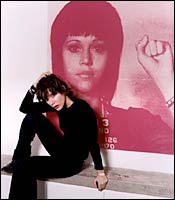

There is no sign outside Sally Hershberger’s meatpacking-district hair salon. It’s too cool for that. Cool in the way “uptown” people imagine things should be south of 14th Street, or in this case, on 14th Street, and west, west, west. The steps outside are standard-issue corrugated metal. The floors are cement, the TVs are plasma, the music is heavy on the bass. After a pretty girl with kohled eyes checks me in, I change in a bathroom with a Warhol over the toilet. And then I am escorted by two handsome, silent guys to the back of the salon, where a wall of windows faces south, and there Hershberger is, leaning against a counter in a pair of perfectly worn Levi’s, her signature Klute–meets–Patti Smith bob tousled just so. She’s wearing a pair of big, seventies sunglasses. She looks up—I think. “Hey,” she says.

I am ushered into a swivel chair, and she studies me carefully. She switches to a pair of horn-rims and furrows her brow. “You’ve got a mullet,” she says, grabbing at chunks of my hair. “I like a mullet.” But not, clearly, this mullet. “Let’s just fix this,” she says.

Thus begins my $600 haircut.

The handsome assistants—Milo (tall, Asian, tapered bob, like a Southern California skateboarder) and Mihe (smaller, buff, with the tendency to purse his lips tightly)—nod emphatically: Four sets of eyes study my head in the mirror. Hershberger likes “cute guys” to assist her, she tells me. “There’s way too much drama with girls.” Milo rushes me to a sink, props my legs on a leather ottoman, and then, before I know it, we’re all back together again and Mihe has begun sectioning my wet hair into little rolls. Hershberger starts snipping away: Four furious hands (one, Hershberger’s, wearing a gold Hermès watch covered in a blinding layer of diamonds) moving in sync around my head, while Milo hovers anxiously in the background. “I’m not the funnest hairdresser,” Hershberger tells me as she cuts.

“Sally’s not really a proponent of making people feel better,” says Sandra Bernhard, a client and friend for the past twenty years. In fact, Hershberger never tells me I have nice hair, or even healthy hair, which hairdressers always do. She just studies and snips and, occasionally, looks at herself in the mirror and ruffles her own hair. She describes her look as androgynous. “You know how Bowie and Mick Jagger weren’t totally masculine?” she says. “I’m like that.”

As she works, she talks unfavorably about the wave in my hair, and then tells me I need a flattening iron, that I should really think about adding some color. “So many women want to go somewhere that, even if it’s a totally gay guy, he’s making you feel sexy and desired and wanted,” says Bernhard. “Which I think is totally condescending. You don’t go in to Sally for strokes.”

Fifteen minutes later, the blow-dryers come out, one on each side of my head. It’s deafening. Suddenly, Hershberger grabs Mihe’s brush.

“Flat!” she cries. “Round is just … not … groovy!” Mihe bites his lip, switches brushes. “Not groovy,” she mutters to herself.

Once my hair is dry, Hershberger spends a few minutes slicing at the ends with a razor, and then I’m done, back on the street. Transformed?

I walk to Pastis to meet friends for lunch—and show off my $600 hair.

“Puff out your lips,” they say, laughing. “You’re Meg Ryan!” But do I look great? Cooler? “We miss your curls,” they conclude.

But when I run into my friend Jose Bravo later that afternoon, he tells me, “Girl, the last time I saw you it was, like, only okay.” He waggles his hand back and forth. “But now you look good.”

High-end hairdressing on the Manhattan-to-L.A. circuit has been a growth business since the days of Vidal Sassoon, but now that Hershberger has opened her eponymous salon—nestled smartly between the Stella McCartney and Alexander McQueen boutiques on 14th Street—and tripled the going rate for a designer haircut, it’s gone into overdrive. As Bernhard puts it, “Sally’s not a celebrity hairdresser. Sally’s a celebrity.”

Hershberger, with her expensive tastes and Da Silvano lifestyle, is the new model for the hairstylist: She’s not a member of a service industry. She’s an artist. It’s rumored that the character of Shane McCutcheon, the heartbreaker hairstylist on The L Word, is modeled on her. “I used to hate to say I was a hairdresser,” she says, “but now it’s like, we make more money than doctors and lawyers.”

