Near the Third Avenue–138th Street stop on the 6 train, the Bronx neighborhood known as Port Morris looks frozen in the seventies. Forlorn-looking public-housing towers face one-story delis and Hub Cap City across Lincoln Avenue, and other bleak towers block views of the midtown skyline. There’s a steady hum of traffic over the Harlem and East River bridges.

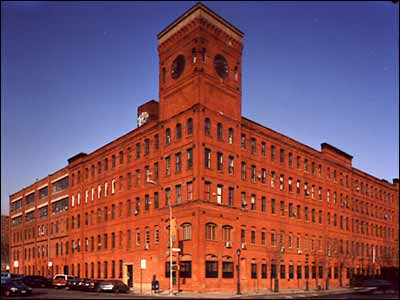

But walk a few blocks to the west, crossing under the Major Deegan Expressway, and you’ll see the first flickering signs of what Bronx officials have promised for decades. Young women in knit hats and pale fellows with delicately messy hair slouch by. A brick five-story building called the Clocktower (pictured) stands near the Third Avenue Bridge on-ramp, and there are satellite dishes bolted to a few of its windowsills, marking, like pins in a map, where residents have replaced factory workers. The Bruckner Bar and Grill, under the on-ramp to the highway, resembles a set for a mid-budget movie about Irish cops—cops who eat portobello sandwiches, that is. Is the South Bronx’s reinvention for real? Is Port Morris going from gritty to “gritty”?

Yes, but slowly. The Bloomberg administration and the Bronx borough president’s office are pruning the zoning rules here, to encourage a modest yuppie influx without bumping out the factories and small businesses that make their homes at this nexus of expressways. If they pull it off—and despite reports of tofu on sale at the Western Beef on Morris Avenue—boho in the Bronx isn’t going to take its usual home-wrecking, mesclun-strewn path.

Port Morris’s shift began in 1997, when a big local nonprofit called SOBRO spearheaded streetscape improvements—installing sidewalk benches and the like, planting trees—to coax antique dealers to Bruckner Boulevard. Around that time, the city rezoned five blocks near the water to allow residential as well as light-industrial use of vacant properties. Artists started moving into the lofts; a gallery, Longwood, now showcases local creatives.

Now they’re bracing for company. On March 9, the City Council voted to expand the mixed-use district another eleven blocks toward the river. “Our aim here,” says Purnima Kapur, the Department of City Planning’s Bronx director, “is to take an area that seems very well situated and increase its potential.” When I speak to Adolfo Carrión Jr., the thoughtful borough president, he admits to drawing inspiration, and early-adopting residents, from that other revitalized B-borough.

One of those early adopters, Melissa Calderón, is now a coordinator for the Bronx Council on the Arts. “A lot of people came from Williamsburg and Dumbo in the past year,” she says. A visual artist, Calderón took loft space in nearby Mott Haven in 2002 and recently opened a gallery, Haven Artspace. “Now there’s food-shopping runs to Fairway so you can get the good stuff,” she says.

To that end, some of what’s going on is the usual upscaling story. The Clocktower, at Lincoln Avenue and Bruckner Boulevard—in the area rezoned in 1997—symbolizes one of Port Morris’s potential futures. It’s a former knitting factory that contains 75 lofts, all but two now rented as residences. Isaac Jacobs of Carnegie Management, whose father started the Clocktower project, says the company bought the building and adjacent lots for $4.75 million in 2000 and finished it this year. He’s charging $900 to $1,600 for units of 700 to 1,200 square feet—sized for professional-class apartment-dwellers, not artists who need space to stretch canvas or weld. The tenants are aesthetically alert, judging by the sculptures outside a couple of their doors, but most of them probably have day jobs. Carnegie even has plans to raze three buildings facing the Clocktower and build another 150 apartments.

The nearby blocks up for rezoning are mostly low- and mid-rise warehouses, all of which could see conversions. Some of them already have artist tenants, living illegally on commercial leases. They withhold their names and worry that rezoning would spur costly adjustments to their space, pricing them out. Representative quote from a resident: “It’s important to look out for the artists, and when someone like you writes an article, it’s a death knell.”

