First things first. Horizon Zero Dawn, out for the PlayStation 4 on February 28, is a good video game. It’s one of the increasingly rare big-budget titles willing to take a chance on creating a new world, instead of trotting out yet another sequel. The game is set in a far-flung version of the future, where our own society has been destroyed and mankind lives on the margins, having reverted back to a more tribal, shamanistic type of existence. The wilds are full of menacing robotic dinosaurs, quick and dangerous and hard to kill. Ancient ruins are everywhere, but most humans stay away. It’s a world with hints of Mad Max or Riddley Walker, but it’s lusher than most postapocalyptic settings, and its characters speak plainly in a modern vernacular, even when referencing things like a “mad Sun-King” or a goddess known as the “All-Mother.” And despite the inherent goofiness of Dinobots roaming around, the game does an admirable job of making the machines truly frightening to take on, especially for the first time.

You play as Aloy, a young woman who has lived her entire life as an outcast of her matriarchal tribe. Raised without any idea as to why she was banished from the tribe or who her her mother was, Aloy spends the early part of the game winning back a place among the tribe, before being sent out to find answers in the wider world. Who was her mother? What happened to bring down civilization? Who or what created all these mechanical megafauna?

While these questions form the central narrative hook to pull you through the expansive main story line, make no mistake: The reasons to play Horizon Zero Dawn are these machines. Each has particular weaknesses and strengths, and learning how to account for them means using every bit of Aloy’s arsenal, which ranges from bows to trip wires to ropes you can use to tie down enemies, keeping them in place for a few moments. Movement for Aloy is key here — some of the best moments involve creeping through tall grass before bursting forward in a full sprint toward a massive beast, sliding underneath it while snapping off a bow shot at its vulnerable underbelly, and then popping back up into a diving roll and back into cover.

The core gameplay loop is simple but effective: take down machines, strip them for parts, use those parts to upgrade your weapons and armor, and then do it again. Especially during the early hours of the game, I was happy to blow off the main story line and instead just hunt down herds of mechanical creatures, earning experience to upgrade Aloy’s abilities and make her even deadlier to the machines wandering the world.

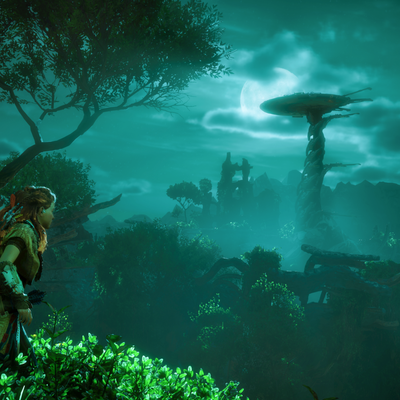

The game itself is beautiful. It was rare that I’d go for long without being struck by some vista or view point. The game’s full day-night cycle — combined with weather like snow, driving rain, fog, or sandstorms — creates memorable moments out of pure exploration, whether it’s looking down from a mesa at dusk and seeing the blue lights of the robot’s eyes slowly scanning the grasslands, or climbing up the side of a tall mountain at dawn, with the sun shooting rays of light through the early-morning haze all around you.

Why, then, did I find the game such a struggle to finish? It wasn’t the difficulty. While there are some hair-raising encounters in the game that will press you to use everything you’ve learned while fighting monstrosities, you have enough different ways to approach any major fight that a mixture of tactics will take down whatever is in front of you.

And the story’s real main hook — what happened to the world that came before this one, and why does Aloy seem to have such a deep connection to it? — is a good one. Even though any reader of sci-fi or fantasy may be able to predict the plot beats as they come, there’s enough thought and care put into crafting each reveal that I found myself always eager to learn a little bit more.

But there was a tension in all that. While I always wanted to advance the story line, I found myself not wanting to do the things that would let me learn more. Much of Horizon’s main-narrative quests can be broken down into a variation of “Go to this spot on the map, fight or sneak your way through these enemies, possibly fight a very large boss, and then explore this ruin.” It’s a template that quickly becomes rote, to the point where you can easily anticipate when the major battles will happen.

To the game designers’ credit, Aloy is a rarity in video games: a female protagonist presented without overt sexualization (looking at you, Tomb Raider). Strong, curious, and still carrying a bit of resentment from a lifetime of being treated as an outcast, she makes for an ideal adventurer — almost to a fault. By the time you’re about a third of the way through the game, Aloy has quickly gone from backwoods outcast to something of a celebrity within the tribal world of Horizon, with her being the main lever of action within the world at large. Got a problem? Aloy will handle it. While it allows for her to be in the center of things, it also creates a character whose rough edges are quickly polished off, turning her from aggrieved outsider into Mary Sue-ish superhero by the game’s end. She starts out interesting, only to become increasingly bland by the game’s end.

