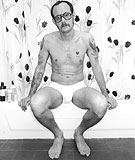

Terry Richardson is a 36-year-old with a handlebar mustache, long sideburns, and a collection of odd tattoos, including one on his belly that says t-bone and one on his heart that reads ssa. He’s tall and a bit bandy, and he’s likely to be wearing faded jeans, Converse sneakers, and giant, slightly tinted aviator glasses. He’s seventies-looking, not in a retro hipster way but in a Starsky & Hutch way, with a touch of Burt Reynolds thrown in for good measure. He’s charismatic and famously attractive to women, despite his somewhat cartoonish demeanor. And much of the time, he carries a small snapshot camera with him, just like one you might take on holiday to record your adventures, which is more or less what he does for a living.

While most fashion photographers travel with a phalanx of good-looking young assistants wielding lights and oversized lenses, tripods, film bags, and reflectors, Richardson arrives on location with a couple of instant cameras, one in each hand, and nothing else. He doesn’t design the lighting, doesn’t plan his shoots, forgoes Polaroids, and never choreographs poses. He likes to work with little fuss and no entourage. And yet, in the last few years he has shot campaigns for Evian, Eres, H&M, Tommy Hilfiger, Anna Molinari, A|X, Sisley, and now – one of the biggest scores in the fashion world – the fall campaign for Gucci.

“You know how cameras are supposed to symbolize sexual power?” asks the creative director Nikko Amandonico, who has worked with Richardson since 1998 on the Sisley campaigns. “Well, Terry is a big man with a tiny camera. He looks funny. He makes jokes with his camera, and that’s how he gets the shots.”

Richardson has wielded his point-and-shoot on Faye Dunaway, Catherine Deneuve, Sharon Stone, the Spice Girls, and a great many famous models. His work has been exhibited in galleries in London, Paris, and New York, and he has been published in magazines as varied as French Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, i-D, Vibe, The Face, and the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue.

“It’s the most amazing feeling when you are shooting something that you know is good: It’s like great sex.”

“At the beginning,” Richardson says, “people laughed at me because I was using snappies. Sometimes, a celebrity would look at my camera and go, ‘Oh, I’ve got one of those.’ I’d feel like handing it to them and saying, ‘Well, you take the pictures then.’ But I like using snapshot cameras because they’re idiot-proof. I have bad eyesight, and I’m no good at focusing big cameras.

“Anyway,” he continues, becoming more animated, “you can’t give your photograph soul with technique. I want my photos to be fresh and urgent. A good photograph should be a call to arms. It should say, ‘Fucking now. The time is ripe. Come on.’ “

These days Richardson is enjoying what many in the fashion world call a moment. Designers and stylists are entranced by the way he gives a glossy fashion spread a palpable – and somewhat coarse – sexual punch. “He’s a modern Helmut Newton,” raves Emmanuelle Alt, the fashion director of French Vogue.

“We’d run the gamut of slick, finished photography,” says Douglas Lloyd, the art director behind the Gucci campaigns, about the decision to use Richardson. “We wanted a rawer energy and more sex appeal, and that’s what you find in Terry’s work.”

“Terry is very much about sex,” says Gucci designer Tom Ford, “but what I love about his work is that his pictures jump off the page at you.” In fact, Richardson has already been confirmed as the photographer of choice to shoot the next go-round for Gucci, which will feature Ford’s spring 2002 collection.

This is what happened the day in June when Richardson received the news:

He spent the morning in his studio on the Bowery – a long space with a white shag pile carpet at one end, a workstation at the other, and a full-length mirror in between – catching up on phone calls and editing prints with his associate, Seth Goldfarb. Benedikt Taschen, the iconoclastic art-book publisher, was in touch about the possibility of doing a book. Harper’s Bazaar called about booking him to shoot a fashion story for Glenda Bailey’s first official issue. Then Tom Ford called.

In the afternoon, a band named the Centuries came over to the loft. They were wearing gold and silver lamé outfits, and Richardson photographed them as part of a series he is doing for the French magazine Self Service. The early part of the evening he spent with Lenny Kravitz, discussing the next day’s shoot, when Richardson would photograph Kravitz for his new record cover. Then he went to Sophie Dahl’s rooftop party. At the party, a young stylist asked him if he was the son of Bob Richardson, the renowned sixties-era fashion photographer. “Yep,” Richardson said, biting into a piece of mozzarella, “son of Bob.”

