“Please tell me you’re not moving to Brooklyn,” she said.

“No, no, no,” I said. “Never.”

“Thank God.”

“Why would you think such a thought?”

“Something about the way you said … Brooklyn … like you’d gotten comfortable with it.”

“No,” I said, “it’s just that I’ve had to say it a lot lately because that’s all anyone ever talks about. Brooklyn, Brooklyn, Brooklyn. I hate Brooklyn.”I’ve been having some version of this conversation—the dreaded Brooklyn Conversation—a lot lately. This particular version was with a woman I met in 1988, the year I moved to New York. We’ve been friends ever since—Manhattan friends. We bump into each other in mutual acquaintances’ apartments or noisy downtown parties and occasionally wind up having dinner alone together, lingering over wine and cigarettes. This sort of relationship—genuine but entirely spontaneous—happens more often in Manhattan because, when you take away the nail salons, office buildings, and Central Park, the island really isn’t all that big. Living here is like unrolling your sleeping bag in the world’s largest commune, a year-round camp for similarly neurotic, vain, lonely, ambitious grown-ups. On any given night I could, without making a single phone call, walk out my door and go to a party/bar/restaurant where I’d probably run into someone I know. Or so it seems.

But my Manhattan friend had begun exhibiting all the telltale signs of susceptibility to Brooklyn brainwashing: mid-thirties, recently married, with a new baby. She lowered her voice and sheepishly admitted that, because she and her husband can no longer afford downtown, they recently looked at a couple of places in Park Slope. For a moment I thought, NO! Not her too! It was as if she had been spirited away in the middle of the night and turned into a robot—a Brooklyn Wife, if you will. But then, this: “To be honest, it was my husband’s parents who snapped us out of it. When they found out we were looking in Brooklyn, they threw a fit: We spent a lifetime trying to get out of the boroughs and you want to take us back?! We searched our souls for about two minutes. Now we’re buying a place on 94th, between Park and Madison.” She paused for a moment and then all but shouted, “I’d rather live on the friggin’ anodyne Upper East Side than live in Brooklyn!”

Phew. She had taken sides. My side.

The first time I felt my hackles go up about Brooklyn was last summer at a backyard barbecue in Carroll Gardens. “Oh my God, I can’t believe you still live in Manhattan,” said a new friend, a political consultant who joined the Brooklyn team a few years ago and quickly became one of its most boisterous cheerleaders. With eyes glazed over, I had endured people extolling the virtues of Brooklyn countless times—the party chatter about “how much better” it is and all the fun they’re supposedly having, as if they all spend every Sunday together having brunch at the same “surprisingly good” restaurant. (If it has to be insisted upon constantly, it can’t possibly be true.) But never before had it been suggested that I was a moron for staying in Manhattan. That was it. What was once merely disinterest in that giant expanse of low-slung buildings across the river morphed into disdain and then congealed into bitterness. That was the moment I decided I was a Manhattanite to the core.

Like most people who live in Manhattan, I came here in my mid-twenties because my heart was scalded by some crazy ambition I did not entirely understand. Growing up in South Jersey, I dreamed of Manhattan, that Neverland of glamour, culture, skyscrapers, and reinvention—the place you go to escape from your dreary outer-borough-ness. (And let’s face it: New Jersey is pretty much just a huge Staten Island.) I never once thought of moving to Brooklyn—it was another place people were trying to escape from. This I knew from watching Welcome Back, Kotter as a kid. As the credits rolled over footage of ugly mid-seventies New York, including a big green highway sign that read WELCOME TO BROOKLYN: THE 4TH LARGEST CITY IN AMERICA, the opening line of the theme song by John Sebastian said it all: “Your dreams were your ticket out …” of Brooklyn! I had to be in Manhattan. I’ve always felt a little like Tess McGill in Working Girl. The Staten Island secretary would do anything—lie, cheat, abandon perfectly good friends (she had no choice!)—to find her rightful place in the only part of New York that mattered. My eyes still go moist when I hear “Let the River Run,” the theme song by Carly Simon.

But it wasn’t just career ambition that drove me. To paraphrase Alicia Bridges, I wanted to go where the people danced. I wanted some ack-shouwn. From reading Interview and Michael Musto, I was under the impression that Manhattan was a giant dance floor on which everyone from the skankiest drag queen to Nan Kempner danced their own special dance.

