When the Eliot Spitzer scandal broke in March, I had only sympathy for him: another middle-aged married guy tormented by his sexual needs. I’m 52 and have always struggled with the desire for sexual variety. Everyone gets an issue, and that’s mine; it’s given me pleasure and pain, and jolted my marriage. I’d only talked about my issue with any honesty over the years with about six or seven people, and when you leave out my wife and a therapist, they are all men.

So the conversation had a conspiratorial male character. When people at dinner parties cried out, “What was Spitzer thinking?” I whispered to a friend that I knew damn well what he was thinking: He wanted some “strange,” to quote the old Kris Kristofferson line. Or we passed around JPEGS of Spitzer’s date, Ashley Dupre, and commented on her luscious body. The governor’s plight had the effect of outing me. When I told one married friend about my torment, he cut me off. “Everyone in our situation has had one or two episodes. Straying, wandering eye, a blowup. If you have a pulse.”

When I decided to write about it, the novelist Frederic Tuten offered a warning about the sanctity in which Americans hold monogamy in marriage. “You can go against it in life, but don’t speak against it. It makes you a monster. Who speaks against it? And this creates a dichotomy, between what we live and what we profess.”

The challenge for me was to explore the dichotomy, of which Spitzer, with his hot wife and public moralizing and complicated secret life as Client 9, was the most flagrant recent example. Then there was his successor, David Paterson, and his affair, or two affairs, or—we lost count. And then Congressman Vito Fossella and his two families. What did it mean about men—and marriage—that this kind of duality was possible?

Even sexologists aren’t clear about issues of sex in a long-term relationship. “There is all this political and social commitment to marriage, yet this is what our news is made up of, these infidelities,” said the first person I called, Jennifer Bass, communications director for the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University. “This is something we don’t understand. There’s research on relationships and research on sex, but putting them together is not so easy.” The result is that our understanding of married sexuality tends to be a rich mix of gossip, statistics, and cliché. “One week it’s ‘everyone’s having sex,’ and the next week it’s ‘the sexless marriage,’ ” Bass said. Having visited many of those clichés myself, I could look back and say that baby-boomers had changed a great number of sexual mores and traditions, from premarital sex to naming the G-spot. In his book on the history of sodomy laws, Dishonorable Passions, the law professor William Eskridge Jr. has shown how non-procreative sex had slowly but surely gained a place in American life, a cultural tide pushed by nonconformists and artists—not to mention enlightened affluent boomers. But monogamy has so far withstood the revolutionary impulse. Consider that Fossella is being pilloried for having an affair, while his sister Victoria Fossella, according to published reports, is openly gay, lives with a partner, and has adopted children that her partner has borne. No, these are not the same thing, and Victoria’s choice doesn’t yet have a place of honor—but it’s taken for granted, as it wouldn’t have been 50 years ago.

An article of faith among the men with whom I discussed these issues (and an idea ignored, if not contested, by most of the women I know) was that the hunger for sexual variety was a basic and natural and more or less irresistible impulse. “I haven’t ever seen anyone who doesn’t deliver on every single demand their sexuality makes on them. We make the mistake of thinking some people have a stronger will, they don’t,” says a forward-thinking friend. “There is no more unnatural principle of social organization than sexual exclusivity.” But like other of my male sources, he didn’t want me to use his name. “Don’t get me divorced!” was the refrain. All of these guys nursed a fantasy, as quaintly surreal as an old tinted postcard, of a perfectible world in which we might have sex outside our primary relationships and say that it doesn’t mean anything.

Housed in a handsome townhouse on the Upper East Side that might contain a huge and happy Tolstoyan family, the Ackerman Institute for the Family is a leading center for couples therapy, and when I met its president, Lois Braverman, I brought up the point that Alan Dershowitz and many others have made re Spitzer: Aren’t Europeans more evolved about marriage?

