There’s an old urban phenomenon taking on a new form in and around Manhattan, and you have probably seen it, even if you didn’t know exactly what you were looking at. Consider the now-famous three-block section of Bleecker Street that runs between West 11th Street and West 10th (that may not sound like three blocks, but it is). With its immaculate rowhouses and lush trees, it could be Paris, and it now has the shops to prove it. There’s a Lulu Guinness store, filled with $400 gold suede heels, and a block over there’s Cynthia Rowley’s flagship store, with her pink metallic shoes and diaphanous dresses. NYU students flock to Intermix to buy slinky-hipster fashion on their parents’ credit cards, and there’s a Robert Marc store with chunky architect-style eyeglasses. Ralph Lauren has two stores facing each other—men’s and women’s—and Marc Jacobs has a rather amazing three stores, all within eyeshot of each other.

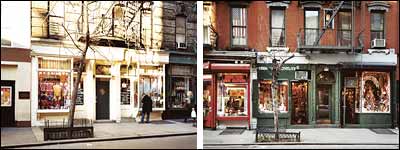

For years, these blocks were more or less indistinguishable from the long eclectic mess of Bleecker, studded with delis, laundromats, a bricked-up dentist’s office, and a handful of sleepy antiques stores. But four years ago, it began to rapidly transform after Marc Jacobs opened up his first shop. Within a year, the stampede was on, as high-end retailers sensed a Hot New Thing and rushed to grab a piece of it. Now Vanity Fair gushes over how chichi the strip has become (“the new Nolita”), and Upper East Siders wander down with their nanoscale dogs to browse the $800 handbags. Young, hip mothers push Bugaboos and sift through cashmere sweaters after lunch. On the weekends, the tourists and out-of-towners descend in droves. As do the celebrities: Julia Roberts and Scarlett Johansson and Sarah Jessica Parker, a local who is practically a fixture.

Real-estate agents shake their heads in amazement. “Soho took fifteen years,” says Gene Cordano, a Halstead agent. “This only took three.” Cordano says he gets calls every day from retailers begging him to find them space down on Bleecker. To them, merely being in “the Village” isn’t meaningful anymore. They want to be part of those three blocks, and those three blocks only. “It’s so European,” says Khajak Keledjian, the owner of Intermix, who fell in love with it while Rollerblading nearby. “It just feels like a cohesive whole,” says Cynthia Rowley, who’s even moving into an apartment a few blocks away. “It feels like a neighborhood.”

More precisely, it’s a “microneighborhood,” and it is now the defining trend of New York real estate. In the world of Manhattan business, the idea of a big, overarching district like Soho or Chelsea or the West Village has lost distinction. When retailers want to create a zone of hipness these days, they synthesize it from much, much smaller atoms: a couple of blocks. Hell, maybe only a single block. Examine almost any area of Manhattan these days and you’ll find it balkanized into a set of breakaway microneighborhoods, each one proclaiming its unique character. The Village has arguably broken into a cluster of microneighborhoods: the sex-shop strip of Christopher; the restaurant corridor of West 4th Street; “Westbeth,” the early-adopter theater-artist zone on Bethune, “a whole neighborhood named after two blocks,” says Seth Kamil, founder of Big Onion Walking Tours. Meanwhile, down in Soho, Furniture Row has sprung up on Broome Street. In Brooklyn, tiny Dumbo has gone from being a weird acronym to a bona fide brand. The speed at which the microneighborhoods emerge has accelerated so quickly that some have already faded into history—such as Silicon Alley, which briefly occupied a stretch of the Flatiron district.

Soho took fifteen years to become a handbag colony. Bleecker tookonly three.

In her 1978 book Metropolitan Life, Fran Lebowitz argued that New York was becoming so wildly upscale that individual blocks around it would soon be given their own names, like feudal lands. (She helpfully coined terms like “Bejelfth” for a stretch of West 4th between 12th and Jane.) That isn’t a joke anymore. “It’s unbelievable how fast people slap identities on these tiny strips,” Kamil says. “It’s sort of a philosophical question: When is something ‘discovered’? When does it officially exist? When someone thinks of a name for it?” And indeed, these microzones can seem almost like parodies of Manhattan’s love of exclusivity. James Sanders, an architect and the author of Celluloid Skyline, a book on New York in the movies, remembers scoffing in 1995 when he heard about a friend registering SiliconAlley.com. “I remember at the time thinking, Whatever. But in retrospect”—he laughs—“that would have been a useful thing to have.”

