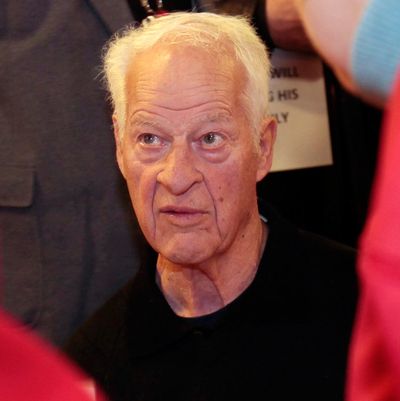

If you want an inspiring modern medical-miracle story, the family of Gordie Howe — a.k.a. Mr. Hockey, one of the greatest NHL players of all time — has got one for you. The 86-year-old Howe suffered a stroke in October, and for the following two months he was not in good shape. Things only got worse in early December, when he was admitted to the hospital for what was initially reported as another stroke but was probably dehydration.

Then, as the Howe family recounted in a statement it released later that month, a company called Stemedica Cell Technologies got in touch. Stemedica, a San Diego–based manufacturer of allogeneic adult stem cells — stem cells that come from a donor rather than an embryo — “generously facilitat[ed] Dad’s participation in a stem cell clinical trial at Novastem, a licensed distributor of Stemedica’s products in Mexico.” Howe went down to Mexico and received treatment on December 8 and 9 — “neural stem cells injected into the spinal canal on Day 1 and mesenchymal stem cells by intravenous infusion on Day 2,” as the press release puts it.

This is where things get murky. To Howe’s family, the results were miraculous. The hockey great, who had been suffering from all of the indignities and disabilities one would expect to find in an 86-year-old recent stroke victim, almost immediately took to the treatment, according to the release:

At the end of Day 1 he was walking with minimal effort for the first time since his stroke. By Day 2 he was conversing comfortably with family and staff at the clinic. On the third day, he walked to his seat on the plane under his own power.

By Day 5 he was walking unaided and taking part in helping out with daily household chores. When tested, his ability to name items has gone from less than 25 percent before the procedure to 85 percent today. His physical therapists have been astonished. Although his short-term memory, strength, endurance and coordination have plenty of room for improvement, we are hopeful that he will continue to improve in the months to come.

“As a family, we are thrilled that Dad’s quality of life has greatly improved, and his progress has exceeded our greatest expectations,” the family wrote.

To various stem-cell experts, though, there are numerous red flags here suggesting the story is, in fact, too good to be true. And they’re worried that the public excitement over Howe’s ostensible recovery, which has included extremely credulous coverage, up to the level of a TV segment in which an exceedingly credulous Keith Olbermann interviewed Stemedica CEO Maynard Howe (no relation to Gordie), could lead desperate families to spend large amounts of money on forms of treatment that have not been proven to be effective.

“This seems to be a lot about hype for the company, and it’s an anecdotal sample size of one story, which is really hard to interpret,” said Dr. Jack Parent, a professor of neurology at the University of Michigan Medical Center and staff physician at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Parent, who has a decade’s worth of experience researching the role of adult stem cells in epilepsy and stroke, said that neither of the two days of treatment consisted of anything that has been shown to be effective in stroke patients.

On the first day, neural stem cells were injected into Howe’s spinal canal, the idea being that those cells would then be delivered to the site of the injury to Howe’s brain. Injecting the cells directly into the spinal fluid would allow them to bypass the blood-brain barrier, which would otherwise prevent them from getting into the brain, but Parent doubted that would be enough for them to actually perform the regenerative work Novastem is claiming. “I am skeptical that enough of the cells make it to the brain from the bottom of the spinal column, penetrate into the substance of the brain itself. and survive for any significant length of time,” he said.

As for the mesenchymal stem cells that were injected intravenously during the second day, Parent said that others have tried this as a means of stroke treatment. “These are a type of adult stem cell that have been studied quite a bit over the years, and there are other clinical trials in stroke with these stem cells,” he said, “and they are purported to act not by replacing damaged brain cells but by providing growth support for the existing cells to try to repair as much as possible.” The problem, though, is that this just hasn’t shown all that much potential. “None of the trials have been particularly exciting with that therapy.”

Parent is far from the only medical expert to express skepticism about the Howe story. Paul Knoepfler, a stem-cell expert and medical blogger, highlighted the various strange aspects of the Howe family’s press release, while David Gorski, another medical blogger who’s an oncologist, wrote two extremely comprehensive posts for Science Based Medicine running down questionable aspects of the recovery timeline, the companies in question, and a variety of other issues.

