Willie Kathryn Suggs is walking me through a handsome four-story brownstone at 350 Convent Avenue in Harlem—or, as she puts it, “a house everybody goes gaga for.” The most successful and reviled real-estate broker in Harlem is small and intense, a prim, light-skinned black woman with wire-rimmed glasses, her hair pinned back in a clip. The house, a Suggs exclusive, is about to be listed at $3.875 million, up from the $380,000 it sold for just nine years ago. As she shows me the ornate parlor (“Four types of wood!”), Suggs mentions that she handled that sale, too, as well as one in between, in 2005, for $1.925 million. That’s two sales going on three, for a total of $6.2 million, and a tenfold run-up from the original price. From this place alone, Suggs stands to earn close to $400,000 in commissions.

Suggs has a habit—a compulsion, really—of talking nonstop and unself-consciously, changing subjects every few seconds, gesturing wildly and injecting cornball expressions that hint at the Wisconsin girl she once was, like “li’l ol’ me,” “works for me,” and “oh happy happy!” But a ripple of exasperation colors her voice as well, as though she’s convinced she’s the only sane person in an insane world. Out of nowhere, she’ll launch into derisive shrieks in odd cartoonish voices about how “stupid” people can be. “The biggest problem I have,” Suggs says, “is people think they know what Harlem is, and they haven’t a clue! First of all, they’re not brownstones. Brownstone is a building material, not an architectural style … ”

One of Suggs’s other favorite expressions is happy camper. This she reserves for the people who are sitting pretty in life, like the current owner of this house, a woman named Lovelynn Gwinn. Suggs had convinced Gwinn to buy another house in Harlem back in 1996. As the market exploded, that place soared in value, giving Gwinn the means and leverage to buy this one. Gwinn is now a close friend of Suggs’s, and runs Suggs’s firm’s Website. Gwinn also happens to be white. Their friendship, and the real-estate deals of which it was born, are Exhibit A among those who charge that Suggs is selling out Old Harlem. But to Suggs, Gwinn was just smart. She’s a happy camper. “People hate Lovelynn’s guts,” she says. “Now, did she do anything offensive? No. All she did was come to me to buy a house. I showed her how to buy a house.”

All you need to know about the current backlash against Harlem’s gentrification, Suggs says, comes down to the happy campers who bought at the right time and the stupid people who didn’t. Those who didn’t buy, she says, are just jealous, and Suggs never seems to miss a chance to rub it in—even if they’re black. “Black people can be racist,” she says, shooting me a coy look in the restored kitchen. “Hello? Reverend Wright? We’ve got our little racists running around. Some of them want Harlem to stay black. They actually think Harlem was built by and for black people. And we have to tell them all the time, ‘Excuse me, dear? We weren’t here. We didn’t even lay the bricks, right? Some of us worked on the subway tunnel, okay. But this was built by and for upper-middle-class white folks. We were the second and third owners. We were never—and I mean zero, nunca, never—the first owner of all these houses!”

But what about the people who would like Harlem to stay mainly black, I ask, even if it wasn’t always that way?

Suggs shuts her eyes and shakes her head. “You don’t have a God-given right to own your house till the end of time,” she says, “unless you actually own your house. We’re not talking about a country like Italy that’s for Italians. We’re talking about a neighborhood in the United States of America. There’s nothing that says Harlem has to be black!”

No part of New York has changed more dramatically during the recent historic real-estate boom than Harlem, and no broker has done more to drive that change than Willie Kathryn Suggs. In the past twenty years, Suggs, a former TV-news writer who hadn’t set foot north of 125th Street until 1984, has almost single-handedly pushed up sale prices on many Harlem homes to ten, twenty, even 40 times what they were previously worth. She was the first broker to break Harlem’s half-million-dollar barrier, in 1995, the first to reach $850,000, in 2000, and the first to surge past $2 million, in 2002.