Braverman pointed out that American habits, even on the Upper East Side, have a moralistic component. That affects men too. “I’m not a sociologist,” she cautioned. “But we have a history of puritanism as a very dominant sensibility in the United States. That’s not the dominant sensibility in France or Italy. My observation is that often when people are having an affair, they get very involved and they start questioning their attachment to the marriage, which becomes very threatening to the marriage’s survival. The husbands here don’t treat the affairs in the way we imagine Europeans treat their affairs.”

I told Braverman that I’d sent an e-mail to 50 married guys and put an ad on Craigslist; one of my respondents was a guy in his sixties who said that his wife was no longer interested in sex, so he just went and had lap dances and maybe a little more, and no one was hurt. “I don’t find it’s morally wrong. What’s morality—the sex taboo. This is totally private,” he’d told me. “I can’t change my wife’s point of view.” I’d asked him if he felt shame. “I do, but a need is a need. For a woman too. A woman has needs. Women are much more mysterious than men.”

Braverman was impatient with the idea that the marriage couldn’t fulfill this man’s needs. “What does it mean that she’s not interested? How long has she not been interested? We know that age does not end sexual arousal or interest, we know that’s a myth. Was there some argument about something else, feelings hurt? What happened? Did one person feel abandoned?”

I felt that Braverman was missing the point, and making me feel guilty to boot. It was the old male-female morality play. I would insist that the man’s behavior didn’t mean anything to the relationship, but she saw it as a betrayal of trust. She also said that some people have strong relationships without “physical intimacy.”

Recent science has tended to support my side of the argument. In the last fifteen years, the evidence has grown that our sexuality is hardwired, and the science is changing the culture. My sister Alice, a respectable suburban woman happily married for eons, says that she’s come to respect the fact that sexuality runs the gamut: Some people seem happy with a sexless marriage, while others aren’t built for monogamy. The only morality she hangs on to is how honest one person is with the other about their stuff going into a marriage.

My sister has been influenced by evolutionary psychology, the widely publicized theory that the sex drive is genetically programmed. One of the leaders in the field, David Buss, author of The Evolution of Desire and a professor at the University of Texas, says that men’s genes program them to seek many mates and try to monopolize the reproductive lives of those mates; think of the manners of the Fundamentalist Latter-Day Saints sect’s sprawling compound in Texas, in which the older men ran the younger men off and had as many of the girls—as young as 14—as they wanted. But women are also programmed for infidelity, Buss says. They have a drive to monopolize the economic resources of their mate, according to the theory, but also to keep a man or two in reserve, because men die earlier than women, or men go off, and women need protection. Recent analyses of genetic databases reveal that fully 10 percent of people have different biological fathers from the men they name as their fathers, Buss notes; that’s evidence of women cheating. But Buss says the difference between the genders in the desire for variety is not minor (as, say, the gender difference in height is, about 10 percent on average); it is staggering, “like the difference between how far the average man and woman can throw a rock.” Consider the Website meet2cheat, in which married people find one another for recreational sex; it charges $59 for a man’s three-month entry fee, $9 for a woman. Cheating wives are harder to come by. “Women are going to get bored, just like men, but I don’t think they have this driving constant need,” says Nancy Heneson, a science writer who’s covered evolutionary psychology since its early days.

The point was driven home to me by a transgender man who responded to my ad. Jay was a woman for nearly 50 years till he made the transformation a couple years ago. The testosterone regime he underwent produced great changes in behavior—as well as tolerance of infidelity. “There is a significant uptick in casual sex, a lowering of inhibitions, and far more interest in sexual variety, including bisexuality and fetishes, BDSM, etc.,” Jay said. “Personally, I have noticed I have a newfound ability to completely divorce sexuality from emotional commitments.”

As even the evolutionary psychologists will tell you, though, life isn’t just chemicals. “Cultural and social attitudes come in and sweep everything off the table,” Heneson says. Society is far more judgmental about women who cheat than men; just read Anna Karenina. Anna Hammond, an arts executive who has written on feminist subjects, points out that infidelity is more costly to a woman than a man: It tends to end a marriage when a woman is discovered, while a marriage “absorbs” it in the man’s case.

