In the summer of 1995, on a listless, steamy July evening, I interviewed Mayor Rudolph Giuliani about New York’s falling crime rate. We met at Huxley’s coffee shop in Rockefeller Center, right after he taped a talk show at NBC. As we sat sipping iced tea in a peach-colored vinyl booth in the nearly deserted restaurant, the mayor talked about his vision for New York; he wanted to return the city to the way it was in the thirties and forties, when neighborhoods were safe and New York was, truly, a 24-hour town.

Though he’d been in office only eighteen months, Giuliani was well on his way to that goal: On his watch, murder was already down 37 percent, and overall, serious crime was down 27 percent. The decline had been so steep and so fast, after years of what seemed like uncontrollable mayhem and disorder, that it was difficult for many people to accept, indeed to believe, that a real change was taking place.

In a year and a half, Mayor Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton had done what the city had long been screaming for somebody to do: They had taken back the streets. Using good, basic management and smart law-enforcement techniques, they had overturned three decades of received wisdom about how to fight crime in America.

While the mayor took a call on his cell phone amid the clanging of dishes from the restaurant’s kitchen, I couldn’t help thinking about the breathtaking possibilities for the city. If the mayor had been able to turn around an organization with a culture as entrenched as the Police Department’s, a department that had never before in its history been successful at actually reducing crime, then what would happen when he began to focus on the schools? Or the child-welfare system? And in a city where people felt safe, wouldn’t the always-festering racial tensions begin to ease?

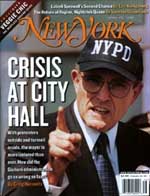

But now, almost four years later, as the mayor heads toward the halfway point of his second term, little of that promise has been realized. Instead of capitalizing on his early success, Giuliani has wasted his momentum on a continuing series of avoidable squabbles that accomplish little beyond securing his reputation for meanness. Feuding with Governor Pataki; vanquishing the portraits of former mayors Koch and Dinkins from City Hall’s Blue Room; beating up on Councilman Steve DiBrienza, who dared to disagree with him on homeless shelters, by trying to close a popular, thriving social-service center in his district; building himself a $15 million emergency-command-and-control bunker in the World Trade Center; using security concerns to cut off much of the public access to City Hall. The battles, the imperial decrees, and the public-relations blunders have seemed for some time now to be all about power, not policy. It’s the exercise of muscle without ideas.

“I tell him all the time,” says one of his closest confidants, “that he doesn’t have to come out every day and prove he has the biggest dick in the city. Everybody knows it. But Rudy is who he is.”

Since winning re-election in 1997 (a night when he promised to reach out to all New Yorkers, even those who didn’t vote for him), Giuliani has looked like a man without an agenda, other than his ambition for higher office. Even key aides, when asked for specific policy initiatives being pursued, come up with little more than bromides about continuing the quality-of-life campaign. As he lurches from one ugly skirmish to another – cabbies, street vendors, pedestrians – he seems to have grown little in his five and a half years in office.

Increasingly isolated, prickly, embattled, and convinced the press is out to get him (a Richard Nixon comparison is irresistible), the mayor has demonstrated little ability to broaden his range. And so by the time four cops fired 41 shots at Amadou Diallo on Wheeler Avenue in the Bronx, it came as little surprise not only that the mayor bungled his handling of the tragedy but that he had no one to cover his back when the storm of criticism broke.

Outmaneuvered by the Reverend Al Sharpton and a broad-based coalition of opponents, the mayor was laid bare, hopelessly vulnerable as a result of his arrogance. No black leaders to turn to for help. (They’d all been repeatedly spurned.) No expressions of support from former mayors. (They’d all been mercilessly belittled.) No vote of confidence from onetime crime-fighting partner William Bratton. (He’d been publicly humiliated and forced to resign.) No kind words from the governor. (He’d been embarrassed too many times.)

Clearly, the chickens have hungrily, gleefully, and relentlessly come home to roost. In the four years since I sat with him at Huxley’s, he has managed, with the help of his police commissioner, Howard Safir, and his communications director, Cristyne Lategano, his closest adviser, to turn one of the truly astounding achievements of modern government – more than 100 fewer people a month get killed in New York now – into a public-relations nightmare. Even worse, he has opened the door for a reversal of some of the very policies that have made the city so much safer.