But as Willie Suggs has changed the face of Harlem, much of Harlem has come to turn on Willie Suggs. Competing brokers and even some former sales agents now call her a predator, a bully, a thief—Willie Thuggs. Even by the aggressive standards of New York real estate, they say, she will boldly horn in on a listing, land a sale, or lay claim to a commission. “Everyone knows,” says one broker, “when you go to work with Willie Kathryn Suggs, you better watch your back.” Suggs has also become a lightning rod in Harlem’s larger gentrification debate. Critics say she has wantonly driven up real-estate prices until no one but the richest Harlemites could afford them and, worse, delivered much of the neighborhood into the hands of wealthy whites. Now every new sale she rings up seems to raise a pair of uncomfortable questions: Should Harlem be preserved forever as an affordable haven for blacks? Or should it be sold to the highest bidder?

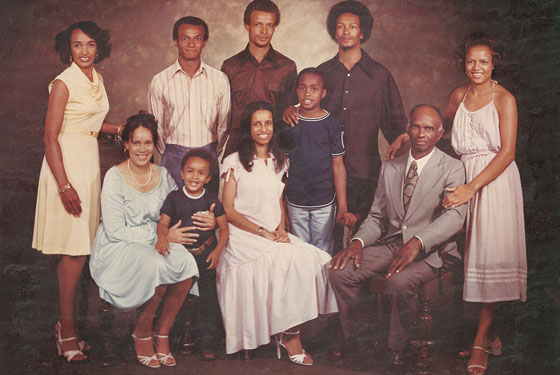

Suggs likes to cast herself as post-racial, or color-blind anyway, but race has defined her life from the start. Suggs’s parents moved her and her three brothers and two sisters north, from Mississippi to Milwaukee, in the early fifties, when Suggs was 3 years old. Willie only learned a few years ago from an uncle that they had left Mississippi because of a spate of lynchings. “I remember asking why we moved,” she says, “and my parents never gave us a straight answer.”

In Milwaukee, the Suggses were one of just a few black families on their street. Willie’s father, a college dropout who worked in an aircraft-components factory, had dark skin, but her mother was light enough to appear white. One white couple on their block moved shortly after their son fell in love with Suggs’s sister; Suggs says it was because her sister was black. A schoolmate once called her mother white, and Suggs was horrified. “I said, ‘My mother’s white?!’ And I ran home and said, ‘Mom! Mom!’ Somehow being white was this evil thing?” Suggs’s parents tended to discourage Willie and her siblings from seeing the world in racial terms, almost to the point of denial. She grew up determined to live as though race were irrelevant. “Racism is stupid,” she says. “The whole thing is stupid.”

When Suggs moved to New York, in 1972, her parents expressly discouraged her from moving to Harlem; they didn’t think the neighborhood was safe. Instead, she found an apartment on the East Side. In her building, white women would see her in the elevator and ask her if she had a free day to clean their apartments. “Oh, I was not a happy camper,” Suggs says. “They thought I was the maid.” A few years later, she moved to Hell’s Kitchen, where white guys would jingle the change in their pockets and ask her if she was working that night. “I’m thinking, I don’t need this in my life. From a maid to a hooker?” She laughs. “I was a lot smaller then, but I didn’t look like anybody’s hooker.”

In 1974, Suggs married a man named Victor Crichton, who was twenty years older than she. “He was very bright, but he had issues,” she says. “Everything came down to, ‘If I don’t get this job, it’s because I’m black.’ And I said, ‘I can’t take this. This is crazy. It’s not all about race.’ It’s all about race if you make it all about race.” After just a few years, the couple divorced. In court documents, which Suggs won’t comment on, she accused Crichton of attacking her at one point. Court documents also indicate that Suggs was briefly treated as an inpatient at Four Winds psychiatric hospital in Westchester at around that time. Suggs won’t comment on this, either.

Suggs attended a graduate program in history at Columbia and worked days at ABC, in a newswriting training program. At ABC, Suggs spent years working to be made a field producer, but no such job materialized. In 1984, she filed a federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint and later a lawsuit accusing the network of not promoting her because she was black. But ABC produced an internal memo suggesting that Suggs’s performance, not her skin color, was the reason she never moved up. In the memo, a producer named Howard Enders wrote that “deception, manipulation, half-truths, and an inordinate amount of second-guessing and backbiting are devices she uses quite liberally.” The case was eventually settled under sealed terms. But even today, Suggs maintains that her presence at the network had “pissed off some of the nonblack people.”

