Everyone has a person they’re waiting on a text from: an errant boyfriend, an impatient boss, an overdue Seamless order. I just spent a stretch of my life waiting on texts from several people — not friends or co-workers or food-delivery guys. No, lately I’ve been waiting on texts from a bunch of Jewish guys near Cleveland asking me to cut their hair.

This all started when I got a new phone in November. I had noticed that my personal and work lives were overlapping too often on my personal smartphone — a device I sometimes operated while incapacitated. I decided to join the shamefully privileged two-phones club: one for Snapchat, one for Outlook.

A few hours after my brand-new rose-gold iPhone was activated, I got my first text. “2 haircuts today…. ? Afternoon or evening. Like 8pm?” it read. The phone number had a Cleveland area code. As someone with about 1,200 unread emails in her inbox, I have a laissez-faire approach to inexplicable and unanswerable messages. It barely registered.

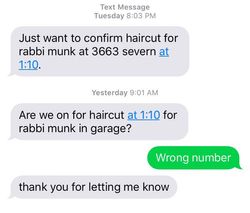

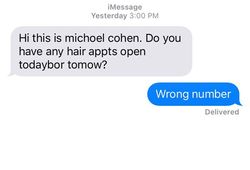

But the texts didn’t let up. “Just want to confirm haircut for rabbi munk at 3663 severn at 1:10.” “Hi this is michoel cohen. Do you have any hair appts open todaybor tomow?” “Are we on for haircut at 1:10 for rabbi munk in garage?” Poor Rabbi Munk! I began to gently tell my new contacts that they had the wrong number. But with the barrage of appointment requests I’d received, it felt more like I was the one who had the wrong number.

I was living — it soon became clear — with someone else’s phone number. We’ll call her Minda. By the second week of living with Minda’s old phone number, I was no longer bothered by the messages. They’d become new clues in the digital identity I’d inadvertently inherited. Minda’s life events were also my life events, and studying her incoming texts became a hobby. I started telling my friends about Minda, updating them on her life in the same way I might talk about a distant Facebook friend whose status updates are fascinatingly suburban. Based on what I knew, Minda lived in a tight-knit Orthodox Jewish community somewhere near Cleveland, Ohio. She cut hair for a living, while also taking care of a newborn. Her husband sometimes made sushi? Judging by the amount of texts and phone calls I received, she seemed popular. Or at least, she was connected to her community in a way that I envied.

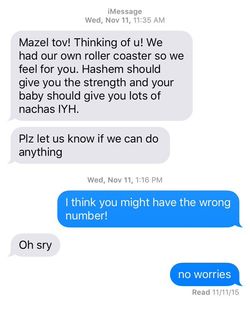

When I received a series of messages peppered with felicitations and Yiddish, I was able to discern that she’d recently had a baby — or, as her friends called it, a “little tzaddikle.” A few people said they were “davening” (praying) for her. I found myself worrying about Minda, and feeling grateful for the support from her community.

The texts only gave me snippets of Minda’s life, but it was clear it was vastly different from mine. As a 20-something journalist who spends her free time trading cat GIFs on Gchat and drinking wine in her bathtub, community-building for me means giving apartment-building neighbors nicknames like “crazy girl” and “sir cooks-a-lot.” While Minda’s friends were texting to congratulate her on her newborn, mine were sending me updates on their latest UTIs. She was able to support her family as a freelance stylist, while the majority of my disposable salary goes to canceled ClassPass appointments. If my boyfriend made me sushi, I’d probably be suspicious he cheated on me.

Because of this, even the most mundane mass texts — including one advertising “yoshon” (kosher grain) muffins or “chalav yisroel Reesies crunch cookies” (made, I learned, with dairy products obtained under the supervision of an observant Jew) — were precious to me. And it was impossible to resist showing off the view of my window into a stranger’s life: Eventually, I tweeted a few screenshots.