In a very real way, microneighborhoods are an aftereffect of Manhattan’s explosive gentrification in the nineties. It used to be that a real-estate agent or a retailer could “discover” a dowdy neighborhood, clean it up, and give it a fresh new name. By the turn of the millennium, though, pretty much every corner of Manhattan had been colonized. Genuinely “discovering” a full neighborhood is no longer feasible. The only thing left to do? Carve up existing neighborhoods into ever smaller fragments.

Susan Fainstein, a professor of urban planning at Columbia, says what’s happening now is a rediscovery of side streets, because the big avenues of Manhattan—once home to many smaller retailers—have been flooded with chains. “So the little street takes on a new appeal,” she says. Microneighborhoods are also, as observers drily note, very much a creature of real-estate opportunism. “It’s people in real estate creating interest in an area,” says Kent Barwick, president of the Municipal Art Society. “It’s like with Nolita—it got that name for no good reason, really. With real estate, a little renaming helps a lot.”

While the trend has obviously been fueled by an overheated market—not to mention today’s rampant cult of branding—it is neither purely artificial nor entirely new. The “neighborhood” that’s only one block long is a Manhattan tradition, a natural artifact of a city so tightly packed that people refer to “good” and “bad” blocks as if they were entirely different worlds, even if they’re next to each other. The city has a history of tightly clustered strips of like-minded shops, like the guitar stores lining West 48th Street, or the chess purveyors on Thompson Street near NYU.You could almost map out New York by its clusters, new and old. There’s a lineup of wedding-gown stores that have bloomed on East 9th Street, near Third Avenue, and a set of hipster nightclubs—complete with velvet ropes—that have sprung up in the previously dilapidated stretch of Ludlow Street south of Houston. A microhood of Korean restaurants line 32nd Street, near Fifth Avenue, and photography stores have long clustered on 17th and 18th streets between Fifth and Sixth avenues. And as Brooklyn has gentrified, it has produced a bumper crop of microneighborhoods, from the high-end kitsch furniture shops lining Fifth Avenue in Park Slope to Smith Street’s dining corridor, to even a blocklong Arabic renaissance on Atlantic Avenue west of Fourth Avenue, where Afghan shops hawk Islamic texts and clothing.

“Many people think that a retailer would like to be the only one of its kind, that you’d like to be the only shoe shop on the block or the only jewelry store on the street, so you don’t have competition. But it’s quite the opposite,” says Matthew Bauer, president of the Madison Avenue Business Improvement District. Retailers flock together precisely because it creates buzz that delivers business; the ability of shoppers to zip from store to store brings in more traffic, which more than compensates for the increased competition. Bauer recently helped bring together a microneighborhood of crystal boutiques on Madison around 58th Street, and is attempting to rebrand it as the “crystal district.” According to Sanders, this phenomenon is “part of the amazing self-organizing ability of Manhattan. It’s a fundamentally anti-suburban idea.”

See map of Bleecker Street: A tour of three microneighborhoods on one street.

Bleecker emerged from the same blend of organic growth and canny marketing. Yet what’s unique about it is the almost cartoonish exclusivity of its constituent boutiques. The first seed was planted in 1996, when the Magnolia Bakery opened up at 11th and Bleecker. “It was supposed to be this nice family bakery that closes at 7 P.M.,” says co-founder Allysa Torey. Instead, it attracted the attention of the upscale creative-industry types who had begun to live in the West Village, including the writing staff of Sex and the City, who wrote Magnolia into an episode. The jolt of pop-culture fame brought even more people down, and soon the lines outside lasted until well past midnight.

That’s about when Robert Duffy got interested. The president of Marc Jacobs International, he had lived in the area for twenty years and had fallen in love with the quaint, tree-lined strip. After the first Marc Jacobs store in Soho established itself as a bustling success, he decided he wanted a store next to Magnolia. Given that the nearby blocks were still mostly quiet antiques stores, Duffy knew he’d stand out—a high-end retailer selling $250 sneakers and pimped-out black faux-fur men’s coats—but he didn’t care.