“Men have more freedom to act. It’s not because men have more desire or are genetically programmed. It’s because the social and economic ramifications of it are so much more severe for women.” Hammond told me of women friends who have had long affairs and only told one or two close women friends about them lest word get out. The women got a lot from the affairs, she said, passion and a sense of themselves as sexual. “Women do these things, too, but they do them completely in secret.”

Marital passion—and its absence—was a major theme in the responses to my e-mail. “I think that marriages in which both parties are members of the meritocracy seem to be especially vulnerable,” said one friend in Los Angeles. “I see in the [Spitzers] something of what I see in other well-educated power couples—a career trajectory that excludes passion and lust. I know a lot of guys who seem trapped in sexless marriages.”

A New York friend expanded the point. “My wife tells me that none of her friends are interested in sex … Do middle-aged, married women who are no longer interested in having sex with their husbands expect them to remain faithful? They don’t want it thrown in their faces, but if they think about it for a bit, they have to realize that that intense need is being met somehow.”

There is today an extensive literature on revitalizing sexuality in marriage. Lois Braverman at Ackerman had recommended Passionate Marriage, by David Schnarch, which counsels couples to try to have orgasms with their eyes open, along with techniques of “differentiation” to cut boredom. My wife has a copy of the book, but when she saw me on the couch reading it, she mocked me. “That’s chick lit,” she said. “How much of it really works?”

Certainly, I recognize in Schnarch’s work and another Braverman suggestion, Mating in Captivity, by therapist Esther Perel, some of my own techniques to keep my marriage sexual—an important aim, even if I fall a little short of the national average for frequency of intercourse in marriage (about 66 times a year). Sexlessness in a marriage is defined as intercourse fewer than ten times a year.

The common answer married men come up with for the deficit seems to be something everyone’s now wired for. “[P]orn is the norm,” Mark Penn, CEO of Burson-Marsteller—and Hillary Clinton’s former chief strategist—said in his book Microtrends. Penn reported that the marketplace for porn is gigantic, dwarfing the national pastime of baseball. “And when women realize it, will it change the way they view their colleagues, bosses, husbands, and boyfriends?” It’s not just men. Erick Janssen of the Kinsey Institute has written, “Relatively large numbers of married men and women indicate using the Internet for sexual purposes … but the impact of this on marriages has, as yet, not received much research attention.”

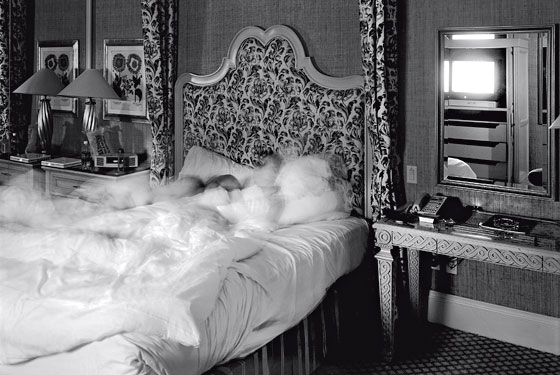

One friend had lamented the Internet’s effect on his life. “There has got to be an outlet outside of marriage. I think that’s pathetic what I do, a healthy, successful, upbeat kind of guy. Am I consigned to that lonely pleasure?”

His wife has some idea of his sexual needs, and doesn’t really want to know more. One man told me that when his wife wasn’t available, he snuck out to massage parlors in a “primal state” or watched porn. He felt no compunction about this; it was part of the never-ending battle of the sexes.