My Manhattan fantasies were stoked by a few firsthand experiences in the mid-eighties. Despite the fact that I’d grown up less than three hours away, I’d never been to New York until I drove here at 21 in my $200 blue ’72 Chevy Nova, which broke down just as I got through the Holland Tunnel. I coasted into a garage and walked around the West Village with an ex-girlfriend who was hoping to be “discovered” as a model. As night fell, we ended up sitting outside at the Riviera Cafe near Sheridan Square. I was dumbfounded by the rush of cars and people, and by the strange things—batteries!—that vendors sold on the streets at midnight. I remember secretly loving the fact that everything cost a fortune and that it could take 45 minutes to go less than a mile in a cab. It was my first clue that Manhattan was not for the faint of heart.

A year or so later, I came to New York with a well-to-do friend who took me to a swank restaurant in a hotel on the Upper East Side and then to the ballet to see Swan Lake. I nearly fainted from intolerable joy as I smoked a cigarette on a steamy August night by the fountain at Lincoln Center. We went back to some friend of a friend’s bachelor pad in an uptown high-rise. I remember whooshing up in a sleek, high-speed elevator to an apartment that was all black lacquer and red carpet. You know what I’m talking about: major stereo, sunken living room, expensive bong on the glass coffee table. I may as well have taken an elevator all the way to heaven. I stood at the window and stared at the sparkly skyline and the red river of taillights streaming down Park Avenue. I was so amped up from simply being in Manhattan that I did not sleep.

“I can’t believe you still live in Manhattan,’’ said a new Brooklyn cheerleader. Never before had it been suggested that this made me a moron.

Shooting for New York, I somehow landed in Atlantic City, a place that, despite its reputation as a dump with casinos, had for me a kind of glamorous decrepitude. It felt like a mini-Manhattan, laid out on a grid on an island, seething with intrigue 24 hours a day. Every morning I went to a newsstand to buy the New York Times solely for the classifieds—I threw the rest away. New York rents seemed laughably expensive, but I promised myself that I would not move until I could afford to live in Manhattan. Settling for Brooklyn or, worse, Hoboken seemed like living backstage, like training half your life to be an actor and then accepting a job as a stagehand hauling the scenery in and out. Miraculously, I got a decent magazine job by answering a classified ad. I found an apartment the same way: a big one-bedroom with an eat-in kitchen on 102nd and Broadway for $550 a month—no fee.

I can barely remember the days of packing and moving because I was in a zombie-like fever dream. When I arrived in New York on Valentine’s Day, 1988, I felt like the family pet that accidentally gets left behind but inexplicably finds its way across thousands of miles to turn up on the doorstep one day, exhausted, a little worse for wear, but so happy. I knew exactly one person who lived here, and the first thing she did was take me to some scary disco in midtown where I saw the performance artist Leigh Bowery walking around with lightbulbs attached to his head and a black woman onstage whose act was to lactate on the crowd.

Naturally, my most avid pursuit as a new New Yorker was going to parties and nightclubs to see how late I could stay out. Being able to stagger away from the wreckage and flop into bed once the sun was high was more than half the point. Manhattan is nothing if not an island of restaurants, bars, and nightclubs—with thoughtful little sleeping quarters just upstairs. It was like owning a time-share in a ski-in, ski-out condo. No need to schlep to the shuttle stop. Just step into your bindings and off you go!

I found myself standing around at parties next to people I’d only read about or seen on TV. One night at MK, Eric Goode’s luxe place in an old bank on Fifth Avenue, Fred Schneider from the B-52’s struck up a conversation. I’ve never forgotten his exit line: “You’ll have to excuse me while I head back into social orbit.” Another night, I wound up at Lorna Luft’s birthday party, thrown by her sister, Liza Minnelli, at some dusty old nitery called Le Club. At one point, Rex Reed began grilling me about how he might get his foot in the door at the magazine I was working for. I ran to the bathroom to use the pay phone to call my best friends back in Jersey. Rex Reed! The Gong Show!