Suggs discovered Harlem, and the real-estate business, in 1984, the same year she filed her EEOC complaint. She’d always been interested in homes and home buying, she says. When she was a girl growing up in Milwaukee, her father used to take her and her brothers and sisters on long Sunday drives up Lakeshore Drive, stopping now and then to crash open houses. “We’re all a bunch of idiot house freaks.” When the rent went up on her one-bedroom apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, she decided to look for a place to buy. Priced out of much of Manhattan, she noticed an ad in the Amsterdam News (few Harlem properties were advertised in the Times then) for an entire townhouse, at 412 West 145th Street. The price was just $50,000; the monthly payment of mortgage, taxes, and insurance combined was lower than what she paid in rent—and the tenants brought in an extra $1,500 a month. “I said, ‘This is ridiculous!’ I said, ‘This house is too cheap! How can you buy a 3,800-square-foot functioning building for $50,000? That is stupid.’ ” (She still owns the building; today, it could easily sell for $2 million.)

After she closed, she realized that her broker hadn’t really helped at all. Just by walking the streets and making calls, Suggs felt she knew more about property values in Harlem than anyone else she’d talked to. She had an epiphany: “You know what? I could do a better job selling this.” Suggs got her real-estate sales license by the end of the year, turned part of the parlor floor of her new building into an office, and started selling houses on nights and weekends.

She took to her new work with an obsessive’s zeal, learning the streets of Harlem block by block, memorizing architectural styles. She remembers finding her first deal by answering a seller’s ad in the Amsterdam News for a house on 119th Street offered at $37,000. “I said, ‘Oh, that’s a ridiculous price! I can do better!’ And they said, ‘But you haven’t even seen it!’ and I said, ‘I already know the house. You’re the one that’s pink and has got a front that’s pushed out. Try $100,000.’ They said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘Duh!’ ” The owners agreed to give her the listing. She says she sold the place for $79,000.

That first year, Suggs had a closing every month, an impressive success rate for a beginner. What made her different was, in part, plain aggressiveness. Traditionally, Harlem homeowners kept their properties in the family; they didn’t buy and sell them for profit. “Harlem is an overwhelmingly African-American community,” Suggs says. “And they tend to buy the house, live in the house, die in the house, and the kids get the house. But as the prices started to move up, not all of the kids wanted to stay.” Unlike the old guard of Harlem brokers, Suggs was willing to sort through tangled title histories to find every owner of an old house, then try to convince them it was in their interest to sell. She had no problem helping the process along, spending her own money to fix up places to improve their sale prices if necessary, and even negotiating with rental tenants to relocate to clear the way for a sale. At the height of the crack era, she had what now seems like a prescient vision that property values in Harlem, depressed for decades, were poised to go higher. “The island of Manhattan is thirteen miles. What’s in the middle? Harlem. The only thing that was underpriced was the middle. It had to change, because there was no place else to develop.”

“Black people can be racist,” Suggs says. “we have to tell them, ‘We were never—never—the first owner of all these houses!’ ”

When the economy began booming and crime plummeted in the nineties, white buyers became interested in Harlem for the first time in decades. Some began migrating north, Sunday Times real-estate section in hand. Suggs remembers the first “If You’re Thinking of Living In … ” piece about Hamilton Heights. “Everything changed. We’d scheduled an open house on Hamilton Terrace. And this couple showed up. And you know, rich people look rich. I mean, they just look rich. They pull up in their chauffeur-driven car. The husband gets out, opens the door for the wife, they walk up the steps. ‘Oh dear, we hope we’re not too late. We just read about Haaarlem and thought we’d take a driiiive.’ ” Where the old Harlem brokers might have paused before showing white buyers around the neighborhood, Suggs had no such reservations. To illustrate her point, she shows me a place on 120th Street that just sold for $1.65 million to a white empty-nester from Central Park West. “Do you know how many black people looked at the house and didn’t make offers anywhere near what this guy made?”

