Even now, they are outsiders in an outsiders’ world.

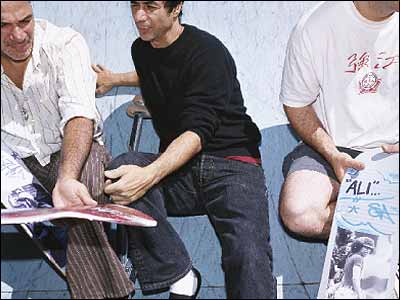

On an exquisite late-spring afternoon, Andy Kessler is leaning against the promenade wall overlooking the Riverside Park skate park, at 108th Street, when a skateboarder approaches and asks him when the park will open. Kessler, who has skated the city streets for most of his 44 years and has the raw-boned build and craggy, could’ve-been-a-Ramones-roadie look to prove it, doesn’t know. The two strike up a conversation, and at one point, the term “Zoo York” comes up. Of course he’s heard of it, the kid says, rattling off the names of riders associated with the skateboard-and-clothing company owned by Ecko Unlimited.

Kessler says nothing, but after the younger skater departs, a pained frown washes over his face. “That’s a prime example,” he says, his voice a sharp rasp. “Prime. He has no clue. No clue whatsoever.”

Kessler has grown accustomed to these reactions. Thanks to the 2001 documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys and now Lords of Dogtown, a new feature film based on it, everyone seems to know about the California latchkey kids who revolutionized skateboarding in the seventies. But what few realize is that during the same period, New York had its own Dogtown: a loose-knit collective of skateboarders and graffiti artists known as the Soul Artists of Zoo York, with Kessler its most prominent rider. This Zoo York—not the Ecko brand—attacked embankments and plazas with the same body-be-damned abandon as its peers on the West Coast. This Zoo York had members with Warriors-style names like Puppethead, PaPo, and Haze. (In fact, the two worlds converged when the movie was filming in 1978 in Riverside Park—the Zoo crew’s Upper West Side turf—and extras dressed as gang members gathered to watch the teenage skaters.) This Zoo York pioneered the art of city skating, and did so in an environment that iconic Dogtown rider Tony Alva calls “fucking gnarly. We live in paradise compared to those guys.” The Zoo York riders, whom Alva met and rode with in the seventies, “were one step behind us,” he recalls, “right on our heels, doing verticals as high as you can go, getting as aggressive as you can get. They were super hard-core.”

They skated for the same reasons everyone else did, and still does. “We wanted to get away from our parents and feel free,” recalls another Zoo rider, Jaime Affoumado, 39, “and skateboarding is the ultimate freedom.” Yet while everyone remembers celebrated graffiti writers like Zephyr and Futura 2000, the skating contingent of the Soul Artists of Zoo York has been almost completely forgotten and undocumented. Even the city administrator who oversaw Riverside Park has no memory of seeing them there.

“We had skateboarders here who ripped,” Kessler says, strolling—make that hobbling—through his crew’s old turf. Skating an indoor bowl downtown a few weeks earlier, he fell so hard that he broke his left kneecap and pelvis, requiring crutches. “People didn’t even realize skateboarding was going on here. We were all doing the same shit. The guys out in California were just more fortunate.” Kessler and his peers have to settle for a distinction all their own: a starring role in one of the city’s great lost stories.

Everyone remembers the wood planks, especially Catalino Capiello Jr., known on the then-dodgy Upper West Side streets of the late seventies as PaPo. One day in 1978, the genial half-Italian, half–Puerto Rican teenager was roaming his ’hood, skateboard in hand. At Riverside Drive and 95th Street, he came upon a construction site at the off-ramp of the West Side Highway. But something was missing—namely, large chunks of the plywood barricades. Peering inside, PaPo saw them for the first time: grubby kids like himself. Skateboarding. In the park. On a ramp.

