It is not your typical late afternoon here in the living room of the Brooklyn homestead con der kinder. The usual parental bleating about going outside, getting some exercise, doing homework, walking the dog, etc., etc., has been temporarily suspended. The TV’s on, sure, but this time tuned to CNN. My two daughters, one teenager and one near teen, are transfixed, watching the Columbine massacre. Again and again they see footage of the students running from the besieged school, hands on their heads, bolting across the well-kept lawn. Over and over the stories of the library shootings are told, how Harris and Klebold, TEC-9 and shotguns in hand, canvassed the terrified students, demanding to know who believed in God and who did not. “There is no God,” one of them said, and fired, point-blank.

On it pours from the Hitachi, the soul-shredding thrum of crying students, grieving parents, congressmen calling for action and/or compassion, reporters filling time. But my daughters, who have so often claimed boredom in any circumstance, can’t get enough. They eat dinner in front of the set, fearful they will miss a single recap. In a tangential, contained way, it’s like when Kennedy was shot and another crop of teenagers listened to Chet Huntley and Walter Cronkite intone those same things about Oswald and Ruby a thousand times until they became ritual knowledge, mantras to be repeated and carried about for a lifetime.

All hell breaks loose in different ways, for different generations. Thirty-six years after the grassy knoll (21 past Jonestown), my daughters walk seemingly endless high-school hallways fraught with adolescent terrors real and imagined, and now the nightmare of Columbine belongs to them.

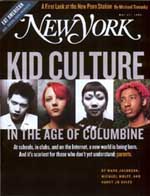

“I can’t believe it,” my older daughter says, black-shadowed eyes glued to the tube. As a goth partisan and ardent adherent to the Cobainian-Anne Rice necro-Goddesshead, her first reaction was to be pissed that the media creeps had assigned the Trench Coat Mafia to her chosen fashion bag. Soon, however, the repeated viewings of the dead and wounded reduced her to a numbed, stumped silence. Littleton, Colorado, might be some rich-kid suburb, a million psychic miles from hanging out on St. Marks Place, but to the extent that youth cements a bond, these students, victims and killers both, were my daughter’s People. And yet, knowing all she knows about the horrors of high-school personal politics (including the far-from-abnormal fantasies of leaving the place a smoking hole), the disaster remained a mystery, even to her.

So now we’re into blame. Affixing root causes. Outside of the sick kids who did the shooting, what elements of society can be held responsible for this climate of violence that, after numerous other similar incidents, has reached critical mass out there in Colorado? The usual suspects have long since been rounded up. Littleton swat teams may have frozen, but bow-tie-wearing millennialistas have been on the scene like a ball of heat. It is grim amusement to listen to corporate purveyors of the scuzzy pop culture (of which I am certainly one, being an occasional rewriter of movies full of needless death) mount defenses similar to the usual NRA fallback position: Just as guns don’t pull their own triggers, it’s not the foul TV shows and movies that kill but the people who watch them. Well, sure. Who are we to mess with the market, not to mention the First (and Second) Amendment. If video games in which the goal is to kill as many people as possible constitute an enhanced Coney Island shooting gallery, complete with portentous techno soundtrack, and this proves fatally seductive to a segment of the overly suggestible demographic, isn’t this just the chance we have to take to live in the Land of the Fee?

Business is business. Who knows what really went through the mind of Eric Harris as he rolled strikes in his 6:15 a.m. bowling class on the morning of the murders. But if the culture has so heavily invested in the empowerment of youth (and youthful spending) that kids have actually come to believe that, yeah, just like on any grown-up-devoid WB show, they are firmly in control and call the shots – is there anything to be done except let the impulsive, highly hormonal chips fall where they may? The latent Humberts among us might like those budding hard bodies on the tube, but there seems to be a cost in ceding the cultural landscape to the wrinkle-free. It was lies, all lies, but what ever happened to the days when Father Knew Best? Back then, as a zombie teen, I used to delight as Paladin, of Have Gun Will Travel, gunned his way through the West. But Paladin was a grown-up bounty killer, with world-weary, adult remorse at the fulfillment of the nasty but necessary commitments of his job.

So, when Dylan Klebold’s distraught father (who had referred to his son as “pure normal”) says, “Our society feeds off our children,” who can argue?

In our clueless, blunted authority, we’re into panic mode. Shoe on the other foot, it’s Reefer Madness all over again. We rail at the Internet, as if it’s one giant Loompanics catalogue chocked with bomb recipes like Betty Crocker. We chastise Clinton, only one of us, after all, who sets such a slack example. There’s no respect in the nation, I tell you. A breakdown of religious discipline. Trouble right here in River City. What ever happened to good old repression, anyway? Is the “Just do it” ethic a tad out of control?

