For the past three months, I’ve been covering a Manhattan murder trial that might finally solve the mystery of what happened to Etan Patz, the 6-year-old boy who vanished on his way to the school bus in 1979. In my time in the courtroom, several questions I’ve heard have stuck out. Like, “Do you have any major problem communicating with other planets?” And, “Do you sometimes have strange feelings in your body? Do these feeling only occur on Tuesdays?” And how about, “Have you ever felt that people were following you? Did you experience an increase in appetite during those times?”

These aren’t the type of questions that often come up during witness examination. You normally hear the where-were-you-on-the-night-of inquiries that establish means, motive, and opportunity. But this is a trial involving an allegedly mentally ill defendant, and these are questions that forensic psychologists testified they asked him to determine if he has a legitimate mental disorder — or if he’s just faking it.

You might think someone would have to be insane to say they get funny feelings every time Tuesday rolls around. And probably you’re unwell if you say you get a little hungry when you think people are spying on you. But in fact it’s just the opposite: Making these claims can show that you’re not, in fact, mentally ill. You’re only pretending.

Welcome to the strange science of malingering, a fancy word for faking illness in order to gain an advantage of some kind. It’s an area of psychological study that highlights the counterintuitive orderliness of insanity and also reveals that many people have no idea what it’s like to have a genuine mental disorder.

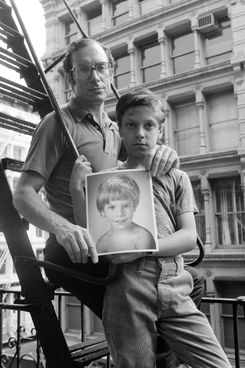

Malingering has emerged as an important issue in the Etan Patz murder trial, in which a 56-year-old man named Pedro Hernandez sits accused of killing the first-grader, who disappeared in 1979. It’s a famous case; Etan was one of the first missing children to appear on the side of a milk carton, and the day he vanished is now National Missing Children’s Day.

Hernandez was arrested in 2012 when he told police that he lured Etan into the basement of a corner store in Soho, then strangled the child and disposed of his body, which has never been found. Hernandez’s lawyers now argue that that confession was false. Defense witnesses have testified that Hernandez has an abnormally low IQ and a mental illness that prevents him from telling fact from fantasy. Prosecutors, meanwhile, have tried to cast doubt on Hernandez’s diagnosis, suggesting that he has been faking symptoms to avoid punishment for real crimes.

This kind of battle, waged at the nexus of law and psychology, is often a part of high-profile legal cases involving defendants who may be insane. James Holmes, the gunman in the 2012 Colorado movie-theater massacre, was tested before his trial to determine whether he was really schizophrenic. And several examinations found “Son of Sam” serial killer David Berkowitz competent to stand trial, even though he had claimed to be taking orders from a dog when he confessed to murdering his victims.

Of course, court-appointed psychologists also sometimes find legitimate mental disorders, like the current case of an Ithaca man who in December killed a UPS driver, apparently believing he was assassinating Donald Trump. The victim’s family cried malingering, but two psychologists determined that the defendant is genuinely ill and unfit to stand trial.

So how do psychologists tell whether someone has a real mental disorder, or whether they’re trying to pull a fast one?

The strange questions that I heard in court are part of a test called the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms, second edition. It’s one of the most widely used of a number of evaluation tools designed to detect fabrication or exaggeration of symptoms. Richard Rogers, the psychologist who created the SIRS test in 1992 and updated it in 2010, told me how forensic psychologists use tests and interview techniques to find the fakers.

A layperson might think that convincing someone you’re mentally ill is just a matter of acting irrational and claiming to have wacky symptoms. But mental illness isn’t simply random in its effects; its symptoms adhere to an order and taxonomy known to psychologists, which becomes useful for detecting phonies.

The SIRS-2 comprises about 45 minutes’ worth of questions designed to catch people who claim to be experiencing things of a variety or intensity that truly mentally ill people actually rarely experience. One detection strategy, for example, is to look for unlikely symptom combinations, said Rogers. “For someone who is faking a mental disorder, they don’t know what symptoms tend to go together and what symptoms tend not to go together.” That’s how you end up with a question pair like, “Have you ever felt that people were following you? Did you experience an increase in appetite during those times?” In reality, it’s quite unlikely that a paranoid person would feel an increase in appetite. So claiming to experience those symptoms together is an indication there may be some fakery afoot.

Other questions are designed to trip up would-be malingerers who have erroneous notions about mental illness. Saying yes to the question about communicating with other planets, for instance, is a red flag because that’s just not a delusion that people with mental illness generally have.

“People who are truly mentally ill don’t talk to other planets,” said Tali Walters, a forensic psychologist and expert witness. Delusions generally have some connection to someone’s actual life, she said. During the Cold War, for instance, delusional people often believed that communists were conspiring against them. Walters said she evaluated a genuinely disordered man arrested for shooting a police officer around 9/11 who became convinced he was part of the war in Afghanistan. “It all had some strings attached to reality, even though it was totally fabricated.”

In general, claiming to experience more and more strange symptoms is often a giveaway that a person is malingering. “If you just think more is better, more bizarre is better, if those are your presentation strategies, the chances are good that this is not going to succeed,” Rogers said.

Walters described a relevant situation that came up in her recent evaluation of a man in jail, facing trial. (She said she couldn’t disclose the details of the alleged crime.) When she asked him what kind of food he missed, he said, “Pepperoni and cat food.”

“Oh, do you like cat food?” she asked.

“Yes, I eat the dry kind,” he responded.

“It’s more likely that he’s faking it with me,” she said. “Because it’s so kind of bizarre, and not in a mentally ill kind of way.” Eating cat food is simply a strange behavior, one that doesn’t fits into a known pattern of mental illness symptoms, she said.

Walter said another thing about that interaction indicated possible malingering: When the man made his kibble claim he looked straight at her. Someone who’s legitimately mentally ill would likely know that a statement like that would be socially unacceptable, and would at least seem ashamed to say it, Walters said.

Put another way: A successful malingerer thus needs to have a fairly sophisticated understanding of mental illness and its effects. “You have to decide how much does your behavior change as a result of the reported symptoms, as well as how much insight you want to have into them,” said Rogers.

Because of the acting ability that’s required, one of a forensic psychologist’s most effective strategies is simply spending time with a subject, or putting them in an environment where they can be observed over a period of days or weeks.“I’ve never heard of anyone who can malinger 24 hours a day for 20 days, because it’s exhausting,” Walters said. If someone says he’s hearing voices ordering him to kill himself but can then be observed talking and laughing with others and eating and sleeping regularly, you may have found a malingerer, she said.

An evaluator will also look for corroboration of a mental disorder prior to the commission of a crime, by examining medical records or interviewing family members. A malingerer that starts acting odd as soon as they’re in handcuffs is not going to be very successful.

Rogers offered one caveat to all this: “We don’t know the ones we don’t catch.” Psychologists don’t learn anything from the malingerers who get away with faking insanity, because they never know they exist.

In a trial, the final and most important assessment of a defendant comes from jurors, who sometimes hear conflicting expert opinions from psychologists testifying on either side. That’s the case in the trial of Pedro Hernandez, which heads into verdict deliberations this week. As they begin to decide whether Hernandez is a murderer, they’ll need to first consider the question of whether he’s a malingerer.