“How is Bob?” asked the stylist. “He’s well,” said Terry, enjoying his supper. “Still working. Still wakes up with a hard-on every day. Pretty good for 74 years old.” He demonstrated what he meant with a breadstick, took a snapshot of someone with his Contax, then told a story about a curious wet dream he had had only the night before.

Two days later, I watched as he packed his cameras and his suitcase for a trip to Paris, where he would visit his girlfriend, Camille Bidault-Waddington (a stylist who was named one of the world’s most fashionable women by Harper’s Bazaar), and shoot his next project, a couture story for French Vogue, with the model Angela Lindvall. Not too shabby, I remarked. “I know,” he said, grinning. “I’ll be like, ’Hello. Hello! Only me. Bonjour!’ “

“I don’t think Terry can believe his luck,” says the British stylist Cathy Kasterine. “A lot of photographers become frustrated once they’ve shot a few big campaigns and done their fair share of fashion stories. They don’t know what to say about fashion anymore. But not Terry. Every photograph for him is an adventure.” She starts to laugh.

“Sorry,” she says, “I was just thinking of how he looked when we first worked together. It was during his American-professor phase; he was wearing huge corduroy trousers and an English tweed jacket. This was in the bowels of Florida, at a nudist camp, where we were shooting an accessories story for Nova magazine. But that’s Terry. He makes you laugh; his photographs make you laugh.”

Still, much of the work Richardson is famous for is provocative and confrontational: a close-up of Richardson performing cunnilingus; a nude portrait of a bruised young woman crying on his bed; a close-up crotch shot of a woman wearing pink polyester underpants. One of his early assignments, a startling advertising campaign for the British designer Katherine Hamnett, captured a young woman staring at the camera with a frank, unashamed look. Her legs are open, showing a profusion of pubic hair. The photographs, after causing a stir in Britain, where they were published, provided Richardson with his first big break and foreshadowed the controversial “kiddie porn” Calvin Klein campaign.

As disturbing as some of his images can be, Richardson himself seems to generate general goodwill from everyone he works with, from corporate giants who entrust him with their commercial campaigns to notoriously fickle editors-in-chief. “You can be afraid of Terry and his work if you look at the stuff he does privately,” says Alt. “As a woman, I found those pictures really scary. But I think he can approach chic very easily. And he is very sweet and charming – he’s very fun to work with.”

But how, the industry wondered, would his informal snappy style sit with the Gucci team – Douglas Lloyd, Tom Ford, stylist (and recently appointed French Vogue editor) Carine Roitfeld, hairdresser-to-the-stars Orlando Pita, and makeup artist Tom Pecheux? The Gucci campaigns of the recent past had all been famously polished: Mario Testino’s sleek and perfectly accessorized beauties, Alexei Hay’s yoga-in-stilettos desert series, and the postmodern Marilyn-inspired Kate Moss, all creamy and bleached, by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin.

The initial reports weren’t positive. Fashion-world sources said Tom Ford visited Richardson on-set, hated what he saw, stormed off, and cut the shoot from six days to four. One or two models had been sent home early; others, the story went, had been made to cry.

“No shoot is without its process,” says Lloyd. “Terry hadn’t worked with the Gucci team before, so it took a while for him to develop a shorthand with them.”

Richardson admits that it was a struggle at first. He wasn’t getting good work done in the studio, so instead he took a small team back to his hotel room. He began simply messing about with his cameras, using the models and a bit of available space between the door and the bed. The result is arresting, simple, and direct: two girls and a guy, photographed singly and together, in the corner of an anonymous, cheaply carpeted, white-walled room. Something is either about to happen or has already happened – and that something is clearly sex.

“Terry was just like, ‘Okay, this is the campaign.’ I don’t know which images he shot where, with what cameras,” says Lloyd, laughing, “but Tom and I were thrilled with the results. It’s rare that we reconfirm a photographer this early, but we booked Terry to shoot the next campaign before these ads even broke.”

