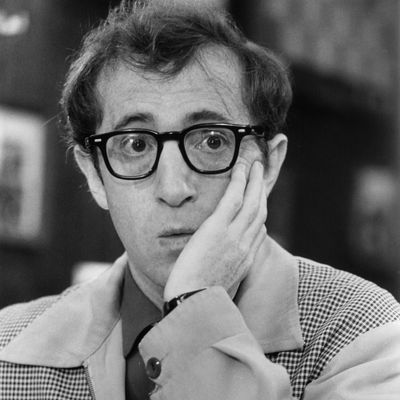

Woody Allen has never sent an email. He does not own a computer. (He admits to owning an iPhone, but only for making calls and listening to jazz while traveling.) After over 50 years in the film business, Allen’s daily routine hasn’t changed one iota: He still sketches out his script ideas in freehand on a yellow legal pad. And once the story starts to come together, he types it up on a 1957 edition Olympia SM-3 manual typewriter.

A recent study confirmed what Allen seems to know intuitively: In the modern workplace, neurotics can’t focus. Tracking the online activity of 40 information workers, an experiment conducted by researchers at UC Irvine, the MIT Media Lab, and Microsoft sought to understand how individual factors like personality and stress impacted a person’s ability to focus their attention.

The study honed in on two specific personality aspects, neuroticism and impulsivity. The academic definition of neuroticism, by the way, hews closely to the popular one, with some key distinctions. Neurotics do tend to be anxious, Woody Allen–like people; those who score high in this trait tend to be especially sensitive, and are likely to spend more time ruminating over their emotions than their non-neurotic counterparts. In the words of these researchers, neurotics are “prone to stress, report more daily problems, and tend to reanalyze prior events over and over in their minds.” The definition of impulsivity, as defined in this study, is simpler: It means, of course, that you lack self-restraint.

For two weeks, researchers tracked participants’ habits for all applications and online activity on their computers, logging both when they switched between applications (say, from email to Word), and when they switched activities within an application (such as opening up a new browser tab or switching between Word documents). It turned out that there was a strong correlation between neuroticism and a weakened ability to focus for sustained periods of time. The higher someone’s neuroticism, the lower their ability to focus for an extended period of time on a given task on their computer. This is because, or so the researchers theorized, focus comes with an opportunity cost: We all have limited attentional resources. And neurotics tend to spend a lot of time and attention focusing on the past — replaying conversations, worrying about that email they sent, wondering if they should have gotten the steak instead of the lobster.

It turns out that investing all of that mental energy in obsessing about everything but what is happening right in front of you can drain your attentional resources. With less energy and attention to spare, neurotics can have trouble filtering out all of the distractions that make it difficult to focus in the workplace. Perhaps less surprisingly, focus duration was also low for those people in the study who rated themselves as impulsive.

Past studies have also indicated that stress depletes our attentional resources. In keeping with this, the researchers found that how stressed out a person perceived themselves to be correlated strongly with a decreased ability to focus. This could be because being focused at work is itself associated with stress.

Of course, all the work we do at the office isn’t necessarily “focused.” Lots of the time we’re just on autopilot. In a separate study of 32 information workers, the same group of scientists (minus one) examined the rhythms of employees’ attention and online activity in the workplace. They looked at how frequently participants were in one of three states at work: focused, defined as highly engaged and highly challenged; rote, highly engaged but not challenged; and bored, not engaged or challenged. In a bit of good news, they found that participants reported being in the “focused” state most often. When people were focused, they most frequently reported being happy, but — in an unexpected twist — they also frequently reported being stressed.

Meanwhile, the participants also reported feeling happy while doing rote work, during which they very rarely reported feeling stressed. In other words, the participants experienced the greatest positive effect when doing rote work, rather than when doing focused work. The study authors theorized that this is because “when people are consumed by an activity, it can be either gratifying or stressful, depending on the context.”

Surprisingly, this finding questions the attainability of the much-touted “flow” state in the modern workplace. (Flow is a cornerstone concept of positive psychology, created by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; it’s being fully immersed, energized, challenged, and absorbed by the task you’re doing.) As the researchers noted, “prior work in flow suggests that being in a state of flow causes people to be happy; however, our results did not find this to be the case.”

Could it be that the sheer cacophony of technology burbling on our computer screens makes flow of any kind impossible? Or is it that we’re all just juggling so many tasks that even when we finally get into the zone, we still feel stressed? These remain open questions as the studies cited here are fairly small. More comprehensive research will be required before we can truly claim to understand the unpredictable attention span of the modern worker. But as an admitted neurotic myself, I can certainly understand why rote work is the happy place of the overanalytical mind. If neurotics tend to feel stressed out in general, and being focused is a task that could add to that stress — even if it’s rewarding — then rote work is definitely the safer bet. Perhaps this might even explain the massive trend in adult coloring books: staying in between the lines as a form of self-soothing.