So far, it sounds like Soho in 1974 or Williamsburg in 1992—and we all know how those neighborhoods changed next. But something’s different in the Bronx. The usual gentrification script calls for manufacturing businesses to vanish from a neighborhood as residents pour in, and this part of the Bronx just isn’t headed down that road. Ask Allison Jaffe, a real-estate agent selling single- and multi-family houses for under $500,000 a few blocks inland, on Alexander Avenue. “Port Morris always sat at the crossroads of New York’s commercial routes,” she notes. “So this neighborhood will always retain a kind of mixed culture.”

Unlike prior loft-to-luxe neighborhoods, Port Morris isn’t half-deserted—it has an active, noisy working waterfront. Waste Management runs the borough’s transfer station in the Harlem River rail yards. Other big employers include a New York Post printing plant and the more olfactorily appealing Zaro’s Bread Basket bakery. The Bruckner runs right through the area. “The real issue,” says SOBRO senior vice-president Neil Pariser, “is going to be how residential fits in with industrial.”

The area’s proximity to Manhattan and airports attracts small offices and manufacturers like Antoine Debouverie, a 31-year-old importing laser-cut steel gazebos. Debouverie lives in his 3,000-square-foot Third Avenue loft, soaking up the local character when he’s not traveling on business, and sees the area growing organically. “If you don’t speak Spanish here, you’re not going to have good food,” he says. “The first grab [for housing] is going to be by Bronx locals.” Though the rezoning could theoretically open up the river to a cluster of blah towers, like the ones edging the Queens waterfront and planned for Brooklyn, that’s not likely in the Bronx’s political climate. “I’m not worried about displacement” of businesses, Carrión declares. “I’m more worried that we not create an enclave for high-income-earners only.”

So far, that worry seems somewhat academic. The area still lacks the services and buzz that would stoke speculative construction. Even so, neighborhood residents like Calderón are talking about organizing for low-income set-asides in new developments, and people like Carrión are taking the idea seriously. In short, the borough president is trying to simultaneously bring about change while managing it and making it prettier. His office and nonprofits like Sustainable South Bronx and the Point are trying to fund waterfront greenways and a footbridge to Randalls Island. “The Bronx is bearing the ball and chain from the 1970s,” says Carrión. “Development like this is going to break that chain.” It may. Just not all at once.

Movers

Meet the Brokers

He may look like the quintessential California surfer dude, but Owen Wilson is apparently in the market for a Manhattan bachelor pad. The onscreen buddy of Ben Stiller (most recently in Meet the Fockers) was spotted recently touring the $4.95 million penthouse at 2 Horatio Street, the same one designer Michael Kors reportedly lost in a bidding war in 2003. The two-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bath duplex co-op, said to be repped by Corcoran powerhouse Sharon Baum, has sweeping 360-degree views and a huge terrace perfect for entertaining, should the famously single actor be so inclined. The Art Deco Bing & Bing building—part of a trio where Jodie Foster and Kyle MacLachlan have their New York apartments—also houses the office of the celebrated neurologist and author Oliver Sacks. Both Wilson and Baum declined to comment.

—S. Jhoanna Robledo

Same Space, Different Place

A Balcony by Any Other Name

For the most part, these are identical one-bedrooms in the Lower East Side’s Co-op Village, a mid-century housing project built for union workers, says Jacob Goldman of LoHo Realty. Both measure 800 square feet, are located on high floors, and—big plus—have outdoor spaces. But the apartment at 413 Grand Street has a 120-square-foot “setback terrace”; 383 Grand’s is only a 75-square-foot “balcony.” That disparity is reason enough for a $46,000 price difference, despite the well-known fact that precious few urbanites actually use their terraces. “A setback terrace is more valued because it’s not sticking out of the building,” explains Goldman. “Essentially, it’s a better type of outdoor space.” And almost twice as much room in which to park a dying ficus tree.

383 Grand Street

The Facts: One-bedroom, one-bath, 800-square-foot co-op.

Asking Price: $529,000.

Monthly maintenance: $538.

Broker: Jacob Goldman, LoHo Realty.

413 Grand Street

The Facts: One-bedroom, one-bath, 800-square-foot co-op.

Asking Price: $575,000.

Monthly maintenance: $609.

Broker: Jacob Goldman, LoHo Realty.

—S. Jhoanna Robledo