There are many things to learn from the long slog to today’s election. The candidates, their parties, their supporters, and the media directly confronted some of our nation’s most pressing issues, including racism, xenophobia, misogyny, toxic nationalism, and capitalism. The lessons that can be derived this long period of national self-examination are multiple and deserve careful consideration. In the coming weeks, as pundits and commentators pick clean the bones of the campaign, we will hear about many of them.

Here is one modest addition: When it comes to computers, we’re screwed.

And when I say “we,” I mean everybody. Not just old people on dial-up, not just selfie-obsessed millennials, not just rich people, not just poor people, not just the candidates, and not just the media. Over the last decade — and particularly since the last presidential election — we’ve woven a vast networked technological apparatus, known to you and me as “computers and the internet,” into our national social, cultural, and political fabric. And we don’t know how it works or how to talk about it. The extent to which this election has been driven by technological incompetence and ignorance — by computer fuck-ups great and small — is unprecedented. And it’s very worrying.

Let’s start with — say it with me now — emails.

Clinton’s use of a private email server during her time as secretary of State has dogged her this entire campaign. It’s reasonable, if not obligatory, to criticize Clinton for using a private and potentially insecure email server; even if it’s not a prosecutable offense, it reflects poorly on her judgment and commitment to transparency.

Sadly, most of the specifics of the case seem to have been lost amidst hyperbolic and generally inaccurate reporting about the danger of the private server, as Philip Bump wrote in the Washington Post last year. We’ll set aside for now the byzantine technology protocols of the federal government that allegedly led to Clinton (and predecessor Colin Powell) using private email (essentially, official State Department email can’t be accessed on a mobile device) — though the fact that an essential technology was rendered too inconvenient to use by State Department IT tells us something about how bad we are at the cyber. Among other stories stemming from the scandal have been the claim that the server itself, which Clinton used to personally plan Benghazi, and Venmo Iran money (using the rocket emoji, natch), was “attacked” by hackers in China and Russia!

Well: “Attacked” is a strong word in this case. What many hackers do is scan IP addresses and ports — the network locations and entry points of servers — en masse, and then try to log in to servers using default names and passwords: “Admin,” “root,” and so on. Servers you use have been “attacked” in the same way! This is not to say that the server was secure — but precision about what the real danger was is important.

Similarly, the Trump refrain that Clinton “acid-washed” her server reflects basic ignorance about standard practice when you stop using a hard drive or other form of storage: You wipe it and write over the data so it can’t be recovered when the drives get hauled off to the dump or put out on the curb. It’s the digital equivalent of shredding a bank statement before putting it in the trash. Clinton’s server was wiped using an open-source program called BleachBit, which seems to have led the Trump campaign to refer to Clinton’s “acid-washing” the emails. It is not entirely clear if Trump actually believes that technicians literally dunked the server in acid or bleach.

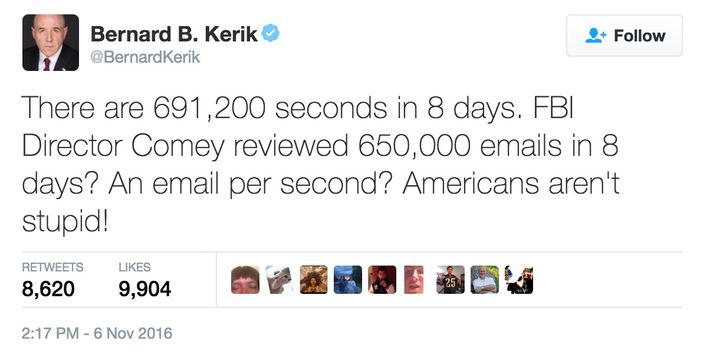

It somehow got even more comical this weekend when convicted criminal and former NYPD commissioner Bernard Kerik tried to perform some arithmetic in a now-deleted tweet.

