The company formerly known as Time Warner Cable — now known as Spectrum after a merger between Charter Communications and Time Warner Cable — is being sued by New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman for allegedly lying to customers, since at least 2012, about their internet services.

“The allegations in [this] lawsuit confirm what millions of New Yorkers have long suspected — Spectrum-Time Warner Cable has been ripping you off,” said Attorney General Schneiderman in a press release. Schneiderman was no doubt using the strongest language he could in a government statement. After reading the full complaint against Spectrum-Time Warner Cable, I’d say the state is accusing Time Warner Cable less of “ripping off” customers and more of “pissing on New Yorkers’ heads and telling them it’s raining.”

The full complaint is one of the rare legal briefs that makes for good, compelling reading, particularly for any Time Warner Cable customer who has stared at that “Netflix is having trouble loading” screen even though they’re paying for more than enough speed for Netflix, and they’ve already been on the phone with Time Warner Cable like four times about this, and Jesus Christ, just play some episodes of 30 Rock, please?

Partly, this is because of the deep insight it offers into potentially why — particularly from 2012 to 2014 — your Time Warner Cable internet sucked. But more importantly, thanks to numerous internal emails and documents from TWC, it gives a glimpse of the corporate culture inside TWC. It’s one where engineers and customer-support reps repeatedly and consistently bring up problems about the company’s internet-service plans, only to have their solutions shot down by execs higher up the ladder as being “too costly.” If the government’s case is accurate, it shows the combination of deceit and intentional neglect that created an ISP that sold customers one thing and provided something else altogether.

The complaint boils down to two essential charges: First, that starting in 2012, TWC began aggressively pushing customers to sign up for higher-priced internet-service subscriptions for ostensibly faster speeds — speeds the company knew it couldn’t deliver because its hardware was old and its infrastructure was decaying.

Second, that the company repeatedly promised reliable, “no buffering,” “no lag” internet, especially to services like Netflix or to online games like League of Legends, but was in fact purposefully letting the interconnections between TWC and outside companies degrade to an alarming degree — unless the companies, like Netflix, were willing to start paying for access to TWC customers.

Knowing It Was Too Slow

Per the state’s complaint, TWC did three things that meant it could never deliver the speeds it was promising to customers — particularly to those paying for 100-megabit-per-second (Mbps), 200-Mbps, and 300-Mbps speed tiers. The state claims TWC didn’t provide fast-enough modems for lease to deliver speeds promised, it didn’t provide wireless routers fast enough to deliver speeds promised (and made some outright laughable claims in its advertising about the abilities of its Wi-Fi), and it didn’t improve “last mile” infrastructure which delivers that coaxial cable into your home to sufficiently provide speeds promised.

First, let’s look at the modems TWC leased to customers. TWC mainly leased two types of modems — modems that used Data Over Cable Service Interface Specification (DOCSIS) 2.0, or “D2” modems, and more modern modems that used DOCSIS 3.0, or “D3” modems. The D2 modems only use one channel in a broadband connection, capping their download speed at 38Mbps, though as early as 2013 TWC knew that D2 modems were actually “non-compliant” for any speed above 20 Mbps. D3 modems can use multiple channels, allowing for much-faster internet speeds.

So, you would assume that anyone subscribing to a speed tier above 20 Mbps would get the faster D3 modem, right? According to the state, that didn’t happen. Customers subscribing to high-speed tiers were still being leased D2 modems. A snapshot in February of 2016 found that over 185,000 TWC customers on high-speed plans were being leased D2 modems that TWC knew could not deliver the speed the customers were paying for. Over all, TWC leased over 800,000 D2 modems to New Yorkers on high-speed plans for three months or more from 2012 until present.

And here begins the theme that repeats itself in the attorney general’s complaint: A good and decent course of action is recommended internally, and people higher up in the company decide not to do it. According to the complaint, TWC engineers in 2013 recommended switching out the slower D2 modems for D3 modems. But as one senior exec put it two years later in 2015, while the problem was still ongoing: “The solution is to get the D2s out, but we don’t have that kind of capital.” (In 2014, TWC posted an operating adjusted income of $4.8 billion.)