Though the mayor professes publicly not to care about poll numbers, it must eat away at him that his approval ratings are, according to a Quinnipiac College poll released last week, down to an all-time low of 40 percent. (Only 23 percent of those polled approved of his handling of the Diallo shooting.) While his aides can dismiss this as a temporary, post-Diallo slide, in truth, his numbers were already heading south before the shooting.

To really appreciate how the mayor has blown it, you need to think back to 1993. It’s easy to forget that in the early nineties, the quality of life in the city had deteriorated so badly and solutions seemed so elusive that people inside and outside government – including revered urban gurus like Harvard’s Nathan Glazer and devoted civic leaders like Felix Rohatyn – were actually buying into the idea that perhaps New York was simply ungovernable.

It was a time of severely lowered expectations. If I had told you then that the city would elect a mayor who, over five and a half years, would reduce the murder rate by 70 percent, you would have thought I was crazy. But you’d probably have agreed that any politician who could do that would be the most popular mayor in this century, if not of all time. Mayor Giuliani, however, is hardly being hailed as a hero (except, perhaps, among Republicans outside New York City). In fact, he’s lucky he doesn’t have to run for re-election.

“It took people eleven years to get tired of Koch but only a little more than five to tire of Giuliani,” says Democratic political consultant Hank Sheinkopf. “Winston Churchill was a great man, but when the war was over, they got rid of him. Well, the war is over, and if there were a way to get rid of Rudy, they’d get rid of him today.”

Though the Diallo tragedy is the first full-fledged crisis of the Giuliani mayoralty, it has exposed a range of issues that have been bubbling near the surface for some time. And only some of them relate to the Police Department’s behavior in minority communities.

With no articulated, substantive second-term goals (remember the civility speech?), this administration has seen its progress come to a screeching halt. Whether distracted by the mayor’s next career move or hampered by the loss of key people from his first term, the Giuliani government seems devoid of ideas. And while the administration grinds along in woefully low gear as a creative enterprise, there have been recent signs of internal dissension as well. Rudy Crew, with whom Giuliani had enjoyed a solid working relationship, threatened to resign over the mayor’s sudden urge to promote school vouchers. And according to City Hall sources, several longtime members of the mayor’s inner circle have recently gone to him to complain about the obstructionist, bellicose role played by communications director Cristyne Lategano. They have tried to convince the mayor that if he plans to run for higher office, he must, at the very least, redefine Lategano’s position.

“When you come right down to it, the fallacy of Giuliani’s second term,” says a former member of the administration, “is that he’s still riding the one singular success he’s had in office – crime reduction. He’s got this reputation as a great manager, but what else has gotten managed better? Reading scores are no better than they were under Dinkins, children’s services are no better, either, and they threw people off welfare without creating jobs and then claimed they reformed the welfare system. So of the areas the mayor has always claimed he wanted to focus on – crime, education, kids, and welfare – what besides the Police Department has been managed better?”

And with his mishandling of the Diallo shooting and its aftermath, the mayor has managed to turn his most visible asset into his most visible liability.

“The Diallo shooting was a terrible tragedy, an incident that clearly called for some healing,” says a former member of the administration. “And the mayor did publicly express his sympathy to the family. He also said it was a time to reserve judgment until all the facts were known. But then, of course, while the smoke is still coming out of the holes in Mr. Diallo’s head, he pulls out his charts and his Police Department statistics and says, in the meantime, I’m right.”

“With Rudy, everything comes down to who’s right and who’s wrong,” says another insider. “And this always translates, of course, into I’m right and you’re wrong.”

The current crisis at City Hall can be traced to Howard Safir’s decision in January 1997, against the explicit advice of experienced commanders, to triple the size of the Street Crime Unit. The expansion was based on the elite unit’s success: If 138 cops were producing remarkable results, imagine what 380 could do. So, in an effort to continue driving the crime stats down, Safir put 242 untrained, inexperienced, and poorly supervised guys into plainclothes and gave them one week of plainclothes training and one day of video about confronting people in cars and on the streets. Then he stuck them all together instead of pairing them with more experienced partners, because the math simply didn’t work. When you add 242 to a unit of 138, there aren’t enough veterans to go around. (The four cops involved in the Diallo shooting all joined the unit in this expansion.)

“Then they quadrupled the number of people they stopped and frisked on the street; that they admit to,” says a one-time administration insider. “Because, as anyone who’s ever worked the street knows, cops don’t bother to fill out 250s on most stops. And they confiscated the same number of weapons as when they were stopping one quarter as many people. It’s just been a fucking disaster.”