“Porn captures these women [its performers] before they get smart,” he said in a hot whisper as we sat in Schiller’s Liquor Bar on the Lower East Side. Porn exploited the sexual desires, and naïveté, of women in their early twenties, he went on, but older women had come to terms with that. “The most one can expect is that women will cede that area, in porn, a period when you can observe us before we have power, because it ain’t going to happen again.” He spoke of acts he observed online that his wife wouldn’t do. “It’s painful to say, but that’s your boys’ night out, and it takes an enlightened woman to say that.”

Our conversation had a male-conspiratorial tone that was faintly ridiculous—we were like the two straight guys in a French farce. I wondered what the tattooed waitress heard—she was probably having more sex than either of us. Studies provided to me by Kinsey researchers suggest that over the last 50 years, sex and marriage have become increasingly, well, decoupled. One factor is that young people are putting off marriage longer and longer, causing women to have 8.2 years of premarital sex on average, 10.7 for men. “The link between sexual activity and marriage is breaking down,” the researchers wrote.

Susan Squire, the author of a forthcoming history of marriage called I Don’t, told me that marriage wasn’t made to handle all the sexual pressure we’re putting on it. For one thing, the average life span is far greater than it was 100 years ago; what is marriage to do with all that time? And in days gone by, marriage was a more formal institution whose purposes were breeding and family. Squire says that cultural standards of morality have changed dramatically. In ancient aristocracies, rich men had courtesans for pleasure and concubines for quick sex. In the Victorian age, prostitution was far more open than it is today. America is a special case. By the early-twentieth century, she says, the combined impact of egalitarian ideals and the movies had burdened American marriage with a new responsibility: providing romantic love forever. Squire says that the first couples therapy began cropping up in the thirties, when people found their marriages weren’t measuring up to cultural expectations.

One man I spoke to said his wife was no longer interested in sex, so he went and had lap dances and maybe a little more. “I can’t change my wife’s point of view.” I asked him if he felt shame. “I do, but a need is a need.”

“Marriage isn’t the problem; it’s the best answer anyone’s come up with,” Squire says. “Men and women are equally oppressed by expectations. Expectations are ridiculously high now. Nobody expected you to find personal fulfillment and happiness in marriage. Marriage can be very satisfying, but it’s not going to be this heady romance for 40 years.” Marriage involves routine, and routine kills passion. “What does Bataille say?” Squire continues. “There is nothing erotic that is not transgressive. Marriage has many benefits and values, but eroticism is not one of them.”

A long and supportive marriage may be more valuable than a sexually faithful one, Squire says. “Why does society consider it more moral for you to break up a marriage, go through a divorce, disrupt your children’s lives maybe forever, just to be able to fuck someone with whom the fucking is going to get just as boring as it was with the first person before long?”

Sitting in Schiller’s, I explained Squire’s history to my friend and suggested that we could change sexual norms to, say, encourage New York waitresses to look on being mistresses as a cool option. “That’s fringe,” my friend said dismissively. Wives weren’t going to allow it, and we men grant them a lot of power; they’re all as dominant as Yoko Ono. “Look, we’re the weaker animal,” he said. “They commandeer the situation.” He and I love our wives and depend on them. In each of our cases, they make our homes, manage our social calendar, bind up our wounds and finish our thoughts, and are stitched into our extended families more intimately than we are. They seem emotionally better equipped than we are. If my marriage broke up, my wife could easily move in with a sister. I’d be as lost as plankton.

Later, I related my friend’s Yoko analogy to my wife. She pointed out that Ono and Lennon had a marriage based on what they both cared most passionately about, art—not money or sex, to judge from the fact that Lennon went off for a year with a mistress and the marriage survived. But how many of us can afford that? Tuten says that even the New York art world is short on mistresses. “Victor Hugo had a mistress even when he was in exile in Jersey. He lived in a house with his family and the mistress lived down the road, and he went to and fro. I don’t know anyone in the art world who has that. I don’t know too many men who have enough money to set up an apartment for a woman.”

