It takes a certain kind of real-estate market to drive a man to a Brooklyn rooftop in the bitter chill of January, ready to break the law for a chance to have a home. But David Kirchner would tell you his whole life in New York had been leading up to this.

It was two years ago, just a few days after New Year’s Eve, and Kirchner, a 32-year-old freelance film editor, was doing pretty much what he did every day—coveting the abandoned building next door. He’d been fantasizing about the place on and off ever since he and his girlfriend, Courtney Aison, had moved to Park Slope two years earlier. They were caught in a typical New York trap—renting in a neighborhood they loved, but couldn’t afford to buy in—and somewhere along the way, Kirchner got it in his head that this building could be their ticket out of perpetual-renter purgatory and into a home of their own.

The truth is, this wasn’t your typical dream house. The building at 67 Fifth Avenue, near St. Marks Avenue, wasn’t a house at all, but a vacant commercial storefront with two ordinary apartments above it—a three-story brick box on a bustling business corridor. The windows were boarded up, and the metal front door was covered with graffiti. But to Kirchner, who’d been sharing and subletting and couch-crashing in New York for eight years, it was a stately pleasure dome—or at least a potential one. Since the building he was renting in next door was an exact twin, he had a rough idea of what the adjoining property must be like: thousands of square feet spread over three full floors, one already set up to be a store, all going unused. He imagined redesigning the space according to his every desire—the perfect kitchen, maybe a hot tub. He’d be not just a homeowner but a landlord—kicking back while the rent paid for his mortgage. And from his third-floor bedroom window, he could see the building’s lush but deserted backyard, a rose bush growing errantly. What really fed the fantasy was the location. Brooklyn’s Fifth Avenue renaissance was briskly advancing toward his block; before long, two new bistros and a yoga center would open across the street. To the north was the Atlantic Center mall and the site where Bruce Ratner wants to build an arena for the Nets.

If only he and Courtney could afford to buy the place. Kirchner had just $20,000 in the bank, barely enough for a down payment on a studio, let alone a three-story mixed-use home, and as an editor who lived from job to job, he couldn’t carry too heavy a monthly mortgage payment; Courtney was going back to school.

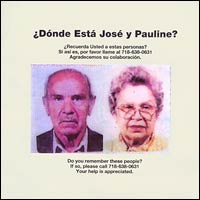

Every morning he would wake up, pondering the essential mystery: Why would anyone give up this building? Kirchner heard from neighbors that no one had seen Pauline and José, the old couple who apparently owned the place, for at least three years. Some said they’d left in a hurry—Spain, possibly; no one knew. He also learned he wasn’t the only would-be poacher on the block. Two people, including his own landlord, said they’d haggled with Pauline over the building. Pauline had apparently flaked out, demanding more money, before the couple vanished.

Most of his neighbors thought the city would get around to foreclosing on the building one day. Then it would be auctioned, perhaps for as much as a half-million dollars. That was a good deal—the land alone was probably worth that—but still too rich for Kirchner’s blood. What Kirchner needed was a steal. Suppose he searched for Pauline and José, tracked them down in some far-off land, and learned that they were highly motivated—desperate, even—to sell? Suppose he made an extremely lowball offer—say, about the same price he would have paid for a studio—and they accepted? “This was my ticket,” he decided. “I’d have the deal of the century, and have a huge place to live in. Even if it’s modest, it’s a place where you could start a family. Where you could have a life.”

Kirchner was the first to admit he hadn’t really thought the plan through: What would he do if he did find Pauline and José—ask them nicely for the keys? Courtney, meanwhile, started worrying that he wasn’t ready to think about having a normal future. Why couldn’t he walk into one of the neighborhood’s dozens of real-estate offices and find a place that was actually for sale? One he could afford?

Between editing gigs, Kirchner started doing recon on the building. He visited the Kings County Courthouse and learned the city hadn’t scheduled an auction for the building yet—despite being owed a few hundred thousands of dollars in back taxes. Until a property is sold at auction, the owners on the deed still have possession. This meant that Pauline and José could still sell the building, paying back their debt and clearing encumbrances like unpaid power bills. This seemed perfectly plausible: “It was obvious that the building was worth much more than what they owed,” Kirchner says. Maybe he actually had a chance.

