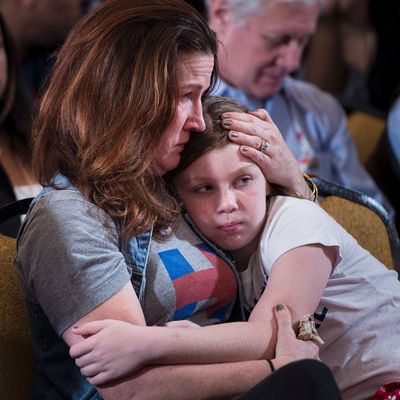

For Clinton supporters, it’s a very grown-up thing this country just did. Not grown-up like “mature” or “wise” or “responsible,” but grown-up in the way R-rated movies are grown-up — something you don’t really want your kid to watch, because there’s stuff in there that’s pretty uncomfortable to explain to a child.

Unlike an R-rated movie, though, this election isn’t something that can disappear with the click of a TV remote. There’s no way to entirely buffer kids from the anxiety and fear that many Americans are feeling right now — but nor should that be the goal. Science of Us talked to three psychologists about what this election might look like from a kid’s point of view.

They may not understand all the facts, but they are picking up on your feelings.

Even if you’ve kept the TV off, tucked all the newspapers away, and spent the past several months studiously avoiding election-talk at the dinner table, there’s no firewall foolproof enough to fully insulate your kid against the events of the day — and, specifically, how those events are making you feel. No matter how smooth you are, they’ll know from your face or voice or mannerisms that something’s wrong.

“Kids, even babies, are able to understand emotions in others. An infant obviously is not going to be able to look at their parent and understand that they’re reacting to something happening on the TV, but they do feel that their parent is upset,” says Erica Miller, a professor of psychology and education at Columbia Teachers College. “They’re able to identify anger, sadness,” especially in the people closest to them: “A lot of kids are so attuned to their own parents that they will have a sense that if a parent has tears in their eyes and is saying ‘everything’s fine’ that something’s amiss. And that can be confusing.”

Besides, kids talk. Whether you discuss the election with them or not, they’ll discuss it with one another. Onnie Rogers, a psychology professor at Northwestern University who studies identity and child development, told me a story about her sister, who has an 8-year-old daughter and a 10-year-old son; the kids and their mother discussed the election on Wednesday morning, Rogers says, but when they came home that afternoon, “they said at school they were talking about it with their friends, and people were really sad and upset.”

It’s a teachable moment for parents, she says: If kids are going to talk amongst themselves, then it’s up to the adults in their lives to give them the vocabulary and the know-how to do it in a way that’s healing rather than counterproductive. “At this peer level, kids are processing and trying to make sense of this. And I think that underscores the importance of parents and educators being engaged with kids around this topic and not sweeping it under the rug,” she says. “Because we assume that if we’re not talking about it with them, then they’re just not talking about it. But the reality is that they’re still processing, and we want to be able to give them the tools and resources to do it in a way that’s effective.”

They don’t want you to sugarcoat things.

Children are tougher than we think. “As adults, when we think of children, we sometimes think of them as very fragile or as not having developed any coping mechanisms yet,”says Larisa Heiphetz, an assistant psychology professor at Columbia University whose research focuses on social and moral cognition. But “kids actually do have some coping mechanisms, they do have some resilience, and we can play that up.”

One of those coping mechanisms may be a shorter-term view of the future: As we move closer to adulthood, we gain an increasing understanding of the idea that present actions can have long-term consequences. To a kindergartener, though, something that seems frightening now may be easily shaken off tomorrow.

Compared to adults, children also have a relatively sunny view of their fellow humans. While kids have a fairly developed sense of morality by age 7 or 8 — by that time, they tend to share adults’ belief that a person is defined in large part by their moral values — they’re more forgiving than adults in their belief that those values can change for the better. “There’s some work suggesting that children might be slightly more optimistic than adults about human nature,” she says. “For example, really young kids will say that someone who did lots and lots of bad things will still do good things in the future. Whereas adults will say that they’ll continue to do bad things.”

In other words: They can take it. All the psychologists I spoke to agreed that if you have a kid wondering why you’re upset, the best approach is to be honest, tailoring your response to their age. “There is a space for parents to very intentionally and strategically be honest with their kids — that you are sad about this outcome, that it is unsettling and unnerving, that it raises a lot of fears,” Rogers says. Open conversation also helps to validate their own concerns, she adds: “Kids have been in tune with some of the conversations that have been happening around this particular election. Particularly kids of color and from immigrant families, they are fearful. And it’s important that parents, teachers, educators acknowledge that as a real and sincere experience.”

But they do want some reassurance.

There’s age-appropriate openness, and then there’s no-holds-barred, over-the-top openness. “Honesty does not necessarily mean unfiltered or brutal,” Rogers says. “So saying, ‘Oh, it’s okay, Mom and Dad are happy, everything’s fine,’ is certainly not the answer,” but on the other hand, “the rage and screaming and yelling that one might want to do with a partner or a peer is also not appropriate in front of children.”

For young kids especially, it may be best to let them guide the conversation — if they ask a question, answer it, but don’t necessarily raise a litany of issues unprompted. “For a young child, it may not be appropriate to share every kind of fear that came up,” Miller says. “You don’t want your child to be scared all the time. You want them to have a secure attachment to the world. So if you are constantly being worried about what’s happening next to your family, which does make sense, it’s also your job as a parent to protect your child from the unknowns.”

This election can shape how they feel about voting over the long term.

“For some kids, this is really the first election where they’re old enough to understand what an election is,” says Heiphetz. “They might have seen their parents vote, their grandparents, other people in their family, but the outcome at the national level was very different from what their family wanted or talked about for a long time. For a child, that can be a little bit confusing or discouraging.”

Even if their first exposure to the electoral process was a negative one, though, there are ways to make sure they don’t feel turned off from their civic duty before they’re even old enough to fulfill it. One is to put the act of voting in context: “We might want to say, ‘Voting is very important, but here are some other things we might want to do because voting is not sufficient,’” Heiphetz says. “‘It’s one of the biggest ways we can effect the kind of change we want, but there are also many other steps we can take if we want something to change the world.”

But it’s also important, Rogers says, to emphasize the ways in which the world will stay the same — that governmental checks and balances, close communities, and cultural values all stand between threatening rhetoric and reality. A friend of hers, Rogers says, told her a story the other day about her daughter: “They’re a multiracial family, and her 7-year-old asked her if slavery could happen again … [She] said, ‘Well, because Donald Trump really hates black people, and if a lot of people voted for him, then that means a lot of people might hate black people.’” And “[the mother] said, ‘No, it wouldn’t happen again, there’s too many people that would fight against it.” Kids take things literally, including threats of dramatic change; one of the best ways to defuse that threat is to highlight the people and institutions that stand between what they know and what they don’t.

This may be especially important for teens, who are watching things unfold from a uniquely turbulent vantage point: To some, this election may represent a dramatic shift between the world they knew as children and the one they’re entering as adults. “High-school kids particularly, who grew up in an era where they got to see the first black president, they got to see the first female [major-party] candidate, they got to see DOMA repealed — they grew up in a world with all these things were happening that were so exciting in terms of equality,” Heiphetz says. “And now they’re wondering, ‘Is that going to be taken away?’ ‘What’s the adult world that I’m stepping into, how is that going to look?’” Right now, that’s anybody’s guess; even as minors, though, they have agency, and it’s up to adults to remind them of that fact. A sense of control is a powerful salve.