Indiana University in Bloomington is known for its forested campus with a creek running through it and its attraction to great scientists, the most famous of whom was an insect man, raised in a repressive Methodist family, who broke away from the study of gall wasps in the forties to photograph human beings having group sex in his attic, thereby rehearsing what he would soon give all Americans permission to do in their own homes.

Today the institute named after him has a more holistic mission than the strict focus on the genital. It’s called the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction and occupies a cavelike set of rooms with only one doorway to get in to it in one of IU’s stately buildings. I sat down in Jennifer Bass’s office and saw a funny magnet on her file case, a photo of highway interchange signs on a downtown cloverleaf: NO SEX FOR A WEEK on one exit, NO SEX FOR A MONTH, FOR A YEAR.

We talked about a concept Bass had introduced me to, polyamory. She said, “The old open marriage has given way to this.” Polyamory is something of that fantasy I and other men I know harbor, of a community of free-loving people in multiple relationships. Not just dyads, or couples, but triads, or a woman with two “primaries,” a whole community of friends with benefits. “With practice, we can develop an intimacy based on warmth and mutual respect, much freer than desperation, neediness, or the blind insanity of falling in love,” Dossie Easton and Catherine A. Liszt, two former hippies, write in The Ethical Slut.

My most liberated male friend has expressed a similar view. He finds my confession of sexual torment backward. “It breaks my fucking heart to hear you talk that way. That any person has to talk about where their sexuality has led them in a shameful manner, in relation to other people. That a person’s sexuality has led them to hurt, and I don’t mean physically, another person— that breaks my heart.”

If we simply got rid of a vow of sexual exclusivity and the piety around “faithfulness,” which is a religiously inscribed misnomer for sexual exclusivity anyway, we have no idea what the family would look like in 100 years, he says. Okay, most people would be sexually exclusive and married. But there would be a party going on at the other end of town, in a community of people of high sexual desire who understood that about one another and didn’t feel jealousy or possessiveness.

I like the idea of going to that end of town, but I also wonder how much time it would take. Would my new relationships get complicated? Bass said, “One of the tenets of polyamory is that it is honest and consensual: This is something that’s out with your primary partner. How many people are willing to do that? It takes a lot of work. Because it’s about relationships, not about sex.”

Then she brought me downstairs to a seminar on images of prostitution. The institute takes a very nonjudgmental view of prostitution officially, but the visiting researcher on hand was negative about it. Sven-Axel Mansson had spent many years studying prostitutes in Sweden and argued that the desire of men for prostitutes had nothing to do with sexual “needs.” Rather, the drive is socially ordained: because men need to project their own sexual feelings onto a “dirty whore,” or because powerful men like Spitzer want to give up power for an hour or two.

The talk made me feel ashamed of my own fantasies. I had brought with me a printout of bloggings by Debauchette, a high-priced courtesan. Said to look something like a young but more bookish Demi Moore, Debauchette has obviously made a lucrative career of serving and tantalizing rich men, sometimes flying to Paris for threesomes in a sex club, thereby making Eliot Spitzer with his Amtrak-to-Washington fiddle seem unambitious. Debauchette described herself as a “highly sexual woman with a highly compartmentalized life,” and that fit right into my fantasy of the sort of demimonde that modern men and women might establish in respectable society. “He put it out there that he wanted a real relationship, something emotionally monogamous but sexually open, the sort of relationship I love best,” she wrote, and I only wondered if it was real. A commenter said he had gone into the Parisian sex club where Debauchette had been having a threesome, on a different night, and found the strobe room mostly devoid of women.

Erick Janssen is Kinsey’s lead researcher, and after the lecture, he took Mansson on. Prostitution, he said, “has to do with differences in sexual desire between men and women in general. I hate to stereotype anyone by gender. Unfortunately, there’s so much data to support the fact that, overall, men have a higher level of desire. Say if you look at masturbation frequency. If there’s a desire and no outlet, you’re going to find ways.”

