It doesn’t feel good to fake who you are, and an increasing amount of psychological research is showing how — and why — it hurts. Back in April, for example, Melissa Dahl reported on interesting new research, which suggested that faking your personality at work could lead to “burnout and perhaps even physical health consequences.”

It’s an area of fairly active research, particularly among social psychologists. They’re intrigued by the ramifications of suppressing emotional responses, in particular, because so much of human social life — and therefore human life — comes down to the subtle ways we react, mirror, and respond to each other’s emotional cues. Suppressing emotions, and therefore these cues, throws a bit of a wrench in the finely tuned cognitive systems we’ve evolved to interact with and support one another through. As far as researchers can tell, this sort of suppression can have negative effects on both ongoing relationships and first impressions.

In an interesting new study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Allison M. Tackman and Sanjay Srivastava of the University of Oregon sought to better understand the ways emotional suppression might affect first-impression judgements. “The background and motivation for our study was that previous studies, going back a while now, have shown in various ways that people who use expressive suppression experience social costs,” said Srivastava in an email. “They have less social support, less satisfying social lives, and they experience trouble getting close to others. So the next question is, why — what is going wrong?”

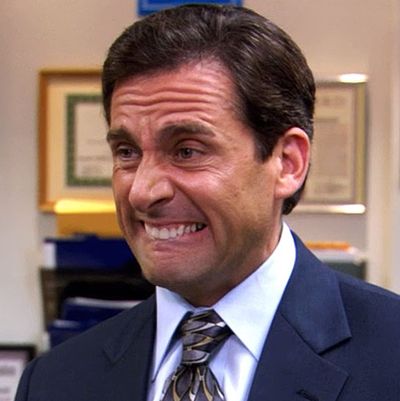

To better understand this phenomena, the researchers videotaped four individuals watching the funny, famous fake-orgasm scene from When Harry Met Sally and a sad scene from the 1979 film The Champ. Sometimes the actors were told to react naturally to the scenes, and sometimes they were told to suppress their reaction. The participants in the study, 149 undergraduates, then watched all four versions of the video without audio (having been told to observe the subjects carefully), and were randomly assigned to either a “context” condition in which they could see what the person in the video was reacting to, or a “no context” condition in which they couldn’t:

“After watching each video, participants reported their judgments of the target’s emotion experience, personality judgments of the target, and interest in affiliating with the target,” the researchers write, as well as answering a bunch of other items. Overall, the suppressors were judged to be less extroverted, less agreeable, and more “avoidant in close relationships” — more distant, basically — than the non-suppressors. Suppressing also had a “large effect,” as the researchers put it, on the participants’ desire to affiliate with suppressors as compared to non-suppressors — they found them much less likable.

“What we found, in a nutshell, is that other people judge suppressors to be low in extraversion and low in agreeableness,” said Srivastava. “Or in more everyday language, they seem like the sort of people who are socially distant and indifferent to others’ feelings. And those impressions help explain why others don’t want to get close to them.”

There was at least one possibly noteworthy exception, though, to the general suppression-is-bad story: Folks who watched the orgasm scene, but for whom the study participants could see what they were watching, were viewed as more polite than those who didn’t stifle their laughter, apparently because of the clip’s racy content (in the non-context condition the participants had no way of knowing what they were suppressing amusement at).

“This suggests that suppression may sometimes have positive effects, and in the future it would be interesting to examine other circumstances in which suppression is socially beneficial (rather than socially costly),” said Tackman. “In contexts where suppression is a normative response or socially appropriate, what kinds of impressions do people form of the suppressor’s personality?”

In other words, there are common-sense reasons to think that suppression is sometimes a good thing — maybe “when you’re with certain people,” as Srivastava put it, “or when you’re in certain social roles, or when you have certain goals.” Suppressing emotion, after all, pops up in all sorts of wildly different cultures — it’s something humanity does quite frequently. Finding out why, and when this behavior is beneficial, is the next step.