Rationalizations ‘R’ us. But what else is left? Rekindling the notion of the Bad Seed? The acceptance of palpable evil in our midst? More remakes of Village of the Damned? Then, of course, there is Hitler, ever the hardy perennial. It was almost astounding that in its earliest coverage, the New York Times was slow to mention that the shooting occurred on Hitler’s birthday. Seems as if the Hitler awareness, to tap into the DeLilloesque mystique that much of the Littleton incident recalls, was flagging at the newspaper of record. Despite 420’s recent codification as a street moniker for marijuana and the ominous specter of four and twenty blackbirds flocking from pies, April 20 had slipped as an infamous date in the public brainpan. If the killings had happened only a day earlier, on April 19, likely the Waco-Oklahoma City correlations would have made the opening graphs.

The mind of the parental unit reels. Just the other day, as my daughters were watching the Columbine coverage, my 9-year-old son sat at the dining-room table with four of his friends. Game Boys linked, they were electronically transferring Pokémons, the Japanese animation characters (a.k.a. Pocket Monsters) that are all the rage with their bunch. Indeed, in that day’s Times, with Columbine dominating above the fold, another story told of how Nintendo had made billions from Pokémon, the cartoon-show-and-action-figure complex recently held responsible for the alleged inducement of epileptic fits among youthful Japanese TV watchers. This said, compared with some of the other body-count extravaganzas my son has run up on the screen, Pokémon is pretty benign. The idea is to be an honorable, nurturing sensei for your menagerie of weird little creatures – not just to teach them to fight like cybercocks but also to help them evolve onward to a more ennobled state.

Yet who really knows about these things? As any old pinball wizard who could never beat a single level of Asteroids can tell you, if there’s a Time-mag-style generation gap fomenting, it is a disparity in hand-eye coordination as much anything of the mind or heart. Things are hooked up different these days. Needless to say, I have read over my son’s Pokémon manuals and still can’t grok the methodology by which Charmander, the baby “fire” Pokémon, mutates into Charizard, a 200-pound monster whose breath can melt boulders.

I watch my son and his e-coven of friends conduct their cyberséance and wonder: Who knows what malignancy lurks in the heart of the Poké-matrix? If, as it is fashionable to say now, memes (what used to be called ideas) travel like viruses, contagious and fast-acting like Melissa or Ebola, could not Pokémon, shiny, bright, and preternaturally popular, be the perfect surreptitious vector for such infection? Was this the transfer happening at my own kitchen table, a controlling Manchurian Candidate virus being downloaded into the wetwear of my own son and his buddies at this very moment? How long would it take for this murderous brainwashing to germinate? What kind of school-annihilating hardware might be available by the time this virus came full-blown?

Likely, by the time this next upgrade of teenage Frankensteins hatch out, their programming will be too well refined for them to exhibit such warning signs as watching Natural Born Killers twenty times in a row, or sharding up hundreds of Coke bottles for shrapnel like a personal Kristallnacht. Ever since teenagers were invented, back in the days of Elvis, they’ve been perceived as a kind of (self-propagating) Other. A separate adolescent species. Them of the dirty room, them of the smart mouth, them who cut classes. Them who once sat in your lap and now can’t stand the sight of you. Them.

Here in the city, we pride ourselves on at least partial immunity from these meme-loaded violence tropes. It might have been part of Eric Harris’s master plan to hijack a jet plane and crash it into midtown Manhattan, but here there is a sense that we New Yorkers are too practical, too hard-bitten, for Columbine-style psycho-killing. If someone stabs you for lunch money, shoots you because you’re black and they’re a cop, well, that’s earthly old New York. Saucer-freak suicides and role-playing pseudo-soldiers are not our style.

Yet the other day I found myself driving over to the William McKinley Intermediate School in Bay Ridge, where it was alleged that five Chinese eighth-graders, all of them in the top “E”-tracked classes, had plotted to blow up the building on graduation day. The five were also supposed to have compiled a “hit list” marking many of their classmates for death. The plans were overheard in the cafeteria, and police from the 68th Precinct arrested the kids, which led to much bewildered hand-wringing in the nearby Chinese community, known more for producing quiet, Stuyvesant-bound achievers (as these kids were – the band teacher, clearly distressed, bemoaned, “I’m out my best trumpet players!”) than mad bombers. In the wake of Columbine, the media descended on William McKinley, one of only two intermediate schools in Brooklyn named after an assassinated president. Before the 2:45 dismissal, as blue-haired ladies in large plastic glasses made their way along the sidewalk, the mid-spring Bay Ridge sky was cluttered with news-truck trees.