This sort of thing was not happening in Brooklyn. But for one friend who grew up on the Upper East Side and moved to Brooklyn to spite her father, no one I knew ever went there, except occasionally to go to the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Sensible people hightailed it right back to Manhattan and went to Indochine. (Category is … Sentences No One Ever Said in the Late Eighties for $500: “Hey, maybe after that Madonna benefit at BAM, we could go someplace fun in Boerum Hill!”) I know, I know. There were plenty of smart and wonderful people living in Brooklyn at the time, but the point is, I didn’t know them. And I didn’t care! Brooklyn to me was vast and unknowable. I was vaguely aware that the Odyssey, where Saturday Night Fever was filmed, still existed in some Italian neighborhood. And that there was a place called Coney Island that had a roller coaster. But I felt no need to actually go to these places.

This was partly because I was busy having more fun than is legal in Manhattan, and partly because Brooklyn just didn’t come up that often. After the real-estate market collapsed in the late eighties, you could rent a perfectly huge loft almost anywhere in lower Manhattan for a couple thousand bucks a month. In the fall of 1990, after I began to make a decent living as a writer, I must have looked at twenty of them in Tribeca and Soho, each one nicer than the next. I passed up one particularly tricked-out beauty because the guest room didn’t have its own bathroom. Imagine! I eventually settled on 2,400 square feet of wide-open space on the fourth floor of 55 Great Jones Street. Who needed Brooklyn?

Let’s do a little math. If I’ve lived in Manhattan for seventeen years and I can count the number of times I’ve been to Brooklyn on four hands—maybe three—that averages out to about once a year, which, as far as I’m concerned, is once a year too often. I’m kidding! Sort of. Like many people, I have an irrational fear of leaving Manhattan. For one thing, it’s so difficult to get here—to get in—in the first place, it feels like you might lose your spot should you leave it unattended, even for a day. For another, there is the ever-present anxiety that, God forbid, you might miss something. Because we’re all jammed in so tight, stacked up in shipping containers at the loading dock, we all experience everything at the same time, en masse. Even 9/11. New Yorkers who weren’t in Manhattan on that horrible day weren’t grateful for their safe remove; they felt left out.

But in 1988, I went to Brooklyn willingly, because I was only 25 and I didn’t know any better. A friend, who’s now the editor of a fashion magazine, took me to a party in some crummy apartment filled with Oberlin grads smoking pot and listening to “black music.” We were dropped off by a cab in front of a deli on a charmless stretch of Atlantic Avenue in downtown Brooklyn. We went in to buy a couple of six-packs, and there, standing by the cash register, holding court in his bathrobe and slippers, looking like a giant, fat troll doll, was … Al Sharpton! Apparently, he lived in the apartment upstairs, and this was a typical late-evening occurrence. At the time, Sharpton was at the height (depth?) of his Tawana Brawley salad days. It was like bumping into the spirit of Brooklyn personified: disheveled, cumbersome, faintly embarrassing, déclassé, but puffed-up and proud and real. (Today, he’s still the personification of Brooklyn, all polished and professional—and a lot more fun than he used to be.) To the crowd I was with that night—highly educated early adopters of the ironic T-shirt and the million-dollar-dirty-girl look—seeing Sharpton in his jammies was irony nirvana. For me, however, it was a little more complicated. I remember feeling uneasy about the fact that he was a punch line to the hipsters—and more uneasy with each gleeful retelling of the story at the party later, shouted over a James Brown soundtrack. I left Brooklyn that night with a sense that I retain to this day, which is that I cannot ever be one of those people who moves into a neighborhood that many of the people who’ve lived there for years would leave if only they could.

When I hear modern-day yuppies talk of being “pioneers” in certain Brooklyn neighborhoods—so smug in their 718 T-shirts—I want to poke my finger in their eyes. Brooklyn is not a clean slate. People who live there have a history, one that, more often than not, is of grit and forbearance. It’s a history that I imagine the shabby Gentiles of Park Slope and the midwestern hipsters of Williamsburg—colonists, all!—don’t want to think about too much.

But I must confess that I was queasy about Brooklyn even before we ran into Al Sharpton. The moment I stepped out of the cab all those years ago, I was struck by the fact that the strip of Atlantic Avenue looked just like the working-class Philadelphia neighborhood where my mother and her parents were born. What troubles me when I go to Brooklyn, I suppose, is that I see my former self and I see my family’s blue-collar struggle. I was raised in a big Irish-Catholic family. My grandparents both worked in a hosiery mill in Philly until the mid-forties, when they finally escaped to a relatively easier life on the Jersey Shore. There, my father worked for the postal service and my mother was a waitress and a telephone operator and a bus driver. My sister and I were the first in our family to go to college.