“He strongly believes that if you’re lucky enough to have a babe like Frankie Rayder in a black bikini in front of you, surely you’re going to encourage her to pull her swimsuit down”

The Gucci shoot is a good case study of the Richardson technique. Almost every shot poses the question How did he get that? “You have to take a risk,” Richardson says, simply. “That’s how you get something beautiful. It’s the most amazing feeling when you are shooting something that you know is good: It’s like great sex.”

And when it’s not good? “Well,” he says, “sometimes you have to do a little bit of cheerleading. But often things just happen. People like to perform in front of the camera.” He stops and listens to himself. “Especially if I’m in my Speedo,” he says, unable to resist.

Unexpectedly, I discover for myself how persuasive he can be. One evening, scheduled to look over some of Richardson’s early work with him, I arrive at his loft late, my face freshly swollen and blue from a bicycle accident. He makes me an ice pack and shows me the large scar above his nose, the result of a fight whose outcome was decided with a broken bottle. Of course, he says, he has to take a quick photo of my ghoulish face. Of course, I respond, anticipating that he’ll take one or two snapshots of me and my bruises in front of his white wall.

He begins by shooting a lot quickly, reloading film in one camera while snapping with another. He darts about, often sticking himself in the frame next to me. He doesn’t issue instructions as much as express enthusiasm – and not the yeah, baby sort. “God, I love taking pictures,” he says as he begins to find a line of energy between us. I am usually awkward in front of the camera, and I am self-conscious about my body, even on a good day, but within five minutes of the first frame, I’ve taken my top off. Why? Because he suggests it (“I love women’s bodies,” he says to me later, as in, Duh, well, of course) and because, amazingly for me, I feel comfortable. It’s like we’re in cahoots, spoofing what has gone on for years between photographers and their prey. And so, for whatever reason – Terry being Terry – he’s created yet another series of images that might well make you wonder how he got a bruised woman, clearly not a model, to take her clothes off against a white wall.

In one sense, Terry Richardson was born to be a photographer. His mother, Annie Lomax, worked for years as a stylist, and his father’s work in the late sixties and early seventies was as important as Richard Avedon’s and Helmut Newton’s in terms of changing fashion photography. The elder Richardson’s photographs hinted at narratives in which the models became characters, and the viewer – cast as a voyeur – was used to complete the story. Although Terry’s work does not look like his father’s more iconic images (Bob’s photographs are a lesson in composition, whereas Terry’s work celebrates the accidental), they share a preoccupation with documenting their own experiences. “I don’t know anything about fashion,” Bob Richardson tells me when I track him down in Los Angeles by telephone. “I just liked taking photographs of people and situations,” he continues, being deliberately deflationary.

And yet he and Lomax led a pointedly fashionable life for a time, traveling between Paris and New York and being part of that small circle of people who didn’t just dabble in sixties grooviness but played an important role in creating it. The marriage fell apart when Bob Richardson, then 41, began an intense four-year love affair with a 17-year-old Anjelica Huston.

“Anjelica was cool. She was like an older sister,” says Terry, when I ask him about his early childhood. “It was a funny time. I mostly stayed with my mom. I remember as a little kid looking out onto the terrace of our Jane Street apartment and seeing her making out with Kris Kristofferson.” But their life wasn’t jet-set for very long. After a stint in the West Village, Lomax moved to Woodstock, married a musician, relocated to Los Angeles, and finally settled in Ojai, California. The last move was triggered by a serious car accident she had in L.A., on the way to pick up her young son from one of his twice-weekly sessions with a therapist. “I was always getting into fights and being thrown out of school,” explains Richardson. He pauses. “It was quite heavy,” he says, referring to his mother’s accident. “She was in a coma for three weeks, plus shortly after that my stepdad’s record deal started to fall apart. Basically, our life became food stamps and welfare all of a sudden.”

