The conversation about racial disparities in Americans’ health outcomes has tended to focus on how adverse social and economic conditions depress life expectancy among African-Americans and Hispanics. But a new study co-authored by a Noble Prize–winning economist reveals an unprecedented public-health crisis concentrated within white America.

According to the report, an epidemic of drug abuse and despair has killed so many white middle-aged Americans over the past decade, the demographic has actually seen an increase in its mortality rate over the period, even as medical advances decreased the death rate across every other racial and ethnic group.

The spike in mortality was borne entirely by the white working class — the death rate for non-college-educated white men and women, ages 45 to 54, increased by 22 percent between 1999 and 2013, according to the new statistical analysis by the Princeton husband-and-wife economist team Angus Deaton and Anne Case. Prior to 1999, the mortality rate within that group had been falling steadily for decades.

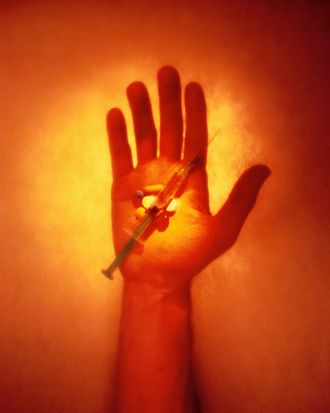

Over the past 15 years, the rate of death from strokes, heart disease, and cancer declined across the U.S. population as a whole. But that same period saw a profound uptick in self-reports of chronic pain and mental distress among white middle-aged Americans — particularly those without a college degree. The increased mortality within that demographic appears to be driven by maladaptive attempts to escape physical or psychological pain — the analysis documents an unprecedented increase in the group’s rate of suicide, alcoholic liver disease, and overdoses from heroin and prescription opioids.

The report itself offers no definitive explanation of the phenomenon it documents. However, the story appears to be, at least in part, an economic one. As the New York Times notes, inflation-adjusted income for households headed by a high-school graduate fell by 19 percent over the period studied. Still, a purely economic analysis cannot explain the racial dimension of the crisis. While middle-aged African-Americans still have a higher mortality rate than whites, their death rate nonetheless fell during the same period. In a commentary published alongside the study, Dartmouth economists Ellen Meara and Jonathan S. Skinner speculate that one source of this racial disparity may lie in the higher rate of prescription opioid use among white Americans.

A recent study in the journal JAMA Psychiatry sheds some light on the racial dimension of opiate addiction: It found that over the past decade, 90 percent of Americans who tried heroin for the first time were white, while three quarters said they had become interested in heroin after using prescription painkillers.

Whatever its cause, the explosion in the mortality of white middle-aged Americans is a public-health crisis with few precedents in modern times. The Washington Post suggests that the stark increase in the death rate of Russian men after the fall of the Soviet Union may be the closest historical parallel.

But in the scale of its devastation, the epidemic of drug abuse and suicide within the white working class reminds researchers of the HIV crisis of the 1980s. Had the mortality rate for white middle-aged Americans remained on the steady downward course it was charting in 1999, a half-million more people would be alive today. “Half a million people are dead who should not be dead,” Deaton told the Post. “About 40 times the Ebola stats. You’re getting up there with HIV-AIDS.”