By the mid-eighties, my friends from the suburbs of Philly and Jersey were moving into the run-down neighborhoods in Philadelphia that people like my grandparents had left after the Depression. In South Philly, a townhouse with a cement backyard on a shitty block could be had for a song—a jingle!—in 1985. But I wanted no part of it, for some of the same reasons that I don’t want to live in Brooklyn today. Instead of seeing the cute real estate in, say, Carroll Gardens, I see the old Italian grandma in her beach chair on the sidewalk. And she is not romantic to me. She is sad—and far too real. That old lady is my late friend Rita Marzullo, a woman who lived in an apartment in South Philly until she died at 75 last year, alone and broke. She sat in her beach chair on her block and talked to the rotten little bastards who sold drugs on the street because she had no one else to talk to and nowhere to go.

A class-jumper like me can’t go home again. You can bet that Saturday Night Fever’s Tony Manero did not move back to Brooklyn during the dot-com boom because of the “amazing deals” to be had on townhouses in Sunset Park. One of my dearest friends, Joe, grew up in Flushing but came into “the city” regularly as a kid to visit his godfather, who lived on Sullivan Street. Even though he was only 45 minutes away by train, he was hypnotized by the people and the tall buildings. He moved to Avenue B in 1993 and has clung as tightly to his Manhattan dream as any New Yorker I’ve ever met. No amount of indebtedness, rising rents, or threat of eviction will deter him. In fact, when his parents finally moved to Florida twelve years ago, they offered to leave him the house he grew up in. He turned them down. Who passes up a free house in New York City? That’s how much he does not want to go back to the outer borough from whence he sprang.

His story highlights what is unprovable, but probably true: Most of the people who are moving to Brooklyn these days are couples with kids who treat Brooklyn as the new, hip suburbia, or artists and rich kids without the class issues that my friend Joe and I are saddled with. Now that rent control is effectively over, it makes me wonder who will be left in Manhattan once the Brooklyn exodus is complete. My prediction? Old-money families, Eurotrash, newly minted millionaire bankers, and stubborn, overleveraged, delusional, middle-class strivers like me clinging just a little too tightly to their fast-lane fantasies and 212 area codes.

The Brooklyn I first encountered in seventies sitcoms and films, and the one I experienced firsthand in the late eighties, has, of course, changed dramatically in recent years. For one thing, there are, as the Times recently reported, 130 new buildings planned in Williamsburg and Greenpoint alone. Townhouses in once-depressing neighborhoods are selling for millions of dollars. There are glowing Brooklyn-restaurant reviews in publications that used to review nothing outside Manhattan. Then there’s that discombobulating feeling I get when I hear a Manhattanite talk of a crazy night he had in some Brooklyn club I’ve never heard of.

Who will be left once the exodus to Brooklyn is complete? Old money, Eurotrash, and stubborn, delusional, middle-class strivers like me.

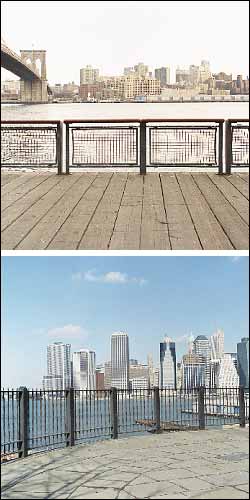

Forced to seriously consider Brooklyn for the first time, I enlisted the aid of one of my best friends, whom I shall call Miss Outer Borough. You know the type: moved to Brooklyn before it was cool; parks her old diesel Mercedes on the street; knows where all the great ethnic restaurants are in Queens; pays under $1,000 a month for a nice walk-up in Williamsburg; prefers Brooklyn because of its “lower density.” She enrolled me in an informal Learn to Love Brooklyn course of her own design. First, I visited her in Williamsburg, where we had lunch. Cute, I thought. An extension of the East Village. But why not just live in the East Village? It’s not that much more expensive. Next we went to Park Slope, where I had never been before. As I recall, I said something retarded like, “Wow, this is, like, a real place! And so civilized! I can’t believe there’s a Two Boots!” But, sheesh, so far away. Next up, Brooklyn Heights, which has the unique problem of looking more like Manhattan than Manhattan. Like it’s trying too hard. And, to take the fun-house hall-of-mirrors aspect one notch further, you can see the entirety of Manhattan across the river, a fact I found both oddly comforting and deeply disturbing. Why can’t we just be over there, in actual Manhattan?

