Day One: Central Park

The grass pressing against the back of my neck is damp and scratchy, but I don’t care. How could I? It’s 2:48 in the morning, and here I am: lying down smack in the middle of Sheep Meadow, making snow angels in a snowless field, staring at a night sky that refuses to darken—it stops at gray-violet, some dim yellowy streaks that may be clouds, or maybe they’re pollution. Some version of nature losing the battle to a million lights and machines that are never turned off.

New Yorkers are prone to do ridiculous things, we all know this, and the other day I made a decision: to become an urban camper of sorts. I’d leave the cluttered, leaky, overpriced oasis of my apartment for … the wilds of the city. This is a town notorious for its ability to reinvent itself, constantly shaking off husks, and I was curious: How domesticated has New York City become in its cleaned-up, post-Giuliani incarnation?

The plan was simple: meander around, sleep in exotic places, see what hidden faces of the city revealed themselves. I fully realize there are people without homes for whom this kind of thing is not a mere adventure, and I wasn’t about to pretend that three days would give me a glimpse into their lives. Rather, I’d be like a cross between Marco Polo and that noble savage at NYU who spent a semester crashing in the school library. And what better place to begin this little sojourn than Central Park? So vast, so steeped in macabre, nocturnal lore. In 1999, the writer Bill Buford wandered in for the night, documenting the experience eloquently in The New Yorker. Buford, though, is of the generation schooled to equate “night in Central Park” with “certain death.” Me, I moved to New York seven years ago, and am, for better or worse, conditioned to think of it as a playland.

So here I am.

I entered at 9:45 p.m. by the Plaza entrance, the contents of my backpack as follows: a flannel sheet, two books (John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra and Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon, a thousand-page opus that I figure can double as a weapon), an inflatable Therm-a-Rest sleeping pad, a pen, a notepad, $100 (to appease potential muggers), three T-shirts, an unfortunate Paul Bunyan–ish hunter’s jacket, a flashlight, an umbrella and a half-eaten Kit Kat. I strolled around aimlessly, circumnavigating the lake, skirting the reservoir, the backside of the Met, past the Alice in Wonderland sculpture and that funny pond where people sail remote-controlled boats. By 1 a.m., the park had become markedly less crowded: There went those two chess players hanging out in that East Side gazebo; there went that crew of high-school kids who’d been smoking pot on a granite bluff. Even the lunatic man sitting by Shakespeare’s bust in the Literary Walk—who hooted at me like an owl—decided he had somewhere better to be at about 2 a.m. That’s when I made my way to Sheep Meadow.

Fifteen freshly mowed acres to myself. Is it frightening? No, not really. I am filled with something far more complicated than fear: mischievousness. In the Maryland suburbs where I grew up, this was an easy psychological state to come by. We’d do shots of Triple Sec thinking it was rum, sneak out of the house, walk around the block, throw rocks at some girl’s window, and feel like wily little menaces. In the city, I’ve raced people across rooftops, climbed water towers, and woken up in strange apartments without ever feeling mischievous in the least.

But wait a second—what’s that in the distance? A shape! Yes, a shape that appears to be … moving. A person! In my park? I frantically grab my backpack and run, fast, throat twitching, eyes burning, out of the field. I leap the fence like an Olympic hurdler who has to use his hands to get over the hurdle. I sprint down a pitch-black path, as if this is somehow a safer, saner place to be.

Wait a second— what’s that in the distance? A shape! Yes, a shape that’s moving. A person! In my park?

Soon enough I’m on a dirt path in a region of the park known as Mineral Springs. I can hear traffic again. That’s comforting. And what’s that I see up ahead? A woman who looks like somebody you’d never expect to see in the park at three in the morning: prim and put-together, wearing black leggings and a powder-blue tank top. She has two sleek golden retrievers in tow. How sweet. Or maybe not: As I get closer I see that she appears to be doing some sort of arrhythmic rain dance while watching her golden retrievers … in the act. This is for real. I duck behind a tree and stare. For five minutes. Ten. Twenty-five. I am mesmerized and, oddly, comforted: Here we are, two freaks in a city of freaks. I wonder about her life. Maybe she’s a lawyer who lives in the Dakota, or someone going through a divorce and acting peculiar in ways that have lately started to concern her friends. Who knows? By the time she rounds up her randy pups, 45 minutes later, I have trouble deciding who’s stranger: she for being a prim woman dancing as her dogs do the deed, or me for crouching behind a tree, and watching?

One thing is for certain: I’m exhausted, ready for bed. I notice that the tree I’ve been hiding behind is Y-shaped, a crook that I can sit in comfortably. I climb up and, using the rolled-up Therm-a-Rest as a pillow, manage to drift off for at least an hour, not aware that something about this position—legs astride, feet dangling—causes your entire body to fall asleep. Not just your toes, or fingertips, mind you: everything. When I wake up, I truly believe I am paralyzed.