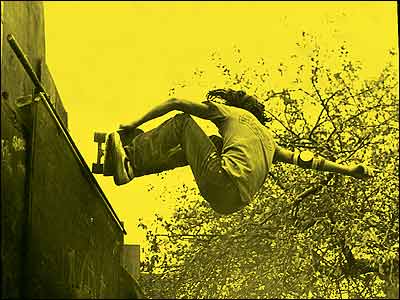

“I thought it was phenomenal,” Capiello, now 41, recalls of the first time he saw the Zoo York skaters. “I’d never seen anything like that.”Actually, “ramp” was too kind a term for what Kessler, who was skating that day, calls “rickety pieces of shit.” They were the most basic of eight-by-four planks, usually purloined from unattended construction sites on weekends. (One night, the skaters found a good stash at a site outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, then had to haul the wood across Central Park and into Riverside.) First at the 95th Street off-ramp and later at 116th and Riverside, the skaters shoved the wood up against whatever structure could sustain it and battered it into place with bottles and rocks. Then they would toke up and, with the Hudson River providing as much of a scenic background as they were likely to find, push off on their boards and aim full speed at the concave wood: Up the ramp … almost to the top … back down. Try again!

“They were these sick, sick guys,” recalls Ricky Mujica, 43, a friend of Capiello’s who, like PaPo, would soon become a Zoo Yorker himself. “Fifty percent of the time they’d kill themselves. But every once in a while they’d make it, and there was a big cheer.” When the skaters returned the following day, chances were that the ramp had been torn down by cops, and the routine would repeat itself.

“The further uptown you went, the quieter and more desolate it was,” Kessler says. “And the more you could get away with.” During their heyday, the Soul Artists of Zoo York got away with a lot. The name actually referred to two different but overlapping groups. The Soul Artists were the graffiti crew, first established in 1972 by a soft-spoken 15-year-old artist named Marc Edmunds, who briefly attended Columbia University (he lasted one month as a 16-year-old freshman). Known as “Ali”—the name he tagged onto walls and trains—Edmunds, who was half–Native American and half–African-American and is still spoken of in hushed, reverential tones, is said to have conceived the term “Zoo York.” “He said the place was like a zoo, literally animals,” Kessler recalls, “but in good and bad ways.”\The skate scene began to coalesce around the same time. Since some of the skaters also tagged and some graffiti writers skated, it was inevitable that their worlds would converge, which they often did at the Central Park band shell and in Edmunds’s apartment on Columbus Avenue between 106th and 107th streets. With Edmunds’s approval, the skaters adopted the name Zoo York for themselves. Emulating what the Dogtown riders did with their logo, Soul Artist writers like Haze, Revolt, and Zephyr drew the words Zoo York in the shape of a cross onto the bottom of the skaters’ boards. They were ready.

Much like the Upper West Side of their childhood, the Zoo York skaters zigzagged across racial and economic lines. Affoumado was a Bronx-born child actor, while Mujica was living on 94th and Amsterdam with a mother who worked as a keypunch operator for IBM—he learned early on where to scrounge for free bread. Manhattan wasn’t known as a skate mecca—it still isn’t—but they didn’t care. All they yearned to do was transform their drooping city into a playground, and to do so with moves primitive by today’s standards: riding on the edge of one wheel on the ramp, grinding their axles on flower planters, or attempting a complete spin, or 360 (which gave Affoumado his nickname, Puppethead, for the way his head looked when he did one). They rode so hard that, according to Zephyr, a.k.a. Andy Witten, “their boards, after I painted them, would last about two hours and be scraped back down to the wood.”

The de facto leader was Kessler, a long-haired, long-nosed urban string bean born in Greece and raised on West 71st Street by a floral-shop-owner dad and gym-teacher mom. Everyone has their choice Kessler story, like the day he refused to move to the back of a crowded bus, telling the driver, “You move to the back. This place is a sardine can. I’ll drive the bus.”