But I think the true root of the tedium I felt by the end of the game is due to the genre of the game itself: an open-world adventure title. Outside of first-person, multiplayer shooters, no other type of game has so thoroughly dominated the landscape of video games since the turn of the century, from Grand Theft Auto to Assasin’s Creed to Skyrim to Far Cry to the Witcher 3 — and it doesn’t help that Horizon liberally borrows from all of these games. There’s the mission design, which often finds you scanning for tracks and clues using a Bluetooth-ish earpiece called a Focus, much like in the Witcher 3 or the recent run of Batman open-world games. There’s the map mechanics, where you’ll climb large, brontosaurus-ish beasts called longnecks to unveil a large section of the game map, a similar mechanic used in Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed (and most other open-world titles from the publisher). There’s hunting down non-robotic wildlife to upgrade your ammo bags and clearing out bandit camps, as in Far Cry (the game that shares the most DNA with Horizon). But, most damning, Horizon also inherits the genre’s general tendency toward flab and bloat.

This can be felt in the main story line, which will take most players about 30 hours to complete. It’s a tale badly in need of an editor. It’s hard not to imagine how much tighter the story could have been if many of the extraneous characters and plotlines were excised, allowing the plot to center on the central mystery of the game. This would also have allowed for the sections that remained to get more polish in the writing and performance — when you’re creating and recording this much dialogue, tone-deaf moments start to pop up with more regularity.

For a certain type of audience, one who measures games using the rough equation of “X dollars divided by Y game hours equals the overall quality of game,” a 30-hour core story, plus a long list of side quests and challenges to complete, is all well and good. Your in-game map quickly becomes cramped with various things to do, and a dedicated player who wants to complete everything in the game will likely be able to sink 100 hours into it. But for me, a weariness had already set in by the time I watched the final credits roll, and when the Horizon game announced I was free to continue exploring stuff even after defeating the story’s main villain, I was ready to put the controller down.

But the same can be said for nearly any open-world action-adventure game I’ve played in the past 15 years. These open-world games are forced to serve two masters: creating a world where the player can roam freely, while also bolting on a pre-written story line for the player to move through. These two conceits are incredibly difficult to synthesize into something that feels satisfying. Hamstring players’ ability to do what they want too much in service of story, and the open world quickly feels more like a theme-park ride than a living, breathing place to explore. Create a world that’s overly dynamic and subject to change, and you introduce too many variables to allow for stories to achieve any sort of narrative drive. Apart from the Western-cowboy epic Red Dead Redemption, there hasn’t been an open-world game that has delivered what I’d call a complete and satisfying story, including sticking the landing (and even Red Dead Redemption suffered from monotonous stretches of gameplay).

In the world of PC and indie gaming, where budgets are smaller but creative experimentation is easier, this has largely led to games becoming all of one thing or the other. Pure sandbox games like Minecraft or Don’t Starve tend to have almost no narrative attached to them — they’re all about exploration and upgrading, usually with a survival element thrown in (i.e., you’ll need to feed and clothe and build a shelter for yourself). Games that want to tell a story, like Gone Home or Firewatch, are dead simple in gameplay mechanics, but rich in story detail and character work.

In the the world of big-budget games that also deliver on gameplay, relatively sophisticated storytelling is relegated to linear games, where players advance in a straight line from level to level, chapter to chapter. The studio Naughty Dog is turning out the best writing in games right now, with titles like The Last of Us and the Uncharted series showing a deftness in character and plot that leaves other developers in the dust — but the games play out the same way each time, with the only variation coming in, perhaps, how you handle certain combat sequences.

I’m not sure I’d want Horizon Zero Dawn to give up that ability to roam around for a more focused, linear experience. Stalking and killing the chromed-out machines roaming the wilds of Aloy’s world is often improvisational, surprising, and enjoyably, tough in a way that encourages you to continuously improve how you play. But the same can’t be said of the structure of the rest of the game, hemmed in by the dictates of how big-budget open-world games are currently designed.

It’s asking far too much of Horizon Zero Dawn to square this circle — this is the first open-world game from the developer, Guerrilla Games, and they’ve done an admirable job in just creating a game that easily is in the top tier of open-world games available right now. But, absent someone being able to truly reinvent how open-world adventure games are put together, even the best open world will be a place I’m increasingly reluctant to explore.