One day in 2014, the video-game designer Zoë Quinn decided to make herself a cyborg. And so, this being the modern world, she simply ordered a kit from the internet that would allow her, via a large sterilized syringe that she plunged into the webbing between her left thumb and index finger, to implant a microchip the size of a Tic Tac under her skin.

For a while, Quinn programmed the chip, which has a short-range radio transmitter that lets it send code to compatible devices, to do useful things, like call up a link to a game onto anyone’s phone that she touched, or make a new friend’s phone automatically text her contact information, which particularly came in handy at video-game conventions. But nowadays, she says, “I like the idea of using cool cyberpunk stuff to tell really stupid jokes.” The only script she currently runs on it pops up a notification window on the target phone that says, simply, “dicks.”

Quinn (who already had a magnet under the skin of her index finger, which she says allows her to “feel electromagnetic fields, like an additional sense,” as well as pick up anything magnetic as a party trick) originally installed the chip to promote a comedy video game she had begun building called It’s Not OK, Cupid. The game was inspired by her attempt to meet someone on the dating website, and, like many of Quinn’s projects, it was high concept: Set in a reality where people find love via an artificial intelligence, the game asks characters to scan a chip to verify that they are who they say they are. The joke, in part, is that authentication like that is unimaginable, really. “You’d have to be totally honest online,” she explains.

And as everyone knows, the internet isn’t built for accountability.

She never actually finished the game, however, and in the end, the chip wasn’t even vaguely the most dystopian OkCupid-related event in Quinn’s life. The previous December, while living in Boston, she went out with Eron Gjoni, a programmer she’d met on the site, with whom she had a 98 percent match. The first date involved drinks at a dive bar in Cambridge, sneaking into Harvard Stadium, a sleepover. They started a relationship that was intense at first, then off and on as the spring wound down. It was not an unusual course of events for a 20-something romance. But what followed was extraordinary, an act of revenge on an ex that became about much more than the two of them, that rippled across the video-game industry and far beyond. As Quinn writes in her memoir, Crash Override, out this September from Public Affairs, “My breakup required the intervention of the United Nations.”

The broad strokes of the episode — Gamergate, as it came to be called — go something like this: In August 2014, Gjoni published an extensive blog post accusing Quinn of various infidelities, including, he said, sleeping with a journalist at the gaming site Kotaku. The post was explosive, particularly on certain internet forums like 4chan, where it was suggested that she’d cheated on Gjoni in order to get a positive review of a game she’d built. In fact, no such review exists, but Quinn was an appealing target: She was already known for her work as a designer whose most famous game seemed built more to provoke an argument than to be enjoyable, and for her outspokenness on gender inequities in the industry.