“It was a purely emotional decision. It was not a business decision,” he admits. “But that corner has always been my favorite corner in all of Manhattan. I dined at the Paris Commune, I hung out at the park with my friends. It was what New York meant to me. People thought I was crazy! They thought the neighborhood wouldn’t support it, there wouldn’t be any business.”

They were wrong. The store quickly became a hit with the young locals, and drew fashionistas up from Soho. The first public photo of Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez, Duffy says, was taken while they shopped in the store. Sex and the City struck again, shooting an episode—Carrie Bradshaw’s book launch—there. “It just had this perfect feel,” jokes Cindy Chupack, one of the show’s writers and executive producers. “The street is already art-directed.”

News travels fast among elite retailers: Lulu Guinness, the British designer of bags and shoes, saw Bleecker Street when Sex and the City aired in Britain, got wind of the Jacobs store, and flew to New York to close her own deal. When it first opened, things were quiet, says Charlotte Guess, the store’s first manager. “No one would come in. I’d be banging my head saying, Please, come shop! Then every once in a while, a limo would pull up and an Upper East Side lady would jump out and rush in, afraid of being mugged.” But by the holiday season of 2002, business was booming, and chic designers were storming into real-estate offices to demand leases on Bleecker: first Fresh (cosmetics), then Ralph Lauren I, Cynthia Rowley, then Ralph Lauren II, Intermix, and Olive & Bette’s.

One risk of microneighborhoods is they can devolve into their opposite: microslums.

Rents soared. Real-estate agents say the early entrants in 2001—like Marc Jacobs and Fresh—were getting leases of about $80 per square foot. But by 2003, when Ralph Lauren was opening the first of his two shops, rent was probably about $140 per square foot; by the time he opened his second in April 2004, some landlords were asking as much as $175, says Faith Hope Consolo, who negotiated the leases for Fresh and several other Bleecker retailers. “In just three years, it’s doubled,” she says. Other agents, such as Halstead’s Cordano, are less bullish: He thinks the top rents average only $140. But even that is a lot higher than most non-boutiques can afford. The laundromat that closed when Robert Marc moved in could survive with rent of $50 to $75 a square foot, says Consolo. A place like the Hudson Street Papers card shop could likely handle $60 to $75, and the antiques stores on the strip might be able to go up to about $100. Beyond that is the sole province of boutiques.

There are no lines in the street that mark the borders of the Bleecker mini-boom, but there might as well be. Walk south of 10th Street, and the $300 sweaters abruptly give way to Condomania, a porn-heavy newsstand, and a clearance store with three-packs of discount socks on folding tables and $9 plastic telephones. Why hasn’t the Bleecker renaissance spread? Why is it so compressed?

The answer lies in a few key architectural features. For example, real-estate agents point out that the three-block stretch of Bleecker is endowed with a large number of rowhouses with storefronts. That sets it apart from the surrounding area, where the blocks are mostly residential. Along Bleecker, says Bruce Sinder, the agent who handled the deals for Marc Jacobs and Olive & Bette’s, “it’s one store after another, which is precisely what you want.” Bleecker was perfectly poised to develop the critical mass of retail that Matthew Bauer talks about: an avenue along which pedestrians could spend two hours slowly meandering and comparison-shopping.

What’s more, Bleecker shops are extremely small, less than 1,000 square feet. That influences who rents. Only an elite retailer with high-end goods—or ones they design themselves, for even larger profit margins—can make money in such a tiny space. The Gap needs much larger spaces in which to sell thousands of $10 T-shirts. Bleecker thus imposes a Darwinian logic on the market in which only the hippest luxury goods can survive.

Bleecker also benefits from plain geography. Realtors looked down on their maps and realized that Bleecker was a sort of natural footpath from Soho to the burgeoning meatpacking area, and would benefit from traffic flowing upward as Soho shoppers headed north for cocktails. It didn’t hurt that the local population near Bleecker and Perry had gone massively upscale. Superluxury building like the nearby towers by Richard Meier have brought an influx of residents with advanced spending habits. “It’s creating a mini Fifth Avenue on Bleecker Street,” says Grant King, a Corcoran agent.