Americans might not be stupid but Kerik sure is. Here is how the F.B.I. reviewed so many emails so quickly: They used a computer. Those computers, given the right search parameters, can review emails much quicker than, let’s say, six dudes in a conference room. General Michael Flynn, who is emphatically supporting Trump for president, has been baffled by the development, wondering what sort of quote-unquote “smart machines” the FBI used to run through the emails. You’ve heard of smartphones? These are like those, but bigger.

Breitbart, whose former executive chairman Steve Bannon is a high-ranking Trump official, has expressed similar skepticism toward these mysterious electric boxes that can read words. “One possible explanation for the speed of the investigation is that the FBI used smart machines that honed in on relevant emails,” the site wrote.

It’s like asking, “The average person can walk a mile in 20 minutes? How did this guy get across the country in five hours?” My dude, he took a plane.

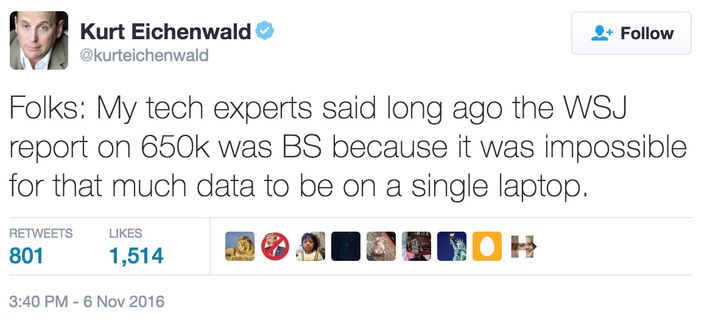

Reporter Kurt Eichenwald also made a numbers oopsie (and, like Kerik’s, the tweet has vanished).

The average size of an email, assuming it contains only text, is somewhere between 50 and 100 kilobytes. Let’s be generous and assume the upper bound here — 650,000 emails at 100 kb in size would be about 65 gigabytes. Any laptop made in the last 15 years can probably store that locally, and if one is using a remote server, you can assume the storage capacity to be higher. Even if a substantial amount of the emails contained images or file attachments, they shouldn’t overwhelm a laptop.

No one has come out of the email mess looking good, largely because no one seems to have any clue how computers are used or what they’re for. Clinton should have enough basic knowledge of computers and the law to recognize how out of line it would be to set up a private email server, no matter how much more convenient it is. The media should have a clear sense of exactly what Clinton did that was wrong, what the danger potentially was, and how the State Department was meaningfully affected by it. The Trump campaign and its surrogates should, at the very least, know what a computer is.

By the way, we haven’t even mentioned the WikiLeaks stuff! The most recent email dump, from Clinton campaign chair John Podesta, came about because the campaign’s IT desk told Podesta that an illegitimate phishing email requesting a password change was legitimate. To quote Sophocles, “Whoooooooooooops!!!!”

In some sense, it’s easy to forgive people — computers are still … relatively new, and certainly not many people are well-versed in the various technologies (uh, “laptops”) that the scandal has touched on. But when they are central to the function of, you know, democracy, it seems reasonable to ask that people know what they’re talking about.

This is an election where technical news could no longer be summed up in broad, casual strokes. Readers need precise language and knowledgable reporters to accurately portray the scope of events. Slate’s recent reveal of a Russian server pinging a Trump Organization marketing server — business as usual and hardly nefarious — is just the most recent example of mis- or underreported technology stories. Without specificity and expertise, nonevents get blown into scandals.

And unfortunately, there is no indication that we’re getting better, as Eichenwald and Bernie Kerik revealed this weekend. Both Clinton and Trump have said little about our growing cybersecurity concerns, other than that we really need to pay attention to “the cyber” because it’s so, so important. Continually, throughout this election cycle, intricate technical issues have had serious political implications, but the candidates, the press, and the citizenry all seem to content to treat computers and smartphones just as we have in the past: as magic black boxes that work on pixie dust. The gap between technical discussion and technical literacy during this campaign cycle was dangerously wide. If it gets any wider, who knows what will happen.