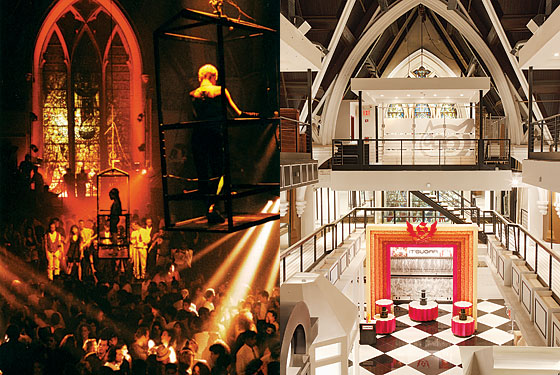

If the name Limelight conjures up images of face-painted ravers, go-go girls writhing in cages, gothic archways lit up in hellfire red, and club urchins like Richie Rich gliding around in diapers and roller skates (true story), prepare for some cognitive whiplash. On May 7, the former church turned den of debauchery in the eighties and nineties will be reincarnated once again, this time as an indoor mini-mall called Limelight Marketplace.

The 20th Street landmark’s lancet windows, labyrinthine layout, and soaring chapel are the same as they ever were, but the sex-and-drugs-fueled bacchanal is long gone. Where makeout booths and cocaine corners once stood, now you’ll find limited-edition sneakers, handmade belts, MarieBelle chocolates, Hunter boots, tubes of Sue Devitt lip gloss, scented soaps from Caswell-Massey, and Grimaldi’s pizza.

It is, by any estimation, a dizzying makeover of an iconic New York space. The building’s transformation from decrepit, boarded-up shell into the city’s newest shopping-and-gastronomy sensation is the brainchild of Jack Menashe, a third-generation retail developer who grew up working in his father’s Flushing store, a down-market clothing chain called Bang Bang—which quite possibly supplied a good number of eighties club-hoppers with their Lycra. In 2003, he opened a Soho boutique called Lounge on Broadway, which sold clothes while D.J.’s spun records and drinks were served at the store’s Casablanca Tea Room. Last winter, after Lounge succumbed to the recession, Menashe rented the main hall of Limelight—not a hard thing to do, as it had sat empty for two years after another club, Avalon, shuttered—to unload his extra stock. A small handwritten sign reading sample sale on the church’s Sixth Avenue entrance captured the attention of a mind-boggling number of shoppers. “The building,” Menashe says, “is a magnet.”

The space was too large and run-down for a single blue-chip retailer (a Gap, say, or an H&M) to anchor it. And its neighborhood, the gray area between Chelsea and Flatiron that’s still defined by the hulking ghost of a Barnes & Noble, has not been particularly hospitable to anything other than Starbucks and big-box stores.

So Menashe devised a novel retail strategy for post-recession New York. His plan was to fill the space with an eclectic mix of indie vendors, in the spirit of the hugely successful Chelsea Market. Menashe and a silent partner spent $15 million to build out 60-plus prefabricated “stalls” with individually designed façades. Before any contracts were signed (the Brazilian waxing salon J. Sisters was the first to ink a deal), architect James Mansour outfitted the three-level, multi-wing space with slots intended for specific types of retailers (a perfumery, a denim line, a home-furnishings brand). Then, says Menashe, “We found the pegs to fit the holes.” He rejected “tons” of businesses that didn’t fit his vision. “We thought about stationery,” he says, “then moved away from that. There’s no sex appeal.” Retailers could sign one-year leases for a fraction of the cost of a stand-alone storefront. The ground-level stalls nearest the front entrance command the most rent. Menashe makes money two ways, from rent and from charging a percentage of sales.

The ideal shopper, the developer says, is a lunch-hour visitor who comes in for a panini and leaves with a baby gift from Silly Souls, a book from Booksmart, and sunglasses from Selima Optique—a day’s errands done. It’s easy to see how this might appeal to the average multitasking New Yorker. The tough sell is going to be directing traffic to the odd corners of the place, of which there are many. Shopping on the upper floors requires a serious stair-climbing commitment. (There are no elevators.)

Another reason to believe the new Limelight can succeed is that it gives consumers a reason other than shopping to come inside. “One of the primary lessons we learned from the recession is that you have to transition from being a landlord to being a ‘placemaker,’ ” says Paco Underhill, CEO of the retail consulting group Envirosell. In other words, create an enticing visual environment, provide some high-density people-watching, and throw in free entertainment. To that end, Menashe intends to hire roving magicians and opera singers (yep, opera singers) on busy weekends.

Even before the marketplace opens, Menashe is making plans to roll out mixed-use Limelights all over the country. They won’t be in abandoned churches necessarily, but in similarly down-on-their-luck spots that offer customers an unusual shopping experience and store owners heavy foot traffic and a bargain rent. “The Limelight, no one knew what to do with it,” Menashe says. “Now we’ve got a 30-year lease.”