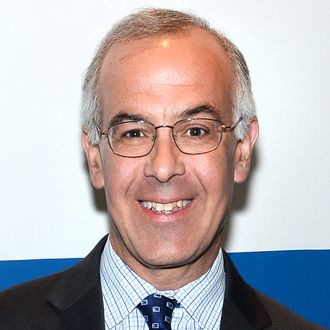

Yesterday, David Brooks published a column that boiled down to, “Chill out — things aren’t so bad.” Despite the horrible news we’re pummeled with every day, he argued, when you zoom out, the country and the world are on the upswing:

The scope of the problems we face are way below historic averages. We face nothing like the slavery fights of the 1860s, the brutality of child labor and industrialization of the 1880s, or a civilization-threatening crisis like World War I, the Great Depression, World War II or the Cold War. Even next to the 1970s — which witnessed Watergate, stagflation, social decay and rising crime — we are living in a golden age.

Our global enemies are not exactly impressive. We have the Islamic State, a bunch of barbarians riding around in pickup trucks, and President Vladimir Putin of Russia, a lone thug sitting atop a failing regime. These folks thrive only because of the failed states and vacuums around them.

Sure. It’s an argument that makes some sense, and one that Steven Pinker laid out in depth a few years ago in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature.

Brooks’s diagnosis as to why there’s such a widespread sense of dread, though, misses the mark:

It’s important in times like these to step back and get clarity. The truest thing to say is this: We are living in an amazingly fortunate time. But we also happen to be living during a leadership crisis, and a time when few people have faith in elites to govern from the top. We live in a vibrant society that is not being led.

We don’t suffer from an abuse of power as much as a nonuse of power. It’s been years since a major piece of legislation was passed, and there’s little prospect that one will get passed in the next two.

Brooks is suffering from a version of the so-called “curse of knowledge” here — a psychological tendency to assume that because you know something, everyone else does, too. Being a politically inclined columnist, he’s grimly aware of the fact that Washington is currently being run like a severely mismanaged Arby’s franchise. But are Americans really tracking the progress (or lack therefore) of legislation that closely?

Yes, approval of Congress is at a historic low, but how far can that really go in explaining why people are freaked out about ebola or ISIS? Plus, a lot of research suggests that Americans are pretty shaky when it comes to the specifics of governance, that they don’t sit around pondering weighty Brooksian questions about the nature and legitimacy of elite authority.

So there are other, more straightforward reasons for all the negativity:

1. People are hard-wired for it. We are a skittery species, and we tend to focus on the negative. All things being equal, we’ll always be more captivated by bad news than good news, by the threat of losses than the promise of gains. While there are of course long-term trends when it comes to overall levels of public optimism — sometimes upward, sometimes downward — there will always be a sizable minority of people arguing that something — kids these days, American foreign policy, environmental degradation — is as bad as it has always been. Our brains can’t resist it.

2. Politicians will alway harp on negatives. Partly because of (1), lawmakers generally don’t get elected to office or drum up support for legislation by delivering lengthy speeches about how wonderful everything is. Rather, they score points by pointing out everything that’s gone wrong and how you can fix it. Thanks to this, it’s easy to think that whatever’s happening now or has happened recently is the Worst Thing Ever. That’s why most Americans think either Barack Obama or George W. Bush is the worst president ever.

3. We have more access to Horrible Things than ever before. As I noted a few weeks ago, we’re living out a giant experiment when it comes to exposure to gruesome, horrible news. At any given moment, you’re just a few clicks or taps from summoning ISIS’s most horrifically violent acts onto the screen of your choice. Plus, thanks to (2) and the extremely polarized nature of our media-consumption habits, it’s easier than ever to internalize politicized doom-and-gloom messaging. Could all this, in the long run, to view the world more negatively than they would otherwise? We don’t know yet, but it’s certainly a reasonable question.