Mansson seemed unconvinced. Later in his office he told me about what a dismal life prostitutes lead. “What I saw was actually misery. I saw the effect of this life specifically on women. The dark side of the forest. The negativity of being exploited, of being under the reign of the pimp. So as a result of that, I decided to launch a social-outreach program for people to exit prostitution.”

I asked Mansson about the implicit argument in Debauchette’s writings that prostitution can be legalized, dignified.

“I have a hard time from the research I’ve been doing to valorize this as a social institution … [But] I have met women who said that. Women who really think that they enjoy being prostitutes, being ‘sex workers,’ as they say. They would say, ‘I feel in command, I have determination over my life situation in a way I’ve never had it before. I’m loved by my customers.’ But these are the exceptions. They are not the main.” Had these women been given a choice, they would have chosen other things. “Because even among these women, you would find there it has a high cost. Problems with intimacy and sexuality after they quit their career. They dissociate their feelings in order to survive … The problem has been to make it whole again.”

I went on to Janssen’s office. There were pictures of erections on his wall and erotica. Janssen has tried to come up with a model for predicting who will cheat, based on two curves: one for sensitivity to sexual stimuli, the other a curve of risk-taking. These traits he calls rather prosaically “gas pedal” and “brake pedal,” though the questionnaire he offers touches on the tremulous drama of being a sexual person in an everyday world. Here are statements designed to measure sensitivity.

“When a sexually attractive stranger looks me straight in the eye, I become aroused … [Agree/disagree?]” “When a sexually attractive stranger accidentally touches me, I easily become aroused.” Even among people who would strongly agree with those statements, some are more capable of overriding those feelings. These are people with a strong awareness of risk, which Janssen measures with statements such as these: “If I can be heard by others while having sex, I am unlikely to stay sexually aroused.” “If I feel that I am being rushed, I am unlikely to get very aroused.”

I told Janssen about my friend’s comment: “There is no more unnatural principle of social organization than sexual exclusivity.”

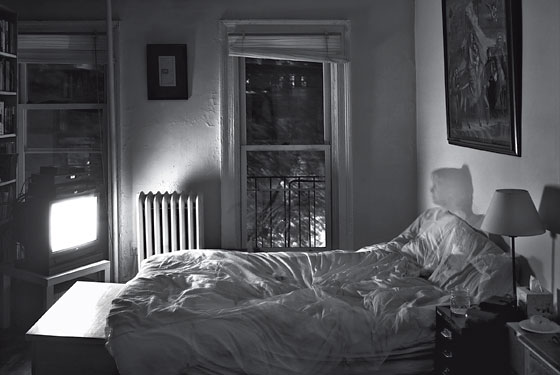

When I told my wife some of the ideas about about male sexuality, she got agitated. “Okay. Let’s have an open marriage,” she said, adding that she’d be spending the evening away on Wednesday. I said, No thanks.

Janssen made a face. “Infidelity is not just a social issue. It is a problem of trust and intimacy in a relationship. You have responsibility toward your partner. Why don’t men make sure they have open relationships? Let them be gutsy to stand up and tell their wives.” He shrugged. “If you can handle that—” I spoke of sexual passion and the way it makes social attitudes seem like so much debris on the ocean of real experience. A friend of mine was married for fifteen years to a woman with whom he came to understand he was incompatible, values-wise. Women had always flirted with him; finally, he made a date. “I thought the world was going to collapse when I did it,” he said. “When I was growing up, people would say they were such sinners they thought the church would collapse if they just walked inside. Well, it didn’t collapse.” He had complete pleasure; he could not accept that something that felt so good was wrong. His marriage broke up a year later, and then he met a nurse who also worked as an escort and who loved sex and loved the fact that he loved it. “Everybody’s different … She taught me I could have sex without a relationship. I didn’t want to talk to her, I didn’t want to go to the movies. I would knock on her door, and that was it. This went on for years.”