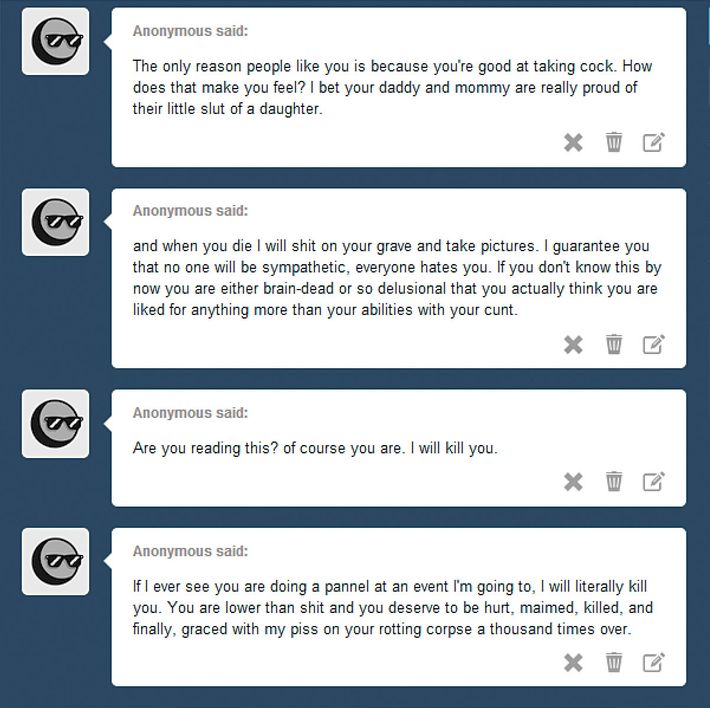

Almost instantly, Quinn began receiving messages like “If I ever see you are doing a pannel [sic] at an event I am going to, I will literally kill you. You are lower than shit and deserve to be hurt, maimed, killed, and finally, graced with my piss on your rotting corpse a thousand times over.” The slurs were constant, and deeply personal. But the participants — anonymous or pseudonymous commenters posting on 4chan, on ever-multiplying Reddit message boards like r/quinnspiracy, or even under their real names on Twitter — framed their attacks as just retribution for a moral lapse on Quinn’s part that was larger than what Quinn had “done” to her boyfriend. It was, in the phrase that became a joke almost as quickly as it became a rallying cry, “about ethics in gaming journalism.” Somehow, one woman’s fidelity in a relatively casual relationship was imagined to matter a huge amount, as if it were the epitome of everything wrong with not just gamer or internet culture but culture in general and even politics.

And then, horrifically, that all became true. Gamergate went on for months and months, taking on a life of its own. Milo Yiannopoulos, then a relatively anonymous blogger for Breitbart, made a specialty of targeting Quinn, raising his own profile and moving the fight into the right-wing pockets of internet culture, by publishing pieces like “Feminist Bullies Tearing the Video Game Industry Apart.” The argument shifted away from video games to how “social-justice warriors” like Quinn and her defenders (in other words, anyone who suggested the harassment was caused by sexism and prejudice) were intent on bending the culture to their politically correct will. Free speech — even masculinity in general — was under attack. A lawyer named Mike Cernovich became obsessed with the case and volunteered advice to Gjoni and his supporters when Quinn eventually sought a restraining order against her ex. “Young men have it rough,” he wrote on his blog about the wider cultural significance of Gamergate. By late 2015, Yiannopoulos and Cernovich had become internet-famous, with virtual armies of acolytes who shared a distinct sensibility. And they had found a new source of inspiration, something else at which to throw their frustrations, their nihilism, the identity-politics-obsessed rage that they’d honed during Gamergate: supporting the candidacy of our now-president.

All from the lashing out of one young man against one young woman.

Quinn, who is 29, cultivates a self-presentation that can make her seem a little bit like a video-game character, the heroine of her own mythological rendering. She swears a lot, rides a Harley, colors her hair silver-blonde with a blue streak that matches her silver-blue eye shadow, and dresses her anime curves dramatically: The first time we met, in New York, she was wearing tall black boots and a black-and-white striped dress under a double-breasted coat that dipped down in the back like a Renaissance Faire costume. She carried a studded Alexander McQueen backpack she was quick to tell me was a gift, not a purchase. “The first thing I ever heard about McQueen was he wanted the women he dresses to be somebody people are afraid of,” she explained. Everywhere else, too, she has worked to make herself seem tough, with gauges in her ears and tattoos on both arms, a lip ring and the just-visible marks of its disappeared eyebrow twin. She scowls in pictures, but in person there is an essential teenage softness to Quinn: She picks nervously at her glittery gold nail polish, confides easily.

As we began to talk, Quinn put down her phone, holstered in a case of her own design that’s decorated as a pink butt — the charging plug between the cheeks — and swallowed a pill. She has been diagnosed with complex PTSD, the result of prolonged, repeated exposure to trauma. Her eyes get red when she talks about “the troubles,” as she calls it, or when she talks about Gjoni, whom she refers to only as “the ex.” She is ambivalent about the degree to which identity politics has become the thing everyone associates with her. “My big thing was please stop sending me rape threats,” Quinn said of Gamergate. “It’s hard to call that feminist criticism.”

Quinn, like many adult gamers, was a child gamer first, finding some escape from the part of upstate New York where she grew up, which she calls “shit-kicker country.” Her father worked on motorcycles; bikers were their community. Quinn played on a 3DO, a failed early-’90s console that her father had picked up at a garage sale, and so her canon of formative games is full of “weird” ones no one else really played. Depression came on young; she tried to kill herself in early adolescence. In high school, she skewed goth, sang in a ska band, and lost her virginity to an older girl who then told the whole school. She didn’t have many friends her own age, but she did have dial-up internet. Online, she found thrills and comfort: tips on her favorite games; women talking about wanting other women; Rotten.com’s pictures of autopsies; Erowid’s suggestions for how to safely do drugs; and chat rooms filled with other depressed people who became her support system and stopped her from trying suicide again. “My circle of online friends helped steer me away from potentially stupid decisions with really scary consequences,” she writes in Crash Override.