The posts themselves do a very good job explaining the complicated details here, and it’s worth rehashing them in full. But in short, to believe that Howe’s stem-cell treatment worked, you have to believe that a Mexico-based company whose doctors have no specific training in stem cells (as per Gorski’s first post) were able to successfully treat a patient using a regimen that has no real scientific evidence behind it. You have to ignore the shadiness of talk of Howe participating in a “clinical trial” when — again, as per Gorski’s research — there’s no clinical trial going on in the U.S. for which he would have been eligible. You also have to ignore the shadiness of a company whose treatments cost in the range of $20,000 offering free treatment to a high-profile patient, and that patient’s family then bringing extensive free publicity to the company in return. It’s a story that sounds sturdy at first glance but starts to wobble a bit when you apply even a gentle poke of skepticism.

People, including members of the media who know better, are ignoring all of these red flags, of course. It’s simply too good a story — who wants to be the buzzkill prattling on about a lack of randomized controlled experiments or who drowns readers in the details of how mesenchymal stem cells work?

There’s also the influence Murray Howe, Gordie’s son and a radiologist in Ohio, has had in shaping the narrative. Howe, based on public statements he’s made and a conversation I had with him a couple of weeks ago, seems genuinely convinced that the treatments worked. “Every day we see little new lights of promise,” Howe told me. “He basically improves a little bit more every day, and it just continues to surprise us.”

According to Howe, these days, when his father isn’t helping around the house, he’s practicing stickhandling in the driveway of his daughter’s home in Lubbock, Texas, where he lives. He’s off all of his sleep and anxiety meds. “He’s almost like a teenager who is growing rapidly and kind of gaining new tissue, because he’ll just sleep like Rip Van Winkle for a good 13 hours,” said Howe. “He’s also eating a huge amount — he’s eating, like, twice his normal amount because it just seems like his body’s in repair mode. He’ll wake up after the 13 hours and he’ll just have a robust breakfast.”

“I would say he’s basically back to where he was before he had his stroke,” said Howe, “and we’re hoping for continued improvement so that even some of his dementia symptoms will continue to improve, so we may end up having him be stronger than he was before the stroke.” Howe is still a fall risk who needs someone nearby when he walks, his son said, and like other elderly people with dementia he’s sometimes more “there” than at others. And long-standing memory issues linger, especially when it comes to short-term stuff like remembering what he had for breakfast.

There’s a lurking possibility here that isn’t fun to think about. Maybe the improvement Murray and his family are seeing doesn’t have anything to do with the stem cells but is rather the result of a combination of the natural recovery some people experience after a stroke and the by all accounts very good, very comprehensive care Howe’s family is providing for him (as Murray explained, Gordie has regular appointments with a speech therapist, a physical therapist, and an occupational therapist).

To Parent, the University of Michigan neurologist, this theory makes sense. “There are other reasons for people to get better,” he said. “There are placebo effects, there is concurrent medical care where when you’re treating someone you’re making sure they’re hydrated and they’re taking their other medicines appropriately and things like that. So you really need a control to be able to tell whether the effect you see is really from the treatment or not.”

When I asked Murray whether he thought this was a possibility, however, he wasn’t having it. “Not at all,” he said. Murray explained that while the stroke initially almost totally immobilized his father and more or less paralyzed his right side, there was, over time, slight improvement as he regained some basic functionality. This was followed by a setback, though, “basically … to the point where he was bedridden” — the episode that culminated in his admission to the hospital for what was likely dehydration.

“From December 3 until we got him to San Diego, there was no improvement — there was really just a gradual downturn during that time.” Murray insists that until the time the family took him to Mexico, things remained dire, and it was only after the stem-cell treatment that the current trend of recovery began. “Anybody that says, ‘Oh, this is just a natural progression or improvement from a stroke,’ you know, wasn’t there to see what his baseline was” before the treatment. “The fact that he was actually standing and walking eight hours after the intraspinal injection — there’s nothing that can explain that short of responding to the cells.”

Murray’s excitement is infectious; just witness the embarrassing Olbermann segment, in which it’s blindingly clear how badly the host wants to believe, not to mention the countless other skepticism-free write-ups carried by various news organizations. But the desire to believe in a good story can only take us so far. We don’t have any sort of independent verification of the claims being made by the Howe family. And the nuts-and-bolts side of medical research is, by design, as coldly data-driven as possible — precisely so human tendencies, like our understandable desire to see our parents — not to mention our sports idols — remain as healthy as possible for as long as possible, don’t color our assessments of what does and doesn’t work.

There’s a chance everyone will learn at least a little bit more about Gordie Howe’s state soon; he’s scheduled to appear with Wayne Gretzky at an event in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, on February 6 (Murray said in an email he sent me a week ago that the plan is still for his father to attend). That won’t be enough to make a scientific assessment of his progress, of course, so this story is going to remain mired in uncertainty for the foreseeable future. What’s perfectly clear, though, is that while experts continue to debate this strange late chapter in Gordie Howe’s life story, anyone with $20,000 or so can call up Novastem and see about bringing their ailing loved one down to Mexico for treatment.