“No money, no come-y,” says Stephanie Winston Wolkoff into her constantly ringing cell phone. She’s just about had it with explaining that the Costume Institute Ball’s after-party isn’t a laid-back, stroll-past-check-in kind of night.

Last year, there had been some … problems. At 10 P.M., after dinner, the unwashed, unjeweled, distinctly unfabulous hordes had descended, gawking at the celebrities. It was like the scene at some dank West Side nightclub. She is taking pains not to let that happen again.

So later in the evening, once Renée Fleming has completed her performance (it’s just over seven minutes—Wolkoff has timed it), the doors will open to just 400 (society girls and their purse holders), and Wolkoff’s got a directive to keep the numbers firm. She’s up to her ears in big fries—“We have some dignitaries, we have some excellencies. We have the French”—and she’s not hearing excuses from anyone.

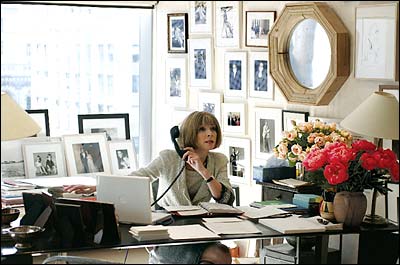

The staff at Vogue, the staff at the Metropolitan Museum, and the employees of any place rich enough to have doled out $150,000 for a table like to think of the Costume Institute Ball, held this year on May 2, as a sort of Oscars for the East Coast, by which they mean the Oscars, only much cooler. “At the awards shows you really get Hollywood people and the press,” says Vogue editor Anna Wintour—the unspoken thought being: That other party is, maybe, a little dull.

Wintour is sitting at her desk overlooking Times Square, in a black-and-white Chanel jacket whose tweed is ticked with small, light-reflecting paillettes. Wolkoff is out the door and shouting-distance away, a phone on each ear, manipulating 700 Post-it notes—a socialite Bobby Fischer—but in Wintour’s office all is calm, a self-important hush. Wintour never says more than is absolutely necessary. She’s fearsome and oracular; most often, her subjects attempt to divine what’s in her mind, or face the consequences. She plans this party with the help of Emily Rafferty, the similarly smooth-tempered well-kept president of the Met, and Vogue’s Wolkoff, who, tall and clear-eyed, is a popular member of what Wolkoff calls “the socials,” the Upper East Siders who are happy to pay for their tickets.

André Leon Talley, Vogue’s regal, supersize editor-at-large, on the other hand, is more than happy to say more than is strictly necessary. “With total modesty, I’d say that this is the most important social and fashion party of the year,” he pronounces, and then goes on to elucidate the ways in which the Costume Institute Ball is superior. “The fashion is more confident,” he declares. “It’s not some haphazard stylist saying suddenly, ‘Oh, you should wear this.’ Women like Lynn Wyatt know who they are.”

At the Costume Institute Ball, it is real taste that counts. It’s a party that launches a thousand shopping frenzies, with decisions and revisions that a minute will reverse. Every starlet and grande dame is searching for the perfect dress, and every designer for the perfect woman to hang it on. On the day of the event, everyone (even Anna Wintour herself) takes a room at an uptown hotel, like the Carlyle or the Mark—do you have any idea how wrinkled a dress can get in the backseat of a car?—for prepping and primping, a last-minute vanity extravaganza.

The real taste is paid for with real money. The 700 guests at dinner all have to be accounted for—either individually, with tickets ranging from $5,000 to $15,000, or as guests at tables taken out by corporate sponsors. The tables cost $150,000, and they’re covered up front. The money raised from the sale of tickets—last year, the figure was some $3 million; this year, Wintour and her legions are aiming for $3.8 million—constitutes the Costume Institute’s entire annual budget. The tab for the party itself—which those who would know estimate at about $2 million but Vogue claims is far lower—is covered by Vogue and Chanel. A fair price, when you consider, as Wintour does, that “those pictures go around the world for the next year.”

The party is a beyond-ostentatious union of Upper East Side money, Hollywood glamour, fashion, and fine art. And like any good marriage, everyone gets something out of the deal. It’s true that in certain quarters of the Metropolitan Museum, all that decorative plumage is viewed as a little indecorous, and the slavish pursuit of fashion-company dollars as a crass substitute for the good old-fashioned pursuit of superrich benefactors. At some level, the party is a giant commercial for Chanel and Vogue, with the Met providing the billboard space. Met director Phillipe de Montebello himself is said to look askance at the Costume Institute. But in the end, the Metropolitan is happy to overlook the implicit commercialism. After all, it gets to play host to a lot of those superrich benefactors. And amid all the bedazzlement and air-kissing, who would be so crass as to mention a little thing like commercialism?