Though Giuliani’s refusal to rush to judgment on the actions of the four cops indicted for shooting Amadou Diallo was certainly to be expected, the cold arrogance on view was mind-boggling. Giuliani talks about one city, one standard, yet until the Diallo shooting, he refused even to meet with Manhattan borough president Virginia Fields or state comptroller Carl McCall, the highest elected black officials in New York.

And Commissioner Safir’s announcement, within nine days of the shooting, that New York City police officers would be given hollow-point bullets displayed a disregard for people’s feelings and a case of political tone-deafness that left even some of Giuliani’s staunchest supporters dumbfounded. Even if hollow-point bullets make sense, and even if the announcement had been previously scheduled, didn’t anyone think it might be a good idea to postpone it?

It took a personal revelation two weeks ago by deputy mayor Rudy Washington (the only high-ranking black in the administration) that he has been stopped and hassled by the police because he’s a black man for the mayor to even come close to publicly admitting that this is a widespread problem. (Perhaps not surprisingly, Washington is viewed among black leaders as a nice man who, as one of them says, “has no ties to black leadership and absolutely no credibility in the community because no one believes he has any real influence with the mayor.”)

And now, in a search for quick fixes, the mayor and the police commissioner have put the Street Crime Unit back into uniform, a change that will, according to police experts, severely limit its ability to do the very thing that made it so successful – get guns off the streets. And in a separate move that seems lifted from a Stanley Kubrick satire, the cops have been issued wallet-size instructional cards on courtesy, reminding them, among other things, that a man is called Mr. and a woman Ms.

By choosing hubris over contrition and unconvincing gestures over real changes, the mayor has actually betrayed the police department he claims to be championing. He let perception become reality. Lost in all of the post-Diallo rhetoric and frenzy is the fact that New York’s Police Department has more contact with more people resulting in fewer violent encounters than almost any other department in the country. The mayor tried to make this point, but the debate was dominated by his intransigent, insensitive attitude and the widely held belief that he doesn’t care about the concerns or the fears of the city’s blacks and Latinos. Why should they believe otherwise?

“Clearly he played it wrong,” says the Reverend Al Sharpton, who for the first time has been able to put together a protest coalition that extends beyond his natural base and crosses racial, political, religious, and economic boundaries. “Instead of being conciliatory, he came off like a southern mayor, and that made it much easier to mobilize. I think Giuliani thought all he’d have to do is wait me out. I’d have a rally or two, and that would be it.”

This misread of the situation appears to have been based on at least two false assumptions. First, as Sharpton says, the mayor undoubtedly believed that the anger and disappointment fueling the demonstrations would quickly dissipate. He had a precedent to go on here. When Abner Louima was brutalized, Sharpton led thousands of marchers across the Brooklyn Bridge. But the mayor was able to quell the protests quickly, largely by appointing a task force to recommend changes in the Police Department (months later, after he was re-elected, he openly ridiculed its recommendations).

His second faulty assumption, I’m told by people familiar with the situation, is that he believed he had the cooperation of the Diallo family, meaning that they would not reach out to Al Sharpton for succor and advice. Nor would they actively participate in any protest movements. The mayor believed this because immediately after the shooting took place, he talked to Saikou Diallo, Amadou’s father, on the phone. And Diallo’s father was moved by the mayor’s call. However, sources say, Saikou didn’t realize, even after talking to the mayor, that his son was shot by police officers.

But by the time the family landed here – the father lives in Vietnam and the mother in Guinea – it was clear that the mother was in charge, and she had a very different view of things. In any event, Giuliani spent the first week after the shooting going on the incorrect assumption that he had the family. Once he learned he didn’t, he had to scramble. He even went to their hotel, where he waited 45 minutes but never got to see them.

All in all, by the time the Diallo funeral in Africa was over, the mayor was several weeks into the crisis without a strategy. And while Sharpton was skillfully orchestrating the civil disobedience in front of One Police Plaza – parsing out the celebrity protesters on different days to maintain media coverage – Giuliani and his people stayed true to character, dismissing the demonstrations as “silly” and politically motivated. And in what seemed to be a not-so-veiled reference to race and class, the mayor made the astonishing remark that the demonstrations were peopled by the “worst elements of society.”

“I told the mayor,” says one of the few community leaders to have a decent relationship with Giuliani, “that the anger in the black community is legitimate and widespread, and it’s cutting across economic lines. It had already been there, but the Diallo shooting crystallized it. I told him it is serious and he needs to understand this. He assured me he did.”