When Kirchner tracked down ownership records with two names on them—José Barrero and Pauline Dean—his heart skipped a beat. Last names … He jumped onto the Internet and searched the phone listings in Spain. But he quickly learned that to find someone in Spain, he needed a second surname—the matrilineal name—that didn’t appear in any of the courthouse documents. He was back where he started. Worse, he worried that his phone calls about the building had alerted the city that it hadn’t been auctioned yet. Others wanted the place, too, and could pay more for it. If he didn’t find José and Pauline, the deal—if it existed at all—might slip through his fingers. On January 2, 2003, Courtney moved out; they’d grown apart, she said. Kirchner was crestfallen. On the other hand, now there was no one left to keep him from doing what he’d been tempted to do for months. Which explains why, the next day, on that cold January morning two years ago, he broke into the place.

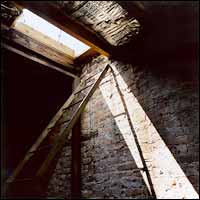

His excited breaths visible in front of him, Kirchner climbed his building’s ladder, leaped onto the roof, and hopped over to the roof next door. The roof hatch was secured by simple pins, which rattled off with only a little encouragement. He looked down and saw Spielbergian shafts of light slicing past the boarded-up windows. He was in.

He thought about going down, but then stopped. What if I fall, break my leg, starve to death, turn into a pile of bones—and whoever buys the building finds my bones? It was a rather transparent fantasy: Not only does he die, he doesn’t get the house.

He darted back to his apartment, called his friend Fabien Pisani, with whom he had dinner plans, and left a message: “If I don’t show up tonight,” he said, “call the authorities and send them to the building next door.” He grabbed a flashlight, a cell phone, and a steak knife—squatters? drug dealers?—and headed up, out, and back down the hatch.

What he saw was at once familiar and bizarre: The top floor had been gutted and was in the midst of being framed out to look a lot like his own apartment. The second floor was the same. It seemed like a construction site where the workers had just left for the day, never to return. And there was a lot of work left to be done. He saw ancient pine subflooring that was warped and bowed—and the ground floor was a disaster, completely unrenovated. Kicking up clouds of dust that got in the way of his flashlight, Kirchner saw a pile of envelopes in a heap beneath the front door’s mail slot. The mail seemed untouched.

Pauline and José apparently had been living on the ground floor while renovating upstairs. They did not live especially well. Clothes were packed away on makeshift racks. Kirchner kicked open the door of a side room and saw a tiny kitchen and living space with a daybed, its mattress so well worn that it still had a body-shaped imprint, and he could see the oily residue from someone’s head. There was a Pompeii aspect to the place, everything frozen in time.

Kirchner left through the hatch; he didn’t want anyone seeing him come out the front door. That night, he told Fabien what he did.

“You are a crazy man,” Fabien said in his thick Cuban accent. “But keep me posted.”

Kirchner went back practically every day after that. He found the keys in a little bowl on the kitchen table, and he worked up the nerve to go in and out through the front door. “In a way,” he says, “I now had possession of the building.”

A week or so later, Kirchner’s investigation hit a wall. His courthouse leads were running dry. He’d run out of neighbors to grill. The time seemed right to commit another crime. He gathered José and Pauline’s pile of mail in a large trash bag and went through everything. He found takeout menus, mostly; a warning letter from a city marshal; letters from agencies that monitor the foreclosure lists, offering cash for the building. “Competitors,” Kirchner says. Others were notes from neighbors making similar offers, often in broken English: I am not trying to steal your building. I want to offer you fair marketable price …

“It was ironic,” he says now. “I had this kind of disgust for that whole approach—sharks circling a wounded seal or something—but I’m on the inside, kind of snickering. These people were idiots—you’ve got to get in the building.”

In the kitchen garbage can, he found a real clue—a 1998 wall calendar that laid out the final six months of José and Pauline’s lives in New York. It had doctors’ appointments, physicians’ names and numbers, and information about a closing of another building the couple had sold on Vanderbilt Street, a few blocks away. “Which I knew about, because I had run their name through the deed department.” He called all the doctors, and after a certain amount of pestering—I’m a concerned neighbor, and I think something might have happened to them—one relented and told Kirchner that Pauline had indeed been ill, with breast cancer that had metastasized to her brain. As of 1998, her doctors believed she didn’t have long to live.