But, again, there was a chance to do the right thing. According to the complaint, there was an internal plan called “Ship to All” to simply upgrade every customer on a high-speed plan still using a D2 modem to a D3 modem. Problem solved, except that the plan was quickly killed due to fear of costs. Instead, the company went with what it called a “Raise Your Hand” approach, in which customers could get new modems, but only if they called TWC’s infamously bad customer service or waited in line at a TWC store, installed the new modem themselves or face an installation fee, and returned their old modem or get hit with a large “Unreturned Equipment Fee” charge. An internal email reveals this plan was explicitly designed to lower the number of people who would upgrade to the modem they needed in order to get the speeds required. And nowhere in the mailing and literature sent to customers did TWC explain that without this upgrade, customers would be stuck with far slower internet speeds than they were paying for.

This brings us to routers. According to the complaint, TWC also failed to provide wireless routers that could provide the speeds promised. TWC chose to continue to lease out (usually a single “gateway” device that combined a modem and Wi-Fi router) routers running an older protocol, 802.11n, which can theoretically deliver max speeds of 100 Mbps, but, like many Wi-Fi routers, delivers slower speeds in the real world. Per the complaint, an internal email from a senior TWC exec in charge of equipment put it bluntly: “We do not offer a [device] today that is capable of the peak Maxx speed of 300 Mbps via wireless … we are going to experience a mismatch between what we sell the customer and what they actually measure on their laptop/tablet/etc.” Again, it was recommended that TWC simply upgrade customers to the proper equipment, in this case sending out new Wi-Fi routers running the newer and much-faster protocol 802.11ac to anyone on a high-speed plan.

At times in the complaint, TWC’s claims can seem outright laughable. The attorney general’s office points toward a made claim that there would be no difference between wired and wireless internet with TWC’s internet package. First off, the company knew that many of its customers were on Wi-Fi routers that couldn’t deliver the speed it was promising. Second, interference alone can knock off nearly 25 percent of the speed on a Wi-Fi signal — and that’s before you start divvying up all that bandwidth between the multiple wireless devices many people have running in their homes. This image from an internal TWC presentation shows the elephant in the room when it comes to Wi-Fi.

Then there’s the issue of built infrastructure. If you avoided TWC’s outdated equipment and bought your own modem and router, rather than lease your modem and router from your ISP (and you really should just buy your own), it was highly unlikely you’d get the speeds you were paying for, especially at the higher speed tiers.

This is because TWC dragged its feet on building out its “last mile” infrastructure. Basically, when you are a cable internet subscriber, you share bandwidth with your “service group” (a.k.a., your neighbors). In February of 2016, the average service group in NYC had 340 subscribers sharing 608 Mbps of bandwidth. Per TWC’s engineers, the ideal is to have a network that only hits 50 percent capacity, even during peak hours (7 p.m. to 11 p.m.) — ensuring that anyone, even someone with a high-speed connection, can still utilize all the bandwidth they are paying for. Instead TWC regularly ran service groups at 80 percent capacity — meaning that someone paying a $110 a month for 300 Mbps service would likely only be able to achieve speeds in the range of 120 Mbps.

In a cycle that should now be familiar, it’s alleged that TWC knew this was a problem and decided on inaction as the best course. When a TWC exec says perhaps the 80 percent capacity limit needed to be lowered so the customers paying the most for their internet would reap more of the benefits, he was shot down. “That would drive 100’s of millions in investment,” replied a co-worker.

All of this led to a situation where people on 100 Mbps, 200 Mbps, or 300 Mbps plans (which the attorney general claims customer service reps were instructed to aggressively upsell customers on) were regularly averaging, at best, half the promised speed they had purchased from TWC.