Chanel and the Met had been circling each other for several years before tying the knot. The idea to devote an exhibit to the label first came up in 2000, during what was a controversial time for the institute. Its beloved director, Richard Martin, had died, and an interim curator was in place. She was roundly denounced as terribly unchic by much of the fashion community. “Her name was Myra, and Anna never even learned her name—she called her Myrna,” says a Met employee.

Wintour typically plays a key role in approaching and securing the event’s sponsor, and without her avid matchmaking, the 2000 deal fell through. Many have said that the Met was concerned about the super-high-maintenance requirements of Chanel’s creative director, Karl Lagerfeld. But last year, the situation changed. One impetus was that the “Dangerous Liaisons” party, as it was called, was seen by many as the moment when the sublime became the ridiculous—a whole French court full of fashion victims. Changes had to be made. For fashionistas, Chanel is a safe, impeccable, forever stylish choice—precisely the theme that the Costume Institute Ball needed.

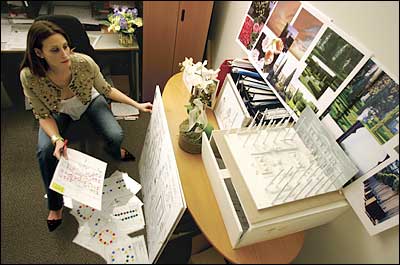

At the Vogue offices, the planning for the Costume Institute Ball goes on with the intensity of a trading floor, with Wolkoff, Vogue’s director of special events, as the hard-bitten, all-knowing head of arbitrage. She knows who you’re dating, who you’re not dating, who you might date, and who you never would. She knows what you look like, and what you’re likely to wear.

The invites work like this: Once the theme of the event is decided, Wintour starts thinking about the committees. Getting on a committee is an honorary badge of fabulousness, at least as sized up by the unforgiving eye of Anna Wintour. “Of course it’s a privilege,” says Lauren Davis, one of this year’s dance chairs. “It’s the most glamorous event of the year.”

Wintour doesn’t like the list of names to be a foregone conclusion. In order to keep things vital, she makes changes. If you’ve got a new movie, a new album, or you’re starring on Broadway, you just may make the cut. If you’re a longtime patron of Chanel with a closet full of six-figure suits, you’re also probably in. Probably.

The benefit committee is not so much a list of who will be at the party as a name-check of who’s really popular in America. It includes everyone from Katie Couric and Madonna to Harvey Weinstein and Renée Zellweger. Oprah Winfrey’s name shows up, as does Diana Taylor’s. Drew Barrymore is on the list, and so are the Clintons and a couple formally listed as TT.SS.HH. the Prince and Princess D’Arenberg.

Vogue staffers begin compiling their celebrity wish lists in September. The lists then go to Wintour, who delivers the final yes or no. Vogue then invites the celebrities, and farms them out either to their own tables or to the tables of the corporate guests, most of whom are big advertisers in Vogue.

With a reluctant celebrity, Anna herself will put in a few calls. And who can say no?

“A designer will call and say, ‘We’re looking for X, Y, Z to fill out the table,’ ” says Wolkoff. “If it’s someone that’s appropriate for that table, we will first call the agency and say, ‘How do you feel about this?’ and then the celebrity will be asked.”

Tables cost up to $150,000—and they’re sold out.

Designers have to do their own wrangling, too. Particularly hot this year, for example, is L’Wren Scott, a previously B-list L.A. stylist who’s quite publicly become the lover of Mick Jagger. Designers are frenzied about inviting her, even though she’s being coy about whether she’ll bring a date.

Some designers are lucky enough to have established “close personal” best-friendships (or advertising deals) with certain stars, so whom they’ll bring is a foregone conclusion. Marc Jacobs has often brought Sofia Coppola. (This year, Coppola is shooting and can’t get away. His substitute? Marilyn Manson.)

Up for grabs are Richard Gere, Naomi Watts, Usher, and Tom Brady of the New England Patriots—who is not terribly likely to be in high demand. Teen Vogue is said to have pulled in a particularly glittering bunch that includes Jake Gyllenhaal, Li’l Kim, Lindsay Lohan, Claire Danes, Nicole Richie, and both Olsens.