Janssen heard me out and nodded. “Underneath it all is this issue, if there is some divide between the sexes overall in how important sex is, how often you have it and with whom, and whether biological or not, how do we deal with that? We institutionalize things. We create institutions like marriage. For most people, it seems to work. That seems to be the issue we’re dealing with. Should that change?”

“Well, New York was just deprived of a really smart governor because he had a need for an illicit but consensual relationship,” I said.

“Consensual relationship, yes. But not to the person you’re cheating on,” Janssen said. “If indeed this is an essential part of you—”

“A friend calls it core.”

“Well, core could still be learned behavior. Essential means ‘part of my biology.’”

The distinction is crucial. Our core has many components, and even the evolutionary psychologists say that there is an evolved desire for pair bonding, for love.

The obvious question is whether we can import a European understanding. The stereotype is that in Europe, they have got this figured out, and every time they snigger over our scandals, they seem more superior. A gay friend tells me that gay European friends laugh at him because even gay relationships here tend to follow a bourgeois, monogamous model.

David Buss points out that in the U.S., it is very difficult for a candidate to be elected who has no professed religious belief, while this is not the case in Europe. In Germany, prostitution is legal. “It’s cleaned up and taxed, and the prostitutes get health insurance and benefits that they couldn’t get if it was illegal.” And German husbands and wives take separate vacations with the understanding that romance might ensue. “You could argue that European sensibility is more civilized and natural.”

I asked Glyn Vincent, a New York writer on social and cultural matters who is half-French, about norms.

“Marriage is more of a formality; sex is not the most important thing,” he said. “From the time I was small, I was led to understand that people have affairs. C’est la vie. This is just going to happen. You’re not going to make a big deal out of it when it does happen. You shouldn’t be hurtful about it. You’re going to be discreet. Don’t shove it in people’s faces.” While Vincent sees young Americans experimenting with new norms—“fuck buddies,” friends with benefits, etc.—those innovations don’t seem to have rubbed off on their elders. New York divorces continue to involve sexual infidelity as a breaking point. “When I make a comment about infidelity in social situations, there’s always a little element of mistrust in people’s eyes,” he said.

European norms may contravene some basic American ideals. In Mating in Captivity, Esther Perel, a New York therapist, says that “egalitarianism, directness, and pragmatism” are entrenched in American sex lives. Her point is seconded by two recently divorced women I know who describe their husbands’ promiscuity as “sociopathic.” In both cases, the men were closeted about their behavior, and the revelation of the secret was bone-crushing.

But Vincent says that French women have to “put up with a lot” and so too do those instinctual Italians.

“I’ve heard this mythology so many times, that Italian women, they’re more mature, more understanding of men’s needs, they expect infidelity. They don’t complain,” says Tuten, who was married to an Italian woman. “I don’t know if it’s true. A lot of Italian women expect their husbands to turn into philanderers, and how do they live with it? Some live by suffering.”

Why can’t we shift American norms? We’ve transformed attitudes about premarital sex and homosexuality in the last 40 years. Why not actively change the rules here and let men and, yes, women too do what they want?

Vincent’s answer echoed the sympathy I’d seen for Mansson’s point of view at the Kinsey Institute.

“I think we’re getting into a question of social stability. The male libido is considered a very dangerous and a potentially disruptive force in society. I think that’s why there are so many religious dictums and taboos around that. The idea that one is allowed multiple partners—this is something that has to be rigidly controlled.”

David Buss also spoke of the libido’s lash. “We understand that infidelity is a great source of stress and conflict and causes a lot of marriages to break up when discovered. It causes a great deal of anguish. The Jimmy Carter model might be better. Lust in their hearts.” This is obviously an American norm. “There’s a lot more fidelity than infidelity,” Bass says. Even if adultery is underreported, as seems likely, studies show that about 25 percent of married men commit adultery, 15 percent of married women.