Oh yeah, there’s also the claim that TWC actively deceived the FCC about its failure to provide its promised level of internet service. The complaint outlines a number of alleged shenanigans TWC pulled on the FCC from 2012 until present, including making false promises to upgrade all its customers to D3 modems and putting its thumb on speed tests — with the explicit approval of senior execs.

Putting Profit Over Reliability

All of the above, if true, paints a picture of a company that decided on inaction as much as possible to save money. But when the attorney general’s complaint turns to the unreliability, you see something more remarkable — the company allegedly ignoring upgrading its infrastructure in a deliberate attempt to extract money from the other side of the equation: content providers like Netflix and “backbone providers” like Level 3 or Akamai, which form the bulk of the modern internet. (TWC wasn’t alone in making these deals — all of the major ISPs at the time were forcing the same deals on various providers, in particular Netflix.)

Per the complaint, it worked like this: Starting in 2011, TWC was seeing tremendous growth in how much data users were demanding, especially as on-demand HD video streaming really began to take off. Between your ISP and the internet-at-large are ports (or, technically, internet exchange points, also known as peerings or interconnections). In 2011, TWC decided that instead of its previous policy of exchanging data between content and backbone providers and end users for free, it would begin charging. Some companies held out, including Netflix, the maker of the extremely popular online game League of Legends, and backbone provider Cogent.

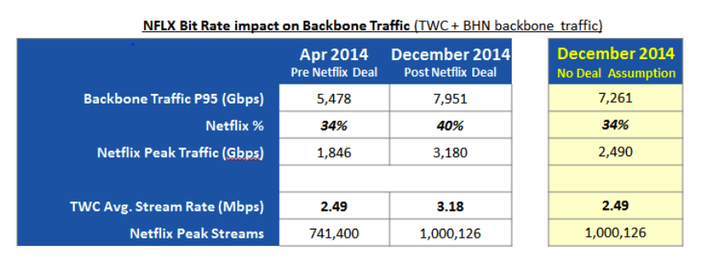

In the case of Netflix, the company refused to pay for access to TWC’s customers. In response, TWC didn’t cut them off entirely. Instead, it allegedly just neglected to upgrade the port capacity between TWC and Netflix, causing slower connections. Netflix offered to install, for free, its own OpenConnect hardware to ensure that it could deliver its content smoothly to TWC customers. TWC declined, instead continuing to insist that Netflix pay up. Netflix refused to pay from 2012 to 2014, when it finally caved. During this time, the complaint alleges that Netflix speeds were consistently below would be acceptable for HD streaming, about 3 Mbps. After Netflix struck a deal, it returned. The complaint republishes this chart, taken from a TWC internal presentation, about the “Netflix deal.”

In other words, had Netflix not played ball, TWC customers would have continued to see substandard speed from Netflix. The complaint alleges that TWC never informed customers that its ongoing dispute with Netflix was causing slower speeds — instead it ran ads about how TWC subscribers would “Enjoy Netflix better.”

The state claims much of the same is true in the case of Riot Games, creator of League of Legends, which initially refused to pay TWC until caving in August of 2015. Before the deal was struck, lag and data-packet loss (i.e., two of the things that can badly affect how well online game plays) for League of Legends players were far above the standards Riot liked to see. After it struck a deal, the numbers improved. Again, while it was in an ongoing dispute with one of the most popular online games in the world, TWC was also advertising that subscribers would experience games “with no lag time.”

Finally, there’s backbone provider Cogent (which carries much of Netflix’s data as well), which refused to ever pay for access to TWC’s customers. It consistently saw much-higher data-packet loss over TWC’s network. In an email republished in the complaint, Cogent at one point offered to split the costs of upgrading TWC’s network (a relatively low-cost $10,000), but TWC refused to do so. Cogent consistently remained the worst performing backbone provider on TWC right up until the FCC’s ruling in 2015 that ISPs were “common carriers,” meaning that ISPs were forced to act as neutral gateways to the internet — at which point Cogent saw its port capacity increase again.