The skaters aimed full speed at the concave wood. “They were these sick, sick guys,” recalls Ricky Mujica. “Fifty percent of the time they’d kill themselves.”

“The next thing we know,” recalls Mujica, “Andy is thrown out by the driver, and his skateboard comes flying out after him. People didn’t like skateboarders back then.” After chasing the bus for four blocks, Kessler smashed the window with his board. Then there was the time Kessler refused to don a helmet at a skate park in New Jersey and was chased by guards trying to force him to wear one. Fights were commonplace. “I was a good skateboarder,” Kessler admits, “but a real prick to most people.”

Eventually, the crew expanded to nearly fifteen strong—larger and more intimidating than skate gangs in the West Village, Riverdale, Brooklyn, and the Upper East Side. In 1979, Edmunds cemented their reputation and cult by publishing a one-off ’zine, Zoo York, that devoted its “Sports” page to a fictional championship match between the skaters and another crew. There were, in fact, never any competitions, but an outlaw legend was born. Although Kessler says they came from “decent families and went to decent schools,” they weren’t above playing the bully and preying on other kids. They even pinched decks from outsiders riding near the Alice in Wonderland statue in Central Park. “Throw their boards in the lake,” recalls Kessler, “and make them do laps until we fished their board out and we’d either give it back to them or divvy it up—somebody would get the wheels, somebody would get the trucks. Primitive carjacking.” The first time Affoumado skated with them, bringing along an expensive new deck, “they traded boards with me, and all of a sudden mine was gone.” Then 12, Puppethead cried all the way home. Mujica obtained one deck during the 1977 blackout, when he and friends helped loot a sporting-goods store. At another shop, Edmunds got his mom a new blender.

Of course, this was the seventies—which, as the saga of the Zoo York crew reminds you, was a comparatively lawless time in the city. In the rare moments when they were hassled by cops, skaters would usually roll away with a disorderly-conduct summons—not the fines for the ill-defined “reckless operation” of skateboards on New York City public streets that were signed into law in 1996. (A state law, implemented this January, makes it mandatory for riders under 14 to wear helmets, which the Zoo riders rarely did.) “I see what they did as a lost art,” says Steve Rodriguez, founder and owner of 5boro Skateboards. “Skating in a raw environment doesn’t exist anymore in New York City. You can’t make a ramp in Riverside Park. You can’t find empty pools. Everything’s so policed now.”

Even so, the city never made it easy for them. Manhattan had no skate parks, so the riders had to venture to, among others, a sketchy one in Jackson Heights—the surface of which was so craggy, they joked that the mob owned it and that the lumps were dead bodies mixed in with the concrete. In the winter, they’d shovel narrow paths to the ramps to ride in the snow.

In the pages of Skateboarder Magazine, they’d seen photos of their California heroes carving drained watering holes, and they yearned to do the same. So onto the 1 train to Riverdale they went, spraying graffiti on train cars along the way and scouring apartment complexes for the rare abandoned pool. One day, they stumbled upon an inground one in a building near Van Cortlandt Park. The walls were nine feet vertical and the cement so rough it felt like sandpaper on their pad-free limbs, but they loved it anyway. Dubbing it the “Death Bowl,” they dropped in and carved it almost every day in 1977, the super of the building hurling bricks and batteries at them from the roof of the building. “The fond memories are the ones where I’m pretty much running,” Capiello says. “We had no fear. We thought we could live forever.”

As with all mythical eras, theirs did not last long. The Dogtown riders became pros early on, formed their own companies, grew to be legends. By 1980, though, the Soul Artists of Zoo York were already disbanding. Several of the artists and skaters went off to college. While learning to ollie—jumping a skateboard without a ramp—Mujica injured his knee and switched to roller-skating, eventually touring with Starlight Express. One of Kessler’s best friends, JC, was killed by drug dealers in a buygone bad; another, Frankie Courtner, succumbed to AIDS. Edmunds developed a crack habit after unexpectedly switching over to a music career (his band, J. Walter Negro and the Loose Jointz, released a single on the short-lived Zoo York Recordz in 1981) and died in Arizona in 1994.