Nonetheless, the one strong impression I took away from interviewing peers is that American mores are evolving, especially among the affluent. An affair or two is handleable for the rich, says a friend, Jo Mango. “They’re more well read, better informed, and more tolerant. They say, ‘Get over it.’ It’s way costlier to break up. Because look what happens: You lose your living situation and your community in a divorce.” A sophisticated New Yorker made a similar point: “I don’t believe that straying diminishes your love or commitment to your partner. It’s not a zero-sum game. However, it does get complicated and hurtful when you start developing an emotional relationship with another woman.

“But it’s between the partners. Look at all the accommodations you make in a marriage. It’s individualistic. I actually think that we have made a lot of progress publicly about this.” He was referring to the Clintons, and maybe the Spitzers too. They’d been humiliated in the public square, but they’d survived it, so far. Their marriages were formal and more broadly based than their sex lives. Bill Clinton has himself pointed to the Roosevelts’ highly layered marriage as a model. So does my oldest sister. She’s true blue in her marriage, and I had expected her to be moralistic about cheating. But she says that documentaries she’s seen on the Roosevelts and all the science about homosexuality has made her shrug—about others, that is.

Ever since the sexual revolution began, dreamers have made prodigious efforts to normalize infidelity, to bring that paradisiacal planet in their minds into the ordinary world. In Thy Neighbor’s Wife, published in 1981, the prominent journalist Gay Talese got his mind blown at Sandstone Retreat, a communal retreat in the Santa Monica Mountains, outside Los Angeles, led by a charismatic man named John Williamson. It reminded Talese of Oneida and earlier American experiments in communal eroticized living, and he tried to sell it as the latest twist in a road that had begun with Hugh Hefner. But Talese’s version wasn’t convincing. The experience strained his own marriage, and life in the commune was pretty stressful. One of the husbands, still holding a day job at New York Life, said that Williamson had set it all up to give himself access to other men’s wives.

The same sordid air hovers over The Blood Oranges, by the late John Hawkes, another American novelist’s fantasy of liberated sexuality, set in a utopian Mediterranean setting called Illyria. Led by the “sex-singer” Cyril and his panty-dropping wife Fiona, two couples try to make openness work, but both end up smashed, one forever, by a suicide. Lately, the novelist Scott Spencer, who first gained notice in the seventies with the adolescent fantasy of burning desire, Endless Love, published a novel, Willing, about the ultimate male fantasy: men running away from sexless, high-pressure, Ambien-pacified life in the U.S. for sexual tourism with “body workers” in Scandinavia. It turns out to be a big downer. “Prostitutes are like psychiatrists, ambulance drivers, tutors and personal trainers; they’ve got to be used to human wreckage,” Spencer writes.

When I got back from the Kinsey Institute, I told my wife all about the evolutionary data and Erick Janssen’s questionnaire, and she got agitated. “Okay. Let’s have an open marriage. And I have to be out Wednesday night.”

I said, No thanks.

I talked about my failure to grasp the nettle with a couple of other men. “When we were kids, we thought we were going to grow up and be mature; we’re not going to be crazy kids,” Tuten says. “But these questions, they never have an answer or a terminal point in age. We’re crazy all the time, we’re burning all the time … When you’re in love, you’re jealous. I’m in love with a woman, she has an affair, my heart is broken. I become ill. I can’t bear it. When you’re not in love, everything is permitted.”

A gay friend who has “brooded” over his infidelity for a long time, sometimes feeling that he ought to confess, told me it’s a very 17-year-old American view of the world to think that you should tell someone you love everything and somehow the world will be a better place. Instead, he reminds himself, he’s a grown-up, he has secrets.

He’s keeping those secrets to protect himself as much as his mate. “A relationship is a myth you create with each other. It isn’t necessarily true, but it’s meaningful. The key to that myth is that the other person is enough for you. You know in your head that another person isn’t enough for you. But if you don’t honor the myth, then it crumbles.”

How’s that for a happy ending?

A 401-Person Poll