Per the state, the reasoning behind all this was even explicitly laid out by a TWC exec in an email about port capacity, writing, “We really want content networks paying us for access and right now we force those through transit that do not want to pay.” (Forcing them “through transit” essentially means forcing content networks to find a more circuitous way to home users.)

The office of the attorney general received nearly 3,000 complaints from TWC customers about slow and unreliable internet service, and reproduces a few in the complaint, including this, which touches on TWC’s failure to keep up with port infrastructure: “We are being throttled on streaming services such as Youtube, Netflix, and Twitch while also having problems with Video games such as League of Legends.”

What Does It Mean for Spectrum-Time Warner Cable — And for You?

Well, for one, Charter seems pretty peeved that by acquiring Time Warner Cable, it’s now faced with both upgrading TWC’s infrastructure (a tremendously expensive proposition in NYC) and handling an aggressive and potentially very expensive lawsuit. “We are disappointed that the New York Attorney General chose to file this lawsuit regarding Time Warner Cable’s broadband speed advertisements that occurred prior to Charter’s merger,” said a spokesperson for Charter Communications when asked for comment. “Charter made significant commitments to New York State as part of our merger with Time Warner Cable in areas of network investment, broadband deployment and offerings, customer service, and jobs.”

After acquiring TWC for $55 billion, it’s not hard to imagine Charter may be feeling some buyer’s remorse at this point. The state is seeking, among other things, $5,000 for every instance of “false advertising” by TWC in New York state. This means, theoretically, that every advertisement Spectrum-TWC ran from January 1, 2012 until February 1, 2017 would cost Charter $5,000. Considering that nationally TWC spent about $245 million in 2014 on advertising, this could translate into a mind-boggling amount. Add additional damages — the attorney general also hopes to collect damages on behalf of the 900,000 customers directly affected — and you have a lawsuit that could end up costing Charter hundreds of millions of dollars.

This is also why it’s likely that Charter will settle this case out of court, as many cases like this often are. “This will settle because there seems to be a potential for a really high liability,” says University of Buffalo professor of law Mark Bartholomew. “And it’s pretty bad from a public relations standpoint. They’ll make a decision to stop the bleeding before going all the way to trial.” For Bartholomew, the case seems “pretty clear cut.”

If you’re on Spectrum-TWC, you can do several things right now. One, if you’re leasing your modem and router from them, stop. The Wirecutter-approved ARRIS SURFboard SB6183 and TP-Link Archer C7 will run you $175 together, which you’ll pay off in less than a year and a half of renting a modem and router from Spectrum, and you’ll be able to keep your modem if you switch providers.

Second, head here and test out your internet speeds — the New York attorney general’s office provides really easy-to-follow instructions. If possible, run these tests while plugged into your Ethernet — you want to test your actual internet speed, not how well your Wi-Fi router is working. If you’re not getting what you’re paying for, you can quickly file a complaint.

Third, you can always take your money elsewhere. Much of the lawsuit focuses on a time when TWC was really the only game in town. You may live where that’s still the case, but if not, consider going to another ISP. You’ll nearly always end up paying less thanks to introductory plans.

More broadly, though, we may be entering a different era. The FCC was actively working with TWC for years on trying to resolve these issues, with little to show for it. “One way to interpret this is that federal regulators have not faced up to Time Warner Cable the way the New York attorney general feels they need to do so, and so we turn to courts and false advertising law,” says Bartholomew. But this was also under Obama’s much-more active FCC, which passed regulation preventing TWC from charging data providers like Netflix extra to carry their data directly to consumers.

But Trump’s FCC is signalling that we’re about to enter a period of extreme deregulation, and Spectrum will likely soon be able to do as it pleases again at some point (though promises made by Charter made when acquiring Time Warner Cable will keep net neutrality in place for now). If that happens, consumers’ best hope of actually getting what they pay for will be either increased competition (unlikely, considering the high costs of entering the market) or lawsuits like this one. “We’ll have more and more state attorneys general taking the lead in customer protection,” says Bartholomew. “And not the feds.”