Look ahead: September | October | November | Memoirs

SEPTEMBER

Asia Majors

Jhumpa Lahiri and Monica Ali are redrawing the literary map of the Subcontinent and the West.

Jhumpa Lahiri shares a profound experience with fellow writer Monica Ali, but it isn’t what you’d expect. Yes, the two thirtysomething women of Bengali ancestry have both written dazzling first novels whose characters are startlingly specific and real yet stand in for essential cultural conflicts. But then, their situations—and their novels—are completely different. Lahiri, like her main character, Gogol, in The Namesake, was raised by Hindu parents in a New England university town. Her protagonist’s seemingly complete assimilation belies a deep identity crisis. Ali, on the other hand, is half-English and was raised in northern England; her novel, Brick Lane, follows a Bangladeshi woman in the London projects who chafes at Muslim tradition.

What these two writers genuinely share, though, is instant fame—hailstorms of acclaim and popularity that preceded even their first novels. “I was more perplexed than anything,” Lahiri says of learning that her story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, had won the Pulitzer Prize. “How could I possibly deserve this honor at this point in my life? I didn’t think they even considered debut works. I subsequently found out that they do.”

Lahiri had the half-finished Namesake to keep her grounded. Ali’s Brick Lane was still six months from publication when, based on a manuscript excerpt, Granta anointed her one of its “Best Young British Novelists”—one of only twenty per decade. It’s since become the only book the English are talking about this summer, and comes Stateside this fall with high expectations.

Despite the breathless Zadie Smith comparisons, there’s nothing arch or mock-epic about their novels. “It’s a fairly old-fashioned narrative,” says Ali. “It doesn’t have any particular gimmicks. There’s no dog learning to talk or anything like that.” Arranged marriages and naming customs notwithstanding, Ali and Lahiri are writing about typically fissile nuclear families. “I wanted to remain at the level of individuals and not so much cultural, ethnic divides,” says Lahiri.

Yet the rise of subcontinental writers and their diasporic compatriots is real. “I’ve seen the accusation that this is just a fashion, like Bridget Jones,” says Ali. “but I think there’s something else going on here, which is that we’ve got good stories to tell.” —Boris Kachka

• Details: Brick Lane, Monica Ali, September (Scribner), order on bn.com. Namesake, Jhumpa Hahiri, September (Houghton Mifflin Co), order on bn.com.

Inner Borough

With The Fortress of Solitude, Jonathan Lethem tunnels further into Brooklyn. Four years ago, Jonathan Lethem published Motherless Brooklyn, which made him a mainstream literary star and Brooklyn’s unofficial poet laureate. Now comes The Fortress of Solitude, a sprawling exploration of, among other things, an interracial friendship, the gentrification of Boerum Hill, the birth of hip-hop and punk, and the ineffable feeling of guilt that seems to burden those from the definitive outer borough. How autobiographical is The Fortress of Solitude?

There are lots of parallels. I grew up on Dean Street, and I went to public school. And my family arrived in 1968, so, yes, I was a witness to the very early, very homely gentrification of Boerum Hill, which prefigured the boom. In many cases, it was radical hippies and artists, these relative outcasts that broke the ground. It wasn’t as though some ghetto paradise was here and shattered by gentrification. Do you share the protagonist’s anxiety about gentrification?

It’s bittersweet for me. As fashionable as it’s become, Smith Street is very much still the street I walked along to junior high school. If I hadn’t grown up here, I’d be living in this neighborhood. I’d be drawn to it. It’s filled with people like me—I just happened to be from it. What are the similarities between Motherless Brooklyn and this book?

My books are all structured around some giant, gaping loss. That has to do with my mother dying when I was 14. But as a Brooklynite who grew up here in the seventies, living in a kind of collapsed universe founded on loss seemed pretty central to everyone’s experience. There’s the classic legacy of the Lost City, this sense of this disenfranchisement—Brooklyn was a great city of its own, and has this permanently injured sense that it was yanked away in a rigged election when it joined the greater city. —David Amsden • Details: The Fortress of Solitude, by Jonathan Lethem, September (Doubleday), order on bn.com.

Blue Book

TV legend Steven Bochco’s novel wouldn’t get past the censors. Steven Bochco isn’t exactly your typical debut novelist. As co-creator of Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law, and NYPD Blue, he’s spun many scandalous tales. Now he’s funneled his talents into Death by Hollywood, the story of a screenwriter (you guessed it) who witnesses a murder and decides to turn it into a movie.