She was a creature of message boards, in other words. Some of her online friends were the kind of grown men who were happy to let 15-year-old girls pretend to be 22. She traveled to meet a handful of them, doing exactly the thing every parent in that era was terrified their daughter might do. The farthest she went was bus-hopping to Alberta, Canada, to see a man she’d struck up a correspondence with on VampireFreaks (“like Facebook, for goths”). At 17, she broke up with a man who knocked out part of one of her molars in anger. “I fucking come from circumstances,” she says.

After high school, Quinn worked at a series of dead-end jobs and did some nude pinup modeling; her glasses and tattoos got her labeled in the fetish category. She tried stripping but found it didn’t mesh well with her shyness. She married, at 19, the roommate of a blue-haired tollbooth worker she’d become friends with during her many trips out of town to meet internet acquaintances. Quinn says it was “mostly for car insurance” that the couple made it legal.

Her husband didn’t do much for work: For a while, his primary source of income was as a “gold farmer” in the video game EverQuest, which meant that he’d sell the digital currency he racked up to other players looking for shortcuts. The couple wound up homeless, couch-surfing and occasionally sleeping in their car, until Quinn got a job as a rent-a-cop in Albany. Meanwhile, her online friendships deepened, especially the ones she made in an Internet Relay Chat room, a technology that attracts some of the most hard-core, deep-web users — the same kind of people who’d later become Gamergaters. “Years passed in that IRC room,” she writes. “I spent my 21st birthday chatting with my online friends because my husband had little interest in celebrating with me, and there was no other group of people I’d rather spend time with, even if they weren’t there with me in person.”

When the marriage ended, in 2010, Quinn moved to Toronto, where she had another friend from the internet. She decided to apply for one of six spots in a short seminar for women on making video games, put on by programmers concerned about the lack of women in the industry. At the informational session, Quinn raised her hand and asked whether the class discussion could extend to an online forum accessible to all the women who didn’t get in. She believes the question is why she won a spot in the course, which changed her career, and her life.

She began to make weird, often comic games that had almost no relationship to what we think of as video games. One is called Waiting for Godot: The Game (it never loads); another, called Jeff Goldblum Staring Contest, challenges players not to blink before his photo does. Money was tight, and she couldn’t land a full-time job at a studio, but she had made enough friends online that when her laptop broke, donors on a GoFundMe page paid for a new one.

Then, in a two-week binge, with the help of the writer Patrick Lindsey, Quinn finished a free, text-based game called Depression Quest, a choose-your-own-adventure-style journey in which the player struggles to make the minor decisions of daily life and, as the game progresses, finds that the healthy option — seeing friends, exercising rather than staying in bed, even seeking treatment — isn’t always available to her. It was the kind of idea-driven experimentation that excites indie designers and a certain kind of liberal-artsy video-game critic (“Writers liked it because it turns out a lot of writers have depression,” she told me), but which the majority of the video-game community doesn’t like at all. Depression Quest isn’t fun to play, and while that might be exactly the point Quinn was trying to make, for many, gaming is meant to be an escape from the difficulties of the real world, not a meditation on it.

When Quinn and Lindsey released Depression Quest in February 2014, it was a minor hit. It also occasioned a rape threat directed at Quinn, and a discussion on Wizardchan, a message board for adult male virgins, of how much the game “sucked” and how a woman could never really know true depression. Some of those users found Quinn’s phone number — she had entered it on a spreadsheet for volunteers after the Boston bombing — and began to call her.

Quinn doesn’t believe it was an accident that the brunt of the criticism was directed at her and not at her male co-writer. She saw friends on Twitter arguing that the gaming community didn’t have a problem with women, that “these are all lone wolves,” she said. “Motherfucker, then there’s a pack somewhere.” She posted the screenshots of the harassment she’d gotten. This mostly served as an invitation to escalate the attacks.

