Schizophrenia is a devastating and often destructive mental disorder, one that overtakes a young mind and sends it spinning out of touch with reality. About one in 100 Americans is estimated to have schizophrenia, and although the word itself has been around for just over 100 years, the illness has likely haunted humanity for thousands. The disorder tends to run in families, so scientists have long suspected a genetic component — and yet years of research since the first human genome was sequenced yielded no firm evidence of its root cause.

Until, that is, this week. In a landmark paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature, a team of the nation’s top scientists say they have pried open the “black box” of schizophrenia, pinpointing the genetic root of the disorder. “I’m a crusty, old, curmudgeonly skeptic,” Steven Hyman, the director of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at MIT’s Broad Institute, told the Washington Post. “But I’m almost giddy about these findings.” It’s a crucial first step that, these scientists say, may one day lead to earlier detection of the disease and more sophisticated treatments.

According to these new findings, a genetic stamp that people with schizophrenia inherit causes a normal process of brain development called synaptic pruning to go haywire, something some scientists already had a hunch about by comparing schizophrenic brains against typical ones. Let’s back up for a moment: In a baby’s brain, an incredible number of neurons and synaptic connections form — sometimes up to 40,000 per second. By toddlerhood, the brain has amassed more neurons and synapses than it needs, so the excess ones are eliminated; this process begins in early childhood and is completed by early adulthood.

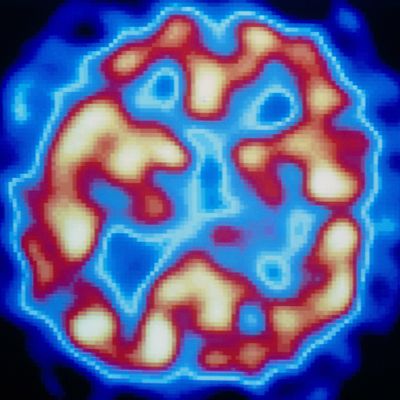

In a typically developing brain, this pruning process helps speed up cognitive functioning. But the schizophrenic brain takes this too far, eliminating too many of those neurons and synapses. “Normally, pruning gets rid of excess connections we no longer need, streamlining our brain for optimal performance, but too much pruning can impair mental function,” said Thomas Lehner, the director of the office of genomic research coordination at the National Institute of Mental Health, in a statement. “It could help explain schizophrenia’s delayed age-of-onset symptoms in late adolescence/early adulthood and shrinkage of the brain’s working tissue.”

Research has found, for instance, that certain brain regions in people with schizophrenia contain fewer synaptic connections, as compared to the brains of people without schizophrenia. Now this new genetic discovery may help explain why. As Post writer Amy Ellis Nutt explains:

In patients with schizophrenia, a variation in a single position in the DNA sequence marks too many synapses for removal and that pruning goes out of control. The result is an abnormal loss of gray matter. The genes involved coat the neurons with “eat-me signals,” said study co-author Beth Stevens, a neuroscientist at Children’s Hospital and Broad. “They are tagging too many synapses. And they’re gobbled up.”

For their paper in Nature, the researchers analyzed the brains of 700 people who’d had schizophrenia and donated their brains to science when they died. They also examined data pulled from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, which included more than 65,000 people — about 29,000 with schizophrenia and 36,000 without — from 22 countries across the globe. The team of scientists also studied the brains of mice to pinpoint the C4 protein, which “tags a synapse for pruning by depositing a sister protein in it called C3,” according to the NIH. “Again, the more C4 got switched on, the more synapses got eliminated.”

All of this is, of course, hugely exciting for anyone who has schizophrenia or loves someone with the disease. “Future treatments designed to suppress excessive levels of pruning by counteracting runaway C4 in at risk individuals might nip in the bud a process that could otherwise develop into psychotic illness,” again according to the NIH statement. “And thanks to the head start gained in understanding the role of such complement proteins in immune function, such agents are already in development.”

But scientists, being scientists, recommend caution for now. New treatments, or early detection and intervention methods, are likely still “decades” away. “We’re all very excited and proud of this work,” Eric S. Lander, the director of the Broad Institute at MIT, told the New York Times. “But I’m not ready to call it a victory until we have something that can help patients.” New interventions — much less a “cure” — for schizophrenia may not be right around the corner, but thanks to this new discovery, they’re now possible in a way that was unimaginable just a few years ago.