Not long after my tweet, I got a text message: “Hi, you have my wifes old phone number. Im sorry if anyone bother you about our hairdressing business. or our newborn, or anything else. if anyone is looking for us and its not too much of a bother you can forward them this number. Thanks you so much!” Until that moment, I realized, I’d imagined Minda and her family as residents of a Christopher Nolan-esque fourth dimension — a parallel universe it was impossible to contact. But, of course, despite what you might have heard, Cleveland belongs firmly to our dimension and universe.

This new communication thrilled and embarrassed me. I cannot remember a time where I typed and deleted sentences so frantically. I’d thought of myself as a kind of Orthodox Hairdresser NSA, silently intercepting texts intended for someone else — instead, I was the most obvious kind of gawker. Of course they’d find out and (rightfully) think I was a creep. I introduced myself to Minda’s husband and hesitantly expressed admiration for his family. He humored me, and even revealed that he ran a private sushi-delivery business from his house on Saturdays. He was worried about losing business, so I told him I’d forward any incoming texts.

Needless to say, I informed all of my friends in the Minda loop of the breakthrough. “You have to go to Ohio!” one person declared with certainty, offering to film the encounter. “It’s too early for that,” I replied, as if it were an actual possibility. I’d read so many tales of serendipitous internet encounters that part of me wanted to establish an everlasting friendship with these Orthodox Jews from Ohio. Maybe Minda was my Brother Orange.

I adopted my forwarding responsibilities with pride. And I had plenty of work to keep up with: requests to put some Minda haircuts into an upcoming kollel auction, neighbors wondering if they could borrow a car-seat adapter, an acquaintance looking for a ride, another trying to drop in on New Years, something about a “hashgacha job,” and even the lone word “here.” They stood in stark contrast to what was on my personal phone: a mix of one-sided conversations with robots — Twitter verification codes, Uber arrival alerts, Cleanly pickup warnings, invitations to track a Seamless order — and rambling, emoji- and abbreviation-filled conversations with friends. If her text-istence was evidence of her strong ties to her community, mine was evidence of my love of Seamless. My Venmo alerts were often the only evidence I went out and did something. And even then, that something was typically represented by a single wineglass emoji.

One day I forwarded an image from a mass text advertising “fillets for Chanuka” and Minda’s husband couldn’t open it. “Can u send that to my wife?” he asked, and gave me her number. Whoa, I thought. It’s all happening. I sent it her way and then introduced myself as the person who’d inherited her number. “Yea:), I have lots of stories with that number. I heard you do too,” she said. I took this to mean that she’d read my Tweet, which made me feel creepy again. I tried forwarding a message to her the next day, and she didn’t respond. “Minda just needs space,” I told my friends when they asked for updates.

A month later my personal phone was stolen. And because I was too broke to replace it, I decided to transfer my original number to my new device. That meant giving up Minda’s number. I’ve buried a fair share of iPhones in my day, but losing Minda’s number felt like losing a community.

I’ve spent a good amount of my life stalking friends on Facebook, celebrities on Instagram, and writers on Twitter. But getting a midwestern Orthodox family’s incoming texts was a kind of voyeurism I’d never experienced. I wasn’t watching Minda — in a wholly unintentional and largely unfixable way, I had become her. The more we rely on technology to communicate, the more we copy some portion of our actual identities onto our phones and computers. Because a phone company randomly assigned me her number, I was, for a month, a new mom, a hairstylist, the wife of a sushi-delivery guy to a small community of people in Ohio.

It was captivating, and more than a little disturbing. What would I think if someone else suddenly started inheriting my texts? Or, maybe worse, what would they think of me? Minda has supportive friends and strong community ties; her life is one to aspire to. But I’m not sure I’d like what a stranger would think if she became me for a month. Among other things, experience made a very strong case for enabling the longest possible lock-screen passcode on my own smartphone

And yet, I still hope that whoever gets to be Minda next appreciates it as much as I did. And that Rabbi Munk gets his hair cut.