The students were equally poised. Well versed in the nuances of the Colorado coverage, they jostled for camera position and delivered their lines. The whole thing was “a big surprise,” said one 14-year-old, because even if the supposed bombers were “outsiders and unpopular,” they “weren’t that unpopular… . You know, they were hated, but they weren’t that hated.” No one “ever thought they’d do anything like this.” Later, it was said, the so-called bomb might have been little more than a Gilbert-chemistry-set-style assemblage of vinegar and baking soda. And despite several kids’ running around screaming “I’m on the hit list!,” that, too, might have been “a joke.” This isn’t to make light of the situation at McKinley – the threat, in context, was real, the reaction efficient and emotionally genuine. But there was a deadening lack of surprise in how absolutely, how instantaneously – faster than a speeding e-mail – the language and tenor of Columbine had transmuted to dese-and-dose Bay Ridge.

“No more pencils, no more books, no more teachers’ dirty looks” has gone ballistic. “Copycat” incidents multiply. The meme moves on. Standing on the steps of the William McKinley School as the media swarmed, Vincent Grippo, head of School District 20, said, “It’s not the system; it’s the society.” It’s comments like that that recall motorcyclist Marlon Brando’s being asked what he was rebelling against and answering, “What have you got?” Indeed, the horrific details of Harris and Klebold’s rampage aside, there’s been an undeniable current of sympathy for the murderers. As many times as the memorial crosses for Harris and Klebold in Jefferson County’s Clement Park were ripped down by the grieving and angry, someone put them back up again. The gnawing fact is, like the people they killed, Harris and Klebold were only kids. Somewhere, somehow, along the line they should have been protected, or slapped – anything.

In the end, that’s what it comes back to, kids and parents. Last week I was riding uptown on the No. 6 train and saw a woman reading a book called Get out of My Life, But First Could You Drive Me and Cheryl to the Mall, by Dr. Anthony Wolf, which, as many parents of teens know, is one of the better manuals on how to live with the teenage Frankenstein in your midst. The woman’s eyes and mine met; we acknowledged the presence of the book and sighed. Nothing needed to be said.

Still, I doubt Dr. Wolf’s book would have been much help to Mr. Thomas Klebold of Littleton, Colorado. In all this, I think of him most. Geophysicist; arguer for gun control; married to the former Susan Yassenoff, whose grandfather endowed the biggest Jewish community center in Columbus, Ohio, Klebold named one son for Lord Byron and the other after Dylan Thomas. Off the bare surface, he doesn’t sound so alien; the fellow father imagines himself having a pleasant, even far-ranging conversation with Mr. Klebold. Yet his son turned out to be a Jewish Nazi mass murderer. To think of Mr. Klebold’s grief is to swallow hard and walk shakily away.

The other night I told my daughter that since the Columbine massacre, the sale of columbine seeds has increased tenfold in some places around the country. Not that she cared, much. We were in a cab, going to a club called the Bank, a hangout for her goth crew, and I was far from an invited party. She was too busy arranging her black tights, black coat, black shirt, and black eye makeup to care much about the sales of pink and purple flowers. Despite reporting the mordant graffiti found on her high-school wall – 15 jocks got killed in colorado and all i got was this lousy trench coat – she was still mad that the media morons continued to associate Klebold and Harris with goths. “They said they got ideas from the lyrics of KMFDM,” my daughter railed. “That’s so stupid. Half the stuff the band says is in German and no one can understand it anyhow, so you know that’s not true.” Then she said it was time for me to split, because there was no way she was going into the Bank with her dad.

And let me say: I didn’t feel so good about it, watching my daughter standing there with her subculturist friends, all of whom seemed very nice even if made up like a brace of Morticias. No, it didn’t feel good at all seeing my daughter waiting on line to enter a club on Houston Street, past eleven o’clock, in her black velvet coat, those homie boys checking her out. But I’d already said okay, and there wasn’t any going back now, not without the most egregious of scenes. Then the bouncer, an obligatorily fearsome Mr. Five-by-Five, parted the rope and the line began to move. Industrial blare tumulted from the door. Already having waved good-bye, my daughter stood with her back to me, paused in the vestibule, awaiting entry. An orange light shone down from the ceiling upon her hair. From the day she was born, she has always had very beautiful hair. People remarked on it, always. Through all these years, her hair has never been cut. She just lets it grow, and it is beautiful still, long and shiny, hanging down. When we’re battling, as we are so often during these teenage times, I forget how beautiful her hair is, and how beautiful she is. But now, the orange light pouring down, the luminousness could not be missed. She just shone. And then the bouncer beckoned again, and my daughter entered the club, disappearing into darkness filled with noise. It was a moment to take a deep breath. Because you never know.