This year, kids at a New York City elementary school saw one of their greatest wishes granted: P.S. 116 in Kips Bay abolished homework. Or, more precisely, the school’s administrators abolished traditional homework, like take-home worksheets, instead encouraging students to do things like have dinner with their families, read, or play outside in a park. You know — fun things.

Many P.S. 116 parents subsequently, and perhaps predictably, freaked, especially after reading conflicting media reports about the policy change. “People who were confused about it read these reports, and then were even more confused,” said Simone Levin, co-president of the PTA at P.S. 116, who has the unenviable job of explaining the change to parents at her school. One father of a second-grader at the school told DNAinfo last week that he was already looking for another school for his daughter; another dad told the site he’d continue to assign his third-grade son extra homework of his own creation.

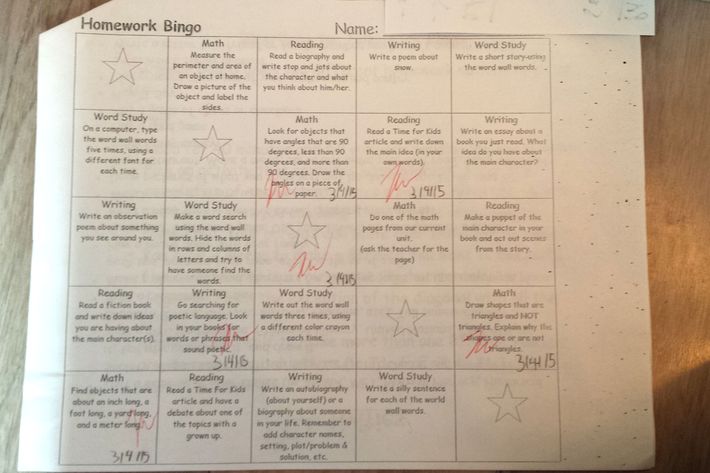

What does the new policy entail? Basically, students are given bingo-style sheets with a number of assignments — both nonacademic stuff like sitting down to a family dinner and academic stuff like measuring the dimensions of the room they’re in — they’ll have to complete during the week. The rules are different for different grades, but, basically, the kids get to choose which assignments they complete, as long as they get through a certain number of them. The tasks are time-bound, not completion-bound, meaning that the kids are only instructed to spend, say, 20 minutes on a task and then move on, whether or not it’s done.

It’s certainly an unusual approach, but research suggests that the educators at P.S. 116 might be onto something here. Decades of scientific inquiry into the link between homework and academic achievement (usually measured by test scores) suggests that, at least for elementary-school kids, the association is a murky one, at best. “There’s no strong evidence supporting homework in the elementary grades,” said Tom Loveless, senior fellow for the Brown Center on Education Policy and the author of a comprehensive 2014 report on education in the U.S. that focused on homework. “But there’s no strong evidence that it’s harmful either.” (High-school and middle-school kids, most researchers agree, do benefit from a moderate amount of homework.)

Doing one’s homework on elementary-school homework is somewhat dizzying, but here’s a brief review of some of the best reviews I came across:

- According to a 2006 review of the research led by Duke University’s Harris Cooper — considered by many to be the preeminent expert on homework and academic achievement today — the results of 69 studies show only a weak correlation between homework and academic achievement for the elementary grades.

- But an earlier analysis of 15 studies, published in 1984, suggested that homework did have a positive impact on successive academic achievement for fourth- and fifth-graders.

- In a brief 2012 textbook chapter reviewing the research, Jianzhong Xu of Mississippi State University once again searched for a link between homework and academic achievement, and found “no linkage at the elementary-school level,” he said in an email.

The literature goes on like this; for every study claiming homework does, in fact, lead to better grades for elementary-school kids, another declares the opposite. But that conflicting evidence hasn’t prevented elementary schools from increasingly piling on the worksheets in recent years: Loveless’s report found that the number of 9-year-olds assigned no homework fell 13 percent since the mid-1980s, whereas the workload stayed steady for 13- and 17-year-olds. (The general consensus about appropriate homework quantity, incidentally, is about 10 minutes per grade level — so a second-grader shouldn’t have more than 20 minutes of homework a night, and so on.)

That doesn’t necessarily mean assigning homework to younger kids is always a bad idea, or a waste of their time, though. For younger kids, the benefits of homework extend beyond academics.“Homework appears to provide more academic benefits to older students than to younger students, for whom the benefits seem to lie in nonacademic realms,” write the authors of a research review published by the Center for Public Education, an entity run by the nonprofit National School Boards Association. For example, Xu found in a 2004 study he co-authored that homework helps third-graders learn self-discipline and time-management skills. Other researchers have found that homework builds a foundation of strong study habits and the ability to learn independently. So, for younger kids, the point of homework may not be so much about the assignment itself, but about the routine and the habits that completing the assignment creates for the kids.

After reviewing this research, P.S. 116 administrators decided there was no real evidence binding them to the worksheet model of homework. “Our thinking was, if there’s nothing that can make a definite connection between academic achievement and traditional homework assignments — why are we continuing to just give it? Simply because it’s always been done?” said P.S. 116 assistant-principal Gary Shevell who was part of a team of educators and administrators who spent a year reviewing the scientific literature regarding elementary-school homework.

The new assignments, on the other hand, are designed to nudge the kids into activities that do have solidly proven benefits, Shevell said. The ritual of family dinners, for example, has been linked to a variety of benefits for kids, including academic achievement. Another task that may appear on a bingo sheet is to play in a park — and a Pediatrics study last fall suggested that outdoor play leads to improved cognitive performance in elementary-aged kids.

It’s not exactly a sweeping trend for schools to abandon traditional homework the way P.S. 116 has, but in 2012, Gaithersburg Elementary near Washington, D.C., made a similar move. Now, the only homework students receive is 30 minutes of reading per night. It’s too early to tell what the results of principal Stephanie Brant’s experiment will be, but Brant told me that according to school records, 84 more students (out of about 800) are reading at their appropriate grade level as compared to last year’s data.

Brant remembers the overwhelming amount of feedback from parents and the press she received when her school made the switch, and said she has considered emailing the administrators at P.S. 116 to tell them, “I promise you, it’s going to calm down.”

Although the hand-wringing over homework has the feel of a singularly modern problem, it isn’t. Educators and parents have been arguing over homework for at least a century, and the debate might actually have become less hyperbolic over time. It’s difficult, for example, to match the outrage of Jay B. Nash, a New York University physical education professor, who in 1930 thundered that “for the elementary school child and the junior high child” homework is “legalized criminality.” I expect kids attending less experimental elementary schools than Gaithersburg and P.S. 116 will agree.