Behind the oven, Kirchner found a half-burned letter from a Madrid branch of the Spanish bank Banesto. It had an account number and Pauline’s second last name, García. The letter was a notice of a transfer into the account of $125,000, just a few months before José and Pauline disappeared. Kirchner figured that Pauline and José must have sold the building on Vanderbilt, made a profit, and camped out temporarily in the Fifth Avenue property. They marked time there waiting for the funds—and, according to the calendar, immigration papers. On September 3, 1998, the calendar read, “Flight 904 TWA to Spain.” After that, nothing.

Kirchner called Pauline’s bank, but the teller wouldn’t divulge the kind of details that Pauline’s doctor had. Finally, he got a break. Buried underneath a pile of newspapers in a back bedroom was an odd wooden knickknack shaped like a deformed rabbit. The base had prongs for holding keys. One of the ears had a thermometer. Mounted under a circular ring was a postcard with an aerial view of a little village nestled in a green valley. The deformed rabbit must be a souvenir. But from where?

How David Kirchner pulled off a real-estate steal.

1. Scouting

Kirchner had been coveting the empty building at 67 Fifth Avenue in Park Slope from his apartment next door. No one had seen the owners for at least three years.

2. Breaking In

Kirchner made his surreptitious entry through a third-floor roof hatch.

3. The Clues

A calendar, a letter from a Spanish bank, and a mysterious souvenir helped Kirchner identify the building’s owners, Pauline Dean García and José Barrero Álvarez.

4. The Owners

Kirchner posted signs around the neighborhood seeking information about Dean and Barrero.

5. To Spain

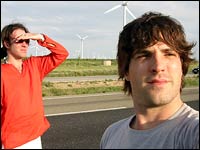

Kirchner, right, and his friend Fabien Pisani traveled to a remote village to negotiate with surviving members of the owners’ family.

6. The Gravesite

Dean and Barrero’s headstones in Spain.

Kirchner pried up the card and saw an inscription: POLA DE ALLANDE. The same words were on a sticker on the souvenir itself. Kirchner thought of the end of The Shawshank Redemption, when Morgan Freeman’s view of a postcard’s beach scene becomes an actual view of the beach, and the camera passes through to find Tim Robbins there, barefoot, warmly greeting him as the music swells. He laughed out loud: This is where they went.

When his friend Fabien asked him where Pola de Allande was, Kirchner told him he’d learned that it’s in an area of Spain called Asturias, west of Basque country—so remote that it was one of the only parts of Spain not invaded by the Moors.

“Dave,” Fabien said. “That is where my family is from. You have got to be kidding me.”

They looked at a map. Pola de Allande is 44 miles from the town of Pravia, where Fabien’s grandfather was born.

“Dave,” Fabien said. “We go there. We find them.”

That afternoon, Kirchner booked two plane reservations to Madrid. Fabien would meet family he’d never met before, and serve as an interpreter for Kirchner. Before they had a chance to leave, Kirchner finally wore down the bank teller in Spain, who told him that Pauline’s account was closed. He gave Kirchner an old address from a town called Oviedo, the capital of Asturias. Using a reverse directory on the Web, Kirchner found six phone numbers at the address. He called each number one by one, using Fabien as an interpreter. Did anyone know an old man with a mustache and a porkpie hat who had a sick wife?

One person remembered. He said they used to go downstairs to Manolo’s tapas bar every day. They called Manolo’s.

“Sí! Sí! I know them!” Manolo told Fabien.

Fabien grinned and nodded at Kirchner.

“Of course I know them!” Manolo said. “But she died. She died two years ago. And he went back to his hometown. Pola de Allande.”

Kirchner couldn’t believe it was coming together so perfectly. Manolo even finally knew José’s second, matrilineal last name: Alvarez. Kirchner quickly typed the name José Barrero Alvarez into the Spanish Internet white pages and got two names. The first one they reached was José’s nephew.

“Ah, I’m really sorry,” José’s nephew told Fabien over the phone. “José died six weeks ago.”

“My heart sank,” Kirchner says. José had died the same week Kirchner first dropped through the roof hatch.

The same day, José’s nephew put Kirchner in touch with a woman named Isabel, a niece of José’s who had taken care of both him and Pauline in their final days. From Isabel he learned their story.

José Barrero Alvarez was a Spaniard who had lived in Cuba for 27 years, then moved back to Spain and finally to New York, where he hooked up with the Cuban expatriate community and met and married Pauline. Pauline Dean García was born in Cuba and stayed until the early sixties, when she defected to the U.S. and started a business in the garment district. They had no children, and spent thirteen years slowly trying to fix up the building on Fifth Avenue, which they bought at an auction in 1986 for $210,000. Isabel said it had been in terrible shape—they apparently got into a bidding war with another party and overpaid. The investment may have been their downfall: They eventually couldn’t pay the mortgage and the rehab costs. Pauline apparently did most of the demo and construction work herself—slowly, painstakingly.