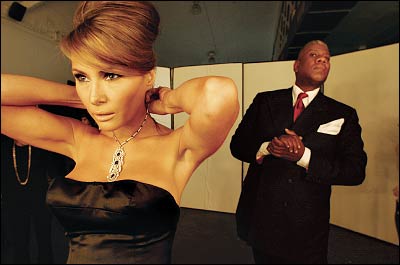

Then comes the hard part: the seating. Wolkoff considers not only who each guest is next to but also who is behind him or her. Last year, for example, Wolkoff dealt with the fact that Jennifer Lopez and Mark Anthony were not yet “out” as a couple by placing them back-to-back so they could whisper over their shoulders.

Another consideration is the sight line. A Vogue advertiser with a B-lister at his table might nevertheless have a carefully considered and unobstructed view of Nicole Kidman’s clavicle. “I mean, I didn’t know any of this before Anna taught me,” Wolkoff says.

At press time, it looked like Anna Wintour’s table might seat Tom Ford and Miuccia Prada, Andre 3000, and Jimmy Fallon. Liev Schreiber could compliment Natasha Richardson on her Vera Wang dress, while her husband, Liam Neeson, makes conversation with Vogue contributor Miranda Brooks.

“People always think the other table is better,” Karl Lagerfeld says. “I am pretentious: I like trendy editors, the girls of the moment, but I want to sit with my friends.” The friends are said to be Ingrid Sischy and Sandy Brant, Stephen Gan, Hedi Slimane, and Nicole Kidman, the current face of Chanel and the celebrity chair of the event. He’ll also have several terribly hot models, whom he is pleased to describe as “new—but very good!—friends.”

Vogue also uses the party to validate young designers, some of whom have start-up costs less than the price of a table. Zac Posen, for instance, will likely be sandwiched between backer P. Diddy and cheerleader André Leon Talley at a Vogue-sponsored table. “I’d better be in Mongolia if I was invited and didn’t go,” says Peter Som, the young designer. This year he doesn’t have a celebrity to dress, just a photogenic Vogue editor named Meredith Melling Burke.

Jack McCullough and Lazaro Hernandez, the moody-eyed pretty boys behind Proenza Schouler, get prime seating—they’re photogenic and talented—with Vogue fashion features director Sally Singer and Jennifer Connelly. Last year, McCullough and Hernandez dressed Marisa Tomei; this year, they’re still waiting for promises.

André Leon Talley says, “You cannot lobby for your seat. I can if I want.”

It’s a work in progress, that seating chart. Wolkoff keeps a calligrapher by her side the day of the event. It’s inevitable that changes will have to be made.

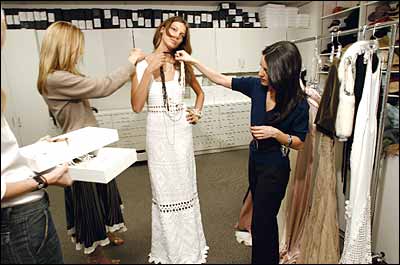

While Wolkoff worries about where people are sitting, the guests are worrying about what they’re wearing. And wardrobe decisions, too, are down to the wire. Some are confirmable: Katie Holmes, for example, is newly besotted with Carolina Herrera and has already been fitted, alongside socialites Jennifer Creel, Heather Mnuchin, and Wolkoff herself, by Herrera design director Hervé Pierre in “Chanel-inspired” one-of-a-kind dresses. Rachel Weisz and Bridget Moynahan have been making some very convincing noises over at Valentino, and Naomi Watts had definitely been sighted at Calvin Klein. Narciso Rodriguez has worked up something special for his loyal client Jessica Seinfeld, and Connelly is rumored to be working on something with Balenciaga.

And, of course, there’s Chanel: Lagerfeld adapted one of Coco Chanel’s best dresses from the twenties for Wintour, and Kidman will wear current season. Vanessa Paradis is wearing regular old Chanel, while Selma Blair found a piece of haute couture in the archives that appealed. The young dance chairs were each invited to pick a favorite. Lauren Davis had one in mind from a few years back that she will accessorize with ropes of black Tahitian pearls from Chanel’s fine-jewelry shop on Madison Avenue.

