It must be pretty cool being you, at least compared to all the poor schlubs you hang out with. After all, in a lot of ways, you’re better than most of the people you know — you’re probably healthier, more moral, even better at knowing when you’re being lied to. You’re a better driver; you’re going to live longer. Oh, and you’re better at cutting through all the bias to have a clear-eyed sense of who you really are.

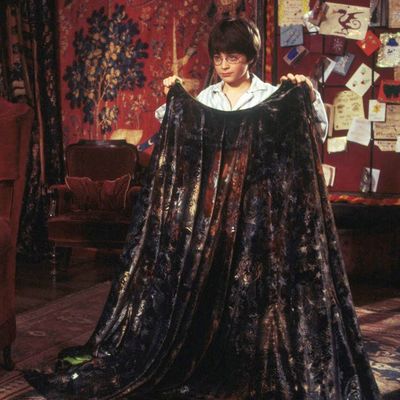

And hey, maybe one of those is true! Generally speaking, though, we all tend to walk around with an overinflated sense of our own greatness, a phenomenon called “illusory superiority”: Statistically speaking, it’s impossible for all of us to be above average, and yet we all believe it to be true, in a staggeringly wide variety of areas. And in a study recently published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology and highlighted by Juliet Hodges at BPS Research Digest, researchers added one more to the pile: We all have too much faith in our powers of observation and not enough in other people’s. It’s a bias that the authors nicknamed the “invisibility cloak effect” — we all believe we can linger in a room unnoticed and soak up the scene, everyone around us oblivious to our watchful gaze.

In the first part of the study, volunteers filled out an online survey about their observation skills. As expected, most participants claimed to be exceptional in two ways: more observant than the average person, and more likely to fly under the radar, too. When the researchers asked the same questions in a real-life context — this time, to college students who had just left the cafeteria — the results were the same: Once again, the participants said they paid more careful attention to the people they were with than the other way around. (“They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person,” Hodges noted, “not because they themselves were being watched.”)

In the second part of the study, the authors set up their own scenario to see the bias in action, putting two volunteers at a time in what they believed to be a waiting room before the real experiment started. In reality, it was the experiment: After several minutes together, the two people were each taken to another room and told to list either (a) everything they had observed about the other person (this person was designated the “observer”), or (b) everything about themselves that they thought the other person had noted (the “target”). Across the board, the observer’s list was longer and more detailed than the target’s — meaning, as the invisibility-cloak illusion dictated, that whoever was being watched underestimated just how much the watcher was taking in. Which might be a hard pill for the average person to swallow — but then again, you’re more humble than the average person.