But it also helped her to cultivate a reputation as someone who spoke out on issues of inclusion and misogyny in the industry. She was chosen as one of two women on Game_Jam, a reality-TV show Maker Studios was trying to mount about indie game designers. Quinn helped incite a rebellion on the first day of filming when, among other things, the producer asked a male competitor if he thought his team was at a disadvantage because there was a “pretty woman” on it. Production shut down, costing Maker Studios hundreds of thousands of dollars. Quinn also flew out to San Francisco, with her then-boyfriend Gjoni, to give a talk at a gaming conference about the harassment she’d experienced.

Video games weren’t always such a male-dominated world. In the early days, they were so simple that there weren’t really ways to gender the games themselves (think Space Invaders). A successful 1970s game called King’s Quest was both designed by a woman and mostly played by a core audience of women in their 30s; female protagonists weren’t remarkable.

But in 1983, the industry experienced a severe recession — precipitated by a glut of low-quality games, and especially by the massive flop that was the Atari E.T. game, designed quickly at Steven Spielberg’s behest. (Fewer than a third of the 5 million copies produced were sold, resulting in a disaster so complete the company buried and cemented-over copies in a landfill in the New Mexico desert.)

The industry languished until Nintendo broke through in 1985, in part by marketing its consoles as toys, not just games — and thus launching itself into the gender-binary world of toy stores. (Its most famous product was Game Boy.) Research showed that more boys than girls were playing, which only reinforced the marketing strategies, which in turn reshaped the industry. To hook the adolescent-and-beyond segment, sex was introduced, at least in a theoretical way. Women were depicted on game covers as panting onlookers. Female protagonists, like Lara Croft, had builds that would give Barbie a crisis of confidence. Games like Myst and the Sims still had largely female playerships, but shooter games began to dominate the public conception of what a video game was.

And “gamer” matured into an identity — a distinctly modern, if not forward-looking, version of escapist masculinity. “Live in Your World. Play in Ours,” went the Sony PlayStation slogan. To observers, it could be hard to understand why a community of demographically advantaged young people would feel the need to protect their community from interlopers like Quinn, or the few female gamers before her who talked about gender in gaming. But any accommodations to diversity, or signals among journalists or developers that perhaps this might be valuable, did seem to provoke a hostile backlash. On 4chan and other sites, young men “policed the purity of games — the boundaries of what was a real game and what was not,” says Anita Sarkeesian, who, in 2012, came under attack from a proto-Gamergate horde for her video series called Tropes vs. Women in Video Games. She explains the intensity of harassment directed to women gamers with some sympathy. “When you have been told as a boy that games are for you, you have this deep sense of entitlement,” she told me. “Then they’re told they deserve fancy cars and hot women. When they don’t have that, they’re like, At least we have games. And then they see women saying, no, we’re here too.”

In June 2014, Gjoni and Quinn saw each other for a coda to their relationship, back in San Francisco once more. Even though they were in the same place, he communicated with her mostly via Facebook Messenger, from a library, trying to get her to confess to cheating, and asked for access to her accounts for proof. Gjoni had begun to compile a dossier of all their communications and of hers with others on public platforms.

According to Quinn’s account, they had sex one last time in San Francisco, and she says Gjoni became “violent” during the encounter. (Gjoni strongly denies this characterization.) She left with bruises on her arm, she says, and later found out she was pregnant. They went back and forth, in a series of emotional texts, about whether to keep the baby. She considered it, then thought about what she would be giving up. She had an abortion, stopped talking to Gjoni, blocked him on several forms of communication, and didn’t speak to him until the “Zoe Post,” as he titled it, went live. He wrote it, he told me, “as a cautionary tale for those who stood to be harmed by Zoë.”

Quinn has never directly addressed whether there was any validity to Gjoni’s claims that she’d cheated on him — texts between them show it was a complicated, intense relationship — and I never felt I needed to interrogate that. I think she got it about right in a Tumblr post from August 2014 when she wrote, “The idea that I am required to debunk a manifesto of my sexual past written by an openly malicious ex-boyfriend in order to continue participating in this industry is horrifying, and I won’t do it.” But recently, when I asked a friend to walk me through Gamergate attacks — which he had followed closely, with disgust — he said a couple of times that Quinn was “a really bad girlfriend.” I don’t think he meant it as a justification for all that the mob had unspooled, but it was as if something from deep inside his psyche had seeped out without him even realizing it was in there. “If I can target people who are in the mood to read stories about exes and horrible breakups,” Gjoni told Boston Magazine of his thinking, “I will have an audience.” He said he had estimated the chances that she would be harassed at 80 percent.