For a young designer, the ball can have a kind of Cinderella effect—come as a commoner, leave as a princess. This is what happened to Behnaz Sarafpour, who is a particular favorite of Wintour’s. When she first attended two years ago, she dressed Selma Blair in a signature gold-and-white tulle dress. It turned out to be one of the evening’s most photographed dresses. “She stepped out of the car, literally one foot out of the limo, and I could hear the photographers screaming like it was the Super Bowl or something,” Sarafpour recalls. “I’ve never witnessed anything like that in my life.” It took them half an hour just to make it up the museum steps (Sarafpour timed it). She got calls about the dress for a year, and it eventually wound up in an exhibit on Hollywood glamour at FIT.

To facilitate such moments, Talley serves as a kind of fashion consigliere. This year he helped fit Fifth Avenue socialite Patricia Altschul into a Chanel from the exclusive Los Angeles vintage shop Lily et Cie. “It’s the most extraordinary, fabulous, incredible dress, from Karl Lagerfeld’s second collection, when he went to Chanel in 1983,” Talley says. “It cost a fortune, and Pat came to the Duke Diet & Fitness Center”—where Talley himself was a recent client (he lost 28 pounds)—“and she lost five pounds, and went back to California and tried the dress on, and it fits perfectly. She has gone to that length to be dressed properly for the evening.”

In his role as de facto host and style adviser, Talley accompanies Anna Wintour and her daughter, Bee, to fittings (Chanel for the senior; Rochas for the junior) and traditionally walks them up the steps at the Met. This year he reserved an Alexander McQueen gown for Melania Trump (Trump insists that she found the dress first, but why quibble?) and counseled Andre 3000. “Tom Ford suggested he call me, and I suggested to him a diamond bow tie, from Fred Leighton, with real diamonds from the twenties. I wanted to wear it, but I said I would let him wear it if he wanted to, because I have so much respect for his music.” (In the end, neither will be wearing that much bling. At least not around their necks.)

In the eyes of many at Vogue, the most dangerous of last year’s liaisons was with the riffraff that invaded after dinner. The dance, according to Wintour, had “lost its glamour.” Wolkoff translates: “People weren’t dressing.”

In the words of socialite Celerie Kemble, it was a real “ratfuck.” And when the unwashed flowed in (one guest had interpreted the “Dangerous Liaisons” theme to mean a giant, conical Vietnamese peasant hat), the famous and rich and beautiful called their limos and went home.

The solution—sometimes party planning is a lot like rocket science—was to pick the six richest, prettiest girls in New York and appoint them dance chairs. Choosing the six—a Trump, a Safra—was simple enough.

“They’re the girls!” says Wolkoff, shrugging. “They love fashion, they love events.”

And they each had a number of friends—under the age of 32—willing to shell out $400 a ticket. There’s even a waiting list.

“The only people who have said no are out of town,” says Lauren Davis. “My phone has been ringing off the hook. Everyone wants to know what to wear. I’m just saying something Chanel, or something fabulous.”

The party’s been happening since 1948, when the Costume Institute was founded at the Met. It was decided at its inception that the American fashion industry would be responsible not only for creating the institute but for producing its entire annual operating budget. Eleanor Lambert, the legendary publicist who died in 2003, started throwing the fund-raiser, and it was glamorous, if rather naff—the evening’s main entertainment was in the form of women from the fashion industry parading around the exhibit. The heat came with Diana Vreeland, whose first exhibit, on Balenciaga, was in 1973. Vreeland presided over the exhibitions—and parties—with her typical flair. One of her favorite methods was to pump gallons of appropriately themed perfume into the galleries. For an exhibit on Russian costume, it was ten gallons of Chanel Cuir de Russie. For a 1980 exhibit about China, it was Opium. Guests complained, but Vreeland insisted the scent was necessary, as it supplied a “languor” that was otherwise lacking.

The socialite Pat Buckley, a fund-raiser for the Costume Institute, was another guiding spirit—and she was concerned with saving money. “She was up there in the cherry picker hanging things herself,” remembers Aileen “Suzy” Mehle, the gossip columnist. “And she was always running around downtown, bragging that she got this or that for twelve cents.”

As Mehle explains, “Anna really is the one who got Hollywood involved.”

The party has taken place in various parts of the Met over the years. Wintour remembers 1995, when the dinner took place on the balcony, the dance in the great hall below. “We shook the pottery too much,” she explains. Wintour has also, in other years, hired scores of cadets from West Point to line the steps of the museum, or the Harlem Boys’ Choir to sing Christmas carols (the event used to take place in December).

This year, the dinner will be in the American Wing, where the façade of a bank lends the illusion of a backyard—the backyard of, say, Karl Lagerfeld’s personal château.