Publicly, however, the mayor and his supporters seemed intent on delegitimizing the voices raised in protest in whatever way they could. With an eye on the Senate race, the mayor and his allies zeroed in on politics rather than on the problem at hand.

“You think that these arrests that go on day after day are just because a terrible thing happened?” says consultant David Garth, architect of the mayor’s first successful run. “I think it’s very well organized, very smart, and very well choreographed. And there’s no way you’re going to convince me that Harold Ickes isn’t involved here. All of a sudden, the president talks about police brutality in his Saturday radio address? These things don’t happen by accident – not when Hillary Clinton is thinking about the Senate race.”

Liberal Party boss Ray Harding, a longtime Giuliani confidant, offers a similar take. “This is a political operation against Rudy, and the core group is made up of the usual cast of characters,” he says.

Sharpton dismisses the charge that anyone’s using a family’s misfortune to play politics as, at the very least, hypocritical. “Who used a tragedy more politically than they did with the Rosenbaum family after Crown Heights? The Rosenbaums campaigned for both Giuliani and D’Amato. Dinkins was called a murderer. I’m not calling anybody any names. And nobody’s running for anything now,” he bellows.

“Imagine if Dave Dinkins had handled that situation the way Rudy’s handled this one. Imagine if he said, ‘I’m not going to Crown Heights to meet with the Hasidic leaders; I’ll meet with Manhattan borough president Ruth Messinger. She’s Jewish, too; that’s good enough.’ Well, that’s what Giuliani just did. If Dinkins had done that, he would’ve been run out of town.”

Sharpton may have a point. But the mayor’s recent meetings with black elected officials, no matter how overdue and no matter how desperate they seem, are at least a small step in the right direction. The difficulty for Giuliani is that they do little if anything to improve his immediate situation.

“No one takes those meetings seriously,” Sharpton says, overstating the case a bit. “Because those aren’t the people directing the movement. So fine, he meets with those people, and you still got 200 people a day going to jail. So what did he do? Police brutality will be the top news story all summer, with the Louima trial and the Diallo indictments. This is not going away.”

Part of the mayor’s problem as he tries to deal with the difficulties of his second term is that he has never been a man in search of advice. He is interested only in reflected light. He doesn’t want to be told that he’s wrong, that he should do something another way, or that he should consider a different approach. “No one within the administration,” says a recently departed staff member, “has ever been able to say no to the mayor – ‘You cannot do that.’ “

This situation has become more critical as he moves through his final two and a half years in office with an inner circle that’s always been quite small thinned out even further by departures. Though it’s a normal part of the political cycle to lose staff at the start of a second term, the mayor has lost some of his closest aides, people he has known the longest and trusted the most: Peter Powers, Randy Mastro, Richard Schwartz, John Dyson, Fran Reiter. (Although most of them continue to speak to the mayor regularly.)

Several people who have been in negotiations with members of the mayor’s staff recently have noticed a difference from the first term. “The newer people don’t seem to know their principal as well as the original group did,” says one. “And that can make things difficult.” Another told me they never come to the table with the ability to negotiate. They always have to go back to him before they can make a move.

The City Hall brain drain is particularly important where Giuliani is concerned because he is naturally suspicious and trusts so few people. His administration has always been marked by a kind of siege mentality, an edgy belief that because it’s trying to change the city, its enemies are everywhere – the press, the Democrats, the unions, the race baiters, the Board of Ed. And so, in his search for people he can trust – he values loyalty above everything else – he has, over time, relied more and more on Cristyne Lategano.

She is the continuum, the one constant through more than five years in office and two campaigns. Criticized for her handling of the media, ridiculed for her lack of credentials, accused of being the mayor’s lover, and implicated in nearly every public-relations disaster the administration has suffered, she has not only survived but become his closest aide, his confidante, and his constant companion. He picks her up in the morning, he drops her off in the evening, and in between they are together eighteen hours a day. Several nights a week, they can be found at Cooper’s Classic Cigar Bar, on 58th Street, having dinner, relaxing, and discussing policy.

“She permeates every aspect of city government,” says a City Hall insider. “And there isn’t a commissioner or a senior member of the administration who’s not fearful of her. The mayor believes she can walk on water.”

Though she has even been dubbed “co-mayor” by a couple of people on his staff, that really misses the point. She is more like a cheerleader or an agitator. Picture her as the corner man at a boxing match, splashing water on her fighter’s face, emphasizing the opponent’s weaknesses, telling him which punches to throw, and urging him on with a constant You the man kind of chatter.