Quinn was at a bar with friends and her new boyfriend of a week, Alex Lifschitz, celebrating her 27th birthday, when she got a text from a friend: “You just got helldumped something fierce,” it said. “I tried to focus on the conversation at the table, but the agitated rattling of my phone was the only thing I could hear,” she writes in her book. “It was like counting the seconds between thunderclaps to see how far away the storm is and knowing it’s getting closer.”

As they stood outside the bar, one friend showed Quinn that her Wikipedia page had been changed to say she was going to die “soon”; it was then edited to show her date of death as her next public appearance. Nudes from her time modeling circulated. She and Lifschitz stayed up all night fielding messages and texting with friends who were working to get the posts deleted, taking screenshots of everything. (Quinn keeps the documentation of her harassment in a file called “Just Another Day at the Office.”)

Quinn can be analytical when talking about what happened to her: She believes that abusing her turned into a game in which participants tried to outdo one another with their vitriol; upvotes and retweets on social media showed them they’d scored. She also believes that Gjoni knew exactly the kind of situation he would create when he posted in the gamer forums. “Look at Elliot Rodger,” she told me, referring to the man who, in 2014, went on a killing spree at UC Santa Barbara. “He posted in the same places. Look at Dylann Roof. It’s like you’re playing Schrödinger’s murderer with all these people. Are they a shitty fucking edgelord” — a 4chan term of art for a certain kind of nihilist omnipresent on the site — “or are they actually going to kill me?” She also believes that he was taking advantage of his knowledge of her mental-health history. “Imagine all of the shitty tapes that play in the mind of a depressed person, externalized and with Twitter accounts blasting at you constantly.”

Quinn had displayed and lived so much of her life online that, with diligent searching, it was possible to burrow deeply into her psyche and personal history and friendships. Once her personal information had been exposed — her address and phone number were published, her Tumblr and other accounts were hacked into — she and Lifschitz began staying with friends. When her father’s address was posted, he began getting photographs in the mail of his daughter covered in a stranger’s actual semen. When Quinn’s grandfather died, she watched as posters in the forums boasted about combing his obituary for additional family members they could harass. Rather than try to reset her accounts, she deleted many of them. It was, she writes, “wrenching,” like burning photographs that don’t have negatives. Anyone who defended Quinn or the idea of a more diverse industry — Sarkeesian, developers like Brianna Wu and Phil Fish — also became targets.

When Quinn first reported the harassment to the police, they were confused, and wouldn’t accept the USB drive she presented as evidence, so she printed the worst of the worst, 70 pages of it until the ink ran out. Gjoni remained unapologetic. He told a journalist that he had written a sequel to the original post (which hadn’t mentioned the abortion) and it was set to auto-publish if he didn’t manually disable it within 24 hours after a court date — for instance, if he were jailed for violating the restraining order the police eventually granted Quinn.

Quinn stopped seeking criminal-harassment charges in the fall of 2016. Although a judge forbade Gjoni from posting any more about her, the mob of anonymous 4channers was nearly impossible for the judicial system to address — there were too many actors for liability to be clear, and the restraining order had only riled them up more.

When people would call Quinn’s phone, she said, they wouldn’t know what to do upon hearing her voice. “I’m a stand-in for other bullshit they’ve got going on,” she said. “They are the hero of their own story, and when you think you’re the good guy, you can get away with doing anything. If you think your enemy is a symbol and not a person, suddenly there’s a bunch of inhuman shit you have the emotional bandwidth to do, and I know, because I’ve been an asshole. If Gamergate had happened to somebody else, years earlier, I probably would’ve been on the wrong side. As a shitty teenager with mental illness that had a misogynist streak and loved video games? Yeah.”