The new hairdresser is a wizard with a signature style (“I mean, if you see a Frank Lloyd Wright, you know it’s a Frank Lloyd Wright,” Hershberger says of her signature, the shag) and fiercely loyal followers willing to shell out thousands of dollars a year for buttery chunks, shaggy bobs, and silky blow-dries, who pledge their allegiance with a passion more appropriate to a love affair.

Hershberger’s not shy about her pedigree. “I’m from an upper-class family,” she says. “Not middle class—upper class. My father was an oil producer from Kansas. Have you heard of the Koches? They were our next-door neighbors. It was not the kind of family where people became hairdressers.” Sally was the rebel daughter who ran off to L.A. to surf and listen to rock bands instead of going East to a leafy college.

But nobody would mistake her for a lightweight. “At this level,” she says, “you’ve got to read the paper. You’ve got to be informed. Michelle Pfeiffer does not need her hair cut by someone who doesn’t read.”

The salon is an extension of her hard-glamour world. “I just wanted this place to be, like, the anti-salon,” she says. Hershberger lives in a West Village loft and has houses in L.A. and East Hampton—where she throws legendary triple-A-list parties—but she’s run out of space to showcase her art collection. What’s in the salon are the leftovers.

“Sally,” says Bernhard, “is rock and roll.”

Not surprisingly, her rock-star pricing is decried by many competitors as absurd. “Spending $600 to get your hair cut in the meatpacking district?” says Kenneth Battelle—the legendary coiffeur—with a snort. “That just makes you sound like a meathead to me.” “It’s just a way to announce her arrival,” another stylist sniffs. “I mean, what does she do that anyone else can’t do? It’s just a big fuck you to the rest of us.”

Hershberger, for her part, thinks that’s just rich: “Has anyone told these guys that not everyone can afford $250 either?”

What Sally Hershberger is to the shag, Brad Johns is to chunks. Buttery chunks. If Martin Short were somehow to get his hair to the silky consistency and sun-kissed color of a 7-year-old Wasp after a summer on Cuttyhunk, dress in all black, and preside, like Leonard Bernstein conducting a symphony, over five foiled heads, the result would be Brad Johns. “I invented the child at the beach,” Johns tells me, by way of introduction. He chops his arms for emphasis but his smooth, creaseless, nutty-tan face remains expressionless. “No one was doing golden until I came along.”

He eyes me carefully. “I do do brown, too. I do.” Johns got his start at the late Cinandre salon in 1977, when the acting career he’d moved to New York to pursue didn’t pan out. “When people would ask for a frosting, I would just tell them I’d rather be poor than frost hair,” he says. “Look, some dermatologists specialize in Botox, some specialize in, like, rashes. I chunk.”

Johns has done many celebrity chunks—James King, Vanessa Redgrave—but it wasn’t until the buttery chunks that he really hit it big. As far as color is concerned, few heads were as envied as Carolyn Bessette Kennedy’s. Long and flaxen, her hair was the ultimate embodiment of very expensive, totally high-maintenance, and completely laid-back. “C.B.K. had the best hair in the world,” says Plum Sykes, a dedicated student of glamorous hair. “The ultimate.”

Johns was so proud of his work that Kennedy’s lawyers eventually had to issue a cease-and-desist to get him to stop waxing about it, but in the end it didn’t really matter. The look he’d come up with—“it doesn’t have to look natural, it just has to look fabulous”—was just too famous.

Johns’s attempt at his own salon didn’t work out, so instead he went mass. Clairol signed him to a deal as the brand’s spokesperson. And a few years ago, Avon hired Johns to headline its salon in the Trump building on Fifth Avenue. Wandering its triple-wide hallways and gargantuan waiting area, I don’t feel like I’m in midtown Manhattan. I feel like I’m in an Orange County country club, the kind of place to freshen you up after a day on the links. There are no hard edges, there is nothing that’s not beige.

It’s not surprising, then, that Johns claims a lot of his clients come from elsewhere. He even goes on the talk-show makeover circuit to urge viewers to ask their communities to come on a “color tour” (he charges from $150 to $300—“it’s just so easy, I can’t charge more!”) to New York and into his chair.

“I would follow Brad anywhere,” says Nina Griscom, who’s been a Johns blonde for ten years. “Avon is a little bit, let’s see … democratic.” She offers a delicate pause. “But I’ve never had a bad experience there.”

“By the way,” Johns tells me, regarding my untreated hair like a fungus, “colorists are not people who do color. We’re artists. It’s like, I’m a Picasso, Sharon’s a Matisse. Someone else might be a Gauguin.

“People come to us not to get their hair done. People come to us to buy one of our paintings. Your head is my canvas.”