By the mid-nineties, there was a gold-rush feeling in the neighborhood. Suggs, who had quit her job at ABC in 1993 to sell homes full-time, began racking up sales records—$500,000 for 60 Hamilton Terrace in 1995, $650,000 for the same place in 1999. In 2000, she sold 416 Convent Avenue for $660,000, 420 West 144th Street for $750,000, and 54 Hamilton Terrace for $850,000. In August 2002 she broke the $2 million barrier, selling a house for $2,050,000. She won’t reveal the location, she says, because the price was so high at the time that the buyer didn’t want to go public. “Nobody believed I could sell it for that much,” Suggs says. “I said, ‘Watch me.’ ”

Suggs still operated out of her house with just one phone line; she stored many of her files in garbage bags. But now she had a staff of young sales agents. Together, they were handling some 60 closings a year. To hear at least one former colleague tell it, Suggs became obsessed with her own success. At one point near the peak of the boom, says Laura DeJesus, a former sales agent, Suggs interrupted a staff meeting to say, “I’m the greediest person you will ever meet in your life. And I just want you to know that.” “We all started laughing,” DeJesus says. “She leaned forward again. She said, ‘I am not kidding. This is not a joke.’ ”

In 2005, Suggs bought a pretty four-story limestone townhouse on a prized block of historic Hamilton Terrace, her second property in Harlem. She paid $895,000; once it’s renovated, she says, she believes it could sell for $4 million. What makes the purchase notable, her critics say, is that Suggs had originally been hired to sell the place. The owner, a woman named Henrietta Rouse, had lived there since 1976. Some suspect that Suggs deliberately never found a buyer until she could snap it up for a below-market price. Suggs paints herself less as an owner than a steward of the property. “Oh, I love Mrs. Rouse,” she says with a giggle, showing me around the house one sunny afternoon. “She’s like my older sister. This is really her house. I’m just taking care of it.” But others see it differently. “I remember the conversations,” says Bianca Ferraioli, a retired broker who once worked for Suggs. “Willie wanted to put it in her nephew’s name, because she thought it would look suspicious if she put it in hers.”

Suggs has frequently been accused of dubious, and even illegal business practices. More than a half-dozen of her former sales agents have reported her for various offenses. Some say they saw Suggs misrepresent homes to potential buyers, and even to her own sales agents. One trademark Suggs move is to hold up closings with last-minute demands for money. Having voluntarily spent her own money on improvements to boost a property’s sale price (and her commission), Suggs would then file liens against the property to force the seller to reimburse her. In 2004, she was sued for a lien she presented for just $8,995. In 1999, six former sales agents filed a joint complaint with the state office that grants brokers licenses, accusing Suggs of not paying the portion of commissions she’d verbally promised them. The complaint went nowhere (a common outcome for that office, some brokers say), but two sales agents remember Suggs responding to objections by saying, “This is Harlem. We make up the rules as we go along.” “Every commission check she’s given me has bounced,” says Micki Garcia, who worked for Suggs a few years ago as a sales agent. “Three times I had to take her across the street to the bank to make sure there were funds.”

Suggs has also been accused of being vindictive. “When she fired someone, she’d create a conspiracy against the person after the person was gone,” says Garcia. “She’d talk about that person with new people, so they’d all have the same impression. She just got threatened whenever she saw anyone start to grow.” And Suggs had a strange tendency to call the police whenever she decided to fire someone. She did it to Marilyn Henderson in 1998, and Aaron Willoughby in 2000, and Lisa Downing in 2004. These people, Suggs tells me, were disturbing the peace—some were pressing her for money, others were confronting her in different ways. “You cannot make a scene. I don’t care who it is. In my family, if people misbehave, you call the police. That’s what they’re there for.”

No one had much success pushing back against Suggs until 2000, when she accused a sales agent named Raquel Brown of stealing files from the office in the middle of the night. Young and ambitious in her own right, Brown had just handled a record-breaking $660,000 sale at 416 Convent Avenue. Shortly after, Suggs filed theft charges against Brown at the 30th Precinct, and later sued her. Brown countersued, denying any theft and accusing Suggs of “abuse of process,” or using the legal system for personal ends. The lawsuits wound through the courts for seven years. A judge determined in 2003 that there had been no theft of files—that Raquel Brown was just working from home like many sales agents do. The abuse-of-process case made it to trial last November. After a short deliberation, the jury ruled against Suggs, awarding Brown $2.6 million, one of the highest judgments ever in an abuse-of-process case in New York.