The couple’s marriage was stormy, Isabel said, and when Pauline became ill, she rarely left the La-Z-Boy chair at night. She was superstitious, and she told Isabel she was afraid to die in bed. José suggested that they give up their buildings—she was too sick to work on them, anyway—and move back to his ancestral village in Spain.

When Pauline died, her will specified that the money she made from the sale of their other building, the one on Vanderbilt Street, go to Isabel. But the will didn’t mention the building on Fifth Avenue. Isabel said that when José and Pauline spoke of that building, they said they “gave it back to the city.” In reality, José owned it at the time of his death. Because he hadn’t written a will, it went to his siblings. Isabel told Kirchner that José had two brothers and five sisters, all in their seventies and eighties. Six of them lived in and around Pola de Allande. One lived in Barcelona.

To get the building of his dreams, Kirchner would have to negotiate with seven different people and navigate his way in a foreign country, in a foreign language, through two sets of real-estate and inheritance laws. Any rational person would have walked away. But, Kirchner says, “I had way too much invested at that point.”

Kirchner decided that there was at least a little good news. All the siblings were still alive. And with the possibility of a foreclosure staring at them, there was pressure to force them to the table. If they didn’t act fast, they’d make no money off the house at all.

The first thing he did was cancel his trip to Spain. He could just see the family sitting there, eyeing the eager American who flew across an ocean to meet them; anyone who threw money around like that was just asking to have his pocket picked. Then he started to think of what would make it easy for the family to say yes. What if he could guarantee them a painless closing, in which he’d deal with all the bureaucratic nightmares and any unseen tax and land-transfer headaches? “My thing was, ‘I’ll deliver it to you on a platter. Don’t even lift a finger,’ ” Kirchner says.

He made a lowball offer of $290,000—about a third of what the building might sell for on the open market. Since the city was owed $240,000 in taxes and liens, that would leave José’s seven brothers and sisters $50,000, or about $7,000 each. He told all this to Fabien, who told it to Isabel in Spanish, who in turn told José’s seven brothers and sisters in Spain. The family seemed responsive.

With just $20,000 in the bank and a modest freelance income, how was Kirchner going to afford a $290,000 building—plus untold thousands more for renovation? The idea was to scrape together $29,000 for a 10 percent deposit (he’d get the extra $9,000 from friends or family), then get a construction loan against future rental income from the store and one of the apartments to float him enough cash for the renovations. Once the building was done and reappraised at market rate, he could refinance the loan and use the rental income to pay the mortgage. Rents on Fifth Avenue were exploding; any lender would recognize that.

His lawyers, meanwhile, told him he was out of his mind. What if the renovation costs spiraled out of control? What if the title search revealed a problem that prevented the sale? What if the family backed out at the last minute? “I would go through my savings just to get to the point where they’re gonna say, ‘Thanks so much for setting this all up. We’re gonna go with someone else.’ ”

Which is almost exactly what happened. A week or so after reaching an oral agreement with the family, Kirchner got a call from their lawyer in Spain. “You’re not going to believe this,” she said. His offer was being declined by María, a daughter of one of José’s sisters. It got worse. María was coming to Brooklyn in a week to sell the place—maybe to him, maybe to someone else. He reached María on the phone. She spoke English in an elegant Spanish accent; her tone was aloof and knowing.

“David, thank you so much for bringing this to the attention of my family,” she said. “But I think we can do better. I’m coming to Brooklyn, and I’ve heard you have the keys. I’d like to meet you and deal with this on my own.”

María lived in Barcelona. She was well educated and had a good job. The family saw her as a leader. And she smelled a rat.

Kirchner booked a flight to Spain immediately. The new plan, if you could call it that, was to surprise the family, show them pictures of the place and how shabby it was, hold up the bunny artifact with the postcard, and make them believe in the kismet that Kirchner believed in. He recognized the potential for disaster—“The fear was that they’d sense panic,” he says—but he was desperate.

On April 27, Kirchner and Fabien flew to Madrid, rented a car, drove to Oviedo, and then went on to Pola de Allande. They stopped at a café, and Fabien called Isabel from a pay phone. From three feet away Kirchner could hear “¿Qué? ¿Qué? ¿Qué?” through the receiver. Isabel met them there and brought them to her place; then they convoyed to the Barrero ancestral home.