Yet no matter how upscale Bleecker gets, it still seems like an undiscovered secret. Retailers say this sense of privacy is why celebrities have felt so comfortable coming to shop. At Intermix, Keledjian has seen the Olsen twins—now nearby Village residents—and Britney Spears come by, and Minnie Driver recently dropped in to get a wardrobe for the Mercury Awards dinner. (She returned later to thank the salespeople for dressing her.)

“If someone is walking on a major avenue, everyone would be flocking on them,” Keledjian adds, while also noting that the environment is changing. “When I see a Japanese tourist with a magazine tear sheet in their hand, and they’re looking for a bag that they read about three months ago”—he chuckles—“it’s coming.” You could argue that Bleecker’s exposure on Sex and the City created a self-fulfilling prophecy. Though that strip of Bleecker wasn’t nearly as tony when the producers first shot there, the show portrayed it that way, prompting chichi retailers to move in and make the street, well, genuinely tony. Life imitated TV.

But perhaps the most important factor distilling Bleecker’s boom is the “border” streets. To the north, Bleecker ends with the ferocious car traffic of Bank and Hudson. To the south, the barrier is cultural: Christopher Street and its sex shops. This is a microneighborhood of its own, the last vestige of the gay stores that used to define much of the Village. Luxury retailers have so far kept their distance. As Cordano puts it delicately, “There’s a distinct feeling of crossing the tracks.”

These two bookends create a super-compressed sense of exclusivity that feeds on itself: The harder it is to get onto the strip, the more everyone wants to be there. To get in, you pretty much have to buy someone out. When Ralph Lauren got wind of the miracle on Bleecker, his people called Sheri Falk, a longtime Village resident who ran Basiques, a store near Perry Street that specialized in French-style linens and clothes, and whose enormous white bulldog famously slept on the shop floor all day long. Falk opened the store a month before 9/11, and the ensuing lull in shopping hurt her. So she made a deal with Lauren. “I said no three times, and they kept calling. The fourth time, I said, ‘How much?’ ” She relocated to Christopher Street, and the following year Lauren opened the first of his two stores.

Real-estate agents now field daily calls from retailers begging to get in. “If I had the space down there, I could do a dozen deals today,” says Consolo, the agent. A Marc Jacobs clerk remembers when the Four Paws pet store next door shut down. Businesspeople rushed in to get the scoop. “They were all like, ‘Do you know who the landlord is?’ Like I’d know. But they were all, ‘We must have it. We must have that store.’ ” Pretty soon, the victor was announced. The new tenant would be a cowboy-hat store by Stetson.

“Stetson?” asks Scott Brush, the owner of Hudson Street Papers, a card shop one block over. “Why would they want to be here?” He’s leaning over the cashier counter, his cat perched nearby, as customers browse through the artist-made cards. Brush is an example of the retailers who have been caught in the undertow on Bleecker, because his ten-year-long lease expires in less than a year. The landlord has warned him that the rent will increase drastically. “I get the sense that it’s going to be so high I’ll have to leave,” he admits.

A young woman in orange-tinted aviator sunglasses and with long blonde hair buys a card and sympathizes. “I’m not so happy about the Guccis and the Polos coming in here,” she says. “It seems like we’re losing our neighborhood feel.”

Brush sighs. “Ralph Lauren needs two stores here like he needs a hole in the head.”

Such is the resentment that accompanies the emergence of a microneighborhood. Rebranding a couple of blocks can seem awfully contrived to the long-term residents, and sometimes it utterly fails. “Remember BeBoMo? That lasted about fifteen minutes,” remarks Seth Kamil, referring to an ill-fated attempt by Lower East Side merchants to give a name to the recent shopping boom on Elizabeth, Bowery, and Mott streets. Even the name “Nolita” has never seriously caught on, says Kent Barwick. A few years ago, Community Board 2 began calling for people to stop using Nolita as a word, arguing that it existed solely to hype property values.