What’s the biggest difference between writing TV scripts and writing a novel?

TV is such a collaborative adventure—you’re working in a chorus. Writing a novel is a completely singular effort. It’s just you, alone.

The book is bristling with the kind of language and sexual content that would cause the FCC to have a seizure. That must’ve been fun.

Absolutely. I think of it as my X-rated morality tale.

The book is peppered with cameos by real Hollywood players like Mike Ovitz, Tom Hanks, and Brian Grazer—not all of them flattering. Have any of them read the book?

Yeah, Brian’s a great friend. And he got a big kick out of it.

You sure he was being honest? After all, the book is filled with liars. Is there anyone in Hollywood who’s managed to be successful without lying through their teeth?

Sure. Me.

And why should I believe you?

Ha! I swear, personally I’ve never had to lie. And so, you know, there’s a big grin on my face right now. —David Amsden

• Details: Death by Hollywood, Steven Bocho, September (Random House), order on bn.com.

Best of the Rest of September

Train, Pete Dexter

A gritty L.A. noir novel from the former boxer, Philadelphia Daily News columnist, and National Book Award winner. (Doubleday.)

Where I Was From, Joan Didion

The owl-glassed author tackles her ancestors and the culture of California (note the past tense in the title). (Knopf.)

The Fifth Book Of Peace, Maxine Hong Kingston

A memoir of the acclaimed novelist’s efforts to re-create the book she lost in a devastating fire. (Knopf.)

Where’d You Get Those? New York City’s Sneaker Culture: 1960–1987, Bobbito Garcia

A glossy, gorgeous bible for sneakerphiles. (Powerhouse.)

Blood Canticle, Anne Rice

Red in tooth and claw, again. (Knopf.)

Taking On The Yankees: Winning And Losing In The Business Of Baseball, Henry D. Fetter

An economic history of New York’s winningest team and its biggest rivals. (Knopf.)

Mailman, J. Robert Lennon

A new novel takes readers inside the mind of a postal worker. It’s interesting, really. (Knopf.)

Look ahead: September | October | November | Memoirs

OCTOBER

YunquéAmericansWith a story that mixes Puerto Rican and Irish,jazz and the symphony, Edgardo VegaYunqué’s new novel is as American as thecity itself.I edit in themorning, and then at night I write hot,” saysEdgardo Vega Yunqué, who claims he works on sixor seven novels at once (“You don’t getyour relatives mixed up, do you?”) but until nowhas published only two, along with a story collection.For the 67-year-old Brooklynite (via East Harlem, theSouth Bronx, and Puerto Rico), the latest—whichFarrar, Straus & Giroux publishes this fall—isthe big one, both literally and figuratively. Rightdown to the title. No Matter How Much You Promiseto Cook or Pay the Rent You Blew It Cauze Bill BaileyAin’t Never Coming Home Again has akitchen-sink quality—which isn’t to itsdetriment—even after being edited down from1,200 pages to a meager 658.

“I didn’t want to feel restricted by astraight line of narrative,” says Vega. “Iwanted to go into the digressive mode ofnovel-writing. I used the idea of a symphony, but alsoof the mural. You see a lot of different faces; youjump around from one to the other and see therelationship between them.” The fleet-footedlooseness of jazz improv and Nuyorican slam poetrypervades Vega’s style. The plot, meanwhile, isboth simple (half-Irish, half–Puerto RicanVidamía Farrell finds her long-lost father) andsprawling (wars are fought, musical movements die,racial conflicts erupt). “My life hasn’tbeen all that exciting, and maybe that’s why Iwrite fiction,” says the writer, but he’sbeing a bit coy. “By the time I was 10 yearsold, before I left Puerto Rico, I had seen threepeople killed in front of me,” says Vega, whocaught another eyeful after coming to New York at age13 without a word of English. “Death has been abig part of my life.”

He found respite on the Upper West Side during thesixties and seventies, throwing parties, helping draftdodgers, and raising a family that includesstepdaughter Suzanne Vega. Perhaps there’s aparallel with Barry, Vidamía’s benevolentstepfather in his novel—though, says Vega,“Suzanne is a wonder child. Vidamía wasjust a bright kid.” In the nineties, he ran theClemente Soto Vélez Cultural and EducationalCenter, a vast Lower East Side visual- andperforming-arts space. All of which makes him one ofthe city’s great supporting characters. Is heready for more? “I don’t want much,”says Vega. “I live very frugally. I’mbasically a schmuck. I don’t want to be a star; I just want the book to do well.”—Boris Kachka• Details: No Matter How Much You Promise toCook or Pay the Rent You Blew It Cauze Bill BaileyAin’t Never Coming Home Again, by Edgardo VegaYunqué, October (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), order on bn.com.

