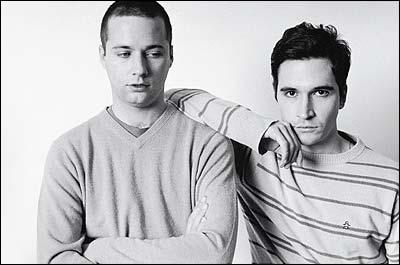

Photograph by Jenny Gage and Tom Betterton

When Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, the designers behind Proenza Schouler, sat down to design their fall collection, which shows February 7 in a gallery space in West Chelsea, they had very different things on their minds.

“In terms of feeling, Lazaro’s kind of feeling this Joseph Beuys–y, really organic kind of natural-fabric thing,” says McCollough.

“Easy,” says Hernandez.

“Easy but masculine,” adds McCollough. “And I was feeling this really kind of, like, hard, not industrial but artificial, kind of like black-and-white, primary-color kind of poppy thing. Like Calder mobiles. Kind of like primary colors mixed with brasses and metals.”

“Our stuff is always kind of, like, art” (Hernandez).

“We’re inspired by art. Even a little bit of, like, Pop Art–y stuff” (McCollough).

Hernandez and McCollough are both 26. They have matching speech patterns, verbal tics, and tattoos (a single dark star that hides behind their left ears). They are also Proenza Schouler, arguably the most popular label to come out of New York since Narciso Rodriguez.

They met at Parsons as juniors. Both were transplants—McCollough had started out as a glassblower, Hernandez was in med school—but they were instantly drawn to each other. They had to get special permission to do their thesis as a team. “They had such incredible synergy,” says Tim Gunn, the head of the fashion department at Parsons who okayed the union. “During their junior year, it became really clear that they shared a vision and a philosophy.”

The thesis collection they produced attracted Julie Gilhart, the fashion director at Barneys New York. She bought the whole thing and rolled it right onto the sales floor. It was a hit, and within months the pair had found a backer (a German guy who remains anonymous). They’re a real fashion fairy tale—it hasn’t hurt their case that they are both incredibly cute and artfully styled, and that there are two of them. What is it about pairs that is just so appealing? The fashion world is cruel and fickle, but it hasn’t been to these boys. There hasn’t been a bad review, an unflattering photograph. No one grand and glamorous has dropped them—yet. There is constant gossip about the state of their romantic life. They were, and now they’re not, or at least they are no longer living together—there are separate apartments and separate dogs. Regardless of the state of their love affair, their creative success is so dependent on each other that to contemplate a split would be insane.

“One of us might be feeling long when the other one is feeling short. So then we’re just, like, ‘Let’s do both.’ ”

Collaboration in the fashion world is not without precedent. Rarely is “Dolce” mentioned without “Gabbana,” “Badgley” without “Mischka.” It can be hard to know where the contribution of one ends and the other begins: “Although Lazaro is the more gregarious one, Jack has a stronger business sense,” says Gunn. “But it’s not like they were doing their things and then found each other. Proenza Schouler is the collaboration. Neither one of them would have achieved it alone.”

It should come as no surprise that Parsons students are lining up to collaborate, that McCollough and Hernandez’s baby-faced intern, on leave from the London fashion school Central Saint Martins, has already decided what she wants to do next: “A line,” she says, “with my best friend.”

But how does the collaboration actually work?

A few weeks after their show (usually they take a vacation to recharge), the designers sit down together and figure out what they’re feeling—if they’re feeling “arty,” well, then, which art?—and figure out how to meld these things.

“Last season, Jack and I went to the Seychelles,” says Hernandez. “And it was even before that that Jack was feeling kind of Hawaiian prints and surfy and kind of colorful. And then I was sort of feeling kind of like this proper, neoconservative Jackie O.–y kind of stuff. I knew that that was dorky, but that was why I liked it. But then Jack was still into this whole sort of surfy thing. So we sort of, like, brought those two worlds together. And then we were in Africa, in the Seychelles, and that was kind of an inspiration. But it was those two worlds coming together. If either of us had gone independently in our own direction without having the other side …”

McCollough: “It would’ve been too one thing. So we ended up having quilted Hawaiian prints but with kind of, like, these very early-sixties shapes, you know?”

Hernandez: “We were thinking how cool it would be to have a really proper and conservative suit but having the top be one print, and the bottom some crazy other print, and the prints don’t match, so it’s kind of like she’s really sort of proper but a little nuts. Which is kind of cool. Which gives it the subversive twist that we love. So the people that don’t get it, that’s fine, and the cool girls do get it, and buy it!”