On a sunny L.A. morning in April, just past the churning muscles of the USC swimmers hard at practice, a quiet stream of young people with tattoos or My Little Pony–colored hair — dusty rose, soft tangerine, one especially dreamy mane of bright turquoise and ’80s hot pink — walked into a classroom building, for the annual Queerness and Games conference. Attendees, a fair number of whom were women, people of color, or trans, were asked to write their preferred pronouns on a name tag; many scribbled down the gender-neutral “they.” Quinn wrote, “Any work for me :).”

This was as far as you could get from conferences like E3, where triple-A studios (the Hollywood-studio equivalent) showcase their wares. Here, there were panels on “Unruly Bodies: The Queer Physics of Fumblecore” and “Cute Games: Using Icelandic Krútt Music to Understand Revolution and Resistance in Alt/Queer Games.” Booths displayed games designed by attendees, many meant as social learning as much as play, like one on “emotional labor and otherness.”

Stephen Totilo, the editor of Kotaku, told me that one of the reasons Gamergate exploded when it did is that it coincided with the rise of indie game culture, in which newly powerful laptops and cheaper technology meant that outside studios, more people could make games about whatever seemed interesting to them, with any kind of protagonist they wanted. But gaming is a culture obsessed with delineation and hierarchies; Totilo points to the ’90s, when politicians began to blame video games for violence, as the moment when, in a defensive crouch, there arose the “sensibility that there is real gaming and there is the people outside who don’t get it.” And that any criticism of gaming culture, even from inside of it, amounted to an attack. As I listened to the conference’s keynote speaker, John Epler, answer questions from the audience about why he designed the hit game Dragon Age without “romanceable” queer or fat or dwarf characters, I began to think about how all anyone wanted in that room was to be able to imagine themselves in these imaginary worlds. A refuge from the more difficult one was what both sides of this intra-gaming war wanted, and yet it was so hard for each to see that in the other.

Quinn was late — her Harley had broken down — but when she arrived, big black sunglasses on, she was quickly surrounded by a circle of friends, whom she hugged, and conference attendees who shyly edged up to the circle to introduce themselves. She had told me in New York that what she missed most was her “freedom.” “There’s me, and then there’s the idea of me that other people have,” she said. “And if they think I’m some kind of internet hero or if they think I’m some kind of internet Satan, it’s still not me.”

She was at the conference to give a seven-minute “microtalk” on the subject of “what then, once you survive a time of acute distress.” She spoke a little nervously and ran through the coping mechanisms she had used during the intense onslaught of Gamergate. Hypervigilance, avoidance, the desire for intense security, constant self-scrutiny. “It sounds really sad when you tell someone who hasn’t had to deal with that kind of thing,” she said. I had observed that Quinn seemed to struggle with each of these in the time we spent together. Her phone constantly buzzes, and she told me she sleeps with it next to her, just in case something happens. She vacillates between the openness that is her natural mode — tweeting selfies in a new dress, pictures of her cat — and an intense fear that her words will be used against her. She has changed her cell-phone number three times since March.

During the worst of Gamergate, in the summer and fall of 2014, Quinn and Lifschitz had become obsessive, tracking message boards all day long, losing touch with the rest of the world. Quinn became “definitely an alcoholic,” she says. By the time the couple broke up, they were more “war buddies,” in her phrasing, than romantic partners. They hadn’t kissed in nine months, but also hadn’t left one another’s side for more than several hours at a time. “For months, it was every day waking up to some new nightmare that validates your worst ideas about the people and industry around you,” Lifschitz told me.

Gamergate’s harassment of Quinn slowed as 2015 began. It didn’t end — “A lot of what was happening in Gamergate was happening before it and has been happening since,” says Totilo. “The wounds are still more open than people realize” — but there were new targets: the actor Leslie Jones, supposedly ruining Ghostbusters by her mere presence in its reboot; John Boyega, doing the same with Star Wars; the new, more diverse Spider-Man comics — the list of villains went on and on. Gamergaters had not only created a whole new set of celebrities, like Yiannopoulos and Cernovich; it had solidified their methods (message-board-coordinated harassment on public-facing platforms, publishing personal information, creating memes about the target that made the whole thing seem fun) and their grudges had calcified into a worldview, one in which a cabal of identity-politics-obsessed feminists were nagging, whining, and guilting the world into watering down and ruining everything good that might have been.