Wintour insisted the caterer travel to Paris for a tasting at The Ritz.

The event had mostly been designed by Robert Isabell since 1995, but the liaison had become stale. “Robert and I both said it was time for a change,” Wintour says. “We’d been doing it together for so long, it had become like reinventing the wheel.”

Enter David Monn. He’s been in business less than three years, but he came highly recommended.

“He seems to be someone who is happy to take some degree of direction,” Wintour says—high praise under the circumstances.

“For an event to really … take you, you must engage all five senses equally,” Monn says as he steers an enormous SUV toward the Lincoln Tunnel on the Jersey side. He’s just finished inspecting the 14,000 pounds of boxwood that will make up the bulk of the French garden he’ll construct at the Met, and he’s got a lot on his mind. “Imagine your body not having one of its senses intact. I mean …” His voice trails off at the horror. He’s already had to nix the idea of using a “party fogger” in the American Wing—“It’s supposed to be dusk! When you’re working with the Met, there are all these considerations. One bug gets in there …” Monn trails off again.

But happy Monn is. “For me, success had always been gauged by money,” Monn explains. “And I had very good luck making money. But I hated every day of my life—really did!

“I have some strong beliefs, and one of them is that if you’ve been given a semblance of intelligence and you’ve been blessed with a talent and you’re unhappy, you need to look in the mirror.”

Monn looked in the mirror, left the diamond business (more Zale’s than Cartier, truth be told), sold his ten-acre estate in Sharon, Connecticut, left his classic six on Fifth Avenue, and got into the party business.

“There are some people who work. I don’t work. At all. I’ve always been all about creating the fantasy, and that’s my gift. Seeing the magic happen.”

Monn put together an elaborate proposal for Wintour and Wolkoff. His original idea was all about peonies or roses. He prepared a special cake for Wintour: angel food filled with a rose jam he’d made himself. “Euphoric,” he says. “She ate the cake!”

“I wouldn’t go that far,” says Wolkoff, laughing.

Regardless, she liked the proposal but not the roses.

Chanel has a particularly close and loyal relationship, after all, with camellias and gardenias. “But no one has ever done this with a gardenia before,” says Monn. He figured he’d need 7,000 perfect specimens: 3,000 for the entrance hall, and 100 centerpieces of at least 40 each.

After pleading with gardeners all over the country to part with branches from their gardenia trees—“which will never happen, because they’re, like, the golden chicken”—Monn found one farm in California and another in Florida. But nothing dies faster than a gardenia.

So in February, Monn began what he calls the Gardenia Death Watch. Because a gardenia begins to brown from the moment it’s picked, Monn had to test the life span of each flower by enacting a full test run of a gardenia’s journey to New York via FedEx.

What he learned was this: If the flowers are picked Saturday afternoon and sent at once, by chartered cargo jet, they’ll make it till 11:30 Monday night, wilting only as the Town Cars begin to line Fifth Avenue.

He can’t even discuss the possibility of a rainstorm, a foggy evening, a delayed flight. “For Anna Wintour, there is no plan B. There is always only a plan A.

“It’s going to smell amazing,” he says.

7,000 fresh gardenias arrive Sunday via chartered, refrigerated jets.

The chairs were another challenge. Monn wanted the slatted green type that cluster by the fountains in the Luxembourg Gardens. “We tried everywhere. And then there I was in a taxi outside of Bryant Park and I said, ‘Oh my God. My chairs.’ ”

Monn arranged to borrow 850 of them for the evening, and quickly set about measuring each so that their unforgiving iron seats could be fitted with moss-green cushions. The only caveat is that they will be available for pickup at 4 A.M. on Monday, May 2, and must be returned by 4 A.M. the next day.

As for the tables themselves: “What we’ve done is an overlay of Belgian linen,” says Monn. “It’s really, really, really beautiful. Hemstitched. Exquisite. The nicest fabric in the world.” The idea that such a fabric would be creased is just unbearable. “We’ve built a pressing table, and the linens will be starched and pressed right in the Temple of Dendur, and they will be carried by two people and placed right on the table.” When Wolkoff travels to Monn’s studio two weeks before the event, she loves what she sees: An army of men are stapling branches of thick English boxwood onto benches, and storing them efficiently in three refrigerated trucks parked in the drive.

The wire topiaries are next, and Monn proudly holds one atop a platform to show off his work.

“I love it,” says Wolkoff, but a flash of panic crosses her face.