Kessler nearly fell victim to the same fate. By the early eighties, he was on what he calls “early crack patrol,” freebasing cocaine and experimenting with hard drugs. “I was on the cover of Thrasher in 1983 strung out on heroin,” he chuckles, recalling his five-year junk addiction in the mid-eighties. It took several busts—and his own parents’ taking out an order of protection to keep him away from them—to put Kessler on the bumpy road to recovery, after which he worked in everything from massage therapy to flea markets.

“Skating in a raw environment doesn’t exist anymore in New York City. You can’t make a ramp in Riverside Park. You can’t find empty pools.”

By then, the Zoo York crew, largely ignored by the West Coast extreme-sports media, had faded into what few history books would have them—until ex–pro skater Rodney Smith founded the Zoo York skateboard company in 1993. The appropriation of Ali’s hallowed name provokes mixed reactions in the original Zoo riders. Some live with it; others, including Kessler, grow livid when the topic is broached. “There’s no legitimacy to it,” barks Kessler. “Someone snatched up a name that meant something to people years ago. It has nothing to do with us whatsoever.”

“Some of these guys tried to stay away [when the company formed] because they weren’t for what we were doing,” Smith admits, while maintaining that, via an intermediary, he received Edmunds’s verbal blessing to use the name. “Anyone could have owned the name,” Smith says. “But I wasn’t coming at it like some random company using the name Zoo York and exploiting graffiti. Those were not my intentions at all. If they feel that way to this day, it’s kind of wrong.” Either way, Kessler is having none of it: “I wouldn’t be caught dead in a Zoo York cap.”

Look hard enough and you’ll still find the remaining Soul Artists of Zoo York ensconced in underground art or music. The graffiti writers continue to paint and spray, and have seen their art exhibited in galleries and featured on album covers. Of the skaters, Capiello now lives in San Diego, where he creates computer graphics for a publishing firm. Mujica is a painter in his old West Side neighborhood. Affoumado teaches kung fu and just opened Puppet’s Jazz Bar in Park Slope. Kessler designs skate parks; he’s done them in Riverside Park, Brooklyn, Hoboken, and at Pier 40 on the Hudson. Together, they’ve helped him patch together a living. For four years, he worked at the Riverside site. “The only frustrating thing is that even the graffiti writers got more acclaim than we did,” he says. “We didn’t get shit. Guys would think I was just some grumpy old guy sitting at the skate park.”

Near the now-quiet spot of an old West Side ramp, Kessler’s cell phone chimes. Calling from his home in Hawaii is, of all people, Jay Adams, the baddest, fiercest, and most busted of the Dogtown crew. A casual friend of many years, Adams heard Kessler had taken a serious spill and was calling to hear all about it.

“Yo, Jay-Boy!” Kessler roars, and, beaming, fills in Adams on his injury. Kessler has admired the Dogtown riders since first reading about them in skate magazines 30 years ago, and even skated with them in 1978 at the legendary Cherry Hill skate park in New Jersey. “To me, Jay Adams was the shit, and Alva too. I ended up skating a kidney”—a swimming pool—“with Jay for an hour, just me and him, and everyone sitting and watching. The session of a lifetime for me because Jay was the skater I admired the most. That’s the stuff we dreamed about as kids, looking in the magazines, and there I was, skateboarding with him.” When the call ends, a smile breaks out over Kessler’s face, and the bitterness he still feels over his crew’s lack of recognition vanishes, at least for a while.

“So fucking rad,” he says, stabbing the ground with his crutches and pushing off into the park once more.

David Browne is music critic of Entertainment Weekly and author of Amped: How Big Air, Big Dollars, and a New Generation Took Sports to the Extreme.