The judge later reduced the award, and the parties reached a settlement. Neither side will discuss the terms, but Brown says she feels vindicated; some close to her have suggested that Suggs ought to lose her real-estate license over the matter. “Will the public place its trust in a broker found guilty of abuse of process?” Brown asks. “How her story is going to end will be very interesting.”

It’s a sunny Thursday afternoon, and Suggs is showing me a tidy one-bedroom co-op she is selling on a high floor of a doorman building on 145th Street. There’s a brilliant south-facing view of Harlem, and Suggs is pointing out the major landmarks—City College, Columbia University, the tall but dingy Adam Clayton Powell building. She takes special note of the larger condo and co-op developments, particularly those that are friendly to new people from outside the neighborhood. Then I ask Suggs what the word gentrification means to her.

It’s not about identity politics or cultural preservation, she tells me. It’s about math. “You ask the average African-American resident of Harlem,” she says, “they’ll say it means ‘nonblack people are moving in and we’re being forced out.’ And that’s not gentrification. Gentrification means a change in the social, economic makeup of a neighborhood. Not necessarily racial. What is going to change, is anybody with money who can afford the house is gonna buy the house. And if the house is very expensive, because the black middle class is smaller than the white middle class, there will be more nonblacks buying the houses.”

Of course, the issue is more complicated than that. No one wants to go back to the bad old days of sky-high murder rates and bombed-out tenements. But that doesn’t mean everyone is in favor of unchecked gentrification, either. In one of the most expensive cities in the world, Harlem has long been one of the few reliably affordable neighborhoods, and neighborhood advocates say that’s invaluable. “It’s immoral to me for people to come and say, ‘I deserve to live here more than you do because I have more money,’ ” says the architectural historian Michael Henry Adams, author of Harlem Lost and Found. At the very least, the opponents of gentrification say, the pace of change is excessive. The Bloomberg administration is rezoning all of 125th Street for more than 2,000 new market-rate condos, as well as office towers; along the East River, $1 million condos are coming next to the site of a future shopping mall; and to the west, Columbia is threatening to swallow a whole swath of the neighborhood. That’s all on top of Suggs and other brokers’ driving up home prices. “This is beyond gentrification as we commonly know it,” says Craig Schley, who heads a community advocacy group called VOTE People. “Gentrification typically refers to stronger or more viable people taking advantage of weaker people. Here, everybody’s getting eaten up. The haves are getting eaten up by the have-mores.”

Then there’s the even trickier question of race. Suggs and others insist that trying to preserve Harlem as a mainly black neighborhood is just reverse discrimination. But others say Suggs and others like her are hiding behind principle for their own selfish ends. “This woman,” says Nellie Hester Bailey, who heads an activist group called the Harlem Tenants Council, “has reaped a bounty off the backs of poor and working-class people.” Philosophically, there are those who say Harlem should be to blacks, to use Suggs’s analogy, as Italy is to Italians. Or maybe the better comparison is to Israel—a haven for the historically oppressed. Still others simply sense something important disappearing in Harlem, and want to stop it. “I feel about Harlem the same way I feel about Chinatown or Florence or Venice, or even New Orleans,” says Michael Henry Adams. “A place like this without natives living there becomes pointless.”

Suggs doesn’t have time or patience for any of this thinking. Harlem has too many rich people now? “I want the new people who come in to be doing well,” she says. Other people can live elsewhere, she adds. “Not in Harlem, but in the Bronx. Maybe Cambria Heights in Queens. Eh, Brooklyn’s kind of dicey. People want what they can’t have, and they can’t have it because of choices that they make.”

Should Harlem stay mainly black? Racism is racism, she reiterates. Besides, “you need this mix,” she says. “I don’t want my neighborhood to be all black or all white. That’s not how I grew up.”

