Though nothing like its neighbors, the house on East 63rd is surprisingly easy to miss from the street—deliberately so. Architect Paul Rudolph, intent on creating a retreat from city life, made sure his clients would live in what one critic referred to at the time as “a world of their own.” The brown-glass façade intentionally recedes from the eye. A successful disguise, the design nonetheless gives the house—built for real-estate lawyer Alexander Hirsch and his partner, Lewis Turner, in 1967—a mysterious, almost uninviting quality.

Luckily, countless New Yorkers would be undeterred by this. After Halston bought the house in 1974, it became a sort of hyperelegant confirmed-bachelor pad, and for fifteen years, the boldfaced walked brazenly in. They even gave the place a nickname, “101,” its street number. Normally they came for dinner, which, prepared by Halston’s live-in assistant, Mohammed Soumaya, usually consisted of caviar, a baked potato, and cocaine. “Often the potato course was passed over,” notes Halston biographer Steven Gaines. During a supposedly secret “drag party,” Steve Rubell wore one of Liza Minnelli’s dresses.

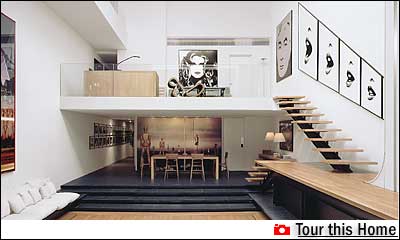

When you enter the townhouse today, it immediately introduces you to its starstruck heritage. In the long foyer, current owner Gunter Sachs, the Swiss millionaire and photographer, has hung 40 black-and-white Warhol photos of Halston’s crowd and other celebrities. Jacqueline Onassis stands alongside Bianca Jagger. A puffed-up Truman Capote hangs not far from a young Dustin Hoffman on his motorbike. The final image—set slightly apart, as by now the hallway has opened on a dining area—is a portrait of Minnelli. In a black dress, she lies on a concrete platform at the bottom of a staircase. Turning to the left, you see that it’s the same staircase in the living room. Naturally, Liza was here before you.

The house no longer bears Rudolph’s “haute minimalist” stamp, also embraced by Halston. After the designer moved in, he lured back the architect to make it more comfortable. There was only electric heating, and Halston inquired of Rudolph’s office whether anything could be done about his electricity bills, then over $3,000 a month. “Is this normal?” he asked. The carpeting was ubiquitous, and it was gray. As was the upholstery. And not just any gray. “Halston would look at hundreds of samples to make sure we got the shade right,” recalls Donald Luckenbill, who worked as project architect for Rudolph.

Sachs has pared the interior down but also splashed it with color—like his own lush photographs. The artist, who in 1966 cemented his credentials as a member of the European jet set by marrying Brigitte Bardot (they divorced in 1969), maintains multiple residences. In fact, he’s owned 27 to date. “I come here two or three times a year,” he says. “I wish it was more.” Working with designer Lars Bolander, Sachs replaced the gray carpeting with white oak floors.

But the bones stay the same. And when he is in residence, Sachs finds himself continually marveling at “the height of the salon.” Who wouldn’t be taken in by the three-story-high living room? It embodies the bold architectural strategy Rudolph was pursuing at the time. A generation younger than modernism’s originators, he was intent on advancing their ideas about opening up interiors to the outside and breaking down barriers of social and private space.

The plans, which were displayed prominently in the New York Times in 1967, show how the house pinwheels around the central atrium—to which each floor has dramatic entry and vantage points: a catwalk to a third-floor guest bedroom, a mezzanine that floats over the dining area. Compared with the vast salon, the other rooms feel sheltered, some with ceilings as low as seven feet. But Rudolph’s open design allows light to flow throughout, relieving any tightness.

As was his wont, the architect all but dared his clients to live on the edge on his architecture. He refused to put a railing on the catwalk, believing it would make the living room a less integral space. Instead, he called simply for a leather-covered rope. Lewis Turner suffered from vertigo and ventured across to the guest quarters only ten times in the seven years he and Hirsch lived in the house. Sachs had glass panels installed on it and the mezzanine, one of his few interventions.

The stairs Liza cozied up against have been left open, an inopportune gesture, perhaps, in a house that in its Halston years was home to so many who couldn’t be bothered to eat their potatoes—but a lovely one all the same. As Sachs says, “The whole concept” behind 101 was—and remains—“enormously avant-garde.”