I ask Kenneth Battelle what he thinks of such grand proclamations. “Oh, come on,” he says. “And when he’s not being a great artist, he’s working on his face to get it to look like Lee Radziwill.”

But Johns understands that the collector of Abstract Expressionism, say, may not be in the market for an old master. “I don’t weave color,” Johns says. And to that end, he’s more than glad to turn clients away. “Sharon weaves color. If someone comes to me looking for woven, I send them to Sharon. If someone goes to Sharon and says, ‘Big! Bold! Gold!’ she sends them to me.”

By Sharon, Johns means Sharon Dorram-Krause. She’s every bit the success that he is—Renée Zellweger, Kate Hudson, Uma Thurman, Linda Evangelista are all devoted to her—but she’s far more mellow. Often considered the Sally Hershberger of color (both headline John Frieda salons and share many clients), she looks a lot like the women she keeps blonde: trim and clear-skinned, with a dazzling collection of diamonds. She wears Helmut Lang loafers, looks divine in a Narciso Rodriguez shift, and is married to a handsome German businessman who drives a vintage Mercedes when the couple are at their house in Water Mill.

“I was a little intimidated to go to Sharon Dorram-Krause,” says Carol Brodie. Brodie is the spokesperson for Harry Winston diamonds and a makeover television regular—she works on Extreme Makeover, and she’s a juror on E!’s Style Court. “It’s like a little club,” she continues. “The woman who goes to Sharon is very chic. You can’t go to Sharon if you only want good hair. You go to Sharon if everything about you is perfect. If you don’t have a good look, why would you go to Sharon?”

Much like Hershberger, Dorram-Krause has a background unusual to hairdressing. “I studied fine arts at Bennington,” she tells me, “and then I moved to Italy. I always figured I’d do textiles for Chanel or something like that.” But then a friend taught her how to color hair. It was so similar to the intricate weaving she already knew how to do. And then she started making a lot of money. “And I really just loved it.” She’s never looked back.

“She leads a lifestyle similar to that of a lot of her clients,” says Lisa Errico, formerly a senior publicist at Hermès who found Dorram-Krause ten years ago, after Brad Johns “turned me orange. Yeccch.”

The idea that choosing the right salon is like admission to the right club is not new. Ever since Vidal Sassoon did his famous “Five Point” cut on Grace Coddington in 1964, it became a truth widely acknowledged that certain haircutters were far bigger than just hair. To have a Vidal Sassoon cut was to be a modern kind of girl.

Kenneth Battelle, meanwhile, was bouffing hair in New York, fashioning fabulously immobile hairdos for Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. “I just think about what Halston told me a long time ago,” Battelle says of the cult of celebrity hairdressers. ‘You’re famous because of your clients, not because of you.’ Of course, you can be famous now, I guess, for giving a $600 haircut.” Battelle still cuts hair four days a week. His price is $155.

These days, the Kenneth salon is run by Kevin Lee, who looks very out of place among the morning Sterno-buffet-goers at Oscar’s in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, though the salon is just one flight up. Lee is polite and disarmingly modest; clearly, he’s learned from his mentor. The feel remains fusty: all chintz and gilt and milky coffee sipped from white china. He charges only $95 for a cut. “It’s a craft,” he says. “And if you do it a lot, you can get very, very good at it. I’m glad that I make people’s days better, but it’s not like I’ve cured cancer here.”

It’s always hard to get an appointment with Lee, but if you’re trying on, say, the evening of a gala at the Frick, it’s near impossible. “I’ve been to a lot of people,” says Tory Burch, “but Kevin is as nice as it gets. I see him outside of work. He’s a friend.” Lee is the favorite hairdresser of 10021, and his close friendship with Michael Kors doesn’t hurt. Because not only does your hairstylist have to make you look great; the ideal hairstylist is also the perfect addition to your dinner party. If there’s anyone who knows how to work a social life to his advantage, it’s Frédéric Fekkai. “Look,” says Fekkai. We’re sitting at a raw-wood table in his new corporate headquarters overlooking Union Square. On the wall behind him are shelves and shelves of his products: pale-yellow conditioners, creamy peach shampoos. “A lot of people do a good haircut. You can’t just talk about hair.” With his olive skin, blinding Chiclet teeth, gleaming swoops of thick brown hair, his five-story salon above the Chanel store (his brand is a joint venture with Chanel) on 57th Street, his outposts in Los Angeles and Palm Beach, Fekkai, or at least the Fekkai method, touches more heads than any other high-end salon. “It’s not a salon,” he says. “It’s a brand.”