But it was Dumbo that made me think I might actually enjoy living in Brooklyn. Those eerily empty cobblestone streets and the distant roar of the subways overhead and the access to the water spoke to something primal in me. And it seemed that I wouldn’t really be displacing anyone, other than the ghosts of cardboard-factory workers. This was around the time that David Walentas, the so-called Father of Dumbo, was developing the Clocktower building into condos. This could be fun, I thought, and the prices seemed reasonable. Pfffft. That lasted about an hour. My one tiny sliver of a Brooklyn dream shriveled up and died last summer when I spent a day wandering around Dumbo with the singer-songwriter Aimee Mann, who was performing at St. Ann’s Warehouse. Sure, the buildings were there, along with the cobblestones and the water. But everywhere we turned, there were the new markers of pseudo-nostalgia and tasteful affluence. I could practically hear the collective hum of the brand-new $4,000 refrigerators in every apartment, their humidified crispers stocked with mushrooms harvested by Italian monks. As if that weren’t enough, Walentas recognized Mann as we strolled down to the river and thrust himself on us to talk—what else?—real estate!

Even for Miss Outer Borough, the New Brooklyn is harder to love, not least because the dot-com boom turned her beloved Williamsburg into a monoculture. “It was so unprogrammed, so naturally surreal,” she says. “Now there’s nothing that will ever surprise you, because some entity, somewhere, took one Oberlin or Bard grad with a certain collection of books and music and a very exact, ironic, high-low culture taste and cloned that person with infinitesimally small variations, so that Williamsburg now has the narrowest demographic range in the universe, including tribes of people who are all related on the Pitcairn Islands. It’s not that I don’t like the culturati hipsters, but the last time I was in an environment where people only wanted to be with people exactly like themselves was in a fucking mall in Minnesota, which is why I left there twenty years ago.”

But Miss Outer Borough’s real beef is not with the pod people. It’s with the developers who are bringing some of the worst things about Manhattan across the East River. Thanks to one of the largest rezoning projects in New York’s history, dozens of 35- to 45-story towers—Battery Park City, essentially—will likely rise along the Brooklyn waterfront just a few blocks from the heart of Williamsburg. And that’s nothing compared with the rezoning of downtown Brooklyn to make way for the basketball arena, an eminent-domain destruction of a neighborhood that harks back to Robert Moses. As Miss Outer Borough said to me recently, “You thought you hated Brooklyn because it seduced everybody with its wily, charming ways. But you’re going to hate it for a whole different reason, because the forces that ruined Manhattan for young creative people—the rapacious developers—are coming to destroy Brooklyn too!”

In the end, she is right about one thing. I hate Brooklyn. I blame Brooklyn because it has made me like Manhattan a little less. I detest Brooklyn because it has siphoned off so many that I once held so dear and scattered them to the winds in a borough so huge that it has no center, no beating urban heart that I’ve been able to find. (I know, I know. Smith Street, blah, blah, blah.)

Let’s take stock of the losses I’ve suffered thanks to stinky Brooklyn. The first two of my people to go, Diane and Eric, left for Cobble Hill seven years ago. Then they moved to Fort Greene, then to Carroll Gardens. At first, I thought that Brooklyn was just some silly little adventure they needed to get out of their systems, but I have since given up on them. Next, my friend Ricky decamped for Fort Greene. I have never been to his apartment. Let’s see. Who else? Sally fell in love with some cute girl and left a perfectly lovely rent-stabilized apartment in the East Village that she had lived in for seventeen years. I cry when I walk by her old street. Then it was like someone sliced open a vein and Manhattan began hemorrhaging interesting people so quickly I panicked, powerless to stanch the bleeding: Nelson and Liz, Melanie and Andrew, Liz and Ingrid, Dave and P.J., Nicole and Victoria, Cheryl, and, most recently, cute Joe, my handyman. (He’s from Philadelphia; naturally, he loathes Brooklyn.) Even my dear Hilton, a man born and raised in Brooklyn, whom I can only picture smoking a cigarette and drinking a vodka in some smart little aerie in downtown Manhattan, looked at an apartment in Brooklyn Heights recently. “At least the river air was bracing,” he said with a sigh.