Barwick thinks a microneighborhood succeeds only if it actually reflects people’s emotional connection to their surroundings. He did his own research a few years back, when the city’s Landmarks Commission was trying to figure out whether Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn ought to be called part of Fort Greene or part of Clinton Hill. Barwick went down to Vanderbilt and interviewed people on their way to work, asking them, “What’s the name of the neighborhood you live in?” Not one of them cited any of the commission’s official names. “They said, ‘Atlantic Terminal,’ because they thought of themselves as living near the terminal, north of the market,” he says with a laugh. Another example is Silicon Alley; back when it was the hot way to sell real estate, agents bickered over where, precisely, it was; some desperately redrew boundaries to extend it all the way from Wall Street to midtown in hopes of cashing in on the boom.

For residents, the other risk associated with microneighborhoods is that they can devolve into their opposite: microslums. If the market forces that originally attracted the new stores suddenly decline, those retailers can all vanish in an instant, leaving behind a tiny, blocklong stretch of urban blight. Soho is already experiencing this. Parts of Wooster and Greene are sprinkled with shuttered doors. Longtime residents on Bleecker Street say the danger is even higher there, because the new stores are so similar. If the appetite for $800 handbags were to suddenly dry up, it would decimate that strip the way a single disease can wipe out an Iowa cornfield.

“When the young, hip people suddenly decide there’s a new area, what’s going to happen to all these new stores?” wonders Susanna Aaron, who grew up on Bleecker Street and still lives in the area.

But the phenomenon itself seems unlikely to taper off. For retailers, it’s become a sport to spot the next “It” area and zoom in before someone else gets there first. When he was scouting a location in Nolita for one of his Fresh cosmetics stores, CEO Lev Glazman fell in love with a location on Spring Street so dilapidated that even his real-estate agent had reservations. “It was a former brewery, and when we walked in, there was this big hole to the basement,” says Glazman. “And [the agent] is laughing at me, but I’m saying, ‘Let’s sign a lease right now.’ It’s the same feeling I had about Bleecker. We do everything by our guts.”

If you want to see the next microneighborhood about to pop, walk just a few blocks farther down Bleecker. Between Cornelia and Carmine streets, a crop of luxury-food stores have recently blossomed, clustering around Murray’s Cheese store. In the past few months, the elite seafood retailer Wild Edibles has opened next to Murray’s, proffering $18.99-a-pound Corsican swordfish and caviar-tasting parties; next door, a new Amy’s Bread bakery is set to open. “There’s been so much action here lately,” says Murray’s owner Rob Kaufelt. The local retailers have even discussed luring a vegetable-and-fresh-fruit store to the block, to round out the offerings.

What set it off? Maybe it was Kaufelt’s recent decision to move Murray’s to the other side of the street, a splashy renovation that includes glass-walled cheese caves. Whatever it is, the tiny strip is coalescing, in that peculiar alchemy of the microneighborhood.

The Balkanization of Bleecker Street

A tour of three microneighborhoods on one street.

1. Boutiqueria

Magnolia Bakery started it off, and now deluxe fashion boutiques line these four blocks, including Cynthia Rowley, Intermix, and a his-and-hers pair of Ralph Laurens. Holdouts from the past—antiques stores and the Biography Bookshop—remain only by dint of cheap, long leases or benevolent landlords who aren’t hiking the rent. Between Charles and West 10th, a lone bodega hangs on for dear life.

2. Foodie Court

A gourmand’s paradise has emerged at Cornelia and Bleecker. Murray’s Cheese shop crossed the street, setting up an upscale place fronted with ceiling-to-roof glass and new cheese-aging caves. Now a Wild Edibles seafood market has moved in next door, and an Amy’s Bread bakery is set to open. There is talk of wooing a suitably refined purveyor of precious fruits and vegetables, to round out the high-end food-court effect.

3. The Graying Sex Zone

The blocks in and around Christopher Street are a time capsule, the last vestige of the old, eclectic Village of the seventies. But they also form a cultural border: The chichi fashion strip on Bleecker ends at Christopher, since boutiques prefer not to be next to sex shops with family-size pumps of ID lube. Past Christopher, Bleecker reverts into a more normal New York jumble of dollar stores, restaurants, and jewelry shops.