The Fekkai look is not edgy or rock-and-roll. “You don’t see the seams,” he says, making it the exact opposite of a Hershberger or John Sahag or something from Bumble and Bumble, where jagged edges strive to look undone. A Fekkai client should be able to go to any of his salons and receive a snipping from any of the handsome, flirty, heavily accented men wearing Lacoste shirts he employs and not notice all that much difference. “We start at the center of the head. It’s an orange-peeling technique. You lift hair straight, you cut it in a perpendicular way. There is a consistency, a methodology, a making sense.”

This, perhaps, is why other hairdressers waste no time in sniping about Fekkai’s skills. “Let me see how to answer that,” one hairdresser says cattily when asked about the Fekkai technique. “I have tremendous respect for Frédéric. As a businessman.”

“I really learned from business people. Hotels, resorts, even Disney,” Fekkai says. “You have to learn hair, so you learn it. But if I do not have a sense of business, I become a mom-and-pop.”

Fekkai sees his mission as making clients feel gorgeous. It’s hard to believe that the stylists in his salon, with their mocking eye contact and spontaneous shoulder rubs, have not been instructed to flirt. “I’m sure he makes them do it,” says another hairstylist of the flirting, “especially if they’re gay.” Fekkai himself has courted many of the rich blondes who’ve trusted their tresses to his care: Patricia Duff, Libbet Johnson. “He’s very nurturing,” Duff says. “It’s like he’s looking out for you in the big picture.” Fekkai cuts hair only a few days a month, and when he does, the price tag is $400, but he’s trained his boys—long-haired men with names like Fabrice and Cedric—well. I’ve never gotten my hair dried at Fekkai without the stylist bending down, so we are chin-to-chin, and puffing out his cheeks as if to say, “Well! Look at us!” “When hairdressers in my salons are successful, they really have a lot of self-esteem and confidence,” Fekkai says. “And they have status. Because being a designer at Frédéric Fekkai is not like being a hairstylist.”

Sometimes this “status” just isn’t enough. In 1997, three of Fekkai’s top stylists decided they didn’t want to cut orange peels anymore. They defected and formed Salon AKS. “After watching someone else for a long time, there are definitely things you would change,” says Susanna Romano, the S in AKS. She nervously eyes her partners. “We didn’t hate working there!” says Alain Pinon quickly. “He’s got a system. We wanted to try something else.”

Such defections are pretty common in the business. It seems that every top salon has its spinoff: For Fekkai, there’s Salon AKS; ex–John Sahagites can be found en masse at Eiji twenty blocks north of their former home. Last year, three stylists from the John Barrett salon formed Butterfly in Chelsea.

Barrett has survived worse. When he took the reins of the salon at Bergdorf Goodman from Fekkai in 1997, he brought with him a dazzling British clientele that included Princess Diana. But a year later, he was hit with a $124 million lawsuit by four male employees complaining of sexual harassment, including the allegation that he had squeezed the receptionist’s nipples so hard it hurt to take a shower.

Bergdorf supported him, he got past it, and Barrett went on to earn an exalted position in the pantheon of hair. “Out of all the salons I’ve been to, John Barrett is the most sceney,” says Plum Sykes. “He always has, like, five Brooke De Ocampos in there at once.” It’s no wonder, then, that Sykes set her first novel, Bergdorf Blondes, in the ninth-floor salon, with its lilac walls and cherry blossoms.

“It’s a hard business,” says Barrett, a tall and affable man from Limerick, Ireland. “People keep moving around. Every year, every salon loses a certain amount of staff. And people get so dedicated that they wind up going five different places: cut, color, manicure, pedicure, eyebrows … ”

Barrett’s appeal is one of understatement. “My look is more subtle than overwhelming,” he says. “You’re not coming here to get punked out.”

Serena Bass also likes Barrett’s devotion to a client’s total look. “When I put on too much weight, John told me I wasn’t allowed back in the salon until I’d lost it,” she says. “I’m not as good as Fekkai at the cocktail-party circuit,” Barrett laments. But he definitely knows how to coddle the famous girls. “When I first moved to New York, I absolutely hated it,” says Sophie Dahl. “And I know it sounds rather naff, but once I met John and started getting my hair done at his salon, I felt like everything was going to be all right.”

If you talk to elite hairdressers long enough, you’ll hear unkind words about all their competitors. Except John Sahag. So I decide to give him a try. At Sahag’s Madison Avenue salon, the mirrors are all flanked by anemic stalks of bamboo. The cement floors and walls are covered by lumpen, gray, papier-mâché “rocks,” through which dribbles the occasional “stream.” Sahag comes out to greet me in skinny leather trousers and a shiny rayon shirt unbuttoned to the belly button. A heavy silver medallion is tangled in his chest hair. On his head is a long brown mullet—he’s since shaved it off—blurred by static electricity. He circles me for a while, reaching out occasionally to run a finger or two through my hair.

“Darling,” he says, smiling encouragingly, “how about some wine?”

When you’re cutting, Sahag tells me, “you’ve just got to go … there.” Where? “There.” He puts his hand in the air and waves it vaguely, squinting in the distance, before balling his hand into a fist and bringing it to his heart and smiling. See?

“In ten to fifteen years, everyone in the world will be doing the John Sahag,” he says. What he means is that everyone will cut hair dry, like he does. “When hair is dry, it’s a very visual event. Wet, you’re cutting all the magic away. And there’s nothing like a cut with magic to it. See, when you go there, you create new shapes. And it’s in carving new shapes that you find the unique shape that matches the soul—the cheekiness, the naughtiness.”

He smoothes my hair with a blow-dryer and gets to work. Fifteen minutes later, he’s done. He bows and walks off. A short assistant, who’s been hovering with extra scissors and a deeply concerned expression, whisks me to another chair. He washes my hair, fills it with gel, diffuses it. I spend the ride to the West Village desperately smoothing matters down with the palms of my hand. I call my chic friend Anne. “I think I have a mullet,” I tell her. “Has John Sahag ever cut your hair?”

Anne laughs. “Yeah,” she says. “In the eighties!”

Janet Carlson Freed, the beauty director of Town & Country, is terribly devoted to Sahag. “I knew with an artist like John I would be cheating myself if I told him what to do,” she tells me. So, was she happy with the result? Not right away. “At first, I didn’t understand it. But he has a vision.”

“Here’s the thing about hairdressers in New York, darling,” says Plum Sykes. “There’s a very big difference between who you say you go to publicly and who actually cuts your hair. Some of them are so terrifying, you just have to say you go there.”

Look, Sykes loves John Barrett enough to go there for a “really fabulous blowout” and various grooming etcetera (“The most fun I’ve ever had with my boyfriend was taking him for a pedicure at John Barrett”), but when it comes to a cut, she wouldn’t dream of letting anyone but Paul Podlucky near her with a pair of shears. “He cuts Aerin Lauder’s hair, too,” Sykes points out. “And I die for her hair.” He also does Victoria and Vanessa Traina (Danielle Steel’s daughters) and several Middle Eastern princesses who came with complicated confidentiality agreements.

“It’s true,” Podlucky says. I found him in the small one-bedroom apartment on East 67th Street where he lives and works. I’ve just told him what Sykes said. “Always the bridesmaid. It’s like everyone goes to Frédéric.” He rolls his eyes and puts his fingers in the air in exhausted little quotations over the name. “But I’m the one who does the cuts. I am. John Barrett gets so mad.” He brings me a perfect cup of green tea on a saucer. “It’s funny, ’cause I’m a Leo,” he says, gazing out the window at a sliver of Central Park, “and Leos need lots of acclaim for what they do. I guess I’m just not that kind of Leo.”

Podlucky’s clients like him for the total privacy he offers, even if it means they get changed in his tiny bedroom, lean back for shampoos in his bathroom sink, and have to put up with his three flatulent dogs.

He does fourteen heads a day—$200 for a cut, $165 for color—starting at 7 a.m., and there’s a six- to eight-week wait for new clients. He does color himself. He also does makeup, and he’s available (for $750) to come over before a night out to get his girls perfect. “I’m just diseased to please,” he says. Podlucky’s cuts are simple, classic, and polished. “No one understands that it actually takes forever to have hair like this,” Sykes says. “You just thought my hair was gorgeous and easy, didn’t you? But if I didn’t go to Paul, I’d have triangle-head.”

Podlucky definitely makes his clients feel good. Sipping my green tea in a quiet patch of yellow sunlight, I’m loath to leave, but his next appointment has arrived. He gives me a giant hug, offers me cab fare. “Can we cut your hair?” he asks. He runs his fingers gently across my scalp. “It would be great because you are like the perfect combination of Marlene Dietrich and Elizabeth Taylor.”

Oh, Paul! Really?