Feeling swiftly returns, but it’s still dark out—4:30 a.m., I’d guess—and I need to find a new place to doze. I walk deeper into the park, toward Bethesda Fountain. It’s a bit more unnerving here, so quiet, so still, so un–New York. I find a welcomingly dense pine tree, and crawl inside to that spot by the trunk where it opens up like a hidden fortress. No one can see me here, this I’m sure of. I used to play hide-and-seek in these kinds of places when I was a kid. I inflate the Therm-a-Rest, prop my head up on the backpack, and drift off as comfortably as I do in my own home. That is, until the shouting starts.

“Bad boy! Bad boy!”

This is later, a few minutes, a few hours—it’s hard to tell. I have no idea what’s happening.

“Who’s a bad boy?”

I feel something thick and wet lashing against my face.

“Bad dog! Get over here right now!”

Oh. Not such a bad way to wake up, considering the alternatives. It’s a Saint Bernard, big, bushy, salivating intensely, licking my face with his mammoth tongue. Eventually, the beast gives in to his owner’s demands. It’s then that I notice the sun has risen, that I’d been sleeping for over two hours. Birds are chirping. Today is tomorrow. I am alive and well. I pack up my things and crawl out from under the tree to find the dog-walker right there, sitting on a rock. He is a dark-haired man, mid-thirties, with the serious, polished look of someone who works hard, goes to the gym too often, and, at present, doesn’t look pleased to see a stranger emerging from the brush.

“Good morning,” I say, smiling.

Day Two: The Bronx Zoo

Is there a more acutely narcissistic endeavor than breaking the law? The moment you hatch a devious plan in the private confines of your mind, something strange occurs: It’s as if the rest of the human population has receded into the background, and all eyes are on you. The sensation multiplies when the plan is enacted: You imagine helicopters circling overhead, code language whispered into walkie-talkies, men wearing infrared goggles using hand signals that resemble shadow puppets. Everyone is looking. Obsessing. Over you. I know you’re not supposed to say this, but breaking the law is awesome.

This is what I discover spending the night in the Bronx Zoo.

I arrive at 3 p.m., three hours before official closing time, out of the East Tremont Avenue subway station and into the zoo at the Asia Gate. I’ve never been here before and figure I’ll amble about, taking in the sights while covertly scoping out the grounds for the best possible place to hide for the night. Immediately, I discover some overgrown shrubbery twenty yards off the asphalt path running along the border with Bronx Park South, a bleak strip of cracked pavement, busted fire hydrants, project housing. No cameras, no lights: This is the place to crash. Just crouch down behind one of those trees and unroll the Therm-a-Rest. I file this information away. I’ve got hours to kill.

Zebras, ostriches, giraffes, wolf monkeys, bison, pythons, peacocks, polar bears lounging on scorching pavement, a horse-like creature called an okapi, a beetle the size of a softball, and a gigantic tour group of muttering, thick-calved Polish women who all look like my grandmother—these are some of the rare species I encounter. It doesn’t take me long to realize something about zoos: I hate them. They are places, it dawns on me, that mark three stages of your life. (1) Childhood: You see only the animals, the lions and tigers and bears, a thousand cartoons and coloring books come to life. (2) Adulthood: You see only the steel cages surrounding the heartbroken animals. (3) Parenthood: You see only the gleeful smile on your child’s face and laugh at your pseudo-serious, uptight, twentysomething self.

The zoo animals make strange gurgling noises that worry me less than the street sounds: sirens, car alarms, a few screams.

Or so I imagine. I’m firmly planted in phase two, a fact that becomes glaringly apparent as I enter the Congo Gorilla Forest, a place that, subway ads tell me, is incredible. I hike through the fake jungle. I study a fake snake as well as some fake monkey dung. Then, the grand finale: a dozen or so gorillas munching on leaves and scratching themselves in a glass cage that gives the impression that you’re right there with them. Hordes of people point and stare. Overwhelmed children weep. An ape that I imagine to be exactly my age in gorilla years approaches, pressing his hand against the glass and giving me a look that I interpret as follows: “I share 98 percent of your DNA, Mr. Homo sapiens, and, dammit, it’s that 2 percent that puts you on that side of the glass and me in here. My sister is getting on my nerves. My father is a silverback oaf who doesn’t get anything—just look at him. All he does is chew on that same stupid twig. Please help me … ”

Back outside, I notice a one-story bathroom complex low enough that I could climb onto its roof and spend the night there. This is better, right in the core of the zoo, not out on its periphery. Except for one slight problem: It’s nearing 6 p.m., and guards are starting to arrive, rent-a-cops sweating in pressed shirts and navy slacks, ushering stray wanderers like myself to the exits. One appears outside the bathroom complex. He is lean and muscular, sleeves rolled up to reveal a grim sea of shoddily executed tattoos, a man I imagine eats cinderblocks for lunch.

Five minutes later I’m back in the woods by the Asia Gate, leaning against a tree, wondering if that green stuff at my feet is poison ivy. Remember what I said about breaking the law being awesome? Well, it’s awesome for about an hour. I sit here, heart racing like a hamster’s, hearing guards roaming the paths, wondering if I’m going to get nabbed. A realization sinks in: No, I’m not, and this place doesn’t open back up for eighteen hours. Darkness falls. I close my eyes and attempt to meditate: gently crashing waves blend into a sunset, which transforms into my shower, my soap, a tray of bourbons on ice. Oh, never mind. I open my eyes.