I do have a few friends who moved to Brooklyn and, to my great delight, came back. Rebecca took off for Prospect Heights a couple years ago but was back in six weeks because she felt “uncomfortable in big-sky country.” Another friend got a fancy job, married her boyfriend, and bought a townhouse in Boerum Hill; she recently separated from her husband and came roaring back to Manhattan by moving into the Mercer Hotel. Now, that’s a change of heart.

But it’s my friend Ellen who scores the most points. She has never considered—not for one lousy second—moving to Brooklyn. Indeed, she’s threatened to get T-shirts printed up that say BROOKLYN IS FOR LOSERS. As she told me the other night, “I won’t go there! You can’t make me! Los Angeles is my outer borough!”

A couple months ago, The New Yorker caused the tiniest of dustups with a cover illustration that featured two terrified and helpless fortysomethings being banished from Eden, except that Eden was represented by Manhattan and their means of egress was the Brooklyn Bridge. The first thought I had was: I still have not walked across that thing. My second thought: The sparkly eighties Manhattan fantasy of my dreams is dead. And I have to admit that it’s not all Brooklyn’s fault.

For the past few years I have felt myself tuned into some new, barely perceptible frequency. Only recently have I realized that it is the constant hum of a low-grade sadness. The postwar Manhattan experience that I’ve heard described by folks much older than I, and that I’ve read about in books and magazines, and that I myself have experienced in my own time, is coming rapidly to a close. Of course, we’re all acquainted with the romantic and ultimately futile yearning for a place to stay just as we perceived it when we first arrived. But I believe my ache to be the result of something more than that. The parts of Manhattan I have loved—the dirty, decrepit, marginal zones where anything goes—are going the way of the meatpacking district. Which is to say they are being developed into detestable orgies of luxury condos, boutique hotels, stores that sell four things, and curiously uninteresting “hot spots.” In a Manhattan where there was once a nightclub called Paradise Garage, which was exactly what it sounds like, there is now Bungalow 8, also exactly what the name suggests. Exclusivity has become so exclusive that Paris Hilton may soon be the only person who goes out, dancing on a table in a nightclub-for-one, like a plastic ballerina spinning inside a cheap jewelry box.

I recently moved back to Great Jones, into a loft directly across the street from the one I lived in fifteen years ago. The squat building next door to my old place, once Jean-Michel Basquiat’s studio, is now an expensive Japanese restaurant. There’s a new spa up the block featuring a VIP room, a three-story indoor waterfall, and massages that cost $200. From my friend’s apartment across the hall, I can see directly into my old loft, which, but for the furniture, remains almost exactly as I left it. Who lives there? How much is their rent? Are they having as much fun as I did? Doubtful. I was 27 when I moved in with my actress roommate, who was then starring in an Off Broadway hit. We were just young, successful, and stupid enough to be able to really make the most of the square footage. Oh, the parties! I find it almost unbearable to peer into that cavernous old place, like I’m trying to see back through space-time. (Note to everyone: Never move back to your old block fifteen years later.) Ding-dong, Manhattan is dead!

And as for Brooklyn? My boyfriend and I have been talking about moving to B … B … Bucks County! Ha! You thought I was going to concede, didn’t you? Don’t count on it. Despite all of Manhattan’s recent letdowns—the unbearable expense, the ruination of great neighborhoods, the disappearance of favorite bars and friends—I keep choosing the First Borough again and again not merely out of habit, but because giving up on Manhattan would be giving up on the dream. Manhattan will always be the Promised Land; Brooklyn will never be able to replace it in the popular imagination.

Recently, though, something curious happened. We got in our car one Saturday night and drove to Queens to spend an evening out with friends who live in Brooklyn. We parked under the elevated 7 train on Roosevelt Avenue and 71st Street, and I was astonished by how alive, how thrumming with activity and people and variety the streets were. There must have been 30 countries represented on that one block alone. It’s noisy. It’s crowded. There are traffic jams. It takes forever to park. Fun! We drank in an Irish pub where real Irish bartenders treated us like regulars and played the Cure and Beyoncé on the sound system. Then we went to an Argentine steakhouse and were received like the reverse bridge-and-tunnel clowns that we were. I was convinced that the waiter was trying to give us the gringo price on our bottles of wine, but no matter. I had the time of my life. And I will say it here first: I love Queens!