Prisoners ofSex

In a new novel, Tama Janowitz hasn’t freedher slaves.Before Sex and theCity, there was Slaves of New York, TamaJanowitz’s breakthrough 1986 novel that skeweredthe trendy downtown art scene while simultaneouslyromanticizing it. And now she’s focusing herpenetrating eye on another New York denizen: theMarried Woman.Peyton Amberg is about a woman sodisillusioned with married life that she travelsaround the world having increasingly desperate affairsin an effort to fill the void. Where did the idea comefrom? Different things inspired me—MadameBovary, the concept of marriage as the solepursuit of so many women, the fairy tales, the“they lived happily ever after.” I wasexploring the notion of romantic love as a necessarypart of marriage—which in many cultures itisn’t. It seems like the emphasis today is onthe sadness of breaking up. We’ve lost the ideathat you were marrying because you were workingtogether as a team.In 1986, Slaves of New York made you ahousehold name. The women in this book are also slavesof the city. There’s so much emphasis on women beingbeautiful only if they’re 20 and the blondeideal. I feel privileged to live in Brooklyn, where Idon’t have to deal as much with the latestrestaurant, the latest raw diet, the latest designer.I think there’s a sense of desperation, a kindof doom here in New York. People come here andthey’re desperate to begin with, and thatdesperation is worked out in totally trivial ways.It sounds like you’re not a fan.I’m not negative about the city. For a writer,it’s divine! I just try to explore the worldaround me, and I can’t help but feel for thewomen I see.And what are you a slave of? I hate writing. But there are moments of supremetranscendence when I think, This is fantastic,because I’m not myself anymore.—Sara Cardace•Details: Peyton Amberg, by TamaJanowitz, October 22 (St. Martin’s Press), order on bn.com.

The Best of theRest of October

Colossus Of New York, Colson Whitehead

A love letter to the Big Apple, in thirteen parts.(Doubleday.)

The Night Country, Stewart O’nan

An intimate look at three souls revisiting their pastlives from the grave. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

Elizabeth Costello, J. M. Coetzee

One woman’s life, as told by a novelistwho’s won too many awards to count. (Viking.)The Funny Thing Is … , Ellen Degeneres

The lesbian icon tells all—jokes included. (Simon & Schuster.)

Love, Toni Morrison

The Nobel winner turns her pen on a wealthy hotelowner and the women who love him. (Knopf.)

Great Fortune: The Epic Of Rockefeller Center, DanOkrent

Love it or hate it, it’s the heart of (somepeople’s) New York. (Viking.)

Everything And More: Cantor & Zeno & Math & Abstraction, David Foster Wallace

A work on infinity that’s often as comic, ifthankfully less infinite, than Infinite Jest.(Norton.)

Smartest Guys In The Room: The Rise And Fall Of Enron, Bethany Mclean

Everything you ever wanted to know about the companythat became a catchphrase for corruption. (Viking.)

Look ahead: September | October | November | Memoirs

NOVEMBER

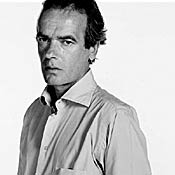

The Feud andProud

The nasty critical battle over Martin Amis’snew book seems like a part of its own plot.“The Booker Prizeis much fetishized, and I think too much attention ispaid to it,” declares Martin Amis, whoseupcoming novel, Yellow Dog, was justlong-listed for the award (only one other book of his,1991’s Time’s Arrow, has received anomination). “People like it because it reduceswriters to the same level as everyone else. Here theyare sweating in their dinner jackets and evening gownsjust like any other collection of suckers. It bringsthem into the swim of things.” Perhaps. But no writer ever turned downBritain’s most prestigious literary prize,either. So one suspects that Amis must secretly feelat least a little smug, especially in light of thecritical food-fight the novel has provoked. The book in question is a sprawling satire of Britishsociety that closely examines the dirty laundry ofeveryone from horny tabloid hacks to intellectualauthors to His Royal Majesty the King ofEngland—Amis even dedicates a significant bit ofattention to an uncooperative corpse. Anyone whocringes at impotence, constipation, and rambling,patchy narrative would do well to steer clear, butadmirers of Amis’s withering wit will findplenty to sink their teeth into. It’s aninvestigation into “the world ofappearances,” as he puts it, whether that be awanker boring holes into a centerfold or the kingrunning spin about a paparazzi shot of his bathingdaughter. “I’m also looking at thequestion of masculinity,” Amis goes on.“Male self-image, male desperation, maleweakness … and male strength.”It makes perfect sense, then, that Yellow Doghas inspired a clashing of mostly male egos both hereand abroad. Critics have alternately declared it awork of genius and reviled it as a total failure. Amisclaims not to have read the reviews but admits thatone critique, that of longtime admirer andTelegraph writer Tibor Fischer, who likenedreading Yellow Dog to seeing “yourfavorite uncle being caught in a school playground,masturbating,” did catch his eye. Amis’sresponse? “He was obviously high to write thatsort of piece. I think he’s even more of atalentless pipsqueak than I did before. ”—Sara Cardace• Details: Yellow Dog, by Martin Amis,November (Miramax Books).