It is again a measure of his arrogance (and hers) that even after several embarrassing waves of publicity regarding their relationship, nothing much changed. “What we at City Hall really resented was their complete disregard for the perception created by their behavior,” says a former staff member.

“Despite the widespread rumors, however unfounded we chose to believe they were, the mayor and Cristyne altered none of the actions that led to those rumors. A more seasoned political-communications person would certainly have understood that steps were necessary to address them, even if not directly. There was a complete disregard for appearances.”

There’s no question, however, that it’s been a difficult road for the two of them. Almost immediately after his election in 1993, she provoked severe hostility from the reporters who cover City Hall with her often dismissive attitude and her willingness to cut off anyone who wrote something negative about the mayor.

And it is a revealing detail about Giuliani’s personality that the more she was attacked, the more he dug in his heels. “He viewed those attacks on her as attacks on him,” says a recently departed staff member.

“She was the key representative of the mayor’s combative style,” says another former member of the administration. “And she was the emblem of an administration where people in critical jobs had little or no experience in those jobs and were simply carrying out the mayor’s imperatives.”

Just when things seemed to reach critical mass in 1995, Lategano was lifted out of harm’s way through a promotion from press secretary to communications director. With her new title, she got a raise, an office adjoining the mayor’s, and a reprieve from having to mix it up every day with the reporters. “Her new title – communications director – was the perfect oxymoron, since she neither communicated nor directed,” says one former insider.

“So here you have a mayor who has a tin ear for public relations, a tin ear for politics, and a bad mouth. And his key adviser has no ear for public relations and no ear for politics because she’s had so little experience at both. She tells him all his ideas sound great and then passes them on to underlings as policy that’s supposedly been vetted by the mayor and his key communications analyst.”

Their relationship matters because she is on the public payroll at a salary of $140,000 a year and because of the impact she’s had on his mayoralty and the affairs of the city. She controls who gets to see the mayor and when. She is the aide who has his ear after meetings. And according to insiders, she is the person who reinforces his worst instincts, never urging him or pushing him to avoid a fight or to take the high road.

It is telling that even before the Diallo shooting, in the face of the social and economic miracle the mayor is so fond of proclaiming he has engineered, his job approval numbers were not better. Though they peaked at over 70 percent early in 1998, by last summer they’d fallen to 55 percent. And despite his accomplishments, his personal approval ratings have never matched his job-performance numbers.

Would this be different with someone else sculpting his image? Would he have gotten more credit for the drop in crime if there’d been a better communications strategy? Would he have been able to avoid always looking like the bad guy in every fight – even when he’s right – if someone else had been running his press operation? Would he have reached out more often or built more constructively on his early success with better advice?

It’s hard to say. But history shows that whoever has tried to convince the mayor he’d be better off without her – including lifelong friend Peter Powers – has ultimately been pushed away. By outworking her enemies and attaching herself to the mayor’s side so that there’s never an opportunity to badmouth her, she has vanquished her opponents.

“This has increased her influence enormously,” says someone who knows her well, “because she no longer has to defend herself and fight those daily battles. None of the people who have joined the administration more recently would even think of taking her on.” It’s been left to those who’ve known the mayor longer.

The lack of a coherent communications strategy has frequently turned even victory into a P.R. problem. For example, something as innocuous and as positive as naming a highway for Joe DiMaggio became simply one more ugly political episode – after the mayor had already gotten his way.

Giuliani wanted to name the West Side Highway after the Yankee legend, while the governor, though uncommitted, had mentioned the Major Deegan. When DiMaggio died, Giuliani and Pataki spoke on the phone, and Pataki, informed that the ballplayer’s family preferred the West Side Highway, told the mayor it was okay with him.

“The governor told the mayor,” according to someone on Pataki’s staff, “that he would talk to the legislature and move the bill forward. So the mayor had won without a drop of blood being shed.”

But the next day, the mayor’s office released a letter from DiMaggio’s lawyer that said a number of unflattering things about the governor. “Clearly, releasing that letter was simply an attempt to embarrass the governor,” says the Pataki staff member. “Giuliani had already won.”

And so, even though the mayor was going to get what he wanted, he also got a week’s worth of bad press about his petty, ego-driven war with the governor. The skirmish had Lategano’s fingerprints all over it. “Cristyne told the mayor,” according to someone familiar with the circumstances, “that he should release the letter. So the mayor got what he wanted, but thanks to her, not without some damage.”