So if McCollough’s feeling tropical and Hernandez buttoned-up, then how about a pattern of grand hibiscus imprinted on a roomy trench? Then comes the research phase: Both spend a bunch of time at the Condé Nast library amassing photographs, drawings, whatever seems attractive now. Whenever one designer finds something, he makes two copies, and diligently pastes it in both his and his partner’s inspiration book. (This season, there’s quite a bit of sturdy and structured lingerie, fifties-style. There are also pictures of Madonna’s conical bra by Jean Paul Gaultier for her “Blond Ambition” tour.) Then they sketch, separately, for about two weeks. Then they inspect each other’s sketches (they swear there are amazing similarities even at this phase, that they gravitate toward the same things in the inspiration books), comment, and start figuring out which sketches to produce and sample. And here’s where it can get tricky.

Hernandez: “One of us might be feeling long when the other one is feeling short. So then we’re just, like, ‘Let’s do both.’ Like, miniskirts with long coats over it. It’s more expensive to have two people ’cause I’m like, ‘I want that dress in white,’ and Jack’s like, ‘No, white’s gross, let’s do it in black.’ And then I say, ‘Oh, we did black last season,’ so then it’s just like, ‘Okay. Let’s sample it in both.’ At the end of the day, we’ll just have to see what’s cuter.”

See Proenza Schouler’s collections.

This season, the fusion of “Beuys-y” and Calder is taking the shape of soft evening dresses and man-tailored suits sexed up with the heavily boned lingerie that has become a signature for the label—usually in the form of tightly fitted bustiers. There are bustiers this time, of course, but now there are also girdles sticking right up out of a pair of low-slung trousers and fastened on top of a fitted blazer. The boys are working in their Chinatown studio with their fit model Soos, a lanky redhead who looks far more like a fashion illustration (all sharp jutting angles and irrationally long limbs) than an actual person, and two seamstresses. The designers are dressed almost identically, in well-worn corduroy Levi’s and T-shirts. McCollough’s arms are covered with tattoos; Hernandez is wearing a cardigan, but the overall look is the same: a distressed preppy who’s discovered the East Village.

The designers circle Soos: First McCollough is in front, then Hernandez. When McCollough concentrates, he bites his nails; Hernandez furrows his brow and purses his lips. When they do meet at, say, Soos’s side, McCollough, who has a cold, might rest his head, for a second, on Hernandez’s shoulder.

Mostly, they affirm each other.

“Is it weird here?” McCollough wants to know.

“It’s cute here,” Hernandez says, waving his hand across the butt.

“You know what would be good? Suspenders,” says McCollough.

Hernandez makes a face; McCollough agrees immediately.

“Yeah, I guess the adjustment things would be hard.”

And how far up should the girdle go? The sewer wants to know.

“It’s perfect,” they say. The simultaneity of the proclamation is eerie.

It’s a bit of a fashion parlor game to pronounce which of these boys is the talent, which the hustler. But considering how young they were when they met, it’s a mistake to say that their strong aesthetic is more the product of one’s mind than the other’s: To see such polish and signature come out of such young designers suggests that maybe it really is the fusion of the two perspectives that makes it so grown-up. McCollough says he’s the dreamer of the two, the more painterly, the more fantastical. Hernandez is more concerned with wearability. Or at least it was that way when they joined up, but they’ve been working together so long that neither really developed an independent philosophy. They’re still figuring out who is better at what. “He was really painterly, really fine-arty,” says Hernandez. “That was really attractive to me. When I first met Jack, he was doing all this crazy Japanese-y thing that was very costume-y. I was very ready-to-wear, and so to me it was really fascinating. He brought this level of imagination to things. He was definitely way fantastic.”

(Neither is the business brawn—for that they have Shirley Cook, 25, whom they met through a mutual friend. It’s Shirley’s job to explain to the factories that no, they don’t need all that fabric, and who told the factory to take orders from Lazaro, anyway?)

It varies from season to season who does what. “One season I’ll do all the dresses and he’ll do all the coats,” says McCollough. “And then we’ll be like, ‘Oh, wow, I guess I’m good at dresses and Lazaro’s good at coats.’ And then we’ll totally shift around.”

They do every single fitting together—both pinching, folding, puzzling together over just how short is “like, vulgar.”

Maybe, but they’re both looking forward to living apart.

“Jack’s been, like, my best friend for like five years,” says Hernandez. “When we first met, I was a teenager. I’ve obviously changed a lot, and what we’ve been through in the past five years has really been kind of crazy. He’s just like my best friend, but we’ve, like, learned how to be adults together. We had not one responsibility in the world four years ago, and now we have all the responsibility in the world and we’ve sort of done it together. So he’s taught me how to be an adult, I guess.”

“So sweet!” says McCollough. “Sometimes I’m like, ‘Fuck you! I’m starting my own company, I don’t want to deal with you.’ ”

“And sometimes I’m like, ‘Fuck you! I don’t want to make that black dress!’ ”

“We have our moments of nastiness.”

“As with anyone.”

“We always fight a lot right before the show.”

“When you’re a kid and you’re pissed off at school or something, you come home and take it out on your mom because you know that she’s just there.”

“It’s hard separating work from personal life,” says McCollough. “We’ll get into an argument about a button at work and then when we leave it’s like, ‘Don’t talk to me. I’m still mad at you about that button.’ ”