The practical reality, Suggs maintains, is that Harlem will remain black no matter what. “Look out the window,” she says. “What are we seeing? What are those big buildings? That’s public housing. Who lives in public housing? Black folks. Public housing, you’re rent-stabilized or rent-controlled. You’re not leaving unless you go feet-first. The majority of people who live in Harlem are renters. The majority of those are rent-stabilized or rent-controlled. We’re not going anywhere.” Yes, Suggs says, there are more rich white people than rich black people, and so more whites will buy expensive properties than blacks. “That doesn’t mean that every black person who owns a house in Harlem is going to sell our house to a white person. Some of us are never going to sell our houses. We’re trying to buy more if we can.”

For Suggs, nothing’s stopping anyone, black or white, from gaining a stake in the new Harlem. To her, freedom from the shackles of race and poverty, and entry into the landed class, is just a real-estate course away. She says as much when I ask her about the argument that blacks as a class have been economically discriminated against—and are therefore being disproportionately pushed out. The question makes her face tighten; finally, she snaps.

“Bull crap! That’s bull crap. Nobody stops you from paying 50 cents for the Post, 50 cents for the Daily News, $1.25 for the New York Times. Guess what they have? They have articles on real estate! They have a real-estate pullout section! If you simply read it, you say, ‘Oh, there’s a program. If I take four classes, a total of eight hours in this class, sponsored by Harlem congregational churches, right? I can get up to $70,000 free.’ It’s called a grant. Now, if you had $70,000, do you know what Willie could sell you? We sold a five-and-a-half-room co-op for $90,000. All he needed was $20,000. I’ve been privileged to speak to those classes in the last year, and there are black folks in there, there’s white folks in there, there’s foreign-born people in there. And I’m thinking, Well, why isn’t the class all black? Because a whole bunch of black folks, for whatever reason, just don’t bother to go. So what’s your excuse now? I just told you where you can get $70,000. You don’t need any money!”

The last time I meet with Suggs, she’s showing me another place in Hamilton Heights that she’s getting ready to sell. I ask her if the guilty verdict in the abuse-of-process matter might endanger her broker’s license. “No,” she says. “No, no, no.” She says no twenty times in all, shaking her head sharply, as if each no will make the verdict go away. “I’m abusing process by telling the authorities that you removed things without my permission? Anybody who knows what happened knows that’s illogical!”

Still, she can’t get the idea out of her head. She picks up her cell phone and calls her lawyer. “Mortykins! Is there any way the Department of State can say, ‘Oh, you aren’t worthy of being a broker, because you were found guilty of abuse of process,’ which is bullshit? … So abuse of process has nothing to do with it? Okay … No, no, no. He’s asking, like, if you’re a sex fiend and you’re convicted, you shouldn’t be working at a—a—a day-care center, so if you’re a real-estate broker and you’ve abused process—Grrr!—how can you be a broker? … Thank you!”

She hangs up, smiling again. “That’s what I thought.”

Even if Suggs doesn’t lose her license, she’s working in a different Harlem now, with new challenges. The boom is waning in Harlem, as it is everywhere. Competition from real-estate giants like the Corcoran Group and Douglas Elliman is getting more intense. And the Harlem customer base is changing. When the only people who can afford to buy in the neighborhood are wealthy, a homegrown broker who works without a real office may not be exactly what clients are looking for.

For a woman of her wealth, Suggs leads an oddly spartan existence. She’s only now getting around to renovating her two buildings, and she hasn’t had a working kitchen since 1991. (She loves takeout, she says.) She says she gives much of what she earns to her fourteen nieces and nephews. Her work is her life, she says, and she has no plans on giving up anything.

“Look,” she says, “anybody who doesn’t like me is not gonna like me no matter what I say, no matter what the court says. I spend my time working and selling the houses and doing what I’m supposed to be doing, which is all that I’ve ever done. Honey, I’m not going anywhere. I’m not about to start a new career, okay? I’ve invested too much time. I also like what I do, you know? I don’t worry about anything. I tell my agents if you’re going to be a Realtor, don’t expect to be liked.”

She laughs. “People like lawyers more than real-estate brokers. I mean, we might as well be Reverend Wright.”