In my imagination, I had the zoo to myself and the lions came out to play. I swung from vines with orangutans. I rode giraffes. Meanwhile, back in reality, a flash thunderstorm rolls in, leaving me drenched because I’m too nervous to open my umbrella. Every so often the animals make strange gurgling noises that worry me less than the sounds emanating from outside on the street: sirens competing with boom boxes, the occasional car alarm, a few screams … I doze off into a series of fitful naps. I begin to understand something else about breaking the law: Eventually, you want to get caught. Once you’re invisible, it’s not fun anymore. By the time the zoo reopens, and I’m long gone, I’m truly disappointed to know that none of the guards can see the stupid grin on my face.

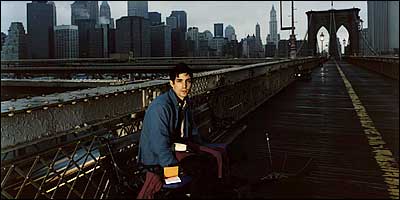

Day Three: The Brooklyn Bridge

I feel a raindrop on my cheek as I step onto the bridge’s walkway by City Hall. Not a great omen. Now comes an icy breeze, then more rain, coming down steady. This will pass. It will. It better: I’ve committed myself to spending the night out here, and according to the neon watchtower sign taunting me from across the East River, it’s only 10 p.m.

Seven minutes later, I’ve made it to the first of the iconic granite towers, where there is some semblance of shelter. I scrunch into a ball on the wooden walkway, wedge my $3 deli umbrella between my knees, forming the world’s most pathetic tent. I think of those annoying people with the gargantuan, domelike umbrellas, hogging the sidewalks during even the slightest drizzle. I envy them.

Below me, cars speed past, causing the bridge to vibrate. There is thunder, too, and more lightning, the sky flashing like a strobe every 94 seconds (I counted). For a while, this is scary—being drenched, over water, on a largely metallic structure—and therefore kind of fun, or at least time-consuming. Then the boredom sets in. A lone man strenuously avoids eye contact as he shoots by on a bike equipped with battery-powered reflectors.

I’ve gone mildly insane by the time I spot three bodies coming toward me from the Manhattan side of the bridge.

Hallucinations? No, these are real live young people—that’s all I can determine at first—which is enough to lift my spirits. They’re like me! Adventurers! Idiots! Who cares? They are here, approaching, tonight, now: a tall boy with a ponytail and two girls, one who looks very Banana Republic, the other very Comic Book Store. I try not to frighten them.

“Hey,” I say.

“Hello,” says Banana Republic.

“Just, uh, hanging out?” Comic Book Store asks.

I explain what I’m doing. I don’t hold back. I use the phrase “urban nomad” more than once, without irony. I don’t want them to leave. They seem nice, too polite to interrupt a jabbering wet man balled-up on the Brooklyn Bridge at 2:30 in the morning. When my soliloquy ends, I ask about them, what they’re doing, tonight, in life, whatever, and they tell me: students at Brooklyn College. Just saw Troy. Funniest movie ever. Decided to walk home, over the bridge, in the rain, because … because why not?

“And that’s that,” says Ponytail.

“Cool,” I reply, when what I’m really thinking is: Don’t leave …

“It’s raining pretty hard,” says Banana Republic. “We should, like, probably leave.”

“I’m going to stay a little while,” says Comic Book Store.

Is she serious? She is. As we watch her friends trot off, I invite her to sit down in my pseudo-tent. First thing I learn is that her name is not Comic Book Store, but Amye. Brooklyn-born and -bred, she’s 21 and writes an anti-fashion column for her school paper called “Sweatpants Fashionista.” We do that thing strangers in strange situations do: share secrets, about each other, about family members, about people we’ve dated, people we wished we’d dated. The rain starts to let up at around 4 a.m., and there are other signs of life. A mean-looking drifter guy who (thank God) just keeps on walking. A few dudes on bikes. At 4:30 a.m., a posse of women in black dresses staggers by, arguing.

“I’m a belly dancer,” Amye informs me as they disappear.

“Excuse me?” I say.

“I take lessons once a week. Wanna learn how to belly dance on the Brooklyn Bridge?”

We stand up, and she gives me a two-second tutorial: Keep legs shoulder-width apart, bend forward, then back—quickly—with just the tips of your shoulders, not your entire back. Her movements are fluid. She looks like a mermaid. It looks easy, but when I give it a go, I look the way I’d probably have looked if the lightning had got me: spastic, dangerous, tragic.

The sky lightens. Joggers appear, some ignoring us, others smiling. Amye tells me she has a Greek-mythology final in the morning, and needs to get going. I walk with her for a bit, thanking her for the company and finally saying good-bye. The rain has stopped. I see a bench. Looks like a fine place to lie down and close my eyes.