Kirchner and Fabien entered the old stone house through the kitchen. Only two of José’s siblings were there, the brothers Manuel and Constantino. Manuel, the oldest brother, was frail and emotional. Kirchner and Fabien were told not to upset him by mentioning José; he stayed in the kitchen. But Constantino and his wife, Valentina, greeted them in the living room, along with not one but two nephews with the name José.

No one spoke English, so Kirchner relied on Fabien to field the questions. The chief inquisitor was not Constantino but Valentina. “She was intimidating,” Kirchner says. “You could tell she wore the pants.” Fabien made the case: All Kirchner was looking for was a home, and he was the perfect person to turn José’s building into something to be proud of.

Eventually there was some laughter. Valentina gave her guests a tour, and showed them some things once owned by the late José. When Kirchner and Fabien left, Kirchner had no idea what had been said.

“You cannot believe,” Fabien told him. “There was so much going on. Just know that you made a good impression. They want you to buy the house. But you have to go through María.”

Fabien and Kirchner drove through the night to Barcelona. Kirchner knew the price would go up; he just needed it not to go up to market value. For all that effort, he told himself, for four months’ work, I deserve a discount. In Barcelona, María was expecting them. They had a long dinner. Kirchner learned that visiting her family had made all the difference. María had adopted a tough bargaining stance only because she felt she owed it to her family to seek the best possible deal. In fact, she didn’t really want the pressure of starting from scratch and looking for buyers. Kirchner’s visit to the family had convinced them that his intentions were genuine, she told him. They agreed she’d come to New York and they’d get the deal done.

Besides, as María told him with a seductive smile and disturbing certainty, “You’ll pay more.”

The following week, on May 3, 2003, María and her husband visited the Brooklyn building that her uncle and aunt had left behind five years before. Kirchner was their guide. After a twenty-minute tour of the place—“You have a lot of work to do,” María said—the trio proceeded to the River Café, where, in the final minutes of a marathon lunch, they agreed on a purchase price of $400,000.

The contract took until November 2003 to be signed—Kirchner’s lawyer told him he’d never seen such a complicated title report—and Kirchner didn’t get financing until last May. The money came from the unlikeliest place: another ex-boyfriend of Courtney’s. Ian Clark is a D.J. who had been looking to buy in Brooklyn for some time. “He had the resources, but didn’t have the energy or the time,” says Courtney. “And I knew that Dave was pulling his hair out. They were perfect counterparts.”

Kirchner and Clark now own the building together. Clark secured financing for the initial $500,000 mortgage—the purchase, plus soft costs, like architect fees and the costs of a condo conversion—plus additional construction loans totaling about $420,000 for renovations. Under the terms of their agreement, Kirchner will buy the top-floor condo back from Clark after the renovations are done (Kirchner will have to get his own mortgage for his own apartment); Clark will own the second-floor apartment, and the two will each own half of the ground-floor store, which will be a wine shop run by another friend.

Kirchner’s dream may have been downsized somewhat, but the renovations are his new white whale. Work started in July of last year and was supposed to end in December. Now it’s looking like March. For a time, the architect left the job because Kirchner was making too many changes. He’s added a fourth-story loft level to his apartment; he’s redesigned the kitchen four times (the latest plan includes two different sinks); he bought a Duravit-designed toilet bowl, shaped in the letter D, from eBay; and yes, there will be a hot tub. In January, the general contractor died, leaving Kirchner personally supervising five subcontractors.

When all is said and done, Kirchner and Clark expect to sink $1 million into the building, renovations included. The way the neighborhood is booming, they think they could sell the finished building in a few years for as much as $1.5 million.

Kirchner has a snapshot of him and Fabien from their adventure in Pola de Allande, standing in front of windmills. It took until they got home for someone to point out that Kirchner was Don Quixote. The comparison should have made him laugh, but it unsettled him. Was the dream really worth it?

“I have mixed feelings,” Kirchner says. “The important thing is, I’m in. And I did grow up, but not in the way I thought I would. Now I think about the noise from the buses going by and whether that affects the value of my property. I think about how there are no trash cans on my block and how that might affect what I can charge for rent on the store, and who to talk to on the community board about it. The first part was something of a fairy tale. This is about everyday battles.”

The dividing line between the two, he says, “was the day I actually owned the thing.”