The movement also had a new hero: Donald Trump, who didn’t have much to say about video games but had plenty to dog-whistle about identity politics. Steve Bannon, the former Breitbart chairman who served as the connection between the alt-right and the White House, has said that he was struck by the power of “rootless white males” on websites about World of Warcraft (which he’d learned about by investing in a firm that sought to profit off the kind of “gold farming” that Quinn’s ex-husband had done) and actively thought about how to co-opt their potential. Gradually, many of the accounts that had been obsessed with Quinn and ethics in video-game journalism changed their avatars to Pepe the Frog, tweeted about #MAGA, and explored white nationalism.

Quinn didn’t move on as quickly. She kept lurking in the chat rooms where her abuse had originated. She and Lifschitz had spent the past year becoming experts in documenting and reporting online harassment, and they decided to start an organization, Crash Override, that took on those tasks for others targeted by similar mobs. (The nonprofit is funded through Anita Sarkeesian’s Feminist Frequency.) Quinn became a figurehead for the movement; she and Sarkeesian were invited to speak before the U.N. about how to combat a “rising tide of online violence against women and girls.”

It is clear from Quinn’s book — already optioned by Amy Pascal, with Scarlett Johansson attached — that she has, in part, learned to make sense of her own situation by thinking about the systems that created it: Crash Override is almost more sociology than memoir. Quinn relates her own story, but mostly she’s interested in using it as a case study to explain why harassment happens and how difficult it is to get the big web-platform hosting services (Twitter, in particular) to respond helpfully. She’s smart and clear-eyed about how the attention economy of the internet and structural problems — hyperpartisanship, “content-neutral algorithms” — work against the targets of abuse.

But Quinn is also still feeling out what kind of person she’s become. Sometimes she seems invigorated by what she can do with her newly public platform — she refers to it as a “calling” in her book. Other times she sounds exhausted by indie gamers fixated on what she calls “misery porn” and unable, when they talk to her, to see past her as someone who has endured persecution. She remains very interested in identity, which in video games can be both thrillingly fluid and depressingly fixed. Her own is still in flux — she identifies as queer and is “pronoun-agnostic.” “Any kind of gender expression is performance for me, regardless of where it is on the spectrum,” she told me.

Quinn is nearly done building a new game, crowdfunded with $85,000 of Kickstarter contributions, to be released this fall. It’s a satirical full-motion video project about the campy erotic-fiction icon Chuck Tingle (known for titles like Buttageddon). A team of around ten built the game, but according to John Warren, her business partner on the project, Quinn is responsible for the majority of the programming, in addition to writing the narrative. “A lot of people are quick to assume she isn’t the one doing the technical stuff,” he says, in the same way “women at E3 always get asked if they’re in marketing.” It’s by far the most complex project she’s made.

Warren met Quinn when he tried to hire her to work on a game; he knew who she was from Gamergate but had also played Depression Quest. He liked her ear for dialogue and facility with branching narratives. The rest of his team ultimately vetoed Quinn’s hiring — “She was an attention magnet in a way they weren’t comfortable with,” Warren says — but Quinn and Warren kept talking and, eventually, she told him about Fail State, a game she’d been dreaming of making for a while.

The premise of Fail State, a meta one, is that players find themselves inside an imaginary, multiplayer, web-enabled game that was so disastrously built and incoherent that its creators will shut it down soon — a dying world that, it turns out, players love anyway. It’s a “microapocalypse,” in Warren’s words, in which “everyone is facing the end of this thing that’s really important to them.”

I thought about why Quinn might have been drawn to build a world like that, fallen and imploding and yet treasured, full of surprising joy and possibilities. During one of the hearings for the legal action against Gjoni, a judge who saw no grounds for criminal harassment charges suggested that Quinn get a job that didn’t involve the internet, if the internet had been so bad to her. She told him that there was no offline version of what she did. “You’re a smart kid,” he replied. “Find a different career.”

To Quinn, this was one of the most coldhearted moments of the whole ordeal. Because for all that the web has taken from her, she still believes it has given her far more. In her book, she writes, “The Internet was my home,” as it is all of ours now.

*This article appears in the July 24, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

Listen to this story and more features from New York and other magazines: Download the Audm app for your iPhone.