Among the glossy magazines on Richardson’s coffee table is a mock-up of a book with the title Premature Ejaculation. It is full of photographs Richardson took when he was a teenager in Ojai. “My mom gave me a snapshot camera, and I took pictures for the fun of it,” he explains. “I lived on Signal Street, and my best friend and I started a gang called the Signal Street Alcoholics” – hence the ssa tattoo. “My mom would come home and there would be twenty kids smoking pot and drinking and screwing. I was selling weed and playing in a rock band. I took the pictures goofing around. They’re punk-rock snapshots. They look like the stuff I do now,” he says proudly.

The photographs are much quieter than they perhaps sound, and although they have been taken with a steady hand, there is no trace of a show-off behind them. They are affecting images of kids hanging out, making out, getting high, and lying around. Most of the people in the photographs, Richardson tells me, are now dead from drugs and self-destruction.

“No one encouraged me to continue taking pictures. No one ever said to keep doing it,” Richardson says without bitterness, “and so I stopped.” He moved to Hollywood, worked as a busboy in an English pub, and played bass guitar.

Meanwhile, his father – whose own career had long since unraveled, ending in a battle with drug addiction, a period of time living on the streets, and struggles with schizophrenia – had moved to San Francisco and found work in telemarketing. Tired of L.A., Terry joined Bob and began to take photographs again. “I had done some photographic assisting in L.A. to make some money,” he remembers, “and I thought, ‘Fuck it. If these people can make a living doing it, so can I.’ So I began taking pictures and getting a portfolio together. I would sit with my dad and edit film and drink red wine with some music on. My dad taught me cool things – like that you should always have a flashlight, extra batteries, and a corkscrew in your camera bag. One day he said to me, ‘You should move to New York and become a fashion photographer.’ “

And so he did. Not only that, he met and married a successful fashion model, Nikki Uberti. They became cult figures in the East Village, appearing in underground movies and taking off and returning from road trips to Middle America. The combination of their adventures, much of which Richardson captured and exhibited, and Uberti’s gloriously unself-conscious approach to nudity, resulted in some of his most famous images.

“They were just pictures of her and of our friends and of our life,” Richardson says about their collaboration. The carefree times, however, didn’t last. The couple divorced in 1999, and later that year Uberti was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent chemotherapy and a mastectomy. She has since become active in helping create awareness about the disease. Richardson is still visibly emotional about their relationship and keeps his thoughts about it private.

“I always take pictures of everything in my life,” he says. “But I don’t change the way I shoot if I’m working for a magazine. Of course, someone has done the model’s hair, and, yes, you’re selling a product if you are working commercially, but that doesn’t mean the pictures aren’t personal. My mood affects every picture I take. Every time I photograph someone, whoever it is for, I’m trying to get them to expose something about themselves, but I’m also putting myself in the picture, too. You have to make yourself vulnerable in order to capture something about the subject. You don’t get it every time, but when you do” – Richardson pauses and shakes his head – “it’s beautiful. There’s nothing else like it.”

Richardson’s work – especially his earlier, grittier shots – has been labeled heroin chic, but the term is misleading. Richardson’s photographs are celebratory; they’re fun. He strongly believes that if you’re lucky enough to have a babe like Frankie Rayder walking into the sunset in kinky boots and a black Ursula Andress bikini in front of you, surely you’re going to encourage her to pull her swimsuit down a little.

When I ask him if he thinks of himself as a photographer or an artist, he laughs and says that he’s a rocktographer. Asked when his last creative moment was, he says, “An hour ago,” and issues a dirty laugh. “Who were you photographing?” I query. “I wasn’t,” he says, “I was by myself,” and there is a glint in his eye. “When was the last time you got away with bullshitting someone?” I continue. “Right now,” he says. “How often do you get away with it?” “Every day!” he replies with total pleasure. “Your fantasy?” I ask. “To direct a film,” he says. He’s already directed music videos for Death in Vegas, Primal Scream, and the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, all of which have firm cult followings. I ask him if the film will tell his story. “I guess,” he says. “Yeah. I mean, I can’t write a fucking postcard, but my dad says the thing to do is just to do it, so that’s what I’ll have to do. Just do it.” “Who would play you?” I ask. “Billy Crudup,” he replies without hesitation. Why him? He shrugs and takes a bite of his sandwich. “Because he’s cute and he’s got a mustache,” he says. “It’s as simple as that.”