Partners or speak with him regularly. Giuliani still talks politics with David Garth, the mysterious New York political consultant who worked on his runs for City Hall, and Ray Harding, the Liberal Party boss whose support was crucial to Giuliani’s victorious 1993 campaign. This tight orbit of New York advisers is one of the things that keeps Giuliani at a remove from the national party, even though top operatives gush about Giuliani’s allegiance to the cause. “His relations with the national party are good right now,” says a Republican political consultant. “He’s being helpful, and everybody appreciates it when they’re being helped.”

And even on social issues, Giuliani is seen as someone who can be educated. “I won’t be shocked if he decides that late-term abortion isn’t such a good idea,” says Siegel, who’s writing a book titled Prince of the City: Giuliani’s New York and the Genius of American Life. “It was never clear to me how much his abortion position was a matter of conviction and how much it was a matter of necessity. I suspect he’ll do a certain amount of repositioning; candidates always do that.”

“He’s basically very pragmatic,” Mario Cuomo says. “And he’s progressive. He’s not a Neanderthal, a primitive conservative. But look, he’s a clever human being. He can shave and draw fine distinctions if he needs to.”

Whether any of that matters in 2008 depends on whether the country is still mired in a shooting war in the Middle East and in fear of terrorism at home. Curiously, anxiety over another terrorist attack is more palpable in such unlikely targets as Macon and West Palm Beach than it is in once-and-future target New York. When Giuliani, who has made himself the physical and symbolic embodiment of September 11, comes to town, he both stokes the worries and holds out the promise of a salve. “I love his strength,” says Charlotte Harber, an actress attending a Giuliani appearance in Miami. “The politician who is willing to get his hands dirty—that’s who you want to vote for. He’s a real person. I definitely could see him as a presidential candidate.”

Giuliani, of course, is acutely aware he possesses something rare right now, a connection beyond politics, and he’s eager to nurture his new, softer image. “A lot more people got to know me after September 11, and they feel like they have a personal relationship with me,” he says. “And I think they realize I care about them.”

Message: I care. That sounds awfully presidential.

“Roo-Dee! Roo-Dee!”

Tonight the familiar chant comes with a Cuban inflection. Giuliani takes the stage in a swank Miami hotel ballroom, once again in service of the Mel Martinez for Senate campaign. Earlier, he’d spent an hour behind a black-velvet scrim, as a slow-moving line of more than 100 people approached to pose for pictures with America’s mayor. To one side of the room, however, sits a cluster of heavyset, solemn guys in their mid-sixties, speaking in Spanish; they’ve paid big money to get into the exclusive pre-speech reception and so are entitled to be photographed with Rudy, but they keep waving off invitations to stand in front of the camera.

When Giuliani moves from the flashbulbs to the main stage for his speech, the dim lighting sets off his sharply lined mouth and sharp incisors, making his face look like a woodcut. He seems tired, this being his third speech of the day, and gives a meandering performance, serving up the required digs at Fidel Castro and warmed-over praise of industrious Cuban-Americans. “You know the promise for Cuba is unlimited,” he says. “You can see the quality of the Cuban people when they’re given a chance. So now, if you give the entire island a chance, can you imagine what they’ll achieve?” The crowd begins to murmur, bored, as Giuliani riffs on the Yankees and El Duque, but erupts in chants and applause when he finishes.

Afterward, Rudy doesn’t mingle or work the room, not here or anywhere. He shakes a few hands, and then he disappears behind yet another curtain, leaving Martinez to chat up the stragglers. Six days later, he flies to Tempe, Arizona, for the third presidential debate. The crowd here is bigger and more surreal, a swirling carnival of media-politico-celebs: Greta Van Susteren passes John McCain, who passes Jesse Jackson, who passes Judy Woodruff squatting in a corner to do her own makeup. Failed candidates and handlers from both sides circulate through the media tent before the debate, pumping out quotes for the hundreds of idle reporters.

Rudy, though, stays sequestered. He’s flown to Arizona by private plane after serving up inspirational nuggets—by satellite from New York, to people paying $300 each—to the “10th Annual Worldwide Luminary Series,” alongside such self-help hucksters as Suze Orman and the Seven Habits of Highly Effective People guy. Instead, after the debate, Giuliani’s bodyguards whisk him through crowds, ignoring shouting reporters, past the jealous gaze of pols like Henry Cisneros. Giuliani goes directly from the front row of the debate audience to a seat beside Tim Russert and Tom Brokaw in the NBC booth overlooking the theater and serves up the red-meat Bush party line. There’s grins all around once the cameras are off and the earpieces removed. “Say hello to Judith for me,” Brokaw says, slapping Giuliani firmly on the back.

Rudy moves quickly to CBS, then CNN, Fox, MSNBC, and finally back to Fox for the Hannity & Colmes show, where his rhetoric is distinctly sharper. The most interesting thing about this interview, though, is that it’s the only one that Giuliani does in the main media tent. Volunteers prowl toting enormous placards bearing the names of various spinners—RICHARDSON, HUGHES, CLARK, ROVE—as enticements to the media mob. Giuliani doesn’t want to be lumped in with the mere shills, so when one of his press aides spots a giant Bush placard with GIULIANI affixed to the bottom, he demands that Rudy’s name be stripped off.

Despite all the airtime, the Democrats don’t believe Giuliani is doing Bush much good. “They trot him out for his 9/11 credentials, but on most of the other issues that define Bush’s agenda, he’s at odds with the president,” says Joe Lockhart, a Kerry adviser. “And he hasn’t been effective in helping the president make his anti-terrorism case. The president’s numbers on Iraq and terror continue to dwindle.”

“There can be Rudy the hero and Rudy the hack,” says Kerry aide David Wade. “And lately he’s chosen to be Rudy the hack. I don’t see a big future for him.”

The Republicans claim that Giuliani is one of Bush’s most powerful surrogates, especially on terrorism. Yet the Bush campaign hasn’t asked him to cut any TV commercials. And with the extremely close race coming down to its final days, Giuliani chose to spend most of last week in England, Germany, and Italy, giving speeches (and missing the Red Sox beating his beloved Yankees). “A business trip that was scheduled a long time ago,” Sunny Mindel says. He’s expected to be back in the swing states this week.

In Tempe, after he finishes with Hannity & Colmes, Giuliani steps back into the cocoon of his bodyguards; when a well-wisher tries to pat Giuliani on the back, one of the security men peels the college kid’s hand back like a banana skin. Rudy makes a quick cell-phone call to his wife, all the while striding through the dark parking lot. He’s skipping the parties and the giant Bush rally at a nearby baseball stadium, where McCain and the other top Republicans are leading the cheers. Instead he’s flying all night to Pennsylvania, to attend an Arlen Specter fund-raiser in the morning. He climbs into the backseat of a waiting SUV and stares out the window. No matter how much Rudy Giuliani may be ingratiating himself with George Bush and the national Republican Party, and no matter how much he turns his back on his hometown in the process, he’ll always be something of a lone wolf. And in that way, at least, he’ll always be a New Yorker.