There was even speculation – denied by DiMaggio’s lawyer – that the mayor’s people (read: Lategano) had gotten the lawyer to write the letter in the first place.

The problem Giuliani has now is how to juggle his career plans (he’s New York’s first term-limited mayor) while facing issues (the Louima trial and the Diallo aftermath) that have the potential to divide the city. Any further missteps could have an impact on his political future.

“It’s not that anybody wants him to fail in governing,” says political consultant Hank Sheinkopf. “Because if he fails in governing, we all fail. But you can’t ignore the fact that he refuses to listen to anyone or to take counsel. And the fact that Cristyne and all the other acolytes are there around him is an indication of that. She’s not the problem; she’s emblematic of the problem. He’s the problem.”

But in Giuliani’s reach for higher office, she could become a problem. In a Senate campaign that attracts national attention, questions about their relationship – which has been covered only intermittently by City Hall reporters – would most likely increase in frequency and intensity.

So could the mostly hands-off policy regarding Giuliani’s obviously strained marriage. Donna Hanover is the first lady of New York in name only. She bristles when she is referred to by her married name, she rarely appears with the mayor in public, she played no role in his last campaign, and she steadfastly refuses to even say whether she voted for him.

At her 25-year college reunion (Stanford), the organizers reproduced each student’s yearbook picture and the little description that ran underneath it. And they also added an update. Hanover’s little bio listed her name as Donna Hanover, and her address as Gracie Mansion. It said that after graduating, she went into journalism, working in various places, including Miami.

It went on to say she moved to New York, worked for Channel 11 and the Food Network, and then “I became first lady of New York.” There’s no mention of getting married, no mention of Rudolph Giuliani, and no mention of the mayor of the city of New York. This is how she sums up her life.

“It is perhaps the only good by-product of the mayor’s horrible relationship with the press,” says a former insider, “that the reporters know not to bring these subjects up. They know if they do, they won’t get answers and they’ll be publicly insulted for even asking the questions. But if the questions were asked more regularly, say, as they might be in a campaign for higher office, the mayor would be forced to spin more and to actually come up with some answers.”

For Giuliani’s supporters, and for people who, like me, believed there was so much early promise, the question that needs to be answered now is, what kind of character does he have? Is he capable of showing humility when events so clearly call for it?

Can he put aside this bizarre notion that he’d be “kowtowing” if he backs off just a little and extends himself to the city’s minority communities? Can he make some meaningful changes in the Police Department to take that success to the next level? And can he spend whatever time he has left in office tackling something worthwhile?

“Police brutality is an important issue,” says New York Urban League president Dennis Walcott, “but it’s important to remember that the city’s education system is killing a lot more children than the police. Education should be the No. 1 issue in the city now. And what the mayor can do is develop a master plan for public education and talk about how we as a city can come together around this issue.”

But how long he can keep his attention focused on the city may depend on what kinds of plans he has for the future. A run for the Senate will begin to require more and more of his time and energy by the end of the year – particularly if it’s a competitive battle with Hillary Clinton.

There are still people, however, who doubt that he’ll even make a Senate run. “I know for a fact,” says a key member of Pataki’s staff, “that he’s had a number of conversations with people saying he wants to be governor.”

His staff is fond of saying he’s not a politician, and the mayor himself often says he isn’t interested in changing to make himself more popular. “He’s not some poll-obsessed Bill Clinton,” one of his chief aides says, “ready to go whichever way he thinks public opinion is blowing.”

Though an argument can be made that everyone’s sick to death of politicians who spend more time spinning than working on the people’s business, the mayor’s failure to recognize the importance of positioning himself – and of good public relations generally – has cost him dearly. Remember, he came to power as a reformer, an activist who pledged to shake up and dismantle the lethargic, apathetic (read: liberal and Democratic) Establishment that he believed was responsible for the city’s sorry condition.

But to be a reformer means you have to bring the public along. You have to move public opinion. To gain support for radical ideas, you have to explain them, sell them, even romance the public with them. Whether it’s a baseball stadium on the West Side, pedestrian barricades at the crosswalks, or school vouchers. In other words, you have to be a leader.

Being a leader is more complex than having the guts to risk your popularity by standing up for something you truly believe in. Clearly, Giuliani has to learn there are times when the city needs someone who can reach out, build bridges, and bring people together. Now, for the first time, his future may depend on it.