It’s a massive understatement to say that the full story of Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl’s capture by the Taliban, five years in captivity, and release over the weekend is still unknown. That’s part of the reason why the conspiracy theories are flying. Given the research into prisoners of war and other situations, however, we can develop an early, sketchy sense of what he went through — and the obstacles he faces now that he’s free.

Two items from the literature are very helpful here: “The Prisoner of War,” a chapter written by Robert J. Ursano and James R. Rundell that appears in the textbook Wartime Psychiatry, and “Hostage-Taking: Motives, Resolution, Coping and Effects,” a paper by David A. Alexander and Susan Klein that appeared in Advances in Psychiatric Treatment.

Based on this research, here’s what we can say with some certainty:

1. The fact that Bergdahl was a sole captive probably made things a lot harder on him. Ursano and Rundell write that “Probably the single most important adaptive behavior in all POW situations is communication.” POWs in Vietnam, they explain, developed elaborate tapping codes to communicate with each other when doing so verbally was impossible. Moreover, they explain, among people who have lived in isolated conditions in the Antarctic, social concerns pertaining to isolation were “more significant than coldness, danger, and other environmental hardships in determining psychological adjustment.” It’s no stretch to apply this to POWs as well — humans rely on social interaction to keep them sane and healthy, whatever the circumstance (that’s part of the reason some people consider solitary confinement to be torture).

This doesn’t bode well for Bergdahl, of course, since he was captured alone. But even social interaction with the enemy is social interaction, so the amount of time he spent isolated from his captors may go a long way toward determining the ease of his readjustment.

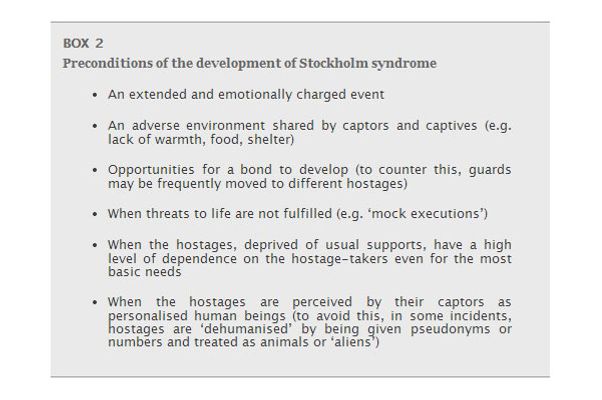

2. Bergdahl may have developed some Stockholm syndrome, and you shouldn’t blame him if he did. Alexander and Klein are reluctant to call Stockholm syndrome a “syndrome” at all, given that “it could be reasonably argued that the behaviour and attitudes associated with this reaction are normal in response to an abnormal event and can be adaptive.” That is, captives may have a better chance of surviving if they make nice with their captors, so it can be the strategically sound psychological defense mechanism. Moreover, the authors point out that some researchers “have suggested that [Stockholm syndrome] is the product of reporting and publication bias by the media.”

That said, it’s clear that a lot of captives do end up identifying with their captors, and the researchers list six conditions that make this more likely to happen:

Based on what little is known of Bergdahl’s captivity, it would appear that most of these apply.

3. His return will be particularly difficult because so many people are questioning the circumstances of his disappearance. Ursano and Rundell note:

The repatriated POW emerges from what is likely to be a prolonged period of emotional blunting, monotony, apathy, withdrawal, and deprivation, into a rapidly paced series of medical evaluations, family reunions, and public relations activities. The brief period of euphoria upon release is quickly replaced by a period of overstimulation.

The problem is compounded by the fact that most POWs “have had little experience dealing with the media,” meaning they can make life-altering blunders if a camera is shoved into their face during a very vulnerable period. That’s why it’s important, the authors write, that repatriated POWs be shielded from the media and offered training in how to handle it when they get home.

For Bowe, this is all doubly true — he’s going to face an unprecedented level of scrutiny as a result of the anger some have expressed at the murky situation surrounding his disappearance (it’s been reported he intentionally wandered off his base), and the fact that several of his colleagues died during the subsequent search for him.

-

What’s surprising, in light of the traumatic nature of these sorts of events, is how often released prisoners of war are able to successfully readjust. Ursano and Rundell note that “most former POWs readjust without clinically significant pscyhopathology,” and that many of them “report that they benefited from captivity, redirecting their goals and priorities and moving toward psychological health.” Bergdahl’s case is of course a bizarre one even by the standards of wartime captivity, so perhaps his readjustment will be particularly troubled as a result. But the research suggests that humans do have the psychological tools to move past these experiences without enduring permanent psychological damage.