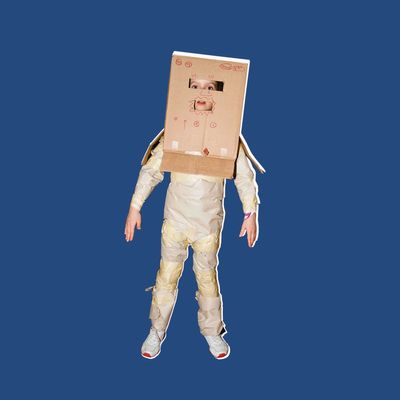

If you want to your computer to save the above image of a cute kid dressed up as a robot, it’s simple enough: just right-click and save-as, or the equivalent on your operating system. But if you, the human being, wanted to remember the image, the process is way less clear.

Yet the way we popularly conceptualize and measure memory — in the recalling of facts for exams, the remembering of your co-workers’ names so as not to feel like an ass at happy hour, the by-hearting of poetry to console yourself in times of crisis — acts as though it’s a hard drive sitting between your ears rather than a goopy mess of neurons.

Research on metaphors shows how much they frame our thinking. When crime is described to experimental subjects as a monster, they recommended force-based solutions like more jails or calling in the national guard; when it’s a disease, they recommend building more schools and public-health solutions.

There’s a long tradition of saying the mind is the latest technology: In Beyond the Brain, cognitive scientist Louise Barrett collects a few: Socrates said the mind was a wax tablet; John Locke said it was a blank slate where sense impressions are written; Sigmund Freud thought it a hydraulic system yearning for release. “The mind/brain has also been compared to an abbey, cathedral, aviary, theatre, and warehouse, as well as a filing cabinet, clockwork mechanism, camera obscura, and phonograph, and also a railway network and telephone exchange,” she writes. “The use of a computer metaphor is simply the most recent in a long line of tropes that pick up on the most advanced and complex technology of the day.”

Just as one should not mistake the map for the terrain, one should not mistake the metaphorical image for the real thing. “We understand how computer memory works, so we end up with the illusion that we understand how human memory works,” says Daphna Shohamy, a cognitive neuroscientist at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute. “For our computers, every unit of information is created equal — it has a size, but there’s no qualitative difference. In our brain memories, that’s not true at all.”

Human memories are stretchier, less reliable, and generally weirder than your computer may lead you to believe, as Shohamy and her peers in psychology and neuroscience have found. Here are a few of the ways:

There are different types of memories.

When you talk about your memories, it’s likely in the sense of a flashback — a sensory-based scene from earlier in your life, like in a movie. Scientists refer to this as “episodic memory,” since you’re remembering an episode from earlier in the TV series called You. But memory also takes the form of “reinforcement learning,” or figuring out how a system or interaction is supposed to work. It’s procedural, like sensing just how much to twist the key to get a fickle front door to lock or the right rhythm to swipe your subway card with. Fittingly enough, Shohamy’s lab has found that teen brains keep the two forms of memory more closely related than adults’. Not all memories are narratives that you can hold in your mind; some are just how you “remember how to do” a procedure.

Your memories change.

“You can disrupt the re-storage of the memory,” says New York University neuroscientist Elizabeth Phelps, who studies the intersection of emotion, learning and memory. In the language of mind science, memories are “plastic” — meaning that rather than being set in stone, they can be molded like clay.

In some ways, this is a destabilizing finding, and it explains why so many eyewitness-based convictions get overturned by DNA evidence. A landmark 1974 study had participants watch movie clips of fender benders, and found that if subjects were asked about how fast the car was going when they “smashed” into each other, people recall faster speeds than if they merely “hit.” They’ll even be more likely, as the New York Times reported, to recall shattered glass they never saw.

More hopefully, one of the goals of neuroscience is to find how this mutability can be used to help people with fear and anxiety disorders — since if you could alter the the memory of a trauma, it could free lots of people of lots of suffering. But from a research standpoint, it’s still early. “There is huge promise that we can understand them well enough to make clinical interventions, but we haven’t done it yet,” Phelps says.

Memories form depending on their relevance to your life.

Compare how you recall the hours spanning 6 p.m. to midnight on Tuesday, November 8, to the Tuesday before, November 1. If those memories were encoded like a computer stores them, there would be no difference — one six-hour recording of dinner and maybe a little Netflix, one six-hour recording of ballots coming in. But for anyone at all politically engaged, the events of Election Night — down to the New York Times’ aggravating electo-meter — will be seared into memory, down to the taste of the booze you reached to drown your sorrows in. “Maybe for a 1-year-old, the two Tuesdays may not differ so much. They don’t find personal significance,” Shohamy says. “Maybe someone who got engaged last Tuesday might have very strong memories for both events.” This is something that good teachers already know: If you want students to remember a lesson, you show them how it connects to their lives.

Your memories are tied together.

When you say that a new experience “reminds” you of something, that’s an indication of how your memories thread together. Shohamy says that her memories of Election Night aren’t just tied to other second Tuesdays of November, but “disastrous political events” that she’s lived through, like when she was a student in Israel and Yitzhak Rabin, a prime minister pushing the Middle East toward peace, was assassinated. New York felt like it did on the days after 9/11, or so I am told. “We connect the memories we have on a lot of different associative levels,” she says. “It’s not a folder saying, ‘Here are the Election Nights.’ But there are a lot of common features and feelings and concepts that we use to connect across memories.”

Relatedly, one of the best ways to learn a new fact is through “elaboration”: new thing X is like old thing Y. “The more you can explain about the way your new learning relates to prior knowledge,” write Peter Brown, Henry Roediger, and Mark McDaniel, authors of Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning, “the stronger your grasp of the new learning will be, and the more connections you create that will help you remember it later.” Like if you’re learning about heat transfer in physics, summon sensations to mind of how a hot cup of cocoa warms your hands on a cool winter evening.

The more surprising an experience is, the more likely you’ll recall it.

“We’re constantly generating expectations of what’s likely to happen,” Shohamy says, “and when what we expect doesn’t happen, that’s a big signal to our brain to pay attention.” Big surprises make for ready recall, whether that’s this month’s history-shaping election result; the mind-imploding, heart-expanding twist in Arrival; or a first date that goes way better than you hoped for. “Our brains are built to help us deal with the world in better ways and not just so we can reminisce,” she says. “Predicting the future is remembering what happened in the past. Our memories are a bridge between what happened and what will happen next.” Evolution has disposed us to readily record the unexpected, so that the next time something nuts happens, we’ll be prepared.