Best of theRest of November

Genesis, Jim Crace

A hilarious yet revelatory tale of a man whosefertility gets the best of him. (Farrar, Straus &Giroux.)

Queer Street: The Rise And Fall Of An American Culture, 1947–1985, JamesMcCourt

A homosexual history, from Truman Capote to theChristian right. (Norton.)

Wolves Of The Calla, Stephen King

You know what you’re gonna get—but you want it anyway. (Scribner.)

By Sorrow’s River, Larry Mcmurtry

The final volume of McMurtry’s Bohemia-goes-Westtrilogy.(Simon & Schuster.)

Progress, Fran Lebowitz

More than twenty years after her last published book,here she is again. That’s progress? (Knopf.)

Old School, Tobias Wolff

The best-selling author of the memoir This Boy’sLife is trying fiction with this first novel. (Knopf.)

The Way To Paradise, Mario Vargas Llosa

A novelized double biography of Paul Gauguin and hishalf-Peruvian grandmother. Sound postmodern?It’s weirder. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

Still Holding, Bruce Wagner

The return of the novelist most often compared toNathaniel West. (But guess what: He’s better.)(Knopf.)

Hello Darkness, Sandra Brown

Texas, talk radio, and a titillating murder mystery.(Simon & Schuster.)

Serious Girls, Maxine Swann

A compelling Swann dive into the psyches ofboarding-school girls. (Picador.)

Look ahead: September | October | November | Memoirs

Have I Got A Story ToTell You

Memoir, memoir, in the fall, who’s thefairest of them all?

The Other First Lady

Reflections

By Barbara Bush

(Lisa Drew/Scribner; October)

Part two, after the matriarch’s 1994 book, opensat 43’s inauguration, then flashes back tosoft-focus stories about the Bushes’ eight coldyears under the reign of Clinton. Not so far off fromHillary’s thin tales of family andphilanthropy—but with more of the former andless of the latter, of course.

The Fighter

The Soul of a Butterfly

By Muhammad Ali, with Hana Ali

(Simon & Schuster; November)

Mostly in the realm of the “spiritualmemoir,” with a close account of thechampion’s long illness and religiousepiphanies. “It is after I retired from boxingthat my true passion began,” writes Ali.“I have embarked on a journey of peace andlove.” Not much fisticuffs, then—thoughit’s hard to write off a passionate defense ofIslam’s pacifism by someone Americans mightactually listen to.

The Storyteller

Living to Tell the Tale

By Gabriel García Márquez

(Alfred A. Knopf; November)

The first part of a planned trilogy, covering theColombian-born magical realist’s first 29 years,arrives in translation already a Spanish-languagebest-seller. Fans will find the seeds of many asetting and story, but the real fun might be inspotting Márquez’s acknowledgedembellishments.

The Euro

Autobiography

By Helmut Newton

(Nan A. Talese; September)

The photographer and self-styled transgressor recallshis birth into a prosperous Jewish Berlin family andhis narrow escape from the Nazis, after which hetraveled to Singapore and beyond, worked as a gigolo,and did time in an Australian prison. But it was afterhe moved to Paris that Newton’s sleek, naughtyphotographs made him famous. If the pretension andnarcissism rankle, skip to the dirty pictures.

The Thug

American Nightmare American Dream

By Suge Knight

(Riverhead, November)

The currently incarcerated Death Row Records mogulloved and feared for “bringing the ghetto intothe boardroom” tells a rags-to-riches-to-jailstory and sounds off on all those rappers—livingand dead—who’ve crossed his path, gettingthe last word as ever. Should be big in the suburbs.