The sight line!

Within minutes she’s dialing Wintour’s office. “Is she there?”

After a 30-second conversation, Wolkoff is photographing the orb with her camera phone.

“David, can you, like, sit there? Behind it? Like you’re sitting at a table?”

Monn squats. It looks like he’s been caught going to the bathroom behind a shed.

“You can’t show this to Anna Wintour!”

The food at a party like this is like the lining of a pocket—no one pays any attention to it, which doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be just so. “I wanted the menu to come from the Ritz,” Wintour explains, “because Mademoiselle Chanel lived there for so long.”Wintour requested that the Ritz work up some sample menus, and then, in February, put Sean Driscoll, an owner of Glorious Food Catering, on a flight to Paris. Back in New York, he prepared a version of what he’d eaten at the Ritz. “Chanel was a meat-and-potatoes gal,” Driscoll says. But he wanted the menu to be fairly light in honor of spring. When Wintour came to his office for a tasting, she wasn’t happy. “It was delicious,” Driscoll says, “but ‘French country’ rather than ‘French elegant.’ ”

In Wintour’s opinion, the colors weren’t quite right. “Instead of haricots verts, we’re going for a mélange,” Driscoll says. “You have to put your ego aside, because everyone says exactly what’s on her mind and Vogue leads everything. Then, the people from Chanel and the Met. Three alpha people.”

In the end, it’s lamb, vegetables, and a dark-chocolate cake topped with a white-chocolate camellia—Chanel’s other signature flower. “Anna said, ‘Fabulous,’ ” Driscoll says.

Karl Lagerfeld is known for his outspoken declaratives when it comes to fashion, so the most nerve-racking thing for Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, the curators, was approaching the designer with their idea. “He’d always said, very clearly, that he wouldn’t want his things in an exhibition, that runway to retrospective is not his idea of fashion,” Koda says. Part of what smoothed Lagerfeld’s red carpet to the Costume Institute was that Olivier Saillard, the stylist who’s been wowing Paris with his fashion exhibitions at the Louvre—he’s just put one together on Yohji Yamamoto—should design the show. He’s worked quite a lot with Chanel. And, says Koda of Saillard, “He’s a poet.”

And besides, Lagerfeld is a superhero on a massive scale. The lines outside H&M last fall when he designed a cheap collection were a serious turn-on for the Met. As Lagerfeld puts it, “Can you think of another brand that is more popular?” He didn’t think so.

“What we wanted to do was to present the modernism of Chanel as something that is a living legacy,” Koda explains. “So many of Coco Chanel’s ideas have become the lingua franca of contemporary dress that they’re invisible to us at this point. The way that we wanted to establish that is to draw the affinity of the original Coco to avant-gardist architecture of that time.” They settled on a ratio of two Cocos for every Karl.

Once Saillard got to the museum, he proposed two ideas. Koda calls the winning design Chanel City: a gridded plan of interlocking square modules. “He’s looking at Le Corbusier, he’s looking at the White City,” says Koda, “all of which Karl encouraged us to think about.”

Where Lagerfeld did get extremely involved was with the catalogue. “At ‘Dangerous Liaisons,’ he was upset that there wasn’t any color to the mannequins, so at one meeting he took out some colored pencils and did a sketch on a photograph of a thirties dress,” Koda says. “Everybody got very excited.”

“It was a nightmare,” says Lagerfeld of the work he did on the catalogue. “I had to get up at four in the morning for weeks to do this. This technique has never been done before. It is something only I can do, and it gives a new idea to old clothes.”

At an 8 A.M. meeting on April 21—in fact, the regular 8 A.M. meetings, given Wintour hyperefficiency, are often over by 8 A.M.—Anna Wintour sat flanked by Emily Rafferty and Wolkoff, the three of them answering questions from the various representatives of Monn, Driscoll, and Chanel in rapid-fire succession. There’s some concern that two trumpets—used to signal the end of cocktail hour and the beginning of dinner—won’t be enough.

“Well, then let’s have four,” says Wintour.

Next?

“There’s some sort of nuclear protest in the park on Sunday,” says David Monn. “It’s blocking my access to the loading dock.”

“Well, then, we’ll get you in on Saturday,” says Wintour.

“We can put the carpet in the Temple of Dendur,” says Rafferty.

“Ooh,” says Monn. “You’re giving me chills.”

Additional reporting by Sarah Bernard (food), Melena Z. Ryzik (fashion), and Alexandra Wolfe (society).