Six days before the Republican convention, the GOP — already with a woman problem on its hands — is endeavoring to gain its balance after one of its own, a Missouri congressman named Todd Akin, made his ignorance regarding the way babies are made, as well as a medieval blame-the-victim perspective on sexual violence, the talk of Twitter. But even if Akin had not made himself the gender-wars, culture-war story of the moment, the party’s retrograde attitude toward the role of women in the world, and in marriage, would find center stage in the persons (or personas) of Ann Romney and Janna Ryan.

Half of today’s law students are women and nearly a quarter of married women outearn their husbands, but Republican operatives want you to think Ann Romney stands for a different kind of achievement — the mid-century domestic martyr. “Gracious” and “soft-spoken” are adjectives used to describe her. She is “always in good humor.” Similarly, Janna Ryan is “quiet, gracious, and comfortable with being in the background.” She is “so supportive,” of her husband, friends say. She is “Paul’s rock.” Appearance matters in politics, and both women are so blond and so glossy (and yet, unlike Calista Gingrich, so warm and “natural” looking — another favorite descriptor), they might have stepped out of the pages of Town and Country magazine or the J. Crew catalog.

Both are stay-at-home moms — they can afford to be — and the party likes it that way. Surrogates constantly stress these political wives’ devotion not just to husband (and husband’s career) but to home, children, and hearth. “Janna is a wonderful parent to their children and will be Paul’s strongest supporter on the campaign trail,” her cousin and fellow Oklahoman, the former Democratic Senator David Boren, told the Daily Beast. And when a Democratic operative named Hilary Rosen tried earlier this year to pierce Ann Romney’s armor of perfect motherhood, declaring that she “hasn’t worked a day in her life,” she lost the battle. Stay-at-home motherhood is still so sacrosanct an occupation that Rosen was immediately and widely rebuked, including by the President himself. (Her point — that Mrs. Romney couldn’t possibly understand or feel the pain of women who have to raise children and make it to work on time — was lost in the kerfuffle.)

Janna Ryan did, formerly, have a career. She went to Wellesley, then to law school, then worked as a lobbyist for Price Waterhouse Cooper. She met Ryan at the ripe old age of 31, and only then moved from Washington, D.C. to Janesville, Wisconsin, Ryan’s hometown, to a big house with eight bathrooms. The Ryans “wanted to make sure their kids had the experience Janna and Paul did,” Paul’s Wisconsin colleague Dave Craig said, “that they have an upbringing with a backyard, be able to kick a ball around, throw a ball around in the backyard.” No judgment here — these decisions are hard— but it does make you wonder whether “quiet, gracious, and comfortable being the background” are really accurate descriptors. Janna sounds like she can be a dynamo.

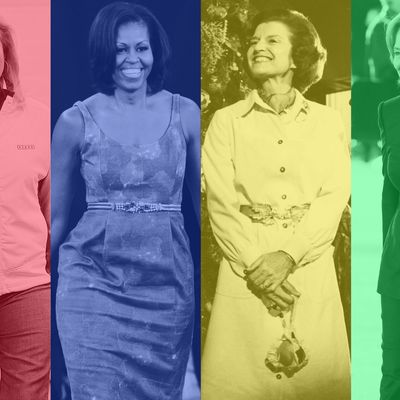

The lives of First and Second ladies rarely reflect the real lives of American women, and in retrospect many have said how hard that disconnect can be. (Betty Ford was eloquent on this point. So was Kitty Dukakis. And Hillary Clinton visibly flailed at trying to mold herself into someone else’s idea of what she should be.) Nevertheless, the Republicans continue to be so bent on making their political wives conform to some 60-year-old ideal that the campaign machinery has smoothed away all the bumps and cracks of actual life. Did Janna experience any adjustment pains when she moved from D.C., the center of government power, to small-town Wisconson where she had her babies? Has Ann ever dreamed of emulating Melinda Gates and using her considerable wealth on behalf of the needy? (She has Multiple Sclerosis: Her illness is a defining force in the family. Still one wonders whether she’s assumed her role as contended wife and mother without mixed feelings at all.)

Misses Romney and Ryan both subscribe to faiths — Mormonism for Romney and Catholicism for Ryan — that put men above women (no matter what their authorities say). In Mormonism, the father is the spiritual leader of the household and the last word; in Catholicism, of course, religiously motivated women can’t become priests — only nuns, and then targets for disciplinary action and disapproval. Perhaps long exposure to this kind of male dominance (within a broader culture that constantly questions it) has allowed these political wives to stay silent on matters that affect them. It is impossible to imagine a woman, no matter how supportive, who is able to distinguish between rape and “forcible” rape (the phraseology in Ryan’s anti-abortion “personhood” bill, which he sponsored with the now politically radioactive Todd Akin).

On the blue team, the marriages look just as scripted, and just as glossy, but messier somehow. Michelle Obama, who until 2008 worked as the director of community affairs for the University of Chicago hospital system, only resigned when her husband launched on the general election phase of his campaign. Once he won, she actually considered staying with her girls in Chicago while her husband started his job in the White House, according to Jodi Kantor’s book The Obamas. Neither she (nor her husband) has any problem talking about how juggling work and the responsibilities of family is hard. “We all know that when you take steps to make life easier for working parents, it’s a win for everyone,” she said at the National Science Foundation last year when it unveiled incentives for helping women have careers in science. “Workplace flexibility policies can increase worker productivity.”

Jill Biden, for her part, continues to teach English at a community college and insists on using the “Dr.” honorific — a pretense, but an explicit show of the importance she places on her role outside the home. “I wanted my own money, my own identity, my own career,” she said in 2007.

The differences become more striking when you look at the numbers. Republicans, the data says, get divorced more than Democrats do. Three of the states with the highest divorce rate — Arkansas, Wyoming, Idaho — are red, and a fourth, Nevada, went to Obama in 2008 but has a powerful Republican tradition and is a tossup now. The states with the lowest divorce rates — Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania, Iowa, New York — are traditionally blue. A controversial 2008 poll showed that born-again Christians (who skew heavily Republican) had among the highest divorce rates in the country, whereas atheists and agnostics (who tend to be Democrats) had the lowest.

Maybe there’s a lesson in here. Longevity in marriage is perhaps a matter of not insisting that everything’s perfect, of treating the institution itself as idealized and invioble but admitting that it’s not — of recalibrating and experiencing crisis and disappointment and